Полная версия:

Favourite Cat Stories: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, Kaspar and The Butterfly Lion

Michael Morpurgo

Favourite Cat Stories:

The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, Kasper and The Butterfly Lion

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips

Kasper

The Butterfly Lion

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Michael Morpurgo

Copyright

About the Publisher

For Ann and Jim Simpson, who brought us to Slapton, and for their family too, especially Atlanta, Harriet and Effie.

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

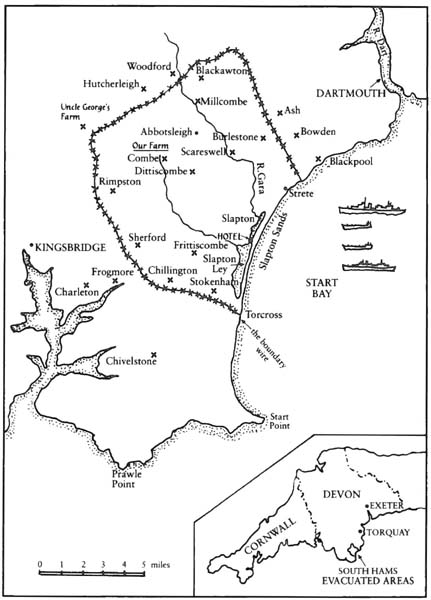

Map

Chapter 1

Friday, September 10th 1943

Sunday, September 12th 1943

Thursday, September 16th 1943

Friday, September 17th 1943

Monday, September 20th 1943

Tuesday, October 5th 1943

Monday, November 1st 1943

Monday, November 8th 1943

Saturday, November 13th 1943

Tuesday, November 16th 1943

Tuesday, November 30th 1943

Wednesday, December 1st 1943

Wednesday, December 15th 1943

Thursday, December 16th 1943

Saturday, December 18th 1943

Thursday, December 23rd 1943

Saturday, December 25th 1943

Sunday, December 26th 1943

Monday, December 27th 1943

Tuesday, December 28th 1943

Thursday, December 30th 1943

Friday, December 31st 1943

Wednesday, January 12th 1944

Wednesday, January 19th 1944

Monday, January 24th 1944

Thursday, February 10th 1944

Friday, February 11th 1944

Thursday, February 24th 1944

Friday, March 3rd 1944

Tuesday, March 7th 1944

Wednesday, March 8th 1944

Wednesday, March 15th 1944

Monday, March 20th 1944

Wednesday, March 29th 1944

Thursday, April 20th 1944

Friday, April 28th 1944

Monday, May 1st 1944

Wednesday, May 10th 1944

Saturday, May 20th 1944

Monday, May 22nd 1944

Friday, May 26th 1944

Tuesday, June 6th 1944

Thursday, October 5th 1944

Friday, October 6th 1944

Postscript

Acknowledgements

I first read Grandma’s letter over ten years ago, when I was twelve. It was the kind of letter you don’t forget. I remember I read it over and over again to be sure I’d understood it right. Soon everyone else at home had read it too.

“Well, I’m gobsmacked,” my father said.

“She’s unbelievable,” said my mother.

Grandma rang up later that evening. “Boowie? Is that you, dear? It’s Grandma here.”

It was Grandma who had first called me Boowie. Apparently Boowie was the first “word” she ever heard me speak. My real name is Michael, but she’s never called me that.

“You’ve read it then?” she went on.

“Yes, Grandma. Is it true – all of it?”

“Of course it is,” she said, with a distant echoing chuckle. “Blame it on the cat if you like, Boowie. But remember one thing, dear: only dead fish swim with the flow, and I’m not a dead fish yet, not by a long chalk.”

So it was true, all of it. She’d really gone and done it. I felt like whooping and cheering, like jumping up and down for joy. But everyone else still looked as if they were in a state of shock. All day, aunties and uncles and cousins had been turning up and there’d been lots of tutting and shaking of heads and mutterings.

“What does she think she’s doing?”

“And at her age!”

“Grandpa’s only been dead a few months.”

“Barely cold in his grave.”

And, to be fair, Grandpa had only been dead a few months: five months and two weeks to be precise.

It had rained cats and dogs all through the funeral service, so loud you could hardly hear the organ sometimes. I remember some baby began crying and had to be taken out. I sat next to Grandma in the front pew, right beside the coffin. Grandma’s hand was trembling, and when I looked up at her she smiled and squeezed my arm to tell me she was all right. But I knew she wasn’t, so I held her hand. Afterwards we walked down the aisle together behind the coffin, holding on tightly to one another.

Then we were standing under her umbrella by the graveside and watching them lower the coffin, the vicar’s words whipped away by the wind before they could ever be heard. I remember I tried hard to feel sad, but I couldn’t, and not because I didn’t love Grandpa. I did. But he had been ill with multiple sclerosis for ten years or more, and that was most of my life. So I’d never felt I’d known him that well. When I was little he’d sit by my bed and read stories to me. Later I did the same for him. Sometimes it was all he could do to smile. In the end, when he was really bad, Grandma had to do almost everything for him. She even had to interpret what he was trying to say to me because I couldn’t understand any more. In the last few holidays I spent down at Slapton I could see the suffering in his eyes. He hated being the way he was, and he hated me seeing the way he was too. So when I heard he’d died I was sad for Grandma, of course – they’d been married for over forty years. But in a way I was glad it was finished, for her and for him.

After the burial was over we walked back together along the lane to the pub for the wake, Grandma still clutching my hand. I didn’t feel I should say anything to her in case I disturbed her thoughts. So I left her alone.

We were walking under the bridge, the pub already in sight, when she spoke at last. “He’s out of it now, Boowie,” she said, “and out of that wheelchair too. God, how he hated that wheelchair. He’ll be happy again now. You should’ve seen him before, Boowie. You should have known him like I knew him. Strapping great fellow he was, and gentle too, always kind. He tried to stay kind, right to the end. We used to laugh in the early days – how we used to laugh. That was the worst of it in a way; he just stopped laughing a long time ago, when he first got ill. That’s why I always loved having you to stay, Boowie. You reminded me of how he had been when he was young. You were always laughing, just like he used to in the old days, and that made me feel good. It made Grandpa feel good too. I know it did.”

This wasn’t like Grandma at all. Normally with Grandma I was the one who did the talking. She never said much, she just listened. I’d confided in her all my life. I don’t know why, but I found I could always talk to her easily, much more easily than with anyone at home. Back home, people were always busy. Whenever I talked to them I’d feel I was interrupting something. With Grandma I knew I had her total attention. She made me feel I was the only person in the world who mattered to her.

Ever since I could remember I’d been coming down to Slapton for my holidays, mostly on my own. Grandma’s bungalow was more of a home to me than anywhere, because we’d moved house often – too often for my liking. I’d just get used to things, settle down, make a new set of friends and then we’d be off, on the move again. Slapton summers with Grandma were regular and reliable and I loved the sameness of them, and Harley in particular.

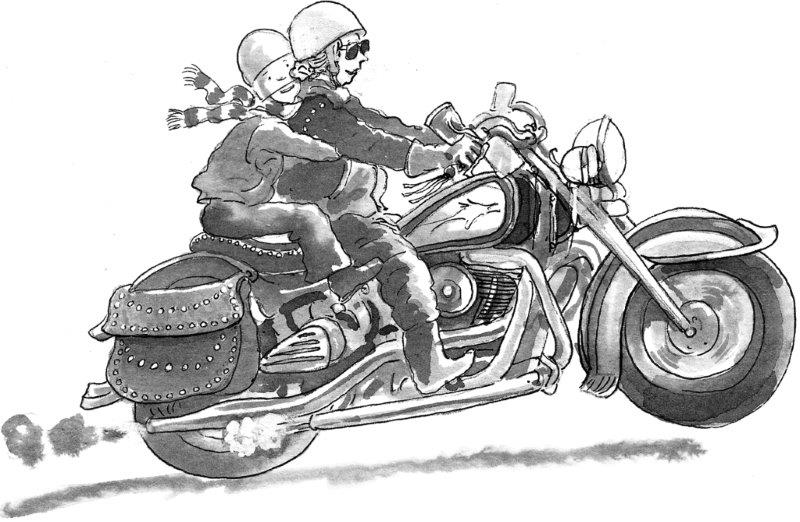

Grandma used to take me out in secret on Grandpa’s beloved motorbike, his pride and joy, an old Harley-Davidson. We called it Harley. Before Grandpa became ill they would go out on Harley whenever they could, which wasn’t often. She told me once those were the happiest times they’d had together. Now that he was too ill to take her out on Harley, she’d take me instead. We’d tell Grandpa all about it, of course, and he liked to hear exactly where we’d been, what field we’d stopped in for our picnic and how fast we’d gone. I’d relive it for him and he loved that. But we never told my family. It was to be our secret, Grandma said, because if anyone back home ever got to know she took me out on Harley they’d never let me come to stay again. She was right too. I had the impression that neither my father (her own son) nor my mother really saw eye to eye with Grandma. They always thought she was a bit stubborn, eccentric, irresponsible even. They’d be sure to think that my going out on Harley with her was far too dangerous. But it wasn’t. I never felt unsafe on Harley, no matter how fast we went. The faster the better. When we got back, breathless with excitement, our faces numb from the wind, she’d always say the same thing: “Supreme, Boowie! Wasn’t that just supreme?”

When we weren’t out on Harley, we’d go on long walks down to the beach and fly kites, and on the way back we’d watch the moorhens and coots and herons on Slapton Ley. We saw a bittern once. “Isn’t that supreme?” Grandma whispered in my ear. Supreme was always her favourite word for anything she loved: for motorbikes or birds or lavender. The house always smelt of lavender. Grandma adored the smell of it, the colour of it. Her soap was always lavender, and there was a sachet in every wardrobe and chest of drawers – to keep moths away, she said.

Best of all, even better than clinging on to Grandma as we whizzed down the deep lanes on Harley, were the wild and windy days when the two of us would stomp noisily along the pebble beach of Slapton Sands, clutching on to one another so we didn’t get blown away. We could never be gone for long though, because of Grandpa. He was happy enough to be left on his own for a while, but only if there was sport on the television. So we would generally go off for our ride on Harley or on one of our walks when there was a cricket match on, or rugby. He liked rugby best. He had been good at it himself when he was younger, very good, Grandma said proudly. He’d even played for Devon from time to time – whenever he could get away from the farm, that is.

Grandma had told me a little about the busy life they’d had before I was born, up on the farm – she’d taken me up there to show me. So I knew how they’d milked a herd of sixty South Devon cows and that Grandpa had gone on working as long as he could. In the end, as his illness took hold and he couldn’t go up and down stairs any more, they’d had to sell up the farm and the animals and move into the bungalow down in Slapton village. Mostly, though, she’d want to talk about me, ask about me, and she really wanted to know, too. Maybe it was because I was her only grandson. She never seemed to judge me either. So there was nothing I didn’t tell her about my life at home or my friends or my worries. She never gave advice, she just listened.

Once, I remember, she told me that whenever I came to stay it made her feel younger. “The older I get,” she said, “the more I want to be young. That’s why I love going out on Harley. And I’m going to go on being young till I drop, no matter what.”

I understood well enough what she meant by “no matter what”. Each time I’d gone down in the last couple of years before Grandpa died she had looked more grey and weary. I would often hear my father pleading with her to have Grandpa put into a nursing home, that she couldn’t go on looking after him on her own any longer. Sometimes the pleading sounded more like bullying to me, and I wished he’d stop. Anyway, Grandma wouldn’t hear of it. She did have a nurse who came in to bath Grandpa each day now, but Grandma had to do the rest all by herself, and she was becoming exhausted. More and more of my walks along the beach were alone nowadays. We couldn’t go out on Harley at all. She couldn’t leave Grandpa even for ten minutes without him fretting, without her worrying about him. But after Grandpa was in bed we would either play Scrabble, which she would let me win sometimes, or we’d talk on late into the night – or rather I would talk and she would listen. Over the years I reckon I must have given Grandma a running commentary on just about my entire life, from the first moment I could speak, all the way through my childhood.

But now, after Grandpa’s funeral, as we walked together down the road to the pub with everyone following behind us, it was her turn to do the talking, and she was talking about herself, talking nineteen to the dozen, as she’d never talked before. Suddenly I was the listener.

The wake in the pub was crowded, and of course everyone wanted to speak to Grandma, so we didn’t get a chance to talk again that day, not alone. I was playing waiter with the tea and coffee, and plates of quiches and cakes. When we left for home that evening Grandma hugged me especially tight, and afterwards she touched my cheek as she’d always done when she was saying good night to me before she switched off the light. She wasn’t crying, not quite. She whispered to me as she held me. “Don’t you worry about me, Boowie dear,” she said. “There’s times it’s good to be on your own. I’ll go for rides on Harley – Harley will help me feel better. I’ll be fine.” So we drove away and left her with the silence of her empty house all around her.

A few weeks later she came to us for Christmas, but she seemed very distant, almost as if she were lost inside herself: there, but not there somehow. I thought she must still be grieving and I knew that was private, so I left her alone and we didn’t talk much. Yet, strangely, she didn’t seem too sad. In fact she looked serene, very calm and still, a dreamy smile on her face, as if she was happy enough to be there, just so long as she didn’t have to join in too much. I’d often find her sitting and gazing into space, remembering a Christmas with Grandpa perhaps, I thought, or maybe a Christmas down on the farm when she was growing up.

On Christmas Day itself, after lunch, she said she wanted to go for a walk. So we went off to the park, just the two of us. We were sitting watching the ducks on the pond when she told me. “I’m going away, Boowie,” she said. “It’ll be in the New Year, just for a while.”

“Where to?” I asked her.

“I’ll tell you when I get there,” she replied. “Promise. I’ll send you a letter.”

She wouldn’t tell me any more no matter how much I badgered her. We took her to the station a couple of days later and waved her off. Then there was silence. No letter, no postcard, no phone call. A week went by. A fortnight. No one else seemed to be that concerned about her, but I was. We all knew she’d gone travelling, she’d made no secret of it, although she’d told no one where she was going. But she had promised to write to me and nothing had come. Grandma never broke her promises. Never. Something had gone wrong, I was sure of it.

Then one Saturday morning I picked up the post from the front door mat. There was one for me. I recognised her handwriting at once. The envelope was quite heavy too. Everyone else was soon busy reading their own post, but I wanted to open Grandma’s envelope in private. So I ran upstairs to my room, sat on the bed and opened it. I pulled out what looked more like a manuscript than a letter, about thirty or forty pages long at least, closely typed. On the cover page she had sellotaped a black and white photograph (more brown and white really) of a small girl who looked a lot like me, smiling toothily into the camera and cradling a large black and white cat in her arms. There was a title: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, with her name underneath, Lily Tregenza. Attached to the manuscript by a large multicoloured paperclip was this letter.

Dearest Boowie,

This is the only way I could think of to explain to you properly why I’ve done what I’ve done. I’ll have told you some of this already over the years, but now I want you to know the whole story. Some people will think I’m mad, perhaps most people—I don’t mind that. But you won’t think I’m mad, not when you’ve read this. You’ll understand, I know you will. That’s why I particularly wanted you to read it first. You can show it to everyone else afterwards. I’ll phone soon…when you’re over the surprise.

When I was about your age—and by the way that’s me on the front cover with Tips—I used to keep a diary. I was an only child, so I’d talk to myself in my diary. It was company for me, almost like a friend. So what you’ll be reading is the story of my life as it happened, beginning in the autumn of 1943, during the Second World War, when I was growing up on the family farm. I’ll be honest with you, I’ve done quite a lot of editing. I’ve left bits out here and there because some of it was too private or too boring or too long. I used to write pages and pages sometimes, just talking to myself, rambling on.

The surprise comes right at the very end. So don’t cheat, Boowie. Don’t look at the end. Let it be a surprise for you—as it still is for me.

Lots of love,

Grandma

PS Harley must be feeling very lonely all on his own in the garage. We’ll go for a ride as soon as I get back; as soon as you come to visit. Promise.

Friday, September 10th 1943

I’ve been back at school a whole week now. When Miss McAllister left at the end of last term I was cock-a-hoop (I like that word), we all were. She was a witch, I’m sure she was. I thought everything would be tickety-boo (I like that word too) just perfect, and I was so much looking forward to school without her. And who do we get as a head teacher instead? Mrs “Bloomers” Blumfeld. She’s all smiles on the outside, but underneath she’s an even worser witch than Miss McAllister. I know I’m not supposed to say worser but it sounds worser than worse, so I’m using it. So there. We call her Bloomers because of her name of course, and also because she came into class once with her skirt hitched up by mistake in her navy-blue bloomers.

Today Bloomers gave me a detention just because my hands were dirty again. “Lily Tregenza, I think you are one of the most untidiest girls I have ever known.” She can’t even say her words properly. She says zink instead of think and de instead of the. She can’t even speak English properly and she’s supposed to be our teacher. So I said it wasn’t fair, and she gave me another detention. I hate her accent; she could be German. Maybe she’s a spy! She looks like a spy. I hate her, I really do. And what’s more, she favours the townies, the evacuees. That’s because she’s come down from London like they have. She told us so.

We’ve got three more townies in my class this term, all from London like the others. There’s so many of them now there’s hardly enough room to play in the playground. There’s almost as many of them as there are of us. They’re always fighting too. Most of them are all right, I suppose, except that they talk funny. I can’t understand half of what they say. And they stick together too much. They look at us sometimes like we’ve got measles or mumps or something, like they think we’re all stupid country bumpkins, which we’re not.

One of the new ones – Barry Turner he’s called – is living in Mrs Morwhenna’s house, next to the shop. He’s got red hair everywhere, even red eyebrows. And he picks his nose which is disgusting. He gets lots more spellings wrong than me, but Bloomers never gives him a detention. I know why too. It’s because Barry’s dad was killed in the airforce at Dunkirk. My dad’s away in the army, and he’s alive. So just because he’s not dead, I get a detention. Is that fair? Barry told Maisie, who sits next to me in class now and who’s my best friend sometimes, that she could kiss him if she wanted to. He’s only been at our school a week. Cheeky monkey. Maisie said she let him because he’s young – he’s only ten – and because she was sorry for him, on account of his dad, and also because she wanted to find out if townies were any good at it. She said it was a bit sticky but all right. I don’t do kissing. I don’t see the point of it, not if it’s sticky.

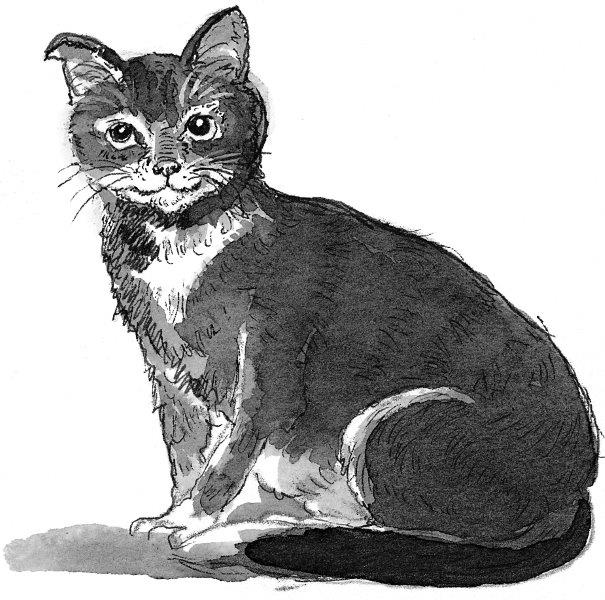

Tips is going to have her kittens any day now. She’s all saggy baggy underneath. Last time she had them on my bed. She’s the best cat (and the biggest) in the whole wide world and I love her more than anyone or anything. But she keeps having kittens, and I wish she wouldn’t because we can’t ever keep them. No one wants them because everyone’s got cats of their own already, and they all have kittens too.

It was all because of Tips and her kittens that I had my row with Dad, the biggest row of my life, when he was last home on leave from the army. He did it when I was at school, without even telling me. As soon as they were born he took all her kittens out and drowned them just like that. When I found out I said terrible things to him, like I would never ever speak to him again and how I hoped the Germans would kill him. I was horrible to him. I never made it up with him either. I wrote him a letter saying I was sorry, but he hasn’t replied and I wish he would. He probably hates me now, and I wouldn’t blame him. If anything happened to him I couldn’t bear it, not after what I said.

Mum keeps telling me I shouldn’t let my tongue do my thinking for me, and I’m not quite sure what that means. She’s just come in to say good night and blow out my lamp. She says I spend too much time writing my diary. She thinks I can’t write in the dark, but I can. My writing may look a bit wonky in the morning, but I don’t care.

Sunday, September 12th 1943

We saw some American soldiers in Slapton today; it’s the first time I’ve ever seen them. Everyone calls them Yanks, I don’t know why. Grandfather doesn’t like them, but I do. I think they’ve got smarter uniforms than ours and they look bigger somehow. They smiled a lot and waved – particularly at Mum, but that was just because she’s pretty, I could tell. When they whistled she went very red, but she liked it. They don’t say “hello”, they say “hi” instead, and one of them said “howdy”. He was the one who gave me a sweet, only he called it “candy”. I’m sucking it now as I’m writing. It’s nice, but not as nice as lemon sherberts or peppermint humbugs with the stripes and chewy centres. Humbugs are my best favourites, but I’m only allowed two a week now because of rationing. Mum says we’re really lucky living on the farm because we can grow our own vegetables, make our own milk and butter and cream and eat our own chickens. So when I complain about sweet rationing, which I do, she always gives me a little lecture on how lucky we are. Barry says they’ve got rationing for everything in London, so maybe Mum is right. Maybe we are lucky. But I still don’t see how me having less peppermint humbugs is going to help us win the war.