Полная версия:

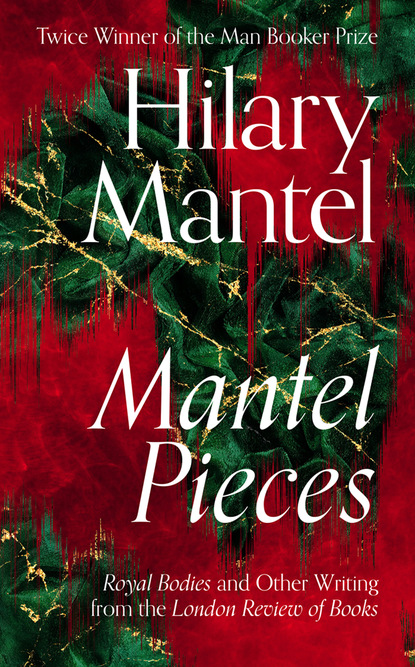

Mantel Pieces

MANTEL PIECES

Royal Bodies and Other Writing from the London Review of Books

Hilary Mantel

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020

Copyright © Tertius Enterprises Ltd 2020

All pieces previously published in the London Review of Books

Cover design by Julian Humphries

Cover images © Shutterstock

Hilary Mantel asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008429973

Ebook Edition © October 2020 ISBN: 9780008429980

Version: 2020-09-24

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction: Hilary Mantel

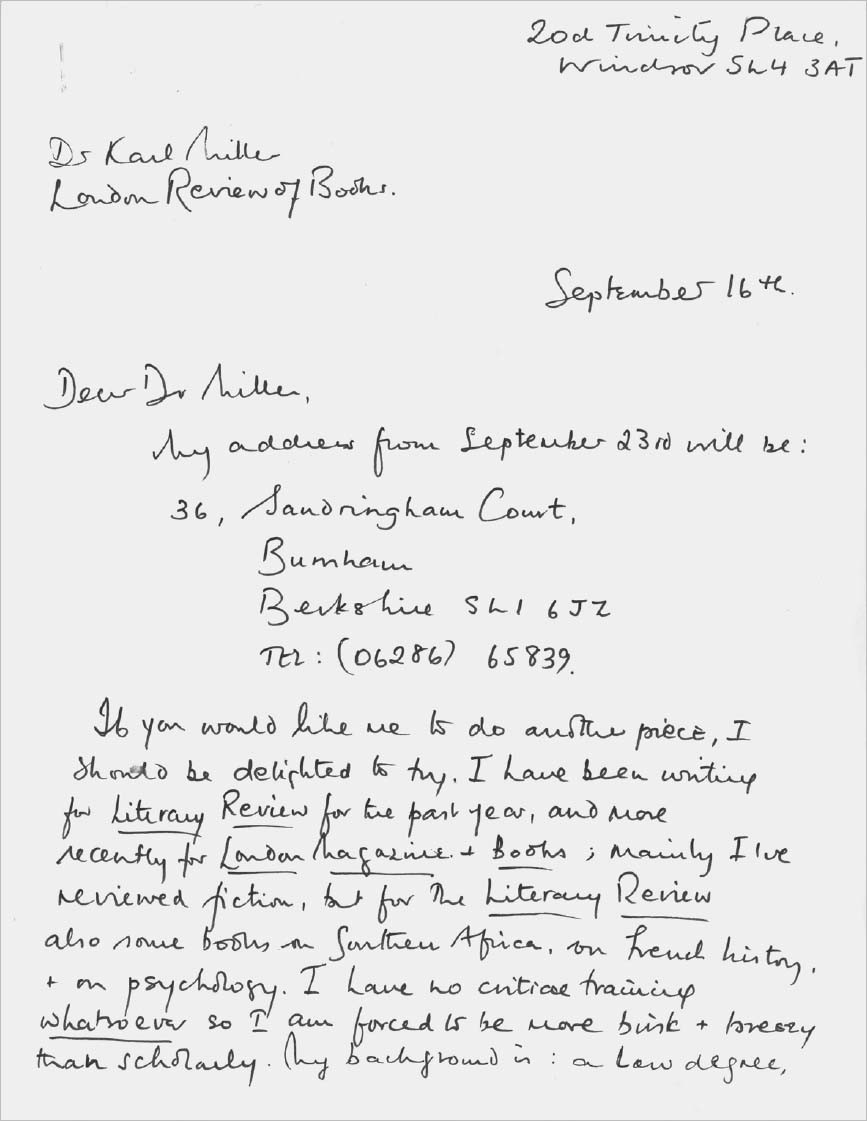

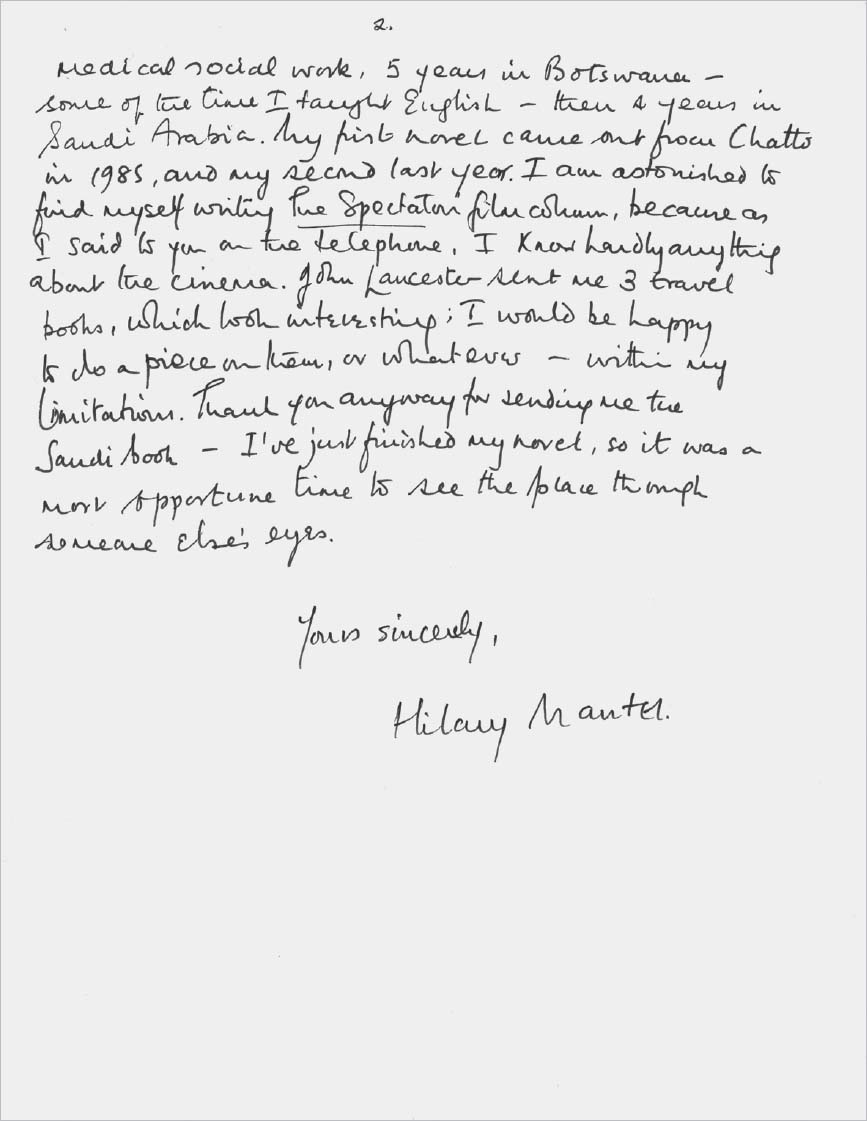

Letter from Hilary Mantel to Karl Miller, 1987

American Marriage, 1988

Letter from Mary-Kay Wilmers to Hilary Mantel, 1988

Bookcase Shopping in Jeddah, 1989

Postcard from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 1989

John Osborne’s Memoirs, 1991

Draft of a cover caption by Mary-Kay Wilmers, 1992

In Bed with Madonna, 1992

‘LRB’ cover, 28 May 1992

On Théroigne de Méricourt, 1992

Postcard from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 1997

On Christopher Marlowe, 1992

Fax from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 1994

A Mohawk Captive, 1994

Fax from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 1997

The Murder of James Bulger, 1997

Postcard and fax from Hilary Mantel, 1999

On Marie-Antoinette, 1999

Email from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 2001

Britain’s Last Witch, 2001

Email from Hilary Mantel to the editors, 2003

Meeting My Stepfather, 2003

Card and email from Hilary Mantel to the editors, 2003

The Hair Shirt Sisterhood, 2004

‘LRB’ covers, 24 March 2004 and 20 April 2006

The People’s Robespierre, 2006

Email from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 2005

On Jane Boleyn, 2008

Email from Hilary Mantel to the editors, 2006

‘LRB’ cover, 9 April 2009

Marian Devotion, 2009

On Danton, 2009

‘LRB’ cover, 4 November 2010

Meeting the Devil, 2010

Email from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 2012

Royal Bodies, 2013

Emails from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 2013

On Charles Brandon, 2016

Fact-checking correspondence, 2016

The Secrets of Margaret Pole, 2017

Email from Hilary Mantel to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 2019

Footnotes

About the LRB

About 4th Estate

About the Author

Also by Hilary Mantel

About the Publisher

Introduction

Hilary Mantel

WHEN my first novel, Every Day Is Mother’s Day, was published in 1985, I had been living abroad for some years. Its sequel came out a year later, and at that point, returning from Saudi Arabia, I needed to work out whether I could make a living as a writer. The advance for my first book had been £2000. For my second it was £4000 – a good rate of progress, but not an income. Apart from my agent and publishers, I didn’t know anyone in the media, or a single other person who was a writer. But I didn’t think I was equipped for any other trade.

The first person to throw me a lifeline was Auberon Waugh, who had reviewed my novels and who asked me to write for the Literary Review: one piece a month, £40. Alan Ross at the London Magazine employed me; he was able to pay even less. But I decided I would say ‘yes’ to anything, especially if it frightened me. Soon Charles Moore at the Spectator became my patron, and offered me their film column. A weekly column made me visible, and led to more work than I could handle.

The reviewing scene was very different in those days. There were more daily papers and they made space for books. For a time, in the autumn of 1989 and the spring of 1990, there were five Sunday broadsheets, all of them eating up copy. There were periodicals that no longer exist, like New Society and the Listener. There was even one called Books and Bookmen – the title tells you everything about the world in which I started to publish.

Writing in 1938, Cyril Connolly identified journalism as one of his Enemies of Promise. He warns young writers against reviewing, identifying the danger of ‘short articles for quick returns’ – though in his day, two thousand words was considered short. He insists that ‘any other way of making money would be better … reviewing is a whole-time job with a halftime salary.’ The author runs the risk of losing energy, ‘frittering it away on tripe and discovering that it is his flashiest efforts that receive most praise’. The only way to preserve yourself, Connolly advises, is to ‘manoeuvre’ so you never review a bad book.

It is true that reviewing eats up time. Even in the easier days in which I began, you had to become a workhorse if you wanted worthwhile returns. I was in awe of my paymasters, and at the same time I was uneasy. I recall having a batch of potential Booker winners fall out of a bag – four or five of them, and a scant two hundred words for each. I was offering opinions with no visible means of support, and with little scope for nuance. It is simple, if you have only a paragraph to spare, to swat a book like a fly. Even if you have more space, it is easier to write a bad review than a good one, or to locate the flaw in a book and become fixated on it. Young reviewers become fired with zeal against the established and the over-rated. They think they are doing justice, but it takes them longer to learn about mercy.

When I began to write for the LRB everything changed. I began my career during Karl Miller’s editorship and continued with Mary-Kay Wilmers. My pieces became more expansive, the work became more challenging, and my unease dissipated, though only gradually. I still said ‘yes’ to everything. Mary-Kay speaks so softly that when she first called me I believed she was trapped inside a sofa. It’s possible that I didn’t always know what I had agreed to review. But I learned that the paper is skilled at matching contributors to a task. I almost never got a bad book – and if I did, I could send it back. At first I had qualms about my ability to rise to the standard. What I wrote was so plain that it felt exposed. I didn’t have an arts degree, had never learned about literary criticism; in the theory wars, I was a non-combatant. But the paper had experts on tap, if they cared to call on them. If they wanted someone to stand in for the general reader, I was as general as they come. I didn’t often review fiction, so I was not in danger of projecting my own perplexities onto someone else’s work. And I welcomed the fact that all editorial changes were by negotiation. There was no danger of a sub-editor slicing off your last paragraph and changing the whole meaning of the piece. There were no particular space constraints. When I asked ‘How many words?’ the editors would say, ‘Take what you need.’

That answer is a clever one, and more demanding than it appears. To fix a book in context needs background reading. When the paper unearthed my old letters – I had no idea they kept such things – I saw that I was always asking for time, more time to learn – and it was always granted. Sometimes I was slow because I was over-committed, but sometimes because I was fascinated. The editors forgave my occasional bouts of critic’s block. They are forbearing with all their writers; sometimes it must seem unclear whether a piece is in progress or regress, or whether it will ever arrive at all. I am indebted to them for patience, and to Mary-Kay for encouraging me out of my shell. I had trained myself out of digression, but the paper was at ease with it. I was wary of jokes, but they didn’t mind those either. And when I wanted to say something more personal, they were listening.

The pieces here were written over a long period, and fall into different categories. There are those where, as I have said, I stand in for the general reader. There are pieces on the early Tudors and on the French Revolution, where I have particular knowledge. There are diary pieces, offcuts of memoir. And then there is a category of one: my piece on royal bodies, which supposedly enraged middle England – or at least, left certain newspapers spitting and foaming and doubling up in ire.

‘Royal Bodies’ began life as an LRB lecture. Afterwards it was printed, and nothing happened for a while – and I didn’t expect anything to result from a sober and harmless essay, although I did wonder if Buckingham Palace might be irked because I mocked their cocktail snacks. Ten days on, the press were on my doorstep – or somewhere near it. From my window overlooking the sea, I watched hopeless reporters range up and down, trying to work out how to catch me. They could not decide exactly where I lived, and the neighbours wouldn’t help them – in Budleigh Salterton we don’t engage with vulgarians. My husband came to tell me that the prime minister and the leader of the opposition were denouncing me. Neither, I believe, had read my lecture. Very few people had read it, but I was still Monster of the Month. If it had been bonfire season no doubt I would have been burned in effigy.

The ashes are frequently raked over, and I have to live with a traitor’s name. But the prime minister of those days, and the leader of the opposition too, are shrinking into obscurity, while the LRB expands its readership and reach year by year, never shy of disputes and never trapped into faux-apologetic mode. I am proud to work for a paper so unafraid, so original and so current. The more books I turn out, the more I wonder how one ever finds the courage to begin, and the more I respect other people who write. So many volumes, so much toil, so much hope: the least we owe our writers is dispassionate assessment and considered response.

The LRB offers more than that. A literary journal must be a political journal, as we cannot detach from larger realities. The paper is at ease with controversy rather than consensus and will allow a contributor to be contrary, even unfashionable. I have felt no pressure to line up with the editors’ views – just as I felt no need to become a Tory to write for the Spectator. Most imaginative writers are a party of one, and it is a riven and dissenting party, waging wars privately, silently. We do not like to be forced into confining self-definitions, or into consistency of response, or easy declarations of intent: or at least, we should not like it. Sometimes when I have written a piece for the LRB, I feel I understand less than when I started. What I knew, I have begun to unknow. I have not in fact finished, but begun a new engagement with a topic, an exploration that might stretch over years. There is, therefore, a temptation to write afterthoughts into these pieces, to embellish them with later and better thinking. I have not done that, but left them as they were – mantelpieces littered with to-do lists, and messages from people I used to be.

Letter from Hilary Mantel to Karl Miller, 1987

Women in Pain

American Marriage

1988

SCRIBBLE, scribble, scribble, Ms Hite: another damned, thick, square book.[1] Shere Hite is a ‘cultural historian’. She has already given us The Hite Report: A Nationwide Study of Female Sexuality and The Hite Report on Male Sexuality. Her work is an uneasy blend of prurience and pedantry; an attenuated blonde woman with curious white make-up, she has offended US feminists by making money out of sisterhood. She lives in some style, and has a young husband who, she tells us in a preface (there are many prefaces, a sort of philosophical foreplay), ‘fills my life with poetry and music, more every day’. Well, that’s all right then.

But sadly, it’s not typical. What a picture of American marriage emerges from these pages! It is certainly a ‘sad, sour, sober beverage’. (There is so much in these pages that Lord Byron said first, and better, and with merciful brevity, and without the advantages of sociological research.) The men are always off on a fishing trip, the women always masturbating in the bathroom. When he comes home, they fight; she rants, and he sits there ‘like Mussolini’. Then maybe he smashes a little crockery. They have sex by way of reconciliation, but it’s not too good: ‘I have to remind him to remove his glasses.’

This is a book about emotional suffering. There is the odd woman who says she is happy. There is even a section called ‘The Beauty of Marriage’. It occupies page 343 – but then a lot of page 343 is white space. Most of these nine hundred pages tell of disaffection, disillusion and incipient rebellion. ‘Should Women,’ asks one heading, ‘Take a Mass Vacation From Trying To Understand Men?’ Miss Hite’s respondent tells us: ‘Men’s attitudes are so bad, so impaired, and they don’t even realise how negative to women they are. They think they love women. It will take some massive reaction to make them start realising, start thinking … like a national strike, a boycott, a new Lysistrata.’ Or as Shere Hite herself puts it, less dramatically: ‘Women are suffering a lot of pain in their love relationships with men.’

Half the world’s fiction is about this, but Hite wants to skewer it into a scientific fact. She is particular, though, about the definitions of science that she will admit. One thinks of the aperçu of the younger Amis: ‘I don’t know much about science, but I know what I like.’ The basis of her inquiry was a questionnaire which runs to 127 pages. She eschews multiple-choice questions (quite properly, because they put a damper on things) and goes for the ‘open-ended’, which allows her respondents to answer in essay form if they wish. She distributed 100,000 questionnaires, and got 4,500 replies – not bad going, whatever her opponents say. Miss Hite’s methodology has been attacked rather unfairly, and so often that she has buttressed her report with experts – professors all – who assure us of her probity and competence as a social scientist. Her opponents have picked up the term ‘random sample’ – a staple of saloon-bar wisdom – and have said she hasn’t got one. What matters, she says reasonably, is to have a sample that is demographically matched to the population.

What is less reasonable, and more an act of faith, is Hite’s contention that because her respondents were anonymous they must have been telling the truth. In the context of the study, the most one can hope is that they were telling the truth as interpreted by their feelings on the day that they answered. It is a characteristic of sociologists that they discount the grimly insistent nature of the human imagination. There is a chilling quality about Miss Hite’s respondents which reminds one of all those people who say: ‘I’ve got a book in me.’ Of course, everyone has: what is a pity is that exercises like The New Hite Report give it the opportunity to come out.

The buttressing professors pose problems of their own. ‘Hite,’ says one, ‘has rejected the silencing of women by recognising that a theory about women’s ways of loving must be rooted in our own experiences.’ You must do what you can with that sentence. You can read it backwards. You can try to put it out of your mind for a few days, and leave it in a room by itself, then spring back in and hope to take its meaning unawares. Probably it means that a good way to find out what people think is just to ask them. But then, you may object, their replies will be merely subjective – no use really, if you purport to be a scientist. Take back that ‘merely’. Wash your mouth out. Feminist science is something quite different; subjectivity is of the essence. Until recently, women have been objects of study, and all the theories about feminine psychology, about how women think and feel, have been constructed by men. They have been constructed, very often, in the expectation of finding pathology, or at least a rather humiliating state of things: she is smitten by penis envy, by frigidity, if she can’t have an orgasm from the Saturday Night Special she’s some deeply unnatural woman. She’s neurotic, and obsessed with one little bit of her anatomy that some civilisations delight in slicing off.

There is nothing controversial here. For controversy one must look a little further. Miss Hite belongs to the school of thought which rejects traditional, male-devised science; she says it is crampingly linear in its mode of thought, and mistakenly claims to be value-free, detached and neutral. Feminist science recognises its evaluative posture; it recognises that the observer is not neutral, for she has her position, her prejudices, her viewpoint; it values intuition. Hite takes comfort from vogues in literary criticism – text, not machine, as analyst’s model – and from Heidegger: ‘reason, glorified for centuries, is the most stiff-necked adversary of thought.’ An essay appended to the book says that white male thinkers (it is a puzzle to know how skin colour gets in) are uncomfortable with hermeneutics: ‘for them it raises the spectre of total relativity, the fear that we will never be able to know anything in an absolutely objective and certain way.’ It is possible, of course, that many scientists – physicists especially, and white and male at that – have been living with this ‘fear’ for many years; that it is now a necessary part of whatever understanding of the universe we have. But they have not entirely been frightened out of the scientific method; it has its uses, and when Shere Hite wishes to be sure that she will be taken seriously, she displays an old-fashioned masculine zeal for quantification. The questionnaire asks: ‘How happy are you, on a scale of 1-10?’ It’s a question which – if we accept Shere Hite’s views up to this point – incorporates the worst of both ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ science; its only merit is that it makes us laugh.

The truth may be that The Hite Report is science, but not of the mould-breaking sort its author thinks it is; that in fact it’s just the usual kind, which offers incomprehensible explanations for what everyone knows. Sociology has never made it into the gentlemen’s club of the ‘hard’ sciences; many people have suspected that it is simply a higher form of gossip.

Considered as gossip, though, this book has a grave defect: all Miss Hite’s anonymous respondents sound alike. She insists that women of all classes were well represented, that the less educated were not deterred from writing essays on their lives; in some cases, she says, the misspellings were ‘very appealing’. But they did not find their way into the finished product, because, Miss Hite says, ‘it seemed that in print these misspellings sometimes looked demeaning to the writer, or might be seen as trivialising that respondent.’ Then, too, some of these women adore jargon: as if all their lives have been a preparation for a survey; perhaps it is because they have ‘therapists’ to contend with, as well as their families. Their range is small, their vocabulary often restricted, and there is a huge gulf between their emotion and their capacity to convey it: being a lesbian, says one, ‘is the most comforting identity I’ve had since I was a cheerleader in junior high school’. The book’s tone is homogeneous, dull, flat: all these thousands of women sound like one woman, one awful person, droning on and on. If only Miss Hite were not so contemptuous of pop sociologists, she could have given her informants fictitious names, and to each one accorded a little pen-picture, to encourage us into her narrative: ‘Mary Lou, a much tattooed redhead of 43 …’

Yet the book does have its fascination. Between the lines are the sagas, the epics, the unwritten histories, a novel condensed into a throwaway phrase. It is not that what the women have to say is very original: it is that their reports, by their weight, their mass, offer such resounding confirmation of the absurdity of life. The relationships Shere Hite surveys are so painful, and so achingly comic, that one wonders how anyone came up with the notion in the first place that men and women might live together: whoever thought it might be possible?

Language is the first problem. There are men who seemed biologically programmed to avoid it. ‘My clue that something is bothering him is when he grinds his teeth when he sleeps.’ If they do talk, it might be about the weather: one woman says acidly that after 31 years she finds the weather is no longer interesting. They say, these men: ‘What is the baseball score? Put on the basketball game!’ Women like talking – about everything. According to men, they always choose ‘soapopera topics’. While they are indulging in these, the men ‘whistle and sing and slam doors’. Sometimes they absentmindedly walk off into other rooms. If they answer, it may be completely at random. ‘I will ask,’ says one misunderstood soul, ‘two or three questions at once – example: “Do you want milk or coffee?” And he will answer: “Yes.” He feels,’ the woman explains, ‘that I should ask them one at a time.’ Another describes her marital small talk as ‘like pulling teeth’.

Ninety-eight per cent of these women say they want more ‘verbal closeness’ with men; and they want to offer emotional support when they see that life is getting to their partners. When their offer is rejected, they feel baffled and useless. (One man lost his job, his father, and the wheels off his car. His wife expressed sympathy, so he slapped her.) The men repress their feelings, and deny that women have any; one of the gay women, who has opted out of the whole thing, says that she can’t imagine falling in love with a man, because men are so alien, ‘as if they all come from the East Coast and women from the West’. For the women who decide to stay in heterosexual relationships, there is one ultimate uncertainty: ‘I wonder if he has any emotions at all?’