Полная версия:

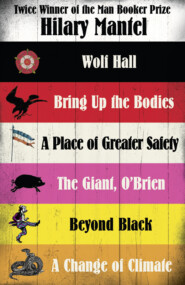

Hilary Mantel Collection: Six of Her Best Novels

‘I'll pay you back,’ he says. ‘I might go and be a soldier. I could send you a fraction of my pay and I might get loot.’

Morgan says, ‘But there isn't a war.’

‘There'll be one somewhere,’ Kat says.

‘Or I could be a ship's boy. But, you know, Bella – do you think I should go back for her? She was screaming. He had her shut up.’

‘So she wouldn't nip his toes?’ Morgan says. He's satirical about Bella.

‘I'd like her to come away with me.’

‘I've heard of a ship's cat. Not of a ship's dog.’

‘She's very small.’

‘She'll not pass for a cat,’ Morgan laughs. ‘Anyway, you're too big all round for a ship's boy. They have to run up the rigging like little monkeys – have you ever seen a monkey, Tom? Soldier is more like it. Be honest, like father like son – you weren't last in line when God gave out fists.’

‘Right,’ Kat said. ‘Shall we see if we understand this? One day my brother Tom goes out fighting. As punishment, his father creeps up behind and hits him with a whatever, but heavy, and probably sharp, and then, when he falls down, almost takes out his eye, exerts himself to kick in his ribs, beats him with a plank of wood that stands ready to hand, knocks in his face so that if I were not his own sister I'd barely recognise him: and my husband says, the answer to this, Thomas, is go for a soldier, go and find somebody you don't know, take out his eye and kick in his ribs, actually kill him, I suppose, and get paid for it.’

‘May as well,’ Morgan says, ‘as go fighting by the river, without profit to anybody. Look at him – if it were up to me, I'd have a war just to employ him.’

Morgan takes out his purse. He puts down coins: chink, chink, chink, with enticing slowness.

He touches his cheekbone. It is bruised, intact: but so cold.

‘Listen,’ Kat says, ‘we grew up here, there's probably people that would help Tom out –’

Morgan gives her a look: which says, eloquently, do you mean there are a lot of people would like to be on the wrong side of Walter Cromwell? Have him breaking their doors down? And she says, as if hearing his thought out loud, ‘No. Maybe. Maybe, Tom, it would be for the best, do you think?’

He stands up. She says, ‘Morgan, look at him, he shouldn't go tonight.’

‘I should. An hour from now he'll have had a skinful and he'll be back. He'd set the place on fire if he thought I were in it.’

Morgan says, ‘Have you got what you need for the road?’

He wants to turn to Kat and say, no.

But she's turned her face away and she's crying. She's not crying for him, because nobody, he thinks, will ever cry for him, God didn't cut him out that way. She's crying for her idea of what life should be like: Sunday after church, all the sisters, sisters-in-law, wives kissing and patting, swatting at each other's children and at the same time loving them and rubbing their little round heads, women comparing and swapping babies, and all the men gathering and talking business, wool, yarn, lengths, shipping, bloody Flemings, fishing rights, brewing, annual turnover, nice timely information, favour-for-favour, little sweeteners, little retainers, my attorney says … That's what it should be like, married to Morgan Williams, with the Williamses being a big family in Putney … But somehow it's not been like that. Walter has spoiled it all.

Carefully, stiffly, he straightens up. Every part of him hurts now. Not as badly as it will hurt tomorrow; on the third day the bruises come out and you have to start answering people's questions about why you've got them. By then he will be far from here, and presumably no one will hold him to account, because no one will know him or care. They'll think it's usual for him to have his face beaten in.

He picks up the money. He says, ‘Hwyl, Morgan Williams. Diolch am yr arian.’ Thank you for the money. ‘Gofalwch am Katheryn. Gofalwch am eich busness. Wela I chi eto rhywbryd. Pobl lwc.’

Look after my sister. Look after your business. See you again sometime.

Morgan Williams stares.

He almost grins; would do, if it wouldn't split his face open. All those days he'd spent hanging around the Williamses' households: did they think he'd just come for his dinner?

‘Pobl lwc,’ Morgan says slowly. Good luck.

He says, ‘If I follow the river, is that as good as anything?’

‘Where are you trying to get?’

‘To the sea.’

For a moment, Morgan Williams looks sorry it has come to this. He says, ‘You'll be all right, Tom? I tell you, if Bella comes looking for you, I won't send her home hungry. Kat will give her a pie.’

He has to make the money last. He could work his way downriver; but he is afraid that if he is seen, Walter will catch him, through his contacts and his friends, those kind of men who will do anything for a drink. What he thinks of, first, is slipping on to one of the smugglers' ships that go out of Barking, Tilbury. But then he thinks, France is where they have wars. A few people he talks to – he talks to strangers very easily – are of the same belief. Dover then. He gets on the road.

If you help load a cart you get a ride in it, as often as not. It gives him to think, how bad people are at loading carts. Men trying to walk straight ahead through a narrow gateway with a wide wooden chest. A simple rotation of the object solves a great many problems. And then horses, he's always been around horses, frightened horses too, because when in the morning Walter wasn't sleeping off the effects of the strong brew he kept for himself and his friends, he would turn to his second trade, farrier and blacksmith; and whether it was his sour breath, or his loud voice, or his general way of going on, even horses that were good to shoe would start to shake their heads and back away from the heat. Their hooves gripped in Walter's hands, they'd tremble; it was his job to hold their heads and talk to them, rubbing the velvet space between their ears, telling them how their mothers love them and talk about them still, and how Walter will soon be over.

He doesn't eat for a day or so; it hurts too much. But by the time he reaches Dover the big gash on his scalp has closed, and the tender parts inside, he trusts, have mended themselves: kidneys, lungs and heart.

He knows by the way people look at him that his face is still bruised. Morgan Williams had done an inventory of him before he left: teeth (miraculously) still in his head, and two eyes, miraculously seeing. Two arms, two legs: what more do you want?

He walks around the docks saying to people, do you know where there's a war just now?

Each man he asks stares at his face, steps back and says, ‘You tell me!’

They are so pleased with this, they laugh at their own wit so much, that he continues asking, just to give people pleasure.

Surprisingly, he finds he will leave Dover richer than he arrived. He'd watched a man doing the three-card trick, and when he learned it he set up for himself. Because he's a boy, people stop to have a go. It's their loss.

He adds up what he's got and what he's spent. Deduct a small sum for a brief grapple with a lady of the night. Not the sort of thing you could do in Putney, Wimbledon or Mortlake. Not without the Williams family getting to know, and talking about you in Welsh.

He sees three elderly Lowlanders struggling with their bundles and moves to help them. The packages are soft and bulky, samples of woollen cloth. A port officer gives them trouble about their documents, shouting into their faces. He lounges behind the clerk, pretending to be a Lowland oaf, and tells the merchants by holding up his fingers what he thinks a fair bribe. ‘Please,’ says one of them, in effortful English to the clerk, ‘will you take care of these English coins for me? I find them surplus.’ Suddenly the clerk is all smiles. The Lowlanders are all smiles; they would have paid much more. When they board they say, ‘The boy is with us.’

As they wait to cast off, they ask him his age. He says eighteen, but they laugh and say, child, you are never. He offers them fifteen, and they confer and decide that fifteen will do; they think he's younger, but they don't want to shame him. They ask what's happened to his face. There are several things he could say but he selects the truth. He doesn't want them to think he's some failed robber. They discuss it among themselves, and the one who can translate turns to him: ‘We are saying, the English are cruel to their children. And cold-hearted. The child must stand if his father comes in the room. Always the child should say very correctly, “my father, sir”, and “madam my mother”.’

He is surprised. Are there people in the world who are not cruel to their children? For the first time, the weight in his chest shifts a little; he thinks, there could be other places, better. He talks; he tells them about Bella, and they look sorry, and they don't say anything stupid like, you can get another dog. He tells them about the Pegasus, and about his father's brewhouse and how Walter gets fined for bad beer at least twice a year. He tells them about how he gets fines for stealing wood, cutting down other people's trees, and about the too-many sheep he runs on the common. They are interested in that; they show the woollen samples and discuss among themselves the weight and the weave, turning to him from time to time to include and instruct him. They don't think much of English finished cloth generally, though these samples can make them change their mind … He loses the thread of the conversation when they try to tell him their reasons for going to Calais, and different people they know there.

He tells them about his father's blacksmith business, and the English-speaker says, interested, can you make a horseshoe? He mimes to them what it's like, hot metal and a bad-tempered father in a small space. They laugh; they like to see him telling a story. Good talker, one of them says. Before they dock, the most silent of them will stand up and make an oddly formal speech, at which one will nod, and which the other will translate. ‘We are three brothers. This is our street. If ever you visit our town, there is a bed and hearth and food for you.’

Goodbye, he will say to them. Goodbye and good luck with your lives. Hwyl, cloth men. Golfalwch eich busness. He is not stopping till he gets to a war.

The weather is cold but the sea is flat. Kat has given him a holy medal to wear. He has slung it around his neck with a cord. It makes a chill against the skin of his throat. He unloops it. He touches it with his lips, for luck. He drops it; it whispers into the water. He will remember his first sight of the open sea: a grey wrinkled vastness, like the residue of a dream.

II Paternity 1527

So: Stephen Gardiner. Going out, as he's coming in. It's wet, and for a night in April, unseasonably warm, but Gardiner wears furs, which look like oily and dense black feathers; he stands now, ruffling them, gathering his clothes about his tall straight person like black angel's wings.

‘Late,’ Master Stephen says unpleasantly.

He is bland. ‘Me, or your good self?’

‘You.’ He waits.

‘Drunks on the river. The boatmen say it's the eve of one of their patron saints.’

‘Did you offer a prayer to her?’

‘I'll pray to anyone, Stephen, till I'm on dry land.’

‘I'm surprised you didn't take an oar yourself. You must have done some river work, when you were a boy.’

Stephen sings always on one note. Your reprobate father. Your low birth. Stephen is supposedly some sort of semi-royal by-blow: brought up for payment, discreetly, as their own, by discreet people in a small town. They are wool-trade people, whom Master Stephen resents and wishes to forget; and since he himself knows everybody in the wool trade, he knows too much about his past for Stephen's comfort. The poor orphan boy!

Master Stephen resents everything about his own situation. He resents that he's the king's unacknowledged cousin. He resents that he was put into the church, though the church has done well by him. He resents the fact that someone else has late-night talks with the cardinal, to whom he is confidential secretary. He resents the fact that he's one of those tall men who are hollow-chested, not much weight behind him; he resents his knowledge that if they met on a dark night, Master Thos. Cromwell would be the one who walked away dusting off his hands and smiling.

‘God bless you,’ Gardiner says, passing into the night unseasonably warm.

Cromwell says, ‘Thanks.’

The cardinal, writing, says without looking up, ‘Thomas. Still raining? I expected you earlier.’

Boatman. River. Saint. He's been travelling since early morning and in the saddle for the best part of two weeks on the cardinal's business, and has now come down by stages – and not easy stages – from Yorkshire. He's been to his clerks at Gray's Inn and borrowed a change of linen. He's been east to the city, to hear what ships have come in and to check the whereabouts of an off-the-books consignment he is expecting. But he hasn't eaten, and hasn't been home yet.

The cardinal rises. He opens a door, speaks to his hovering servants. ‘Cherries! What, no cherries? April, you say? Only April? We shall have sore work to placate my guest, then.’ He sighs. ‘Bring what you have. But it will never do, you know. Why am I so ill-served?’

Then the whole room is in motion: food, wine, fire built up. A man takes his wet outer garments with a solicitous murmur. All the cardinal's household servants are like this: comfortable, soft-footed, and kept permanently apologetic and teased. And all the cardinal's visitors are treated in the same way. If you had interrupted him every night for ten years, and sat sulking and scowling at him on each occasion, you would still be his honoured guest.

The servants efface themselves, melting away towards the door. ‘What else would you like?’ the cardinal says.

‘The sun to come out?’

‘So late? You tax my powers.’

‘Dawn would do.’

The cardinal inclines his head to the servants. ‘I shall see to this request myself,’ he says gravely; and gravely they murmur, and withdraw.

The cardinal joins his hands. He makes a great, deep, smiling sigh, like a leopard settling in a warm spot. He regards his man of business; his man of business regards him. The cardinal, at fifty-five, is still as handsome as he was in his prime. Tonight he is dressed not in his everyday scarlet, but in blackish purple and fine white lace: like a humble bishop. His height impresses; his belly, which should in justice belong to a more sedentary man, is merely another princely aspect of his being, and on it, confidingly, he often rests a large, white, beringed hand. A large head – surely designed by God to support the papal tiara – is carried superbly on broad shoulders: shoulders upon which rest (though not at this moment) the great chain of Lord Chancellor of England. The head inclines; the cardinal says, in those honeyed tones, famous from here to Vienna, ‘So now, tell me how was Yorkshire.’

‘Filthy.’ He sits down. ‘Weather. People. Manners. Morals.’

‘Well, I suppose this is the place to complain. Though I am already speaking to God about the weather.’

‘Oh, and the food. Five miles inland, and no fresh fish.’

‘And scant hope of a lemon, I suppose. What do they eat?’

‘Londoners, when they can get them. You have never seen such heathens. They're so high, low foreheads. Live in caves, yet they pass for gentry in those parts.’ He ought to go and look for himself, the cardinal; he is Archbishop of York, but has never visited his see. ‘And as for Your Grace's business –’

‘I am listening,’ the cardinal says. ‘Indeed, I go further. I am captivated.’

As he listens, the cardinal's face creases into its affable, perpetually attentive folds. From time to time he notes down a figure that he is given. He sips from a glass of his very good wine and at length he says, ‘Thomas … what have you done, monstrous servant? An abbess is with child? Two, three abbesses? Or, let me see … Have you set fire to Whitby, on a whim?’

In the case of his man Cromwell, the cardinal has two jokes, which sometimes unite to form one. The first is that he walks in demanding cherries in April and lettuce in December. The other is that he goes about the countryside committing outrages, and charging them to the cardinal's accounts. And the cardinal has other jokes, from time to time: as he requires them.

It is about ten o'clock. The flames of the wax candles bow civilly to the cardinal, and stand straight again. The rain – it has been raining since last September – splashes against the glass window. ‘In Yorkshire,’ he says, ‘your project is disliked.’

The cardinal's project: having obtained the Pope's permission, he means to amalgamate some thirty small, ill-run monastic foundations with larger ones, and to divert the income of these foundations – decayed, but often very ancient – into revenue for the two colleges he is founding: Cardinal College, at Oxford, and a college in his home town of Ipswich, where he is well remembered as the scholar son of a prosperous and pious master butcher, a guild-man, a man who also kept a large and well-regulated inn, of the type used by the best travellers. The difficulty is … No, in fact, there are several difficulties. The cardinal, a Bachelor of Arts at fifteen, a Bachelor of Theology by his mid-twenties, is learned in the law but does not like its delays; he cannot quite accept that real property cannot be changed into money, with the same speed and ease with which he changes a wafer into the body of Christ. When he once, as a test, explained to the cardinal just a minor point of the land law concerning – well, never mind, it was a minor point – he saw the cardinal break into a sweat and say, Thomas, what can I give you, to persuade you never to mention this to me again? Find a way, just do it, he would say when obstacles were raised; and when he heard of some small person obstructing his grand design, he would say, Thomas, give them some money to make them go away.

He has the leisure to think about this, because the cardinal is staring down at his desk, at the letter he has half-written. He looks up. ‘Tom …’ And then, ‘No, never mind. Tell me why you are scowling in that way.’

‘The people up there say they are going to kill me.’

‘Really?’ the cardinal says. His face says, I am astonished and disappointed. ‘And will they kill you? Or what do you think?’

Behind the cardinal is a tapestry, hanging the length of the wall. King Solomon, his hands stretched into darkness, is greeting the Queen of Sheba.

‘I think, if you're going to kill a man, do it. Don't write him a letter about it. Don't bluster and threaten and put him on his guard.’

‘If you ever plan to be off your guard, let me know. It is something I should like to see. Do you know who … But I suppose they don't sign their letters. I shall not give up my project. I have personally and carefully selected these institutions, and His Holiness has approved them under seal. Those who object misunderstand my intention. No one is proposing to put old monks out on the roads.’

This is true. There can be relocation; there can be pensions, compensation. It can be negotiated, with goodwill on both sides. Bow to the inevitable, he urges. Deference to the lord cardinal. Regard his watchful and fatherly care; believe his keen eye is fixed on the ultimate good of the church. These are the phrases with which to negotiate. Poverty, chastity and obedience: these are what you stress when you tell some senile prior what to do. ‘They don't misunderstand,’ he says. ‘They just want the proceeds themselves.’

‘You will have to take an armed guard when next you go north.’

The cardinal, who thinks upon a Christian's last end, has had his tomb designed already, by a sculptor from Florence. His corpse will lie beneath the outspread wings of angels, in a sarcophagus of porphyry. The veined stone will be his monument, when his own veins are drained by the embalmer; when his limbs are set like marble, an inscription of his virtues will be picked out in gold. But the colleges are to be his breathing monument, working and living long after he is gone: poor boys, poor scholars, carrying into the world the cardinal's wit, his sense of wonder and of beauty, his instinct for decorum and pleasure, his finesse. No wonder he shakes his head. You don't generally have to give an armed guard to a lawyer. The cardinal hates any show of force. He thinks it unsubtle. Sometimes one of his people – Stephen Gardiner, let's say – will come to him denouncing some nest of heretics in the city. He will say earnestly, poor benighted souls. You pray for them, Stephen, and I'll pray for them, and we'll see if between us we can't bring them to a better state of mind. And tell them, mend their manners, or Thomas More will get hold of them and shut them in his cellar. And all we will hear is the sound of screaming.

‘Now, Thomas.’ He looks up. ‘Do you have any Spanish?’

‘A little. Military, you know. Rough.’

‘You took service in the Spanish armies, I thought.’

‘French.’

‘Ah. Indeed. And no fraternising?’

‘Not past a point. I can insult people in Castilian.’

‘I shall bear that in mind,’ the cardinal says. ‘Your time may come. For now … I was thinking that it would be good to have more friends in the queen's household.’

Spies, he means. To see how she will take the news. To see what Queen Catalina will say, in private and unleashed, when she has slipped the noose of the diplomatic Latin in which it will be broken to her that the king – after they have spent some twenty years together – would like to marry another lady. Any lady. Any well-connected princess whom he thinks might give him a son.

The cardinal's chin rests on his hand; with finger and thumb, he rubs his eyes. ‘The king called me this morning,’ he says, ‘exceptionally early.’

‘What did he want?’

‘Pity. And at such an hour. I heard a dawn Mass with him, and he talked all through it. I love the king. God knows how I love him. But sometimes my faculty of commiseration is strained.’ He raises his glass, looks over the rim. ‘Picture to yourself, Tom. Imagine this. You are a man of some thirty-five years of age. You are in good health and of a hearty appetite, you have your bowels opened every day, your joints are supple, your bones support you, and in addition you are King of England. But.’ He shakes his head. ‘But! If only he wanted something simple. The Philosopher's Stone. The elixir of youth. One of those chests that occur in stories, full of gold pieces.’

‘And when you take some out, it just fills up again?’

‘Exactly. Now the chest of gold I have hopes of, and the elixir, all the rest. But where shall I begin looking for a son to rule his country after him?’

Behind the cardinal, moving a little in the draught, King Solomon bows, his face obscured. The Queen of Sheba – smiling, light-footed – reminds him of the young widow he lodged with when he lived in Antwerp. Since they had shared a bed, should he have married her? In honour, yes. But if he had married Anselma he couldn't have married Liz; and his children would be different children from the ones he has now.

‘If you cannot find him a son,’ he says, ‘you must find him a piece of scripture. To ease his mind.’

The cardinal appears to be looking for it, on his desk. ‘Well, Deuteronomy. Which positively recommends that a man should marry his deceased brother's wife. As he did.’ The cardinal sighs. ‘But he doesn't like Deuteronomy.’

Useless to say, why not? Useless to suggest that, if Deuteronomy orders you to marry your brother's relict, and Leviticus says don't, or you will not breed, you should try to live with the contradiction, and accept that the question of which takes priority was thrashed out in Rome, for a fat fee, by leading prelates, twenty years ago when the dispensations were issued, and delivered under papal seal.

‘I don't see why he takes Leviticus to heart. He has a daughter living.’