Полная версия:

Favourite Cat Stories: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, Kaspar and The Butterfly Lion

Thursday, September 16th 1943

Mum got a letter from Dad today. Whenever she gets a letter she’s very happy and sad at the same time. She says he’s out in the desert in Africa with the Eighth Army and he’s making sure the lorries and the tanks work – he’s very good at engines, my dad. It’s very hot in the daytime, he says, but at night it’s cold enough to freeze your toes off. Mum let me read the letter after she had. He didn’t say anything about Tips and the kittens or the row we had. Maybe he’s forgotten all about it. I hope so.

I feel bad about writing this, but I must write what I really feel. What’s the point in writing at all otherwise? The truth is, I don’t really miss Dad like I know I should, like I know Mum does. When I’m actually reading his letters I miss him lots, but then later on I forget all about him unless someone talks about him, unless I see his photo maybe. Perhaps it’s because I’m still cross with him about the kittens. But it’s not just because of the kittens that I’m cross with him. The thing is, he didn’t need to go to fight in the war; he could have stayed with us and helped Grandfather and Mum on the farm. Other farmers were allowed to stay. He could have. But he didn’t. He tried to explain it to me before he joined up. He said he wouldn’t feel right about staying home when there were so many men going off to the war, men the same age as he was. I told him he should think of Grandfather and Mum and me, but he wouldn’t listen. They’ve got to do all the work on their own now, all the milking and the muck spreading, all the haymaking and the lambing. Dad was the only one who could fix his Fordson tractor and the thresher, and now he’s not here to do it. I help out a bit, but I’m not much use. I’m only twelve (almost anyway) and I’m off to school most days. He should be here with us, that’s what I think. I’m fed up with him being away. I’m fed up with this war. We’re not allowed down on the beach any more to fly our kites. There’s barbed wire all around it to keep us off, and there’s mines buried all over it. They’ve put horrible signs up everywhere warning us off. That wasn’t much use to Farmer Jeffrey’s smelly old one-eyed sheepdog that lifted his leg on everything he passed (including my leg once). He wandered on to the beach under the wire yesterday and blew himself up. Poor old thing.

I had this idea at school (probably because Bloomers was reading us the King Arthur stories). I think we should dress Churchill and Hitler up in armour like King Arthur’s knights, stick them on horses, give them a lance each and let them sort it out between them. Whoever is knocked off loses, and the war would be over and we could all go back to being normal again. Churchill would win of course, because Hitler looks too weak and feeble even to sit on a horse, let alone hold a lance. So we would win. No more rationing. All the humbugs I want. Dad could come home and everything would be like it was before. Everything would be tickety-boo.

Friday, September 17th 1943

I saw a fox this morning running across south field with a hen in his mouth. When I shouted at him, he stopped and looked at me for a moment as if he was telling me to mind my own business. Then he just trotted off, cool as you like, without a care in the world. Mum says it wasn’t one of her hens, but she was someone’s hen, wasn’t she? Someone should tell that fox about rationing. That’s what I think.

There’s lots of daddy-longlegs crawling up my window, and a butterfly. I’ll just let them out…

It’s still light outside. I love light evenings. It was a red admiral butterfly. Beautiful. Supreme.

Mum and Grandfather are having an argument downstairs, I can hear them. Grandfather is going on about the American soldiers again, “ruddy Yanks” he calls them. He says they’re all over the place, hundreds of them, and walking about as if they own the place, smoking cigars, chewing gum. Like an invasion, he says. Mum speaks more quietly than Grandfather, so it’s difficult to hear what she’s saying.

They’ve stopped arguing now. They’ve got the radio on instead. I don’t know why they bother. The news of the war is always bad, and it only makes them feel miserable. It’s hardly ever off, that radio.

Monday, September 20th 1943

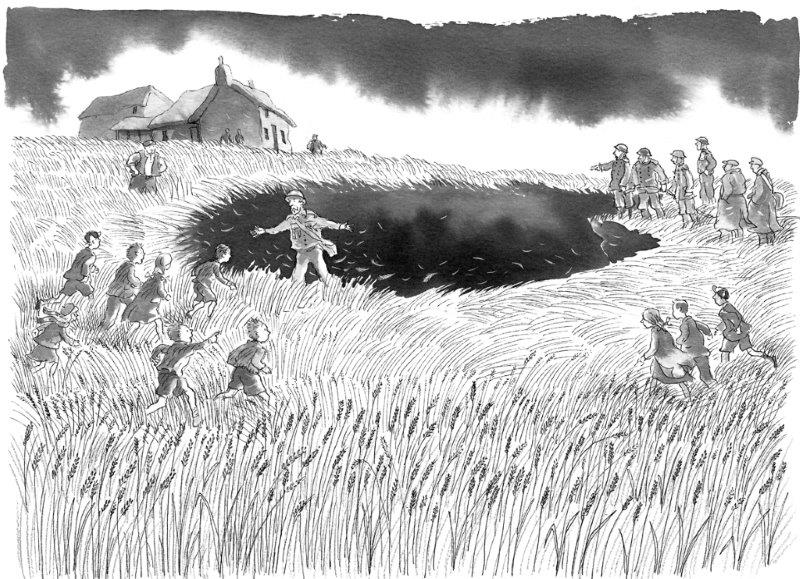

Two big surprises. One good, one bad. We were all sent home from school today. That was the good one. It was all because of Mr Adolf Ruddy Hitler, as Grandfather calls him. So thanks for the holiday, Mr Adolf Ruddy Hitler. We were sitting doing arithmetic with Bloomers – long division which I can’t understand no matter how hard I try – when we heard the roaring and rumbling of an aeroplane overhead, getting louder and louder, and the classroom windows started to rattle. Then there was this huge explosion and the whole school shook. We all got down on the floor and crawled under the desks like we have to do in air-raid practice, except this was very much more exciting because it was real. By the time Bloomers had got us out into the playground the German bomber was already far out over the sea. We could see the black crosses on its wings. Barry pretended he was firing an ack-ack gun and tried to shoot it down. Most of the boys joined in, making their silly machine-gun noises – dadadadadada.

Bloomers sent us home just in case there were more bombers on the way. But we didn’t go home. Instead we all went off to see if we could find where the bomb had landed. We found it too. There was a massive hole in Mr Berry’s cornfield just outside the village. The Home Guard was there already, Uncle George in his uniform telling them all what to do. They were making sure no one fell in, I suppose. No one had been hurt, except a poor old pigeon who was probably having a good feed of corn when the bomb fell. His feathers were everywhere. Then one of the townies got all hoity-toity about it and said he’d seen much bigger holes than this one back home, in London. Big Ned Simmons told him just where he could go and just what he thought of him and all the snotty-nosed townies, and it all got a bit nasty after that, us against them. So I walked away.

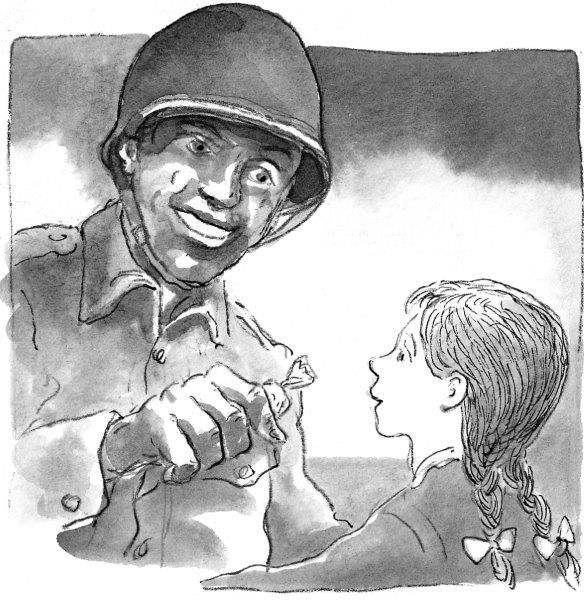

I was on my way home afterwards when I saw this jeep coming down the lane towards me. There was one soldier in it. He had an American helmet on. He screeched to a stop and said, “Hi there!” He was a black man. I’ve never in my life seen a black person before, only in pictures in books, so I didn’t quite know what to say. I kept trying not to stare, but I couldn’t help myself. He had to ask me twice if he was on the right road to Torpoint before I even managed a nod. “You know something? You got pigtails just like my littlest sister.” Then he said, “See ya!” and off he went, splashing through the puddles. I was a bit disappointed not to get any candy.

When I got home I had my other surprise, my bad one. I told them about the bomb and about Uncle George and the Home Guard being there, and I told them about the black soldier I’d met in the lane. They didn’t seem very interested in any of it. I thought that was strange. And it was strange too that neither of them seemed to want to talk to me much or even to look at me. We were all having tea in the kitchen when Tips came in. She rubbed herself against my leg and then went off mewing under the table, under the dresser, into the pantry. But she wasn’t mewing like she does when she’s after food or love, or when she brings in a mouse. She was calling, and when I picked her up she felt different. Still saggy baggy underneath, but definitely different. She wasn’t full and fat any more. I knew what they’d done at once.

“We had to do it, Lily,” Mum said. “It’s better straight away, before she gets too fond of them. Sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind.”

I screamed at them: “Murderers! Murderers!” Then I brought Tips up to my room. I’m still up here with her now. I’ve been crying ever since, and really loudly too so they can hear me, so they’ll feel really bad, as bad as I do.

Tips is lying in my lap and washing herself just like nothing’s happened. She’s even purring. Maybe she doesn’t know yet. Or maybe she does and she’s forgiven us already. Now she’s stopped licking herself. She’s looking at me as if she knows. I don’t think she has forgiven us. I don’t think she’ll ever forgive us. Why should she?

Tuesday, October 5th 1943

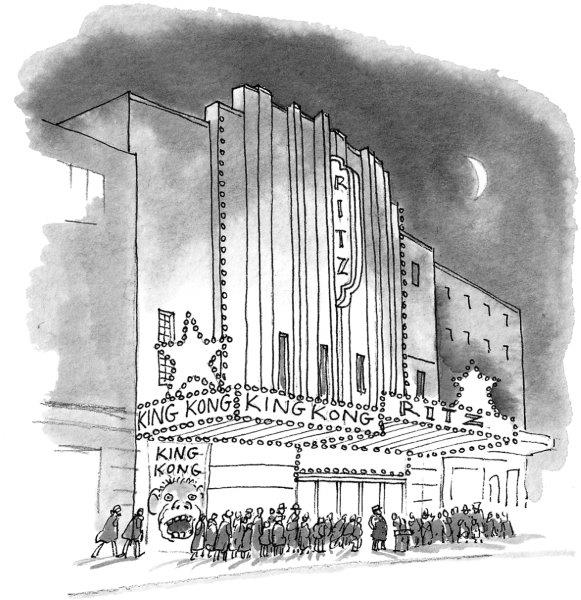

My birthday. I was born twelve years ago today at ten o’clock in the morning. I’ve been calling myself twelve for a long time, and now I really am. All I want to be now is thirteen. And even thirteen isn’t old enough. I so much want to be much older than I am, but not old like Grandfather so that I walk bent and my hands are all hard and wrinkly and veiny. I don’t want a drippy nose and hairs growing out of my ears. But I do want the years to hurry on by until I’m about seventeen, so school and Bloomers and long division are over and done with, so that no one can take my kittens away and drown them. It’ll be so good when I’m seventeen, because the war will be over by then, that’s for sure. Grandfather says that we’re already winning and so it can’t be long till it’s finished. Then I can go up to London on the train – I’ve never been on a train – and I can see the shops and ride on those big red buses and go on the underground. Barry Turner’s told me all about it. He says there’s lights in the streets, millions of people everywhere, and cinemas and dance halls. His dad used to work in a cinema before the war, before he was killed. He told me that one day. That was the first thing he’s ever told me about his dad.

Which reminds me: I still haven’t had a letter from my dad. I think he’s still cross with me after what I said. I wish, I wish I hadn’t said it. I had a dream about him the other night. I don’t usually remember my dreams at all, but I remember this one, some of it anyway. He was back at home milking cows again, but he was in uniform with his tin helmet on. It was scary because, when I came into the milking parlour, I spoke to him and he never looked up. I shouted but he still never looked at me. It was like one of us wasn’t there, but we were. We both were.

Monday, November 1st 1943

“Pinch, punch, first day of the month. Slap and a kick for being so quick. Punch in the eye for being so sly.” Barry kept saying it to me every time he saw me. It was really annoying. In the end I shouted at him and hurt his feelings. I know I shouldn’t have, he was only trying to be friendly. He didn’t cry but he nearly did.

But tonight I feel worse about something else, something much worse. Ever since Bloomers came I’ve been giving her a hard time, we all have, but me most of all. I’m really good at giving people a hard time when I want to. I cheeked her when she first came because I didn’t like her and she got ratty and punished me. So I cheeked her again and she punished me again and on it went, and after that I could never get on with her at all. I’ve been mean to her ever since I’ve known her, and now this has happened.

The vicar came into school today and told us he’d be teaching us for the morning because Mrs Blumfeld wasn’t feeling very well. She wasn’t ill so much as sad, he said, sad because she had just heard the news that her husband, who is in the merchant navy, had been lost at sea in the Atlantic. His ship had been torpedoed. They’d picked up a few survivors, but Mrs Blumfeld’s husband wasn’t one of them. The vicar told us that when she came back into school we had to be very good and kind, so as not to upset her. Then he said we should close our eyes and hold our hands together and pray for her. I did pray for her too, but I also prayed for myself, because I don’t want God to have his own back on me for all the horrible things I’ve said and thought about her. I prayed for my dad too, that God wouldn’t make him die in the desert just because I’d been mean to Mrs Blumfeld, that I hadn’t meant it when I’d said I wanted him to die because he drowned the kittens. I’ve never prayed so hard in my life. Usually my mind wanders when I’m supposed to be praying, but it didn’t today.

After lunch Mrs Blumfeld came into school. She had no lipstick on. She looked so pale and cold. She was trembling a little too. We left a letter for her on her desk which we had all signed, to say how sorry we all were about her husband. She looked very calm, as if she was in a daze. She wasn’t crying or anything, not until she read our letter. Then she tried to smile at us through her tears and said it was very thoughtful of us, which it wasn’t because it was the vicar’s idea, but we didn’t tell her that. We all went around whispering and being extra good and quiet all day. I feel so bad for her now because she’s all alone. I won’t call her Bloomers ever again. I don’t think anyone will.

Monday, November 8th 1943

Ever since Mrs Blumfeld’s husband was killed, I’ve been worrying a lot about Dad. I didn’t before, but I am now, all the time. I keep thinking of him lying dead in the sand of Africa. I try not to, but the picture of him lying there keeps coming into my head. And it’s silly, I know it is, because I got a letter from him only yesterday, at last, and he’s fine. (His letters take for ever to come. This one was dated two months ago.) He never said anything about me being cross. In fact he sent his love to Tips. Dad says it’s so hot out in the desert he could almost fry an egg on the bonnet of his jeep. He says he longs for a few days of good old Devon drizzle, and mud. He really misses mud. How can you miss mud? We’re all sick of mud. It’s been raining here for days now: mizzly, drizzly, horrible rain. Today it was blowing in from the sea, so I was wet through by the time I got home from school.

Grandfather came in later. He’d been drinking a bit, but then he always drinks a bit when he goes to market, just to keep the cold out, he says. He sat down in front of the stove and put his feet in the bottom oven to warm up. Mum hates him doing it but he does it all the same. He’s got holes in his socks too. He always has.

“There’s hundreds of gum-chewing Yanks everywhere in town,” he said. “Like flies on a ruddy cow clap.” I like it when Grandfather talks like that. He got a dirty look from Mum, but he didn’t mind. He just gave me a big wink and a wicked grin and went on talking. He said he was sure something’s going on: there are fuel dumps everywhere you look, tents going up all over the place, tanks and lorries parked everywhere. “It’s something big,” he said. “I’m telling you.”

Still raining out there. It’s lashing the windowpanes as I’m writing, and the whole house is creaking and shaking, almost as if it’s getting ready to take off and fly out over the sea. I can hear the cows lowing in the barn. They’re scared. Tips is frightened silly too. She wants to hide. She keeps jogging my writing. She’s trying to push her head deeper and deeper into my armpit. I’m not frightened, I like storms. I like it when the sea comes thundering in and the wind blows so hard that it takes your breath away.

Mrs Blumfeld said something this morning that took my breath away too. That Daisy Simmons, Ned’s little sister, is always asking questions when she shouldn’t and today she put her hand up and asked Mrs Blumfeld if she was a mummy, just like that! Mrs Blumfeld didn’t seem to mind at all. She thought for a bit, then she said that she would never have any children of her own because she didn’t need them; she had all of us instead. We were her family now. And she had her cats, which she loved. I didn’t know she had cats. I was watching her when she said it and you could see she really did love them. I was so wrong about her. She likes cats so she must be nice. I’m going to sleep now and I’m not going to think of Dad lying out in the desert. I’m going to think of Mrs Blumfeld at home with her cats instead.

I just went to shut the window, and I saw a barn owl flying across the farmyard, white and silent in the darkness. There one moment, gone the next. A ghost owl. He’s screeching now. They screech, they don’t toowit-toowoo. That word looks really funny when you write it down, but owls don’t have to write it down, do they? They just have to hoot it, or toowit-toowoo it.

Saturday, November 13th 1943

Today was a day that will change my life for ever. Grandfather was right when he said something was up. And it is something big too, something very big – I have to keep pinching myself to believe it’s true, that it’s really going to happen. Yesterday was just like any other day. Rain. School. Long division. Spelling test. Barry picking his nose. Barry smiling at me from across the classroom with his big round eyes. I just wish he wouldn’t smile at me so. He’s always so smiley.

Then today it happened. I knew all day there was going to be some kind of meeting in the church in the evening, that someone from every house had to go and it was important. I knew that, because Mum and Grandfather were arguing about it over breakfast before I went off to school. Grandfather was being a grumpy old goat. He’s been getting crotchety a lot just lately. (Mum says it’s because of his rheumatism – it gets worse in damp weather.) He kept saying he had too much to do on the farm to be bothered with meetings and such. And besides, he said, women were better at talking because they did more of it. Of course that made Mum really mad, so they had a fair old dingdong about it. Anyway in the end Mum gave in and said she’d go, and she asked me to go along with her for company. I didn’t want to go but now I’m glad I did, really glad.

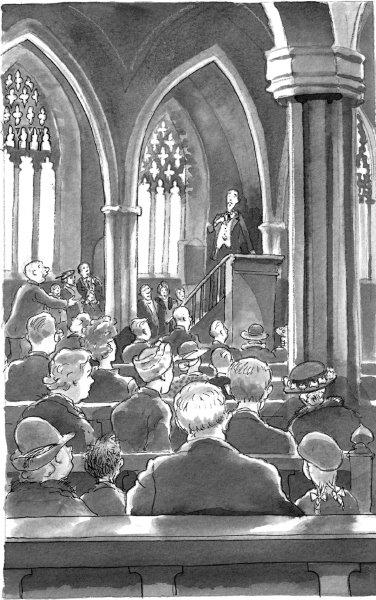

The place was packed out. There was standing room only by the time we got there. Then this bigwig, Lord Somethingorother, got up and started talking. I didn’t pay much attention at first because he had this droning-on hoity-toity (I like that word) sort of voice that almost put me to sleep. But suddenly I felt a strange stillness and silence all around me. It was almost as if everyone had stopped breathing. Everyone was listening, so I listened too. I can’t remember his exact words, but I think it went something like this.

“I know it’s asking a lot of you,” the bigwig was saying, “but I promise we wouldn’t be asking you if we didn’t have to, if it wasn’t absolutely necessary. They’ll be needing the beach at Slapton Sands and the whole area behind it, including this village. They need it because they have to practise landings from the sea for the invasion of France when it comes. That’s all I can tell you. Everything else is top secret. No point in asking me anything about it, because I don’t know any more than you do. What I do know is that you have seven weeks from today to move out, lock, stock and barrel – and I mean that. You have to take everything with you: furniture, food, coal, all your animals, farm machinery, fuel, and all fodder and crops that can be carried. Nothing you value must be left behind. After the seven weeks is up, no one will be allowed back – and I mean no one. There’ll be a barbed-wire perimeter fence and guards everywhere to keep you out. Besides which, it will be dangerous. There’ll be live firing going on: real shells, real bullets. I know it’s hard, but don’t imagine it’s just Slapton, that you’re the only ones. Torcross, East Allington, Stokenham, Sherford, Chillington, Strete, Blackawton: 3000 people have got to move out; 750 families, 30,000 acres of land have got to be cleared in seven weeks.”

Some people tried to stand up and ask questions, but it was no use. He just waved them down.

“I’ve told you. It’s no good asking me the whys and wherefores. All I know is what I’ve told you. They need it for the war effort, for training purposes. That’s all you need to know.”

“Yes, but for how long?” asked the vicar from the back of the hall.

“About six months, nine months, maybe longer. We can’t be sure. And don’t worry. We’ll make sure everyone has a place to live, and of course there’ll be proper compensation paid to everyone, to all the farms and businesses for any loss or damage. And I have to be honest with you here, I have to warn you that there will be damage, lots of it.”

You could have heard a pin drop. I was expecting lots of protests and questions, but everyone seemed to be struck dumb. I looked up at Mum. She was staring ahead of her, her mouth half open, her face pale. All the way home in the dark, I kept asking her questions, but she never said a word till we reached the farmyard.

“It’ll kill him,” she whispered. “Your grandfather. It’ll kill him.”

Once back home she came straight out with it. Grandfather was in his chair warming his toes in the oven as usual. “We’ve got to clear out,” she said, and she told him the whole thing. Grandfather was silent for a moment or two. Then he just said, “They’ll have to carry me out first. I was born here and I’ll die here. I’m not moving, not for they ruddy Yanks, not for no one.” Mum’s still downstairs with him, trying to persuade him. But he won’t listen. I know he won’t. Grandfather doesn’t say all that much, but what he says he means. What he says, he sticks to. Tips has jumped up on my bed and walked all over my diary with her muddy paws! She’s lucky I love her as much as I do.

Tuesday, November 16th 1943

At school, in the village, no matter where you go or whoever you meet, it’s all anyone talks about: the evacuation. It’s like a sudden curse has come down on us all. No one smiles. No one’s the same. There’s been a thick fog ever since we were told. It hangs all around us, tries to come in at the windows. It makes me wonder if it’ll ever go away, if we’ll ever see the sun again.

I’ve changed my mind completely about Barry. That skunkhead Bob Bolan came up to me at playtime and started on about Grandfather, just because he’s the only one in the village refusing to go. He said he was a stupid old duffer. He said he should be sent away to a lunatic asylum and locked up. Maisie was there with me and she never stood up for me, and I thought she was supposed to be my best friend. Well she’s not, not any more. No one stood up for me, so I had to stand up for myself. I pushed Skunkhead (I won’t call him Bob any more because Skunkhead suits him better) and Skunkhead pushed me, and I fell over and grazed my elbow. I was sitting there, picking the grit out of my skin and trying not to let them see I was crying, when Barry came up. The next thing I know he’s got Skunkhead on the ground and he’s punching him. Mrs Blumfeld had to pull him off, but not before Skunkhead got a bleeding nose, which served him right. As she took them both back into school Barry looked over his shoulder and smiled. I never got a chance to say thank you, but I will. If only he’d stop picking his nose and smiling at me I think I could really like him a lot. But I’m not doing kissing with him.

Tuesday, November 30th 1943

Some people have started moving their things out already. This morning I saw Maisie’s dad going up the road with a cartload of beds and chairs, cupboards, tea chests and all sorts. Maisie was sitting on the top and waving at me. She’s my friend again, but not my best friend. I think Barry’s my best friend now because I know I can really trust him. Then I saw Miss Langley driving off in a car with lots of cases and trunks strapped on top. She had Jimbo on her lap, her horrible Jack Russell dog who chases Tips up trees whenever he sees her. Mum told me that Miss Langley is off to stay with a cousin up in Scotland, hundreds of miles away. I’ve just told Tips and suddenly she’s purring very happily. It’s a “good riddance” purr, I think.