Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Royal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

Still more characteristic is the description given by the same pen of Knox's public appearances. It was young Melville's greatest privilege, the best of all the benefits he received during that year, to hear "that maist notable prophet and apostle of our nation preach."

"I had my pen and my little book and took away such things as I could comprehend. In the opening of his text he was moderate for the space of half an hour, but when he entered to application he made me so to grew and tremble that I could not hold a pen to write. In St. Andrews he was very weak. I saw him every day of his doctrine go hulie and fear (hooley and fairly, gently and with caution), with a furring of martins about his neck, a staff in the ane hand, and gude godlie Richart Ballenden holding up the other oxter, from the Abbey to the Parish Kirk; and by the same Richart and another servant lifted up to the pulpit, where he behoved to lean at his first entry; but ere he had dome his sermon, he was sae active and vigorous that he was like to ding the pulpit in blads and flie out of it."

Melville says much, as indeed most of the narratives of the time do, of Knox's prophecies, especially in respect to the Castle of Edinburgh, which he said would run like a sand-glass—a prediction supposed to be fulfilled by a shower of sand pouring from some portion of the rock; and its Captain, Kirkaldy, who was to escape over the walls, but to be taken and to hang against the sun. All of which things, and many more, occurred precisely as the seer said, after his death, striking great awe to the hearts of those to whom the predictions were made. The special prophecy in respect to Grange was softened by the announcement that "God assures me there is mercy for his soul." And it is at once pathetic and impressive to read of the consolation which this assurance gave to the chivalrous Kirkaldy on the verge of the scaffold; and the awe-inspiring spectacle presented to the believers, who after his execution saw his body slowly turn and hang against the western sun, as it poured over the Churchyard of St. Giles's, "west, about off the northward neuk of the steeple." But this was after the prophet himself had passed into the unseen.

Knox returned to Edinburgh in 1572, in August, the horrors of the struggle between the Queen's party and the King's, as it was called, or Regent's, being for the moment quieted, and the banished citizens returning, although no permanent pacification had yet taken place. He had but a few months remaining of life, and was very weary of the long struggle and longing for rest. "Weary of the world, and daily looking for the resolution of this my earthly tabernacle," he says. And in his last publication dated from St. Andrews, whither the printer Lekprevik had followed him, he heartily salutes and takes good-night of all the faithful, earnestly desiring the assistance of their prayers, "that without any notable scandal to the evangel of Jesus Christ I may end my battle: for," he adds, "as the world is weary of me, so am I of it." He lived long enough to welcome his successor in St. Giles's, to whom, to hasten his arrival, he wrote the following touching letter, one of the last compositions of his life:—

"All worldlie strength, yea even in things spiritual, decayes, and yet shall never the work of God decay. Belovit brother, seeing that God of His mercy, far above my expectation, has callit me over again to Edinburgh, and yet that I feel nature so decayed, and daylie to decay, that I look not for a long continuance of my battle, I would gladly ance discharge my conscience into your bosom, and into the bosom of others in whom I think the fear of God remains. Gif I had the abilitie of bodie, I suld not have put you to the pain to the whilk I now requyre you, that is, ance to visit me that we may confer together on heavenly things; for into earth there is no stability except the Kirk of Jesus Christ, ever fighting under the cross; to whose myghtie protection I heartilie commit you. Of Edinburgh the VII. of September 1572.

Jhone Knox."Haist lest ye come too lait."

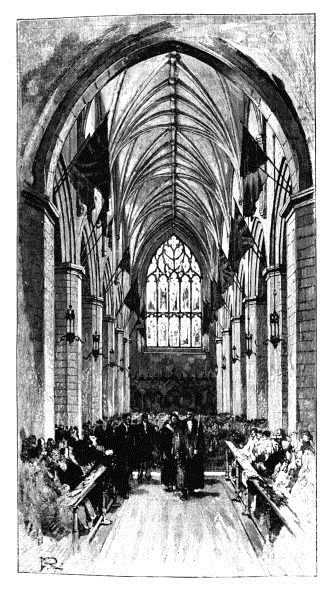

He lived to induct this successor, and to hear the terrible news of that massacre in France, which horrified all Christendom, but was of signal good to Scotland by procuring the almost instantaneous collapse of the party which fought for the Queen, and held the restoration of Roman Catholic worship to be still possible. That hope died out with the first sound of the terrible news which proved so abundantly Knox's old assertion that in the hands of the Papists there was no safety for his life, or the life of any who believed with him. Almost, however, before this grain of good in the midst of so much evil became apparent the prophet had taken his departure from this world. After the simple ceremonial at which he had officiated, of his successor's installation, John Knox returned home in the light of the brief November day, as Melville had seen him, supported by the arm of his faithful servant. The crowd which had filled St. Giles's hurrying out before him lined the street, and watched the old man as he crept along down the hill to his house, with many a shaken head and many a murmured blessing. In this last scene all were unanimous; there was no one to cast a gibe or an unkindly look upon that slow aged progress from the scene of his greatest labours to the death-bed which awaited him. When the spectators saw him disappear within his own door, they all knew that it was for the last time. He lay for about a fortnight dying, seeing everybody, leaving a charge with one, a prophecy with another, with a certain dignified consciousness that his death should not be merely as other men's, and that to show the reverential company of friends who went and came how to die was the one part of his mission which had yet to be accomplished. He ended his career on the 24th November 1572, having thus held a sort of court of death in his chamber and said everything he had to say—dying a teacher and prophet to men, as he had lived.

INTERIOR OF ST. GILES'S

No man has been more splendidly applauded, and none more bitterly dispraised. It is in one sense the misfortune of our age that it is little able to do either. If steadfast adherence to what he thought the perfect way, if the most earnest purpose, the most unwearying labour, the profoundest devotion to his God and his country are enough to constitute greatness, John Knox is great. He was at the same time a man all faults, bristling with prejudices, violent in speech, often merciless in judgment, narrow, dogmatic, fiercely intolerant. He was incapable of that crowning grace of the imagination and heart which enables a man to put himself in another's place and do as he would be done by. But even this we must take with a qualification; for Knox would no doubt have replied to such an objection that had he been a miserable idolater, as he considered the upholders of the mass to be, he could not but have been grateful to any man who had dragged him by whatever means from that superstition. He was so strong in the certainty of being right that he was incapable even of considering the possibility that he might be wrong. And there was in him none of those reluctances to give pain, none of those softening expedients of charity which veil such a harsh conviction and make men hesitate to condemn. He knew not what hesitation was, and scorned a compromise as if it had been a lie, nor would he suffer that others should do what was impossible to himself. His determination to have his own way was indeed justified by the conviction that it was the way of God, but his incapability of waiting or having patience, or considering the wishes and convictions of others, or contenting himself with a gradual advance and progression, have no such excuse.

These were, however, of the very essence of his character. A perfectly dauntless nature fearing nothing, the self-confidence of an inspired prophet, the high tyrannical impulse of a swift and fiery genius impatient of lesser spirits, were all in him, making of him the imperative, absolute, arrogant autocrat he was; but yet no higher ambition, no more noble purpose, ever inspired a man. He desired for his countrymen that they should be a chosen people like those of old whom God had selected to receive His revelation; his ambition was to make Scotland the most pure, the most godlike, of all countries of the earth. In many things he was intolerable, in some he was wrong and self-deceived. He was too eager, too restless, too intent upon doing everything, forcing the wheels of the great universe and clutching at his aim whatever conditions of nature might oppose—to be wholly heroic. Yet there are none of the smoother or even more lovable figures of history whom it would be less possible to strike from off the list of heroes. The impression which he left upon the religion and character of Scotland remains to this day; and if we think, as many have done during all these ages, that that development of national life is the highest that could be aimed at, John Knox was one of the greatest of men. But if he transmitted many great qualities to his country, he also transmitted the defects of these qualities. He cut Scotland adrift in many respects from the community of Christendom. He cut her off from her ancestors and from those hallowing traditions of many ages which are the inheritance of the universal Church. He taught her to exult in that disruption, not to regret it; and he left an almost ineradicable conviction of self-superiority to a world lying in wickedness, in the innermost heart of the nation. It is a wonderful testimony to a man that he should have thus been able to imprint his own characteristics upon his race: and no doubt it is because he was himself of the very quintessence of its national character to start with, that he has maintained this prodigious power through these three hundred years.

KNOX'S PULPIT. In the Antiquarian Society's Museum, Edinburgh.

He lies, it is thought, if not within the walls of St. Giles's under the flags between the Cathedral and the Parliament House, with all the busy life of modern Edinburgh, the feet of generations of men treading out the hours and years over his head; a more appropriate bed for him than green mound or marble monument. That stony square is consecrated ground blessed near a thousand years ago by ancient priests who cared little more for Rome than do their modern successors now. But little heeded Knox for priestly blessing or consecrated soil. "The earth is the Lord's and the fulness thereof" was the only consecration of which he thought.

CHAPTER IV

THE SCHOLAR OF THE REFORMATION

The age of Mary Stewart is in many ways the climax of Scottish national history, as well as one of the most interesting and exciting chapters in the history of the world. The Stewarts of Scotland had been up to this point a native race entirely Scots in training as in birth, and bent above all things upon the progress and consolidation of their own ancient kingdom, the poor but proud; a speck all but lost in the distance of the seas, yet known all over Christendom wherever errant squires or chivalrous pretensions were known. But the new sovereign of Scotland was one whose heart and pride were elsewhere, whose favourite ambitions were directed beyond the limits of that ancient kingdom with which she had none of the associations of youth, and to which she came a stranger from another Court far more dazzling and splendid, with hopes and prospects incapable of being concentrated within the boundary of the Tweed. There is no indication that the much-contested history of Mary Stewart has lost any of its interest during the progress of the intermediate centuries; on the contrary, some of its questions are almost more hotly contested now than they were at the moment when they arose. Her chivalrous defenders are more bold than once they were, and though the tone of her assailants is subdued, it is from a natural softening of sentiment towards the past, and still more from the fashion of our time, which finds an absorbing interest in the manifestations of individual character and the discussion of individual motives, rather than from any change of opinion. I do not venture to enter into that long-continued conflict, or to attempt to decide for the hundredth time whether a woman so gifted and unfortunate was more or less guilty. Both parties have gone, and still go, too far in that discussion; and Mary would not have thanked (I imagine) those partisans who would prove her innocence at the cost of all those vigorous and splendid qualities which made her remarkable. She could scarcely be at once an unoffending victim and one of the ablest women of her time.

As this is the most interesting of all the epochs of Scottish history—and that not for Mary's sake alone, but for the wonderful conflict going on apart from her, and in which her tragic career is but an episode—so it is the most exciting and picturesque period in the records of Edinburgh, which was then in its fullest splendour of architectural beauty and social life; its noble streets more crowded, more gay, more tumultuous and tragical; its inhabitants more characteristic and individual; the scenes taking place within it more dramatic and exciting than at any other part of its history. Fine foreign ambassadors, grave English diplomates trained in the school of the great Cecil, and bound to the subtle and tortuous policy of the powerful Elizabeth; besides a new unusual crowd of lighter import but not less difficult governance, the foreign artists, musicians, courtiers of all kinds, who hung about the palace, had come in to add a hundred complicating interests and pursuits to the simpler if fiercer contentions of feudal lords and protesting citizens: not to speak of the greatest change of all, the substitution for the ambitious Churchman of old, with a coat of mail under his rochet, of the absolute and impracticable preacher who gave no dispensations or indulgences, and permitted no compromise. All these new elements, complicated by the tremendous question of the English succession, and the introduction of many problems of foreign politics into a crisis bristling with difficulties of its own, made the epoch extraordinary; while the very streets were continually filled by exciting spectacles, by processions, by sudden fights and deadly struggles, by pageants and splendours, one succeeding another, in which the whole population had their share. The decree of the town council that "lang weapons," spears, lances, and Jedburgh axes, should be provided in every shop—so that when the town bell rang every man might be ready to throw down his tools or his merchandise and grip the ready weapon—affords the most striking suggestion of those sudden tumults which might rise in a moment, and which were too common to demand any special record, but kept the town in perpetual agitation and excitement—an agitation, it is true, by no means peculiar to Edinburgh. No painter has ever done justice to the scene which must have been common as the day, when the beautiful young Queen, so little accustomed to the restraints and comparative poverty of her northern kingdom, and able to surround herself with the splendour she loved out of her French dowry, rode out in all her bravery up the Canongate, where every outside stair and high window would be crowded with spectators, and through the turreted and battlemented gate to the grim fortress on the crown of the hill, making everything splendid with the glitter of her cortege and her own smiles and unrivalled charm. Sadder spectacles that same beautiful Queen provided too—miserable journeys up and down from the unhappy palace, sometimes through a stern suppressed tumult of hostile faces, sometimes stealthily under cover of night which alone could protect her. Everything in Edinburgh is associated more or less with Mary's name. There is scarcely an old house existing, with any authentic traces of antiquity, in which she is not reported to have taken refuge in her trouble or visited in her pleasure. The more vulgar enthusiasts of the causeways are content to abolish all the other associations of old Edinburgh for Mary's name.

But I will not attempt to revive those pageants either of joy or sorrow. There are other recollections which may be evoked with less historical responsibility and at least a little more freshness and novelty. No figure can be introduced out of that age who has not some connection one way or other with the Queen; and the great scholar, whose reputation has remained unique in Scotland, had some share in her earlier and happier life, as well as a link, supposed of treachery, with her later career. George Buchanan was the Queen's reader and master in her studies when all was well with her. He is considered by some of her defenders to be the forger of the wonderful letters which, if true, are the most undeniable proof of her guilt. But these things were but incidents in his career, and he is in himself one of the most illustrious and memorable figures among the throngs that surrounded her in that brief period of sovereignty which has taken more hold of the imagination of Scotland, and indeed of the world, than many a longer and, in point of fact, more important reign.

It is difficult to understand how it is that in later days, and when established peace and tranquillity of living might have been supposed to give greater encouragement to study, accurate and fine scholarship should have ceased to be prized or cultivated in Scotland. Perhaps, however, the very advantages upon which we have plumed ourselves so long, the general diffusion of education and higher standard of knowledge, is one of the causes of this failure—not only the poverty of Scotch universities and want of endowments, but the broader and simpler scale on which our educational systems were founded, and which have made it more important to train men for the practical uses of teaching than permit to them the waywardness and independence of a scholar. These results show the "défauts de nos qualités," though we are not very willing to admit the fact. But in the earlier centuries no such reproach rested upon us. Although perhaps, then as now, the Scotch intelligence had a special leaning towards philosophy, there was still many a learned Scot whose reputation was in all the universities, whose Latinity was unexceptionable, and his erudition immense, and to whom verses were addressed and books dedicated in every centre of letters. One of the most distinguished of these scholars was George Buchanan, and there could be no better type of the man of letters of his time, in whom the liberality of the cosmopolitan was united with the exclusiveness of the member of a very strait and limited caste. He had his correspondents in all the cities of the Continent, and at home his closest associates were among the highest in his own land. Yet he was the son of a very poor man, born almost a peasant and dying nearly as poor as he was born. From wandering scholar and pedagogue he became the preceptor of a King and the associate of princes; but he was not less independent, and he was scarcely more rich in the one position than the other. His pride was not in the high consultations he shared or the national movements in which he had his part, but in his fine Latinity and the elegant turn of those classical lines which all his learned compeers admired and applauded. The part that he played in history has been made to look odious by skilled critics; and the great book in which he recorded the deeds of his contemporaries and predecessors has been assailed violently and bitterly as prejudiced, partial, and untrue. But nobody has been able to attack his Latin or impair the renown of his scholarship; and perhaps had he himself chosen the foundation on which to build his fame, this is what he would have preferred above all. History may come and politics go, and the principles of both may change with the generations, but Latin verse goes on for ever: no false ingenuity of criticism can pick holes in the deathless structure of an art with which living principles have had nothing to do for a thousand years and more.

Buchanan was born in a farmhouse, "a lowly cottage thatched with straw," in the year 1506, in Killearn in the county of Stirling; but not without gentle blood in his veins, the gentility so much prized in Scotland, which makes a traceable descent even from the roughest of country lairds a matter of distinction. His mother was a Heriot, and one wonders whether there might not be some connection between the great scholar and the worthy goldsmith of the next generation, who did so much for the boys of Edinburgh. Buchanan's best and most trustworthy biographer, Dr. Irving,5 pictures to his readers the sturdy young rustic trudging two miles in all weathers to the parish school, with his "piece" in his pocket, and already the sonorous harmonies of the great classic tongues beginning to sound in his ears—a familiar picture which so many country lads born to a more modest fame have emulated. In the parish school of Killearn, in that ancient far-away Scotland before the Reformation, which it is hard to realise, so different must it have been from the characteristic Scotch school of all our traditions, the foundations of Buchanan's great scholarship and power were laid. His father died while he was still a mere child, and the future man of letters had plenty of rough rustic work, helping his mother about the farm on the holidays, which must have been more frequent while all the saints of the calendar were still honoured. Trees of his planting, his biographer says, writing in the beginning of this century, still grow upon the banks of the little stream which runs by the beautiful ruins of Dunblane, and which watered his mother's fields. When he had reached the age of fourteen an uncle Heriot seeing his aptitude for study sent him off, it would seem alone, in all his rusticity and homeliness, to Paris—a curious sign of the close connection between Scotland and France—where he carried on his studies or, a phrase more appropriate to his age, learned his lessons amid the throngs of the French schools. Before he was sixteen, however, his uncle died, leaving him desolate and unprovided for amongst strangers; and the boy had to make his way home as best he could, half begging, half working his passage, stopping perhaps here and there to help a schoolboy or to write a letter for the unlearned, and earning a bed and a meal as poor scholars were used to do. He remained a year in his mother's house, but probably was no longer wanted for the uses of the farm, since his next move was to the wars. He himself informs us in the sketch of his life which he wrote in his old age that he was "moved with a desire to study military matters," a desire by no means unusual at seventeen. These were the days when the fantastic French Albany was at the head of affairs in Scotland, during the childhood of James V, and the country was in great disorder, torn with private quarrels and dissensions. It is evident that, the kind uncle being dead and affairs in general so little propitious, there would be little chance in the resources of the farm of securing further university training for the boy who had his own way to make somehow in the world; and perhaps his experience of Paris and possession of the French language (no inconsiderable advantage when there were so many French adventurers and hangers on about the Court) might be expected to give him chances of promotion; while his service perhaps exempted an elder brother, of more use than he upon the farm, from needful service, when his feudal lord called out his men on the summons of the Regent.

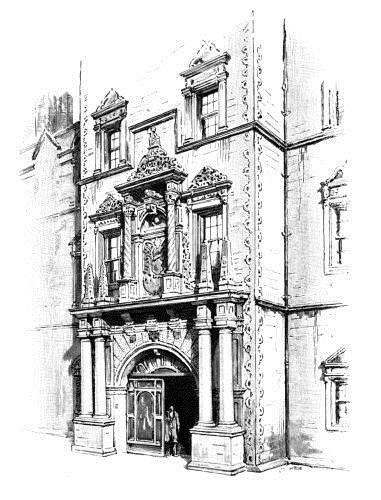

NORTH DOORWAY, HERIOT'S HOSPITAL

George Buchanan accordingly followed the Laird's flag upon one of the wildest and most fruitless of Albany's expeditions to the Border, for the siege of Wark. The great Border stronghold, the size and wonderful proportions of which astonished the Scots army, stands forth again, clear as when it first struck his boyish imagination, in the description which Buchanan gives of it nearly half a century later in his history of that time—where the reader can still see the discomfited army with its distracted captains and councils, and futile leader, straggling back through the deep snow, each gloomy band finding its way as best it could to its own district. Buchanan would seem to have had enough of fighting; and perhaps he had succeeded in proving to his relatives that neither arms nor agriculture were his vocation; for we next find him on his way to St. Andrews, "to hear John Major who was then teaching dialectics or rather sophistry." Here he would seem to have studied for two years; taking his degree in 1525 at the age of nineteen. After this he followed Major to France, whether for love of his master, or with the idea that Major's interest as a doctor of the Sorbonne might help him to find employment in Paris, we are not told. One of the many stories to his prejudice which were current in his after-career describes Buchanan as dependent on Major and ungrateful to him, repaying with a cruel epigram the kindness shown him. But there seems absolutely no foundation for this accusation which was probably suggested to after-detractors anxious for evidence that ingratitude, as one of them says, "was the great and unpardonable blemish of his life"—by the epigram in question, in which he distinguishes his professor as "solo cognomine Major." It might very well be, however, that Buchanan expected a kind recommendation from his St. Andrews master, such as the habit of the kindly Scots was apt to give, and some help perhaps in procuring employment, and that the failure of any aid of this description betrayed the youth into the national tendency to harshness of speech and the bitter jeer at one who was great only in his name.