Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Royal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

"To stay them was first sent the Provost of Dundee and his brother Alexander Halliburton Capitain, who little prevailing was sent unto them John Knox; but before his coming they were entered to the pulling down of the idols and dortour (dormitory). And albeit the said Maister James Halliburton, Alexander his brother, and the said John, did what in them lay to have stayed the fury of the multitude, yet were they not able to put order universalie; and therefore they sent for the lords, Earl of Argyle and Lord James, who coming with all diligence laboured to have saved the palace and the kirk. But because the multitude had found buried in the kirk a great number of idols, hid of purpose to have reserved them for a better day (as the Papists speak) the towns of Dundee and St. Johnstone could not be satisfied till that the whole reparation and ornaments of the church (as they term it) were destroyed. And yet did the lords so travel that they saved the Bishop's palace with the church and place for that night; for the two lords did not depart till they brought with them the whole number of those who most sought the Bishop's displeasure. The Bishop, greatly offended that anything should have been enterprised in reformation of his place, asked of the lords his bond and handwriting, which not two hours before he had sent to them (this was a promise to come immediately to arrange for the safety of his see, and also to support them in Parliament in gratitude for the warning they had given him); Which delivered to his messenger, Sir Adam Brown, advertisement was given that if any further displeasure chanced unto him that he should not blame them. The Bishop's servants that same night began to fortify the place again, and began to do violence to some that were carrying away such baggage as they could come by. The Bishop's girnel was kept the first night by the labours of John Knox, who by exhortation removed such as would violentlie have made irruption. The morrow following, some of the poor in hope of spoil, and some of Dundee to consider what was done, passed up to the said Abbey of Scone; whereat the Bishop's servants offended began to threaten and speak proudly, and as it was constantly affirmed one of the Bishop's sons stogged through with a rapier one of Dundee because he was looking in at the girnel door. This bruit noised abroad, the town of Dundee was more enraged than before, who putting themselves in armour sent word to the inhabitants of St. Johnstone, 'That unless they should support them to avenge that injury, that they should never from that day concur with them in any action.' They, easilie inflambed, gave the alarm, and so was that abbey and palace appointed to the saccage; in doing whereof they took no long deliberation, but committed the whole to the merriment of fire; whereat no small number of us was so offended, that patientlie we could not speak to any that were of Dundee or Saint Johnstone."

The reader will see in this frank narrative how many elements were conjoined to bring about the outrage. Local jealousy and despite, the rage against the Bishop and his priests, the eagerness of the needy in hope of spoil, the excitement of a fray in which the first blow had been struck by the adversary with just the crown of a supposed religious motive to give the courage of a great cause to the rioters: while on the other hand the Bishop's rashness in taking the defence upon himself and slighting the assistance offered him is equally apparent. It is evident enough, however, that the lords themselves had no urgent interest in the preservation of the ancient buildings, and that Knox cared little for any of these things. The watch of the preacher at the door of the Bishop's girnel or storehouse, keeping back the rioters by his exhortations, is a curious illustration of this point. He would not have the people soil their souls with thieving, with the Bishop's meal and malt; as for the historical walls, the altar where the old kings had been anointed or the sanctuary where their ashes lay, what were they? Knox was too much intent on setting Scotland loose from all previous traditions—from the past which was idolatrous and corrupt, and in which till it reached to the age of the Apostles he recognised no good thing—to be concerned about the temples of Baal. What he wanted was to cut all these dark ages away, and affiliate himself and his country direct to Judæa and Jerusalem, to the Jewish church, not the Gothic or the papal, or any perverted image of what he believed primitive Christianity to have been. He served himself heir to Peter and Paul, to Elijah and Ezekiel, and perhaps in the strong prepossession of his soul against contemporary monks and ecclesiastics did not even know that the Church which was so corrupt, and the religious orders which had fallen so low, had ever brought or preserved light and blessing to the world. Scottish history, Scottish art, were corrupted too, and woven about with associations of these hated priests and their system which was not true religion, but "devised by the brain of man"; and though he was himself the most complete incarnation of Scotch vehemence, dogmatism, national pride, and fiery feeling, he was indifferent to their national records. His pride was involved in making his country stand, alone if need was, or if not alone, then first, in passionate perfection in the new order of things in the kingdom of Christ: not to keep her a place in the unity of nations by preserving the traces of an old civilisation and institutions as venerable and noteworthy as any in Christendom, but to make of her a chosen nation like that people, long ago dispersed by a sufficiently miserable catastrophe, to whom was given of old the mission of showing forth the will of God before the world. Whether what he gained for his country was not much more important than what he thus deliberately sacrificed is a question that will never be answered with any unanimity. He gained for his race a great freedom, which cannot be justly called religious freedom, because it was, in his intention at least, freedom to follow their own way, with none at all for those who differed from them. He set up a high standard of piety and probity, and for once made the business of the soul, the worship of God and study of His laws, the most absorbing of public interests. He thrilled the whole country through and through with the inspiration of a fervent spirit, uncompromising in its devotion to the truth, asking no indulgence if also, perhaps, giving none, serving God in his own way with a fidelity above every bribe, scornful of every compromise. But he cut Scotland adrift so far as in him lay from the brotherhood of habit and tradition, from the communion, if not of saints, yet of many saintly uses, and much that is beautiful in Christian life. He made his country eminent, and secured for her one great chapter in the history of the world; but he imprinted upon her a certain narrowness uncongenial to her character and to her past, which has undervalued her to many superficial observers, and done perhaps a little, but a permanent, harm to her national ideal ever since. A small evil for so much good, but yet not to be left unacknowledged.

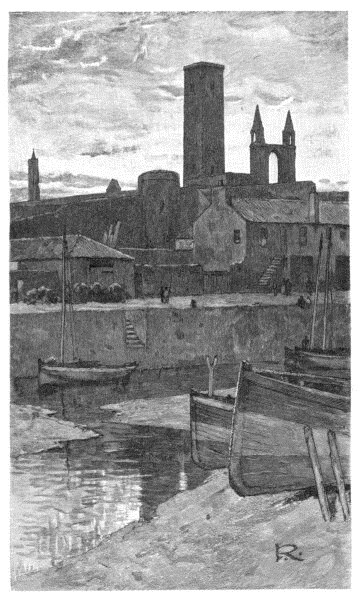

More interesting in its human aspect is Knox's appearance in St. Andrews, whither the Congregation now crowded to "make reformation," though doubtful if even the populace were on their side. The Bishop "hearing of reformation to be made in his cathedral church, thought time to stir, or else never"—which was very natural. He was accompanied by a hundred spears, which must have meant a company at least of four or five hundred armed men, while the Lords of the Congregation had "their quiet households," no doubt a very adequate escort. The Bishop threatened that if John Knox showed his face in the cathedral he should be saluted with a dozen of culverins, and the gentlemen with him hesitated much to expose him to such a risk: but their doubts were not shared by the preacher. He had himself given forth, when in the galley labouring at the oar in sight of the beloved town and sanctuary, a prophecy that he should yet preach there, unlikely as it looked; and to recoil from any danger, when such an opportunity arose, was not in him. "To delay to preach the morrow (unless the bodie be violentlie witholden) I cannot," he said. He preached upon the casting out of the money-changers from the Temple—a very dangerous subject for such an occasion, and "applied the corruption that was there to the corruption that is in the Papestrie" so well that the magistrates of the town, and also the commonalty "for the most part, did agree to remove all monuments of idolatrie, which also they did with expedition." But it was not on that day that the great church shining from afar on its rocky headland, a splendid landmark over the dangerous bay, was reduced to the condition in which it now remains, with a few forlorn but graceful pinnacles rising against the misty blue of sea and sky. No harm would seem to have been done except to the altars and the decorations; and according to all evidence it is more to the careless brutality of the eighteenth century, which found an excellent storehouse of materials for building in the abandoned shrine, than to any absolute outrage that its present state of utter ruin is due.

ST. ANDREWS

The Congregation set forth on its march to Stirling, and thence to Edinburgh in June, and so great was the commotion which had been raised by the rumour of the "reformation" wrought in the north in Scone and St. Johnstone that the mere news of their approach roused "the rasckall multitude" to the mood of destruction. They had cleared out and destroyed the convents in Stirling, and those of the Black and Grey Friars in Edinburgh, before the Reformers came—a result which Knox at least in no way pauses to deplore: they had left nothing, he says, "but bare walls, yea, not so much as door or windok: wherthrou we were the less troubled in putting order in such places." Thus the flood of Revolution, of Reformation, of fundamental, universal change flowed on. The victory was not assured, however, as perhaps they had hoped when they entered Edinburgh, for though for a time everything went well, and the preaching seems to have been followed by the greater part of the city, the Queen, ever active, though never striking any decisive blow, had received reinforcements from France, and to the great alarm of the Congregation had begun to fortify Leith, forming a strong garrison there of French soldiers, and making a new stronghold near enough to be a perpetual menace to Edinburgh almost at her door. The position of affairs at this moment was curious in the extreme. The Queen in Leith, surrounded by the newly arrived forces of France, with Frenchmen placed in all the great offices, fulminated forth decrees, commands, explanations, orders, from within the walls that were being quickly raised to make the fort a strong place, and from amidst the garrison of her own countrymen, in whose fidelity she could fully trust. In Edinburgh the Congregation were virtually supreme, but very uneasy; their substantial adversaries quieted, but ever on the watch; the populace ready to pull down and destroy at their indication, but not to change their life or character—an unstable support should trouble come; while in the castle Lord Erskine sat impartial, a sort of silent umpire, taking neither side, though ready to intervene with a great gun on either as occasion moved him. The fire of words which was kept up between the two parties is one of the most amazing features of the conflict. For every page the Queen's secretaries wrote, John Knox was ready with ten to demonstrate her errors, her falsehood, the impossibility that any good could come from an idolater such as she. Other persons take part in the great wrangle, but he is clearly the scribe and moving spirit. He writes to her in his own person, in that of the Lord James, in that of the Congregation. She accuses them of rebellion and treasonable intentions against herself—and they her of her Frenchmen and her fortifications. She summons them to leave Edinburgh on peril of all the penalties that attend high treason; they demand from her that the Frenchmen should be sent away and the proceedings stopped. She accuses the Duke Chatelherault—the head of the Hamiltons, the next heir to the throne—of treasonable proceedings, and he vindicates himself by sound of trumpet at the Cross of Edinburgh. The correspondence grows to such a pitch that when she loses patience and bids them be gone before a certain day, they meet in solemn conclave, to which the preachers are called to give their advice, to discuss whether it is lawful to depose her from her regency: and all consent with one voice to her deprivation. The excitement of this continual exchange of correspondence, the messages coming and going, from the Queen's side the Lyon King himself, all glorious among his pursuivants, advancing from Leith with his brief letter and his "credit" as spokesman, the others replying and re-replying, scarcely ever without a response or a denunciation to read over and talk over, must have kept the nerves and intelligence of all at a perpetual strain. At St. Giles's and the Tolbooth close by, which were the double centre of life in the city, there was a perpetual alternation of preachings, to which Lords and Commons would crowd together to listen to Knox's trumpet peals of fiery eloquence, always upon some appropriate text, always instinct with the most vehement energy, and consultations upon public affairs and how to promote the triumph of religion; the lords pondering and sometimes doubtful, the preacher ever uncompromising and absolute. A question of public honesty had arisen in the midst of the struggle for the faith, and the Reformers had seized the Mint to prevent the coining of base money, which the Regent was carrying on for her necessities, and which the Congregation, no doubt justly, considered ruinous to the trade of the country; and the determined struggle with the Queen in respect to her scheme for fortifying Leith and establishing a French garrison there,—a continual check upon and menace to the freedom of the capital,—was at least as much a question of politics as religion.

The Congregation, however, was not yet strong enough to be able to meet the French forces, and when they attempted to besiege Leith and put a forcible stop to the building they were defeated with shame and loss. A curious sign of the inevitable "rift within the lute," which up to this time had been avoided by the concentration of all men's thoughts upon the first necessity of securing the freedom of the preachings, becomes visible before this futile attempt at a siege. When the leaders of the Congregation, among whom on this occasion the contingent from the towns, and especially from Dundee, seems foremost, began to prepare for their expedition, they chose St. Giles's Church as the most convenient for the preparation of the scaling ladders, a practical evidence that sacredness had departed from the church as a building, not at all to the mind of the preachers, who probably saw no logical succession between the hammers of the destroyers pulling down the "glorious tabernacles" and those of the craftsmen occupied with secular work. They did not, indeed, put their objections on this ground, but on that of the neglect of the "preaching," a name now characteristically applied to the public worship of God. "The Preachers spared not openly to say that they feared the success of that enterpryse should not be prosperous because the beginning appeyred to bring with it some contempt of God and of His word. Other places, said they, had been more apt for such preparations than where the people convened to common prayer and unto preaching, and they did not hesitate to affirm that God would not suffer such contempt of His word." Whether these objections stole the heart out of the fighting men, who had hitherto felt themselves emphatically the soldiers of God, it is impossible to say. They had hitherto overawed the Queen's party by their numbers, and had never outwardly made proof of their powers or sustained the attack of regular soldiers. And the assault of Leith ended in a disastrous defeat. The expedition set out rashly without leaders, while the lords and gentlemen "were gone to the preaching," and had consequently no accompanying cavalry, and few, if any, experienced soldiers. They were driven back with loss, and pursued into the very Canongate, to the foot of Leith Wynd—that is, into the cross-roads and narrow wynds which were immediately outside the city walls. Argyle and the rest, as soon as they were aware of what had happened, got hastily to horse, and did all they could to stop the flight, but even this turned to harm, since the horsemen coming out to the aid of their friends proved an additional danger to the fugitives, and "over-rode their poor brethren at the entrance of the Nether Bow."

After this all was confusion and trouble in Edinburgh. The castle fired one solitary gun, which stopped with a note of sudden protest the French pursuit, coming with extraordinary dramatic effect into the always graphic and picturesque narrative, over the heads of the flying, discomfited crowd which was struggling among the horses' hoofs at the narrow gate, and the Frenchmen straggling behind, up all the narrow passages into the Canongate, snatching a piece of plunder where they could find it, "one a kietill, ane other ane pettycoat, the third a pote or a pan." "Je pense que vous l'avez acheté sans argent," the Queen is reported to have said with a laugh as the pursuers came back to Leith with their not very important booty. "This was the great and motherlie care she took for the truth of the poor subjects of this realm," says Knox bitterly; and yet it was very natural that she should have been overjoyed, after all these controversies, to feel herself the stronger, if not in argument at least in actual fight.

This defeat told greatly upon the spirits of the Congregation which had hitherto been kept together by success, and which was in fact a mere horde of men hastily collected, untrained in actual warfare, and in no position for taking the offensive though strong in defence of their rights. And money had failed. It was determined that each gentleman should give his plate to be made into coin to supply the needs of the Congregation, as they had the Mint in their hands: but the officials stole away with the "irons" and this was made impracticable. They then sent for a supply to the English envoys who were anxiously watching the progress of events at Berwick: but the sum sent to them in answer to their application was intercepted by the Earl of Bothwell—his first appearance in history, on which he was to leave thereafter such traces of disaster. And other encounters with the Frenchmen took the heart entirely out of the Congregation; the party began to dissolve, stealing away on every side. "Our soldiers" (mercenaries it is to be supposed in distinction from the retainers of the lords and gentlemen) "could skarslie be dang out of the town" to meet a sally from Leith. In Edinburgh itself the rasckall multitude, which had been so ready to destroy and ravage, began to throw stones at the Reformers and call them traitors and heretics. Finally with hearts penetrated by disappointment and the misery of defeat the Congregation abandoned Edinburgh altogether and marched to Stirling with drooping arms and hearts.

"The said day at nine in the night," says a contemporary authority, "the Congregation departed forth of Edinburgh to Linlithgow and left their artillerie void upon the causeway lying, and the town desolate." It was November, and the darkness of the night could not have been more dark than the prospects and thoughts of that dejected band, a little while before so triumphant. As the tramp of the half-seen procession went heavily down the tortuous streets at the back of the castle, probably by the West Bow and West Port, diving down into the darkness under that black shadow where the garrison sat grimly impartial taking no part, the populace, perhaps frightened by the too great success of their own fickle and cruel desertion of the cause, and hoping little from the return of the priests, would seem to have beheld with silent dismay the departure of the Congregation. The guns which had done them so little service which they left on the road, as the preachers would have had them leave all the devices and aid of men, were gathered in by the soldiers from the castle with little demonstration, and the town was left desolate. The anonymous writer of the Diurnal of Occurrents is curiously impartial and puts down his brief records without any expression of feeling: but a certain thrill is in these words as of something too impressive and significant to be passed by.

It is at this miserable moment that John Knox shows himself at his best. Hitherto his vehemence, his fierce oratory, his interminable letters and addresses, though instinct with all the reality of a most vigorous, even restless nature, represent to us rather a man who would if he could have done everything,—the fighting and the protocolling as well as the preaching, a man to whom repose was impossible, ever ready to draw forth his pen, to mount his pulpit, to add his eager word to every consultation, and enjoying nothing so much as to press the most unpleasant truths upon his correspondents and hearers,—than one of sustaining power and wisdom. The uncompromising fidelity with which he pointed out the shortcomings of those about him, and the terrible penalties laid up for them; and the stern denunciations in his letters, even those which he intended to be conciliatory, make his appearance in general more alarming than reassuring. An instance which almost tempts a smile, grave as are all the circumstances and surroundings, is his letter (written some time before the point at which we have now arrived) to Cecil whom he had known in England, and whose favour he desired to secure and indeed was confident of securing. For once he had something to ask for himself, permission to land in England on his way back to his native country; and greatly desired that a favourable representation of his case might be made to Queen Elizabeth, who was naturally prejudiced against him by his famous Blast against the Monstrous Regiment of Women. The following letter was written from Dieppe in April 1559 with the hope of procuring these favours from the great statesman.

"As I have no plaisure with long writing to trouble you, Rycht Honourable, whose mind I know to be occupied with most grave matters, so mind I not greatly to labour by long preface to conciliate your favour, which I suppose I have already (howsomever rumours bruit the contrarie) as it becometh one member of Christ's body to have of another. The contents, therefore, of these my presents shall be absolved in two points. In the former I purpose to discharge in brief words my conscience towards you, and in the other somewhat I must speik in my own defence and in defence of that poor flock of lait assembled in the most godly Reformed church and city of the world Geneva. To you Sir, I say, that as from God ye have received life, wisdom, honours and this present estate in which ye stand, so ought you wholly to employ the same to the advancement of His glory, who only is the Author of life, the fountain of wisdom, and who, most assuredly, doth and will honour those that with simple hearts do glorify Him; which, alas, in times past ye have not done; but being overcome with common iniquity ye have followed the world in the way of perdition. For to the suppressing of Christ's true Evangell, to the erecting of idolatrie, and to the shedding of the blood of God's dear children, have you by silence consented and subscribed. This, your most horrible defection from the truth known and once professed, hath God to this day mercifully spared; yea, to man's judgement He hath utterly forgotten and pardoned the same. He hath not entreated you as He hath done others (of like knowledge), whom in His anger (but yet most justly according to their deserts) He did shortly strike after their defection. But you, guilty in the same offences, He hath fostered and preserved as it were in His own bosom. As the benefit which ye have received is great, so must God's justice require of you a thankful heart; for seeing that His mercy hath spared you being traitor to His Majesty; seeing, further, that among your enemies He hath preserved you; and last, seeing that although worthy of Hell He hath promoted you to honour and dignity, of you must He require (because He is just) earnest repentance for your former defection, a heart mindful of His merciful providence, and a will so ready to advance His glory that evidently it may appear that in vain ye have not received these graces of God—to performance whereof of necessity it is that carnal wisdom and worldly policy (to the which both ye are bruited too much inclined) give place to God's simple and naked truth—very love compelleth me to say that except the Spirit of God purge your heart from that venom which your eyes have seen to be destruction to others, that ye shall not long escape the reward of dissemblers. Call to mind what you ever heard proclaimed in the chapel of Saint James, when this verse of the first Psalm was entreated, 'Not so, oh wicked, not so; but as the dust which the wind hath tossed, etc.' … And this is the conclusion of that which to yourself I say. Except that in the cause of Christ's Evangel ye be found simple, sincere, fervent and unfeigned, ye shall taste of the same cup which politic heads have drunken before you."