Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Royal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

This manner of approaching a powerful statesman whose good offices might be of the uttermost consequence both to the writer and his party, is highly characteristic. There is something almost comic, if we dared to interpose such a view between two such personages, in the warning against "carnal wisdom and worldly policy to the which both ye are bruited too much inclined," addressed to the great Burleigh. It is difficult to imagine the outburst of a laugh between such a pair, yet grave Cecil surely must have smiled.

The man who wrote this epistle and many another, leagues of letters in no one of which does he ever mince matters, or refrain to deliver his conscience before conveying the message of State with which he is charged—is often wordy, sometimes tedious, now and then narrow as a village gossip, always supremely and absolutely dogmatic, seeing no way but his own and acknowledging no possibility of error; and the extreme and perpetual movement of his ever-active mind, his high-blooded intolerance, the restless force about him which never pauses to take breath, is the chief impression produced upon the reader by his own unfolding of himself in his wonderful history. Though he is too great and important to be called a busybody, we still feel sympathetically something of the suppressed irritation and sense of hindrance and interruption with which the lords must have regarded this companion with his "devout imaginations," whom they dared not neglect, and who was sure to get the better in every argument, generally by reason, but at all events by the innate force of his persistence and daring. But when they came to Stirling, after "that dusk and dolorous night wherein all ye my lords with shame and fear left the town", the eager nervous form, the dark keen face of the preacher, rose before the melancholy bands like those of the hero-leader, the standard-bearer of God. It was Wednesday the 7th of November 1559 when the dispirited Congregation met for the preaching and to consider afterwards "what was the next remedy in so desperate a case." Knox took for his text certain verses of the eightieth Psalm. "How long wilt thou be angry against the prayers of thy people? Thou hast fed us with the bread of tears; and hast given us tears to drink in great measure. O God of hosts, turn us again, make thy face to shine; and we shall be saved." He began by asking, Why were the people of God thus oppressed?

"Our faces are this day confounded, our enemies triumph, our hearts have quaked for fear, and yet they remain oppressed with sorrow and shame. But what shall we think to be the very cause that God hath thus dejected us? If I shall say our sins and former unthankfulness to God, I speak the truth. But yet I spake more generallie than necessity required: for when the sins of men are rebuked in general, seldom it is that man descendeth within himself, accusing and damning in himself that which most displeaseth God."

To this particular self-examination he then leads his hearers in order that they may not take refuge in generalities, but that each man may examine himself. "I will divide our whole company," he says, "into two sorts of men. The one, those who have been attached to the cause from the beginning; the other, recent converts."

"Let us begin at ourselves who longest has continued in this battle. When we were a few in number, in comparison with our enemies, when we had neither Erle nor Lord (a few excepted) to comfort us, we called upon God, we took Him for our protector, defence, and onlie refuge. Among us was heard no bragging of multitude or of our strength or policy, we did only sob to God, to have respect to the equity of our cause and to the cruel pursuit of the tyraneful enemy. But since that our number has been multiplied, and chiefly since my Lord Duke his Grace with his friends have been joined with us, there was nothing heard but 'This Lord will bring these many hundred spears: if this Earl be ours no man in such and such a bounds will trouble us.' And thus the best of us all, that before felt God's potent hand to be our defence, hath of late days put flesh to be our arm."

This proved, which was an evil he had struggled against with might and main, forbidding all compromises, all concessions that might have served to attract the help of the powerful, and conciliate lukewarm supporters, he turns to the other side.

"But wherein hath my Lord Duik his Grace and his friends offended? It may be that as we have trusted in them so have they put too much confidence in their own strength. But granting so be or not, I see a cause most just why the duke and his friends should thus be confounded among the rest of their brethren. I have not yet forgotten what was the dolour and anguish of my own heart when at St. Johnstone, Cupar Muir, and Edinburgh Crags, those cruel murderers, that now hath put us to this dishonour, threatened our present destruction. My Lord Duke his Grace, and his friends at all the three jornayes, was to them a great comfort and unto us a great discourage; for his name and authority did more affray and astonish us, than did the force of the other: yea, without his assistance they would not have compelled us to appoint with the Queen upon unequal conditions. I am uncertain if my Lord's Grace hath unfeignedly repented of his assistance to those murderers unjustly pursuing us. Yea, I am uncertain if he hath repented of that innocent blood of Christ's blessed martyrs which was shed in his default. But let it be that so he hath done, as I hear that he hath confessed his offence before the Lords and brethren of the Congregation, yet I am assured that neither he, nor yet his friends, did feel before this time the anguish and grieving of heart which we felt when they in their blind fury pursued us. And therefore hath God justly permitted both them and us to fall in this confusion at once; us for that we put our trust and confidence in man, and them because that they should feel in their own hearts how bitter was the cup which they had made others to drink before them. Rests that both they and we turn to the Eternal, our God (who beats down to death to the intent that He may raise up again, to leave the remembrance of His wondrous deliverance to the praise of His own name), which if we do unfeignedly, I no more doubt that this our dolour, confusion, and fear, shall be turned into joy, honour, and boldness, than that I doubt that God gave the victory to the Israelites over the Benjaminites after that twice with ignominy they were repulsed and dang back. Yea, whatsoever shall come of us and our mortal carcasses, I doubt not but this cause in despite of Satan shall prevail in the realm of Scotland. For as it is the eternal truth of the eternal God, so shall it once prevail, however for a time it may be hindered. It may be that God shall plague some, for that they delight not in the truth, albeit for worldly respects they seem to favour it. Yea, God may take some of His devout children away before their eyes see greater troubles. But neither shall the one or the other so hinder this action but in the end it shall triumph."

When the sermon was ended, Knox adds, "The minds of men began wonderfully to be erected." "The voice of one man," as Randolph afterwards said, was "able in an hour to put more life in us than six hundred trumpets continually blustering in our ears." The boldness with which Knox thus exposed that elation in their own temporary success, and in the adhesion of the Duke of Hamilton, which had led the leaders of the Congregation into self-confidence and slackened their watchfulness, was made solemn and authoritative by the force with which he pressed his personal responsibility into every man's bosom. No turn of fortune, no evil fate, but God's check upon an army enlisted in His name yet not serving Him with a true heart, was this momentary downfall; the cause of which was one that every man could remove in his degree; not inherent weakness or hopeless fate, but a matter remediable, nay, which must be remedied and cast from among them—a matter which might quench their personal hopes and destroy them, but could not affect the divine cause, which should surely, triumph whatever man or Satan might do. More than six hundred trumpets, more than the tramp of a succouring army, it rang into the men's hearts. Their spirit and their courage rose; the dolorous night, the fear and shame, dissolved and disappeared; and the question what to do was met not with dejection and despair but with a rising of new hope.

The decision of the Congregation in the Senate which was held after this stirring address was, in the first place, to address an appeal for help to England, the sister-nation which had already made reformation, though not in their way, and to fight the matter out with full confidence in a happy issue. About this appeal to England, however, there were difficulties; for Knox who suggested it, and whose name could not but appear in the matter, had given forth, as all the world and especially the persons chiefly attacked were aware, a tremendous "blast" against the right of women to reign, particularly well or ill timed in a generation subject to so many queens; and it was necessary for him to excuse or defend himself to the greatest of the female sovereigns whom he had attacked. Of course it was easy for him to say that he had no great Protestant Elizabeth in his eye when he wrote, but only a bigoted and sanguinary Mary, of whom no one knew at the time that her reign was to be short, and her power of doing evil so small. It is almost impossible to discuss gravely nowadays a treatise which, even in its name (which is all that most people know of it), has the air of a whimsical ebullition of passion, leaning towards the ridiculous, rather than a serious protest calculated to move the minds of men. But this was not the aspect under which it appeared to the Queens who were assailed, not as individuals, but as a class intolerable and not to be suffered; and it was considered necessary that Knox should write to excuse himself, and apologise as much as was in him to the Queen, who was now the only person on earth to whom the Congregation could look for help. Knox's letter to Queen Elizabeth, whom he addressed indeed more as a lesser prince, respectful but more or less equal, might do, than as a private individual, is very characteristic. He has to apologise, but he will not withdraw from the position he had taken. "I cannot deny the writing," he says, "neither yet am I minded to retreat or call back any principal point or proposition of the same." But he is surprised that subject of offence should be found in it by her for whose accession he renders thanks to God, declaring himself willing to be judged by moderate and indifferent men which of the parties do most harm to the liberty of England, he who affirms that no woman may be exalted above any realm to make the liberty of the same thrall to any stranger nation, "or they that approve whatsoever pleaseth Princes for the time." Leaving thus the ticklish argument which he cannot withdraw, but finds it impolitic to bring forward, he turns to the Queen's individual behaviour in her position as being the thing most important at the present moment, now that she has effectively attained her unlawful elevation.

"Therefore, Madam, the only way to retain and keep those benefits of God abundantly poured now of late days upon you and upon your realm, is unfeignedly to render unto God, to His mercy and undeserved grace, the glory of your exaltation. Forget your birth, and all title which thereupon doth hing: and consider deeply how for fear of your life ye did decline from God and bow till idolatrie. Let it not appear ane small offence in your eyes that ye have declined from Christ in the day of His battle. Neither would I that you should esteem that mercy to be vulgar and common which ye have received: to wit that God hath covered your former offence, hath preserved you when you were most unthankful, and in the end hath exalted and raised you up, not only from the dust, but also from the ports of death, to rule above His people for the comfort of His kirk. It appertaineth to you, therefore, to ground the justice of your authority, not upon that law which from year to year doth change, but upon the eternal providence of Him who contraire to nature and without your deserving hath thus exalted your head. If then, in God's presence ye humble yourself, as in my heart I glorify God for that rest granted to His afflicted flock within England under you a weik instrument: so will I with tongue and pen justify your authority and regiment as the Holy Ghost hath justified the same in Debora that blessed mother in Israel. But if the premisses (as God forbid) neglected, ye shall begin to brag of your birth and to build your authority and regiment upon your own law, flatter you who so list your felicity shall be short. Interpret my rude words in the best part as written by him who is no enemy to your Grace."

It must have been new to Queen Elizabeth to hear herself called "a weik instrument," and it is doubtful whether the first offence would be much softened by such an address. Neither was Elizabeth a person to be amused by the incongruity or impressed by the uncompromising boldness of the Reformer to whom the language of apology was so hard. Policy, however, has little to do with personal offences, although to some readers, as we confess to ourselves, it may be more interesting to see the prophet thus arrested, hampered by his own trumpet-blast, and making amends as much as he can permit himself to make, though so awkwardly and with so bold a return upon the original offence, to the offended Queen. It was far more easy for him to warn her of what would happen did she fail in her duty than to soothe the affront with gentle words; and his attempt at the latter is but halting and feeble. But when he promises with tongue and pen to justify her if she does well, Knox is once more on his own ground—that of a man whose office is superior to all the paltry distinctions of kingship or lordship, a servant of God commissioned to declare His divine will, endowed with an insight beyond that of ordinary men, and declaring with boundless certainty and confidence the things which are to be.

We may, however, pass very shortly over the coming struggle. The English army marched into Scotland in April 1560, and addressed itself at once to the siege of Leith, the headquarters of the French whom the Queen Regent had brought into Scotland, and whom it was the chief aim of the Congregation and of their allies to drive out of the country. The siege went on for about six weeks, during which little effect seems to have been made, though Knox bears testimony that "the patience and stout courage of the Englishmen, but principally of the horsemen, was worthy of all praise." These proceedings, however, were brought to a pause by an event which changed the position of affairs. The Queen Regent, who, for some time, had been in declining health, harassed and beaten down by many cares, had left Leith and taken up her abode in Edinburgh Castle while the Reformers were absent from the capital. In that fortress, held neutral by its captain, in the small rooms where, some seven years after, her daughter's child was to be born, Mary lingered out the early days of summer: and in June, while still the English guns were thundering against Leith, her new fortifications resisting with diminished strength, and her garrison in danger—died, escaping from her uneasy burden of royalty when everything looked dark for her policy and cause. Many anecdotes of her sayings and doings were current during her lingering illness, such as might easily be reported between the two camps with more or less truth. When she heard of the "Band" made by the leaders of the army before Leith for the expulsion of the strangers she is said to have called the maledictions of God upon them who counselled her to persecute the preachers and to refuse the petitions of the best part of the subjects of the realm. Shut out from the countrymen and advisers in whom she had trusted, with the hitherto impartial Lord Erskine alone at her ear, adding his word concerning the "unjust possessors" who were to be driven "forth of this land," and overcome by sickness, sadness, and loneliness, this lady, who had done her best to hold the balance even and to refrain from bloodshed, though she had little credit for it, seems to have lost courage. She saw from her altitude on the castle rock the great fire in Leith, which probably looked at first like the beginning of its destruction, and all the martial bands of England, and the Scots lords and their followers, lying between her and her friends. After some ineffectual efforts to communicate with them otherwise, she sent for the Lords Argyle, Glencairn, and the Earl Marischal, with the Lord James, who visited her separately, "not all together, lest that some part of the Guysian practice had lurked under the colour of friendship." Knox's heart was not softened by the illness and isolation, nor even by the regrets and repentance, of the dying Queen. She consented to see John Willock, his colleague, and after hearing him "openly confessed that there was no salvation but in and by the death of Jesus Christ." "But of the Mass we had not her confession," says the implacable preacher. She died on the 9th of June, worsted, overthrown, all that she had aimed at ending in failure, all her efforts foiled, leaving those who had been her enemies triumphant, and the future fate of her daughter's kingdom in the hands of "the auld enemy," the ever-dangerous neighbour of Scotland. "God, for His good mercy's sake, rid us from the rest of the Guysian blood," was the prayer Knox made over her grave.

And yet, so far as can be judged, Mary of Guise was no persecutor and no tyrant. To all appearance she had honestly intended to keep peace in the kingdom, to permit as much as she could without committing herself to views which she did not share. And nothing could be more touching than such an end to a life never too brilliant or happy. She had gone through many alternations of gladness and of despair, had stood bravely by her sensitive husband when the infant sons who were his hope had been taken one after another, had discharged, as faithfully as circumstances and the accidents of a tremendous crisis would let her, her duties as Regent. Her death, lonely, desolate, and defeated, with no one near whom she loved, to smooth her passage to the grave, might have gained her a more gentle word of dismissal.

Within little more than a month after her death peace was signed; the French forces departed, and the English army, not much more loved in its help than the others in their hostility, was escorted back to the Border and safely got rid of. On the 19th of July, all being thus happily settled, St. Giles's was once more filled with a crowd of eager worshippers, "the haill nobilitie and the greatest part of the Congregation,"—a number which must have tried the capacity of the great church, large as it is. Knox does not give his sermon on the occasion, but we have a very noble and devout prayer, or rather thanksgiving, which was used at this service, and in which, though there is one reference to "proud tyrants overthrown," the spirit of devout thankfulness is predominant. He tells us, however, that the subject of his discourses, delivered daily, were the prophecies of Haggai, which he found to be "proper for the time." Some of his hearers, he informs us, spoke jestingly of having now to "bear the barrow to build the house of God." "God be merciful to the speaker," cries the stern prophet, "for we fear he shall have experience that the building of his ain house, the house of God being despised, shall not be so prosperous or of such firmity as we desire it were"—so dangerous was it to jest in the presence of one so tremendously in earnest. The speaker referred to, of this, as of most of the other caustic sayings of the time, is said to have been Lethington.

The first thing done by the Parliament was the distribution of the handful of ministers then existing among the districts which most needed them; the second, the verification and establishment of the Confession of Faith. No more curious scene could have been than this momentous ceremony. The Parliament consisted of all the nobility of Scotland, including among them the bishops and peers of the Church, and the delegates from the boroughs. The Confession was read article by article, and a vote taken upon each. Three only of the lords voted against it. The bishops said nothing. What their feelings must have been, as they sat in their places looking on, while the long array of the Congregation voted, it is vain to attempt to imagine. There was nothing the Reformers would have liked better than that discussion to which Knox had vainly bidden his opponents, throwing down his glove as to mortal combat. "Some of our ministers were present," he says, "standing upon their feet ready to have answered in case any would have defended the Papistrie and impugned our affirmations." But no one of all the ecclesiastics present said a word. The Earl Marischal, when he rose in his turn to vote, commented upon this remarkable abstinence with the straightforwardness of a practical man. "It is long since I have had some favour to the truth," he said, "and since I have had a suspicion of the Papistical religion; but I praise my God this day has fully resolved me in the one and the other. For, seeing that my Lord Bishops here present, who for their learning can, and for the zeal they should bear to the veritie would, I suppose, gainsay anything that directly repugns to the veritie of God, speaks nothing in the contraire of the doctrine proposed, I cannot but hold it to be the very truth of God." Even this speech moved the bishops to no reply. They sat silent, perhaps too much astonished at such an extraordinary revolution to say anything; perhaps alarmed at the strength of the party against them. It might be that there was little learning among them, though they had the credit of it; certainly the arguments which Knox reports on several occasions are inconceivably feeble on the side of the old faith. But whatever was the meaning there they sat dumb, and looked on bewildered, confounded, while the new Confession was voted paragraph by paragraph, and the whole scope of the Scottish constitution changed.

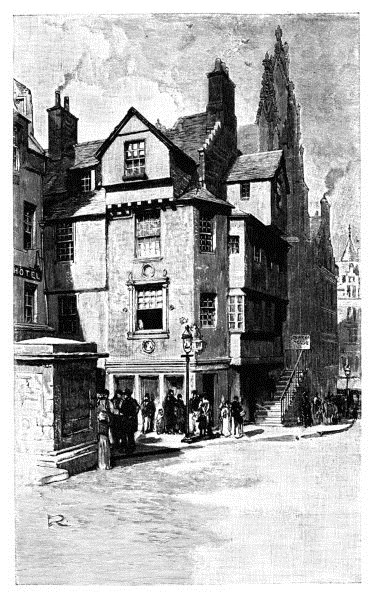

KNOX'S HOUSE, HIGH STREET

The next step was the abolition of the mass, an act by which it was forbidden that any should either hear or say that office "or be present thereat, under the pain of confiscation of all their goods movable and immovable, and punishing of their bodies at the discretion of the Magistrates." Another edict followed abolishing the jurisdiction of the Pope under pain of "proscription, banishment, and never to brook honour, office, or dignity within this realm." "These and other things," says the Reformer, "were orderly done in lawful and free Parliament," with the bishops and all spiritual lords in their places sitting dumb and making no sign. The Queen was at liberty to say afterwards, as was done, that a Parliament where she was not represented in any way, either by viceroy or regent, where there was no exhibition of sceptre, sword, or crown, and in short where the monarch was left out altogether, was not a lawful Parliament. But the most remarkable feature of this strange assembly amid all the voting and "bruit" is the dramatic silence of the State ecclesiastical. It is curious that no fervent brother should have been found to maintain the cause of his faith. But probably it was better policy to refrain. The extraordinary absence of logic as well as toleration which made the Reformers unable to see what a lame conclusion this was after their own struggle for freedom, and that they were exactly following the example of their adversaries, need not be remarked. John Knox thought it a quite sufficient answer to say that the mass was idolatry and his own ways of thinking absolutely and certainly true; but so of course has the Roman Catholic Church done when the impulse of persecution was strongest in her. There is one only thing to be said in favour of the Reformers, and that is, that while a number of good men had been sacrificed at the stake for the Reformed doctrines, no one was burned for saying mass; the worst that happened, notwithstanding their fierce enactments, being the exposure in the pillory of a priest. Rotten eggs and stones are bad arguments either in religion or metaphysics, but not so violently bad as fire and flame.