Полная версия:

Favourite Cat Stories: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, Kaspar and The Butterfly Lion

A lot of people are going to stay with relatives, and we could too except that Grandfather won’t hear of it. Uncle George farms only a couple of miles away, just beyond where the wire fence will be. They’re beginning to put it up already. He said that family’s family, and he’d be only too happy to help us out. I heard him telling Grandfather. We could take our milking cows up to his place, all our sheep, all the farm machinery, Dad’s Fordson tractor, everything. It’ll be a tight squeeze, Uncle George said, but we could manage. Grandfather won’t listen. He won’t leave, and that’s that.

Wednesday, December 1st 1943

At playtime I found Barry sitting on his own on the dustbins behind the bike shed. He was all red around the eyes. He’d been crying, but he was trying not to show it. He wouldn’t tell me why at first, but after a while I got it out of him. It’s because there won’t be room for him any more with Mrs Morwhenna when she moves into Kingsbridge next week. He likes her a lot and now he has nowhere to go. So, to make him feel better, and because of what he had done for me the other day with Skunkhead, I said he could come home with me and play after school, so long as he didn’t pick his nose. He perked up after that, and he was even chirpier when he saw the cows and the sheep. And when he saw Dad’s Fordson tractor he went loopy. It was like he’d been given a new toy of his own to play with. I couldn’t get him off it. Grandfather took him off around the farm, letting him steer the tractor – which wasn’t fair because he’s never let me do that.

By the time they came back they were both of them as happy as larks. I haven’t heard Grandfather laugh so much in ages. Barry tucked into Mum’s cream sponge cake, slice after slice of it, and all the time he never stopped talking about the tractor and the farm (and no one told him not to talk with his mouth full, which wasn’t fair either because Mum’s always ticking me off for that). He’d have scoffed the lot if Mum hadn’t taken it away. He still smiles at me, but I don’t mind so much now. In fact I quite like it really.

Afterwards, when we were walking together down the lane to the farm gate, he seemed suddenly down in the dumps. He hardly said a word all the way. Then suddenly he just blurted it out. “I could come and stay,” he said. “I wouldn’t be a nuisance, honest. I wouldn’t pick my nose, honest.” I couldn’t say no, but I didn’t want to say yes, not exactly. I mean, it would be like having a brother in the house. I’d never had a brother and I wasn’t sure I wanted one, even if Barry was my best friend now, sort of. So I said maybe. I said I’d ask. And I did, at supper time. Grandfather didn’t even have to think about it. “The lad needs a home, doesn’t he?” he said. “We’ve got a home. He needs feeding. We’ve got food. We should have had one of those evacuee children before, but I never liked townies much till now. This one’s all right though. He’s a good lad. Besides, it’ll be good to have a boy about the place. Be like the old days, when your father was a boy. You tell him he can come.”

He never asked me what I thought, never asked Mum. He just said yes. It took me so much by surprise that I wasn’t ready for it, and neither was Mum. So it looks as if I’m going to have a sort of brother living with us, whether I like it or not. Mum came in a minute ago and sat on my bed. “Do you mind about Barry?” she asked me.

“He’s all right, I suppose,” I told her. And he is too, except when he’s picking his nose of course.

“One thing’s for sure, it’ll make Grandfather happier,” Mum said. “And if he’s happier, then maybe it’ll be easier to talk him into leaving, into moving to Uncle George’s place. They’re going to move us out, you know, Lily. One way or another, they’re going to do it.” She gave me a good long cuddle tonight. She hasn’t done that for ages. I think she thinks I’m too old for it or something, but I’m not.

I haven’t had my nightmare about Dad for a long time now, which is good. But I haven’t thought much about him either, which is not so good.

Wednesday, December 15th 1943

Barry moved in this afternoon. He walked home with me from school carrying his suitcase. He skipped most of the way. He’s sleeping in the room at the end of the passage. Grandfather says that’s where Dad always used to sleep when he was a boy. Straight after tea Grandfather took him out to feed the cows. From the look on Barry’s face when he came back I’m sure he thinks he’s in heaven. Like he says, there’s no tractors in London, no cows, no sheep, no pigs. He’s already decided he likes the sheep best. And he likes mud too, and he likes rolling down hills and getting his coat covered in sheep poo. He told Mum that brown’s his favourite colour because he likes mud, and sausages. I learnt a little bit more about him today – he tells Mum more than he tells me. But I listen. He didn’t say much about his dad of course, but his mum works on the buses in London, a “clippy”, he says – that’s someone who sells the tickets. That’s about all I know about him so far, except that he twiddles his hair when he’s upset and he doesn’t like cats because they smile at him. He’s a good one to talk. He’s always smiling at me. If he’s living with us, he’d better be nice to Tips, that’s all I can say. He twiddles his hair a lot at school. I’ve noticed it in class, especially when he’s doing his writing. He can’t do his handwriting very well. Mrs Blumfeld tries to help him with his letters and his spelling but he still keeps getting everything back to front. (I think he’s frightened of them – of letters, I mean.) He’s good with numbers though. He doesn’t have to use his fingers at all. He does it all in his head, which I can’t do.

Grandfather’s still telling everyone he’s not going to be moved out. Lots of people have had a go at persuading him, the vicar, Doctor Morrison, even Major Tucker came to see us from the Manor House. But Grandfather won’t budge. He just carries on as if nothing is happening. Half the village has moved out now, including Farmer Gent next door. I saw the last of his machinery being taken away yesterday. All his animals have gone already. They went to market last week. His farmhouse is empty. Usually I can see a light or two on in there from my window, but not any more. It’s dark now, pitch black. It’s like the house has gone too.

We see more and more American soldiers and lorries coming into the village every day. Grandfather’s turning a blind eye to all of it. Barry’s out with him now. They’ve gone milking. I saw them go off together a while ago, stomping across the yard in their wellies. Barry looked like he’d been doing it all his life, as if he’d always lived here, as if he was Grandfather’s grandson. To tell the truth I feel a little jealous. No, that’s not really true. I feel a lot jealous. I’ve often thought Grandfather wanted me to be a boy. Now I’m sure of it.

Thursday, December 16th 1943

When school ends tomorrow it’ll be the end of term and that’s four days earlier than we thought. We’ve got four days’ extra holiday. Hooray! Yippee! That’s because they’ve got to move out all the desks, the blackboard, the bookshelves, everything, down to the last piece of chalk. Mrs Blumfeld told us the American soldiers will be coming tomorrow to help us move out. We’ll be going to school in Kingsbridge after Christmas. There’ll be a bus to take us in because it’s too far to walk. And Mrs Blumfeld said today that she’ll go on being our teacher there. We all cheered and we meant it too. She’s the best teacher I’ve ever had, only sometimes I still don’t exactly understand her because of how she speaks. Because she’s from Holland we’ve got lots of pictures of Amsterdam on the wall. They’ve got canals instead of roads there. She’s put up two big paintings, both by Dutchmen, one of an old lady in a hat by a painter called Rembrandt (that’s funny spelling, but it’s right), and one of colourful ships on a beach by someone else. I can’t remember his name, I think it’s Van something or other. I was looking at that one today while we were practising carols. We were singing I Saw Three Ships Come Sailing In, and there they were up on the wall, all these ships. Funny that. I don’t really understand that carol. What’s three ships sailing in got to do with the birth of Jesus? I like the tune though. I’m humming it now as I write.

We all think she’s very brave to go on teaching us like she has after her husband was drowned. Everyone else in the village likes her now. She’s always out cycling in her blue headscarf, ringing her bell and waving whenever she sees us. I hope she doesn’t remember how mean I was to her when she first came. I don’t think she can do because she chose me to sing a solo in the carol concert, the first verse of In the Bleak Midwinter. I practise all the time: on the way home, out in the fields, in the bath. Barry says it sounds really good, which is nice of him. And he doesn’t pick his nose at all any more, nor smile at me all the time. Maybe he knows he doesn’t need to smile at me – maybe he knows I like him. My singing sounds really good in the bath, I know it does. But I can’t take the bath into church, can I?

Saturday, December 18th 1943

I love Christmas carols, especially In the Bleak Midwinter. I wish we didn’t only sing them at Christmas time. We had our carol concert this afternoon in the church and I had to sing my verse in front of everyone. I wobbled a bit on one or two notes, but that’s because I was trembling all over, like a leaf, just before I did it. Barry told me it sounded perfect, but I knew he said that just to make me happy. And it did, but then I thought about it. The thing is that Barry can sing only on one note, so he wouldn’t really know if it sounded good or bad, would he?

There’s only a fortnight to go now before we’re supposed to leave. Barry keeps asking me what will happen to Grandfather if he doesn’t move out. He’s frightened they’ll take him off to prison. That’s because we had a visit yesterday from the army and the police telling Grandfather he had to pack up and go, or he’d be in real trouble. Grandfather saw them off good and proper, but they said they’ll be back. I just wish Barry wouldn’t keep asking me about what’s going to happen, because I don’t know, do I? No one does. Maybe they will put him in prison. Maybe they’ll put us all in prison. It makes me very frightened every time I think about it. So I’ll try not to. If I do think about it, then I’ll just have to make myself worry about something else. This evening Barry and me were sitting at the top of the staircase in our dressing gowns listening to Mum and Grandfather arguing about it again down in the kitchen. Grandfather sounded more angry than I’ve ever heard him. He said he’d rather shoot himself than be moved off the farm. He kept on about how he doesn’t hold with this war anyhow, and never did, how he went through the last one in the trenches and that was horror enough for one lifetime. “If people only knew what it was really like,” he said, and he sounded as if he was almost crying he was so angry. “If they knew, if they’d seen what I’ve seen, they’d never send young men off to fight again. Never.” He just wanted to be left alone in peace to do his farming.

Again and again Mum tried to reason with him, tried to tell him that everyone in the village was leaving, not just us; that no one wanted to go but we had to, so that the Americans could practise their landings, go over to France, and finish the war quickly. Then we’d all be back home soon enough and Dad would be back with us and the war would be over and done with. It would only be for a short time, she said. They’d promised. But Grandfather wouldn’t believe her and he wouldn’t believe them. He said the Yanks were just saying that so they could get him out.

In the end he slammed out of the house and left her. We heard Mum crying, so we went downstairs. Barry made her a cup of tea, and I held her hands and told her it would be all right, that I was sure Grandfather would give in and go in the end. But I was just saying it. He won’t go, not of his own accord anyway, not in a million years. They’ll have to carry him out, and, like Mum said, when they do it will break his heart.

Thursday, December 23rd 1943

Letter from Dad to all of us, wishing us a happy Christmas. He says he’s in Italy now, and it’s nothing but rain and mud and you go up one hill and there’s always another one ahead of you, but that at least each hill brings him nearer home. We’d just finished reading it at breakfast when there was a knock on the door. It was Mrs Blumfeld. She was bringing her Christmas card, she said. Mum asked her in. She was all red in the face and breathless from her cycling. It seemed so strange having her here in the house. She didn’t seem like our teacher at all, more like a visiting aunt. Tips was up on her lap as soon as she’d sat down. She sipped her tea and said how nice Tips was, even when she was sharpening her claws on her knees.

Then suddenly she looked across at Grandfather. I don’t remember everything she said, but it was something like this. “You and me, Mr Tregenza,” she said, “I think we have so much – how do you say it in English? – in common.” Grandfather looked a bit flummoxed (good word that). “They tell me you are the only one in the village who won’t leave. I would be just like you, I think. I loved our home in Holland, in Amsterdam. It is where I grew up. All I loved was in our home. But we had to leave; we could do nothing else. There was no choice for us because the Germans were coming. They were invading our country. We did what we could to stop them but it was no good. There were too many tanks and planes. They were too strong for us. My husband, Jacobus, was a Jew, Mr Tregenza. I am a Jew. We knew what they wanted to do with Jews. They wanted to kill us all, like rats, get rid of us. We knew this. So we had to leave our home. We came to England, Mr Tregenza, where we could be safe. Jacobus, he joined the merchant navy. He was a sea captain in Holland. We Dutch are good sailors, like you English. He was a good man and a very kind man, as you are – Barry has told me this and Lily too. They may have killed him, Mr Tregenza, but they have not killed me, not yet. They would if they could. If they come here they will.”

Grandfather’s eyes never left her face all the time she was talking. “That is why I ask you to leave your home, as I did, so that the American soldiers can come. They will borrow your house and your fields for a few months to do their practising. Then they can go across the sea and liberate my people and my country, and many other countries too. This way the Germans will never come here, never march in your streets. This way my people will not suffer any longer. I know it is hard, Mr Tregenza, but I ask you to do this for me, for my husband, for my country – for your country too. I think you will, because I know you have a good heart.”

I could see Grandfather’s eyes were full of tears. He got up, shrugged on his coat and pulled on his hat without ever saying a word. At the door he stopped and turned around. Then all he said was, “I’ll say one thing, missus. I wish I’d had a teacher like you when I was a little ‘un.” Then he went out and Barry ran out after him, and we were left there looking at one another in silence.

Mrs Blumfeld didn’t stay long after that, and we didn’t see Grandfather and Barry again until they came back for lunch. Grandfather was washing his hands in the sink when he suddenly said that he’d been thinking it over and that we could all start packing up after lunch, that he’d begin moving the sheep over to Uncle George’s right away, and he’d be needing both Barry and me to give him a hand. Then very quietly he said: “Just so long as we can come back afterwards.”

“We will, I promise,” Mum told him, and she went over to hug him. He cried then. That was the first time I’ve ever seen Grandfather cry.

Saturday, December 25th 1943

Christmas Day. There’s no point in pretending this was a happy Christmas. We tried to make the best of it. We had decorations everywhere as usual and a nice Christmas tree. We had our stockings all together in Grandfather’s bed. But Dad wasn’t there. Mum missed him a lot and so did I. Barry was homesick too and Grandfather was really down in the dumps all day and grumpy about moving. We had roast chicken for lunch, which did make everyone feel a little happier. I found a silver threepenny bit in the Christmas pudding and Barry found one too, so that made him forget he was homesick, for a while anyway. We all gave Grandfather a hand with the evening milking to cheer him up, and it worked, but not for long. There’s only a week to go now before we have to have everything out of here. It’s all Grandfather can think about. The house is piled high with tea chests and boxes. The curtains and lamp shades are all down, most of the crockery is already packed. We may have the Christmas decorations up, but it doesn’t feel at all like Christmas.

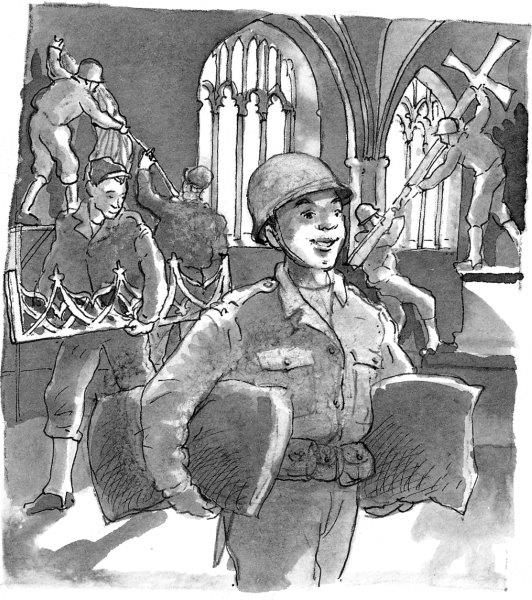

For my present I got a pair of red woolly gloves that Mum had knitted specially and secretly, and Barry had a navy blue scarf which he wears all the time, even at meal times. Mum didn’t knit that, she didn’t have time. We all went off to church this evening. It’s the last time we’ll be doing that for a long while. They’re going to empty it of all its precious things – stained glass windows, candlesticks, benches – in case they get damaged. The American soldiers are coming to take it all away. They’ll be putting sandbags around everything that’s too heavy to move, so that everything will be protected as much as possible. That’s what the vicar told us – he also said they’ll be needing all the help they can get. They’re starting to empty the church tomorrow. Mum says we’ve all got to be there to lend a hand.

I gave Tips some cold chicken this evening for her Christmas supper. She licked the plate until it was shiny clean. She’s a bit upset, I think. She knows something’s up. She can see it for herself and she can feel it too. I think she’s unhappy because she knows we’re unhappy.

I’m getting a bit fed up with Uncle George already, and we haven’t even moved in with him yet. All he talks about is the war: the Germans this and the Russians that. He sits there with his ear practically glued to the radio, tutting and huffing at the news. Even today, on Christmas Day, he has to go on and on about how we should “bomb Germany to smithereens, because of all they’ve done to us”! Then once he got talking about it, everyone was talking about it, arguing about it. So I came up to bed and left them to it. It’s supposed to be a day of peace and goodwill towards all men. And all they can talk about is the war. It makes me so sad, and I shouldn’t be sad on Christmas Day. But now I am. Happy Christmas, Dad.

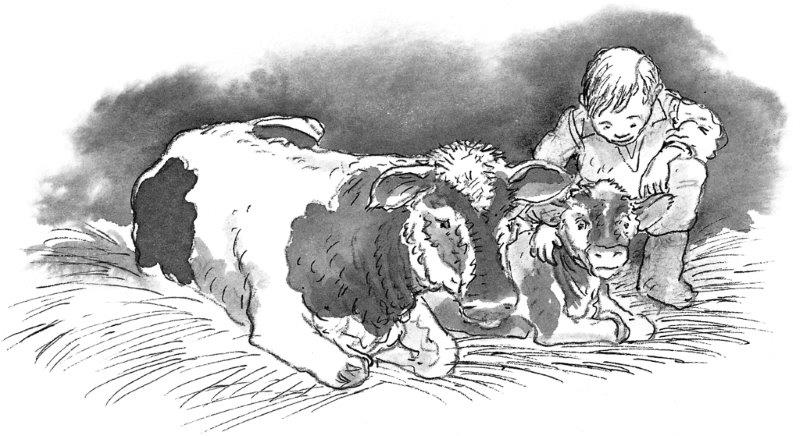

PS Just after I finished my diary I heard Barry crying in his room, so I went to see him. He didn’t want to tell me at first. Then he said he was just a bit homesick, missing his mum, he said. And his dad – mostly his dad. What could I say? My dad is alive and I’m living in my own home, going to my own school. Then I had an idea. “Shall we say Happy Christmas to the cows?” I said. He cheered up at once. So we crept downstairs in our dressing gowns and slippers, and ran out to the barn. They were all lying down in the straw grunting and chewing the cud, their calves curled up asleep beside them. Barry crouched down and stroked one of them, who sucked his finger until he giggled and pulled it out. We were walking back across the yard when he told me. “I hate the radio,” he said suddenly. “It’s always about the war, and the bombing raids, and that’s when I think of Mum most and miss her most. I don’t want her to die. I don’t want to be an orphan.”

I held his hand and squeezed it. I was too upset to say anything.

Sunday, December 26th 1943

I’ve had the strangest day and the happiest day for a long time. I met someone who’s the most different person I’ve ever met. He’s different in every way. He looks different, he sounds different, he is different. And, best of all, he’s my friend.

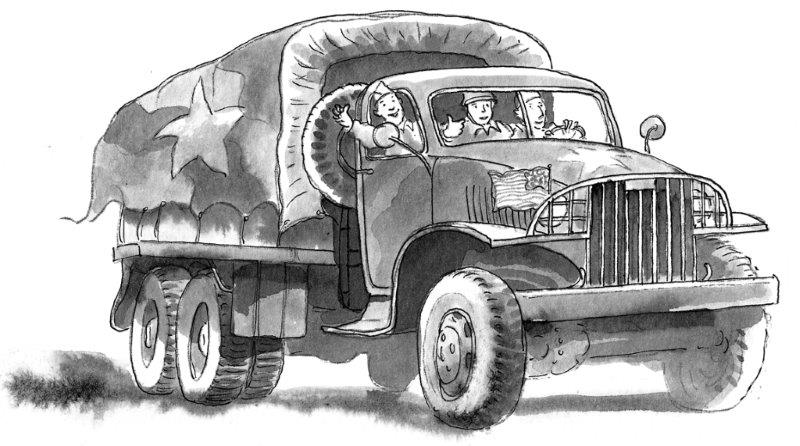

We were supposed to be helping to move things out of the church, but mostly we were just watching, because the Yanks were doing it all for us. Grandfather’s right: they do chew gum a lot. But they’re very happy-looking, always laughing and joking around. Some of them were carrying sandbags into the church, whilst others were carrying out the pews and chairs, hymn books and kneelers.

Suddenly I recognised one of them. He was the same black soldier I had seen in the jeep a while ago. And he recognised me too. “Hi there! How you doing?” he said. I never saw anyone smile like he did. His whole face lit up with it. He looked too young to be a soldier. He seemed so pleased to see me there, someone he recognised. He bent down so that his face was very close to mine. “I got three little sisters back home in Atlanta – that’s in Georgia and that’s in the United States of America, way across the sea,” he said. “And they’s all pretty, just like you.”

Then another soldier came along – I think he was a sergeant or something because he had lots of stripes on his arm, upside-down ones, not like our soldiers’ stripes at all. The sergeant told him he should be carrying sandbags, not chatting to kids. So he said, “Yessir.” Then he went off, smiling back at me over his shoulder. The next time I saw him he was coming past me with a sandbag under each arm. He stopped right by me and looked down at me from very high up. “What do you call yourself, girl?” he asked me. So I told him. Then he said, “I’m Adolphus T. Madison. (That’s T for Thomas.) Private First Class, US Army. My friends call me Adie. I’m mighty pleased to make your acquaintance, Lily. A ray of Atlanta sunshine, that’s what you are, a ray of Atlanta sunshine.”

No one has ever talked to me like that before. He looked me full in the eye as he spoke, so I knew he meant every word he said. But the sergeant shouted at him again and he had to go.

Then Barry came along, and for the rest of the morning we stood at the back of the church watching the soldiers coming and going, all of them fetching and carrying sandbags now, and Adie would give me a great big grin every time he went by. The vicar was fussing about them like an old hen, telling the Yank soldiers they had to be more careful, particularly when they were sandbagging the font. “That font’s very precious, you know,” said the vicar. I could see they didn’t like being pestered, but they were all too polite and respectful to say anything. The vicar kept on and on nagging at them. “It’s the most precious thing in the church. It’s Norman, you know, very old.” A couple of Yanks were just coming past us with more sandbags a few moments later when one of them said, “Who is this old Norman guy, anyway?”

After that Barry and me couldn’t stop ourselves giggling. The vicar told us we shouldn’t be giggling in church, so we went outside and giggled in the graveyard instead.

We told Grandfather and Mum about that when we got back this evening and they laughed so much they nearly cried. It’s been a happy, happy day. I hope Adie doesn’t get killed in the war. He’s so nice. I’m going to pray for him tonight, and for Dad too.