Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Royal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

He was ordered to withdraw after this, and retired proud and silent to the ante-room where he had immediate proof what it was to lose the royal favour. Hitherto he had been, it is clear, a not unwelcome visitor: to Mary an original, something new in prickly opposition and eloquence, holding head against all her seductions, yet haply, at Lochleven at least, not altogether unmoved by them, and always interesting to her quick wit and intelligence; and Maister John had many friends among the courtiers. But now while he waited the Queen's pleasure, not knowing perhaps if she might not send him to the Castle or the Tolbooth in her wrath, all his fine acquaintances forsook him. He stood, "the said John," for an hour in that bustling ante-room, "as one whom men had never seen," only Lord Ochiltree who had come to Holyrood with him, and whose daughter he was about to marry, giving any sign of acquaintance to the disgraced preacher. And Knox was human: he loved the cold shade as little as any man, and the impertinences of all those butterfly courtiers moved him as such a man ought not to have been moved. He burst out suddenly upon the ladies who sat and whispered and tittered among themselves (no doubt) at his discomfiture. He would not have us think even then that his mind was disturbed; he merely said—

"Oh fayr Ladies, how pleasant were this life of yours if it should ever abide, and then in the end that we might pass to heaven with all this gay gear! But fie upon that Knave Death that will come whether we will or not. And when he has laid on his arrest the foul worms will be busy with this flesh be it never so fayre and so tender, and the silly soul, I fear, shall be so feeble that it can neither carry with it gold garnissing, tarjetting, pearls, nor precious stones!"

Knox was never called to the royal presence more, nor did Mary ever forgive him the exhibition of feminine weakness into which his severity had driven her. It was intolerable, no doubt, to her pride to have been betrayed into those tears, to have seen through them the same immovable countenance which had yielded to none of her arguments and cared nothing for her anger, and to have him finally compare her to his own boys whom his own hands corrected—the blubbering of schoolboys to the tears of a queen! There is perhaps always a mixture of the tragi-comic in every such scene, and this humiliating comparison, obtusely intended as a sort of blundering apology, but which brought the Queen's exasperation and mortification to a climax, and Knox's bitter assault upon the ladies in their fine dresses outside, give a humiliating poignancy to the exasperated feeling on both sides such as delights a cynic. It was the end of all personal encounter between the Queen and the preacher. She did not forgive him, and did her best to punish: but in their last and only subsequent meeting, Knox once more had the better of his royal adversary.

He had never been during all his career in such stormy waters as now threatened to overwhelm him. Hitherto his bold proceedings had been justified by the support of the first men in the kingdom. The Lords of the Congregation, as well as that Congregation itself, the statesmen and "natural counsellors," as they call themselves, of Scotland, had been at his back: but now one by one they had fallen away. The Lord James, now called Murray, the greatest of all both in influence and character, had been the last to leave his side. The preachers, the great assembly that filled St. Giles's almost daily, the irreconcilables with whom it was a crime to temporise, and who would have all things settled their own way, formed, it is true, a large though much agitated backing; but the solid force of men who knew the world better than those absolute spirits, had for the moment abandoned the impracticable prophet, and the party of the Queen was eagerly on the watch to find some opportunity of crushing him if possible. It was not long before this occurred. While Mary was absent on one of those journeys through the kingdom which had been the constant habit of Scottish monarchs, the usual mass was celebrated in the Chapel of Holyrood, the priests who officiated there evidently feeling themselves authorised to continue their usual service even in the Queen's absence, for whose sake alone it was tolerated. But they were interrupted by "a zealous brother," and some little tumult rose, just of importance enough to justify the seizure of two offenders, who were bound under sureties to "underlie the law" at a given date, within three weeks of the offence. In the excited state of feeling which existed in the town this arrest was magnified into something serious, and "the brethren," consulting over the matter with perhaps involuntary exaggeration, as if the two rioters were in danger of their lives, concluded that Knox should write a circular letter to the Congregation at a distance, as had been done with such effect in the early days under the Queen Regent, bidding them assemble in Edinburgh upon the day fixed for the trial. A copy of this letter was carried to the Court then at Stirling and afforded the very occasion required. Murray returned in haste from the north, and all the nobility were called to Edinburgh to inquire into this bold semi-royal summons issued to the Queen's lieges without her authority and in resistance to her will. "The Queen was not a little rejoiced," says Knox, "for she thought once to be revenged of that her great enemy." And it was evident that Mary did look forward to the satisfaction of crushing this arrogant priest and achieving a final triumph over the man whom she could neither awe nor charm out of his own determined way.

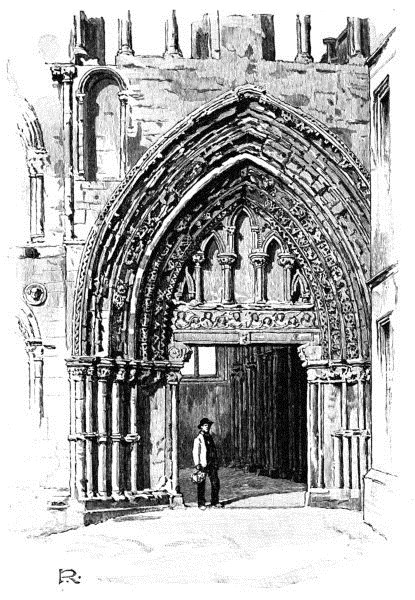

WEST DOORWAY, HOLYROOD CHAPEL

The commotion produced by these proceedings was unexampled. One after another of the men who had by Knox's side led the entire movement of the Reformation and to whom he had been spokesman, secretary, and counsellor, came with grave looks and anxious urgency to do what they could to procure his submission. The Master of Maxwell, hitherto his great friend, but who now broke off from him entirely, was the first to appear; Then Speirs of Condie (whom he convinced), then Murray and Lethington with whom he held one of those long arguments which were of frequent recurrence, and which are always highly dramatic—the dour preacher holding his own like a stone wall before all the assaults, light, brilliant, and varied, of the accomplished secretary, whose smile of contempt at the unconquerable personage before him and his "devout imaginations" is often mingled with that same exasperation which drove Mary to the womanish refuge of tears. But no one could move him. And at last the day, or rather night, of the trial came.

It was in December, the darkest moment of the year, between six and seven in the evening, when the Lords assembled at Holyrood, and the formidable culprit was introduced to their presence. The rumour had spread in the town that Knox was to be put on his trial, and the whole Congregation came with him down the Canongate, filling the court of Holyrood with a dark surging mass of men, who crowded the very stairs towards the room in which the council was held. The lords were "talking ane with another" in the preliminary moment before the council was formed, when Knox entered the room. They were then told to take their places, headed on one side by "the Duke" Chatelherault, and on the other by Argyle. Murray, Glencairn, Ruthven, the Earl Marischal, Knox's tried companions in arms, who had stood with him through many a dark day, took their seats with averted looks, his judges now, and judges offended, repulsed, their old sympathies aggravating the breach. Then came the Queen "with no little worldly pomp," and took the chair between those two rows of troubled counsellors, Lethington at one side, Maxwell at the other. She gave an angry laugh as she took her place. "Wat ye4 whereat I laugh?" she said (or is reported to have said) to one of these intimate supporters. "Yon man gart me greit, and grat never tear himself: I will see if I can gar him greit."

The proceedings being opened, Knox's letter was read. It was not a conciliatory letter, being in reality a call if not to arms yet to that intervention of an army of resolute men which had overawed the authorities again and again in earlier times. It contained the usual vehement statements about that crime of saying mass which, or even to permit it, was the most desperate of public offences in Knox's eyes: and there is little doubt that it exaggerated the danger of the crisis, and contained at least one misleading statement as to matters of which there was no proof. When it was read a moment of silence ensued, and then Lethington spoke:—

"Maister Knox, are ye not sorry from your heart, and do ye not repent that sic ane letter has passed your pen, and from you is come to the knowledge of others?"

John Knox answered, "My Lord Secretaire, before I repent I must be taught my offence."

"Offence!" said Lethington; "if there were no more but the convocation of the Queen's lieges the offence cannot be denied."

"Remember yourself, my lord," said the other, "there is a difference between ane lawful convocation and ane unlawful. If I have been guilty in this, I have often offended since I came last in Scotland; for what convocation of the brethren has ever been to this day with which my pen served not? Before this no man laid it to my charge as a crime."

"Then was then," said Lethington, "and now is now. We have no need of such convocations as sometime we have had."

John Knox answered, "The time that has been is even now before my eyes; for I see the poor flock in no less danger now than it has been at any time before, except that the Devil has gotten a vissoure upon his face. Before he came in with his own face discovered by open tyranny, seeking the destruction of all that has refused idolatrie; and then I think ye will confess the brethren lawfully assembled themselves for defence of their lives. And now the Devil comes under the cloke of justice to do that which God would not suffer him to do by strength."

"What is this?" said the Queen. "Methinks ye trifle with him. Who gave him authoritie to make convocation of my lieges? Is not that treason?"

"Na, Madam," said the Lord Ruthven, "for he makes convocation of the people to hear prayer and sermon almost daily, and whatever your Grace or others will think thereof, we think it no treason."

"Hold your peace," said the Queen, "and let him answer for himself."

"I began, Madam," said John Knox, "to reason with the Secretare, whom I take to be ane far better dialectician than your Grace is, that all convocations are not unlawful; and now my Lord Ruthven has given the instance, which, if your Grace will deny, I shall address me for the proof."

"I will say nothing," said the Queen, "against your religion, nor against your convening to your sermons. But what authority have ye to convocate my subjects when you will, without my commandment?"

"I have no pleasure," said John Knox, "to decline from the former purpose. And yet, Madam, to satisfy your Grace's two questions I answer, that at my will I never convened four persons in Scotland; but at the order that the brethren has appointed I have given divers advertisements and great multitudes have assembled thereupon. And if your Grace complain that this was done without your Grace's commandment, I answer, so has all that God has blessed within this Realm, from the beginning of this action. And therefore, Madam, I must be convicted by ane just law, that I have done against the duties of God's messenger in writing this letter, before that either I be sorry or yet repent for the doing of it, as my Lord Secretare would persuade me; for what I have done I have done at the commandment of the general Kirk of this realm; and therefore I think I have done no wrong."

This detailed report is in the form of an addendum to Knox's original manuscript, written hurriedly as if from dictation, as though in the leisure of his later days the Reformer had thought it well to enrich the story with so lifelike and well-remembered a scene. Nothing could be more animated than the introduction of the different personages of this grave tribunal. The long argument with Lethington which might have been carried on indefinitely till now, the hasty interruption of the Queen, not disposed to be troubled with metaphysics, to bring it back to the practical question, the quibble of Ruthven of which Knox makes use, but only in passing, are all as real as though we had been present at the council. The Queen, with feminine persistence holding to her question, is the only one of the assembly who has any heart to the inquiry. The heat of a woman and a monarch personally offended is in all she says, as well as a keen practical power of keeping to her point. It is she who refers to the corpus delicti, carrying the question out of mere vague discussion distinctly to the act complained of. Knox had said in his letter that the prosecution of the men who had interrupted the service at Holyrood was the opening of a door "to execute cruelty upon a greater multitude." "So," said the Queen, "what say ye to that?" She received in full front the tremendous charge which followed:—

"While many doubit what the said John should answer he said to the Queen, 'Is it lawful for me, Madam, to answer for myself? Or shall I be dampned before I be heard?'

'Say what ye can,' said she, 'for I think ye have enough ado.'

'I will first then desire this of your Grace, Madam, and of this maist honourable audience, whether if your Grace knows not, that the obstinate Papists are deadly enemies to all such as profess the evangel of Jesus Christ, and that they most earnestly desire the extermination of them and of the true doctrine that is taught in this realm?'

The Queen held her peace; but all the lords with common voice said, 'God forbid that either the lives of the faithful or yet the staying of the doctrine stood in the power of the Papists; for just experience tells us what cruelty lies in their hearts.'"

This sudden turn of opinion, coming from her council itself, and which already constituted a startling verdict against her, Mary seems to have sustained with the splendid courage and self-control which she displayed on great occasions: no tear now, no outburst of impatience. She did not even attempt to deny the tremendous indictment, but allowed Knox to resume his pleading. And when she spoke again it was with a complete change of subject. Apparently her quick intelligence perceived that after that remarkable incident the less said to recall the first object of the council the better. She went back to her original grievance, accusing Knox though he spoke fair before my lords (which indeed it was a strain of forbearance to say) that he had caused her "to weep many salt tears" at their previous meeting. His reply has much homely dignity.

"Madam," he said, "because now the second time your Grace has branded me with that crime I must answer, lest for my silence I be holden guilty. If your Grace be ripely remembered, the Laird of Dun, yet living to testify the truth, was present at that time whereof your Grace complains. Your Grace accused me that I had irreverently handled you in the pulpit; that I denied. Ye said, what ado had I with your marriage? What was I that I should mell with such matters? I answered as touching nature I was ane worm of this earth, and ane subject of this Commonwealth, but as touching the office whereintil it has pleased God to place me, I was ane watchman both over the Realm, and over the Kirk of God gathered within the same, by reason whereof I was bound in conscience to blow the trumpet publicly as oft as ever I saw any upfall, any appearing danger either of the one or of the other. But so it was that ane certain bruit appeared that traffic of marriage was betwixt your Grace and the Spanish Ally; whereunto I said that if your nobilitie and your Estates did agree, unless that both you and your husband shall be so directly bound that neither of you might hurt this Commonwealth nor yet the poor Kirk of God within the same, that in that case I would pronounce that the consenters were troublers of this Commonwealth and enemies to God and to His promise planted within the same. At those words I grant your Grace stormed and burst forth into an unreasonable weeping. What mitigation the Laird of Dun would have made I suppose your Grace has not forgot. But while that nothing was able to stay your weeping I was compelled to say, I take God to witness that I never took pleasure to see any creature weep (yea, not my own children when my own hand bett them), meikle less can I rejoice to see your Grace make such regret. But seeing I have offered your Grace no such occasion, I must rather suffer your Grace to take your own pleasure than that I dare to conceal the truth and so betray both the Kirk of God and my Commonwealth. These were the most extreme words I said."

Having thus repeated his offence (even to the tears of the schoolboys) the Reformer's shrift was ended and he was told that he might return to his house "for that night." No doubt what he himself said is more clearly set forth than what others replied, but that he distinctly carried the honours of the discussion with him, and that his mien and bearing, as here depicted, are manly, grave, and dignified as could be desired, will not be denied by any reasonable reader. That they impressed the council in the same way is equally evident; that council was composed of his ancient companions in arms, the comrades of many an anxious day and of many a triumphant moment. That he had offended and broken with several of them would not affect the consideration that to condemn John Knox was not a light matter; that through all the hours of that winter evening half Edinburgh had been filling the Court of Holyrood and keeping up a murmur of anxiety at its gates; and that it was a dangerous crowd to whom my lords would have to give account if a hair of his head was touched. The conclusion apparently came with the force of a surprise upon the Queen's Majestie, and perhaps shook her certainty of the sway over her nobility, which she had been gradually acquiring, which was sufficient to make them defend her personal freedom and tolerate her faith, but not to pronounce a sentence which they felt to be unjust.

"John Knox being departed, the Table of the Lords, and others that were present were demanded every man by his vote, if John Knox had not offended the Queen's Majestie. The lords voted uniformly they could find no offence. The Queen had past to her cabinet, the flatterers of the Court, and Lethington principally, raged. The Queen was brought again and placed in her chair, and they commanded to vote over again, which thing highly offended the haill nobilitie so that they began to speak in open audience—'What! shall the Laird of Lethington have power to control us? or shall the presence of ane woman cause us to offend God and to dampen ane innocent, against our conscience for pleasure of any creature?' And so the haill nobilitie absolved John Knox again."

The Queen was naturally enraged at this decision, and taunted bitterly the Bishop of Ross, who joined in the acquittal, with following the multitude, to which he answered with much dignity, "Your Grace may consider that it is neither affection to the man nor yet love to his profession that moved me to absolve him, but the simple truth"—a noble answer, which shows that the entire body of prelates in Scotland were not deserving of the abuse which Knox everywhere and on all occasions pours upon them.

This was his last meeting with Mary. The part he played in public affairs was as great, and the standing quarrel with the Court, and all those who favoured it, more acrimonious than ever, every slanderous tale that came on the idle winds of gossip being taken for granted, and the most hideous accusations made in the pulpit as well as in private places against the Queen and her lighthearted company. The principles, of such profound importance to the nation, which were undoubtedly involved, are discredited by the fierce denunciations and miserable personal gossip with which they were mingled. That judgment should follow the exhibition of "tarjetted tails," i.e. embroidered or highly decorated trains, and loom black over a Court ball; and that Scotland should be punished because the Queen and her Maries loved dancing, were threats in no way inconsistent with the temper of the time; but they must have filled the minds of reasonable men with many revoltings of impatience and disgust. It says much for the real soundness of purpose and truth of intention among the exclusive Church party that they did not permanently injure the great cause which they had at bottom honestly at heart.

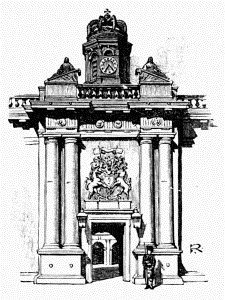

DOORWAY, HOLYROOD PALACE

CHAPTER III

THE TRIUMPH AND END

When the Assembly of the Church met in December shortly after these stirring incidents it was remarked that Knox took no part at first in the deliberations, an unexampled event. After the first burst of discussion, however, on the subject of the provision for the Church, he disclosed the reason of his unusual silence, which was that he had of late been accused of being a seditious man, and usurping power to himself—and that some had said of him, "What can the Pope do more than send forth his letters, and require them to be obeyed?" When one of the great officials present, no less a person than the Lord Justice-Clerk, took upon him to reply, Knox silenced him with a few emphatic words—"Of you I ask nothing," he said, "but if the Kirk that is here present do not either absolve me or else condemn me, never shall I, in public or in private, as ane public minister, open my mouth in doctrine or in reasoning." It is needless to say that the Kirk decided that it was his duty to advertise the brethren of danger whenever it might appear—but not without "long contention," probably moved by the party of the Court. At this period all the members of the nobility had been so universally acknowledged as having a right to be present at the Assembly sittings, that messengers were sent to advertise them of their guilt in absenting themselves when in the extremely strained character of the relations between Church and State they stayed away. There ensued, some time after, a singular conference between the leading ministers and the lords upon various matters, chiefly touching the conduct of John Knox, whose constant attacks upon the mass, his manner of praying for the Queen, and the views he had advanced upon obedience to princes, had given great offence not only at Court but among the moderate men who found Mary's sway, so far, a gentle and just one. This conference took the form of a sort of duel between Knox and Lethington, the only antagonist who was at all qualified to confront the Reformer. The comparison we have already employed returns involuntarily to our lips; the assault of Lethington is like that of a brilliant and chivalrous knight against some immovable tower, from the strong walls of which he is perpetually thrown back, while they stand invulnerable, untouched by the flashing sword which only turns and loses its edge against those stones. His satire, his wit, his keen perception of a weak point, are all lost upon the immovable preacher, whose determined conviction that he himself is right in every act and word is as a triple defence around him. This conviction keeps Knox from perceiving what he is by no means incapable by nature of seeing, the grotesque conceit, for instance, which is in his prayer for the Queen. During the course of the controversy he repeats the form of prayer which he is in the habit of using—being far too courageous a soul to veil any supposed fault. And this is the salvam fac employed by Knox:—

"Oh Lord! if Thy pleasure be, purge the heart of the Queen's Majesty from the venom of idolatry, and deliver her from the bondage and thraldom of Satan in the which she has been brought up and yet remains, for the lack of true doctrine; that she may avoid that eternal damnation which abides all obstinate and impenitent unto the end, and that this poor realm may also escape that plague and vengeance which inevitably follow idolatrie maintained against Thy manifest Word and the open light thereof." "This," Knox adds, "is the form of my common prayer as yourselves were witness. Now what is worthy of reprehension in it I would hear?"