Полная версия

Полная версияRomantic Ireland;. Volume 1/2

The modern novelists have given us more than our due share of localized Irish. Mr. George Moore, among all their number, spares us the false, perverted language which some are wont to admire, fondly believing it to be of the earth earthy. For not attempting or perpetrating Irish dialect upon us we should all be grateful to Mr. Moore.

In Moore’s books you meet with no such monstrosities as “praste” for priest, “quane” for queen, “belave” for believe, or, worst of all, “yez” for you. Another overworked word in the vocabularies of most writers of Irish fiction or narrative is sure (usually spelt “shure”). Thackeray is supposed to have understood its use better than any other, and as an example one may cite Miss Fotheringay, when she said, “Sure, I made a beefsteak pie.” The “divil” comes frequently to the fore in Irish conversation, or at least there are those who would have us so believe, but its use is more often a perversion than not.

It is well recognized that no one laughs so heartily at the attempt to revive the old Irish language as the modern Celt himself. An anecdote has recently gone the rounds that in literary Dublin, which has for its gods Yeats and George Moore, some one has recently made a printed announcement in Erse, but attached thereto, as a sort of sub-section, is a further admonition in the supposedly much hated Anglo-Saxon.

An intrepid individual once tried his small store of Gaelic on a native, who replied that he did not speak French, though from his appearance, his age, particularly, he was naturally (sic) thought to be one of those who still spoke the venerable tongue of his race.

An Irish automobilist, who had lost his way at a cross-roads because of an enigmatic sign-board, spent much time in roundly cursing the language of his fathers as being entirely worthless and incomprehensible.

Many have taken a grim inquisitorial pleasure in showing to a likely Irishman something written in Erse characters and demanding a translation, which, of course, they could not get.

Occasionally one sees in the Irish daily papers a picturesque Greek-looking inscription, but few know what it means save the perpetrator, who probably copied it from some old phrase-book. “Ceade mille Failthe” we all know, but there our knowledge ends.

All this proclaims loudly the fact that the common people – the middle class, if you like, or what is known elsewhere as the middle class – care and know very little of the motive which inspires the profound scholars of Ireland’s ancient tongue to seek to perpetuate its use.

Since, however, Celtic art is the fad of the day, it is but natural that the Celtic tongue should claim some share of attention; but to expect it to make any serious inroads in the national life, or, indeed, in the lives of the “transplanted Irish” of America and elsewhere, is sheer folly. It were easier to have hoped for the success of Volapuk, which, itself, a dozen or more years ago, died of its own sheer weight of consonants.

Now that Ireland is supposedly prospering at the hands of a solicitous foster-mother, the “Board of Agriculture,” the demand for Irish products and the interest in Irish art and history are undoubtedly increasing. So, too, the interest in Irish literature, in the abstract; but the Irish tongue itself has a poor chance for popularity.

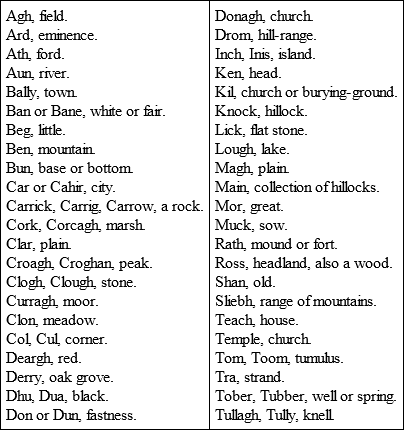

It is well to recall that the mass of the Irish people speak the English tongue alone, a tenth part, perhaps, being able to speak both Gaelic and English, with but a very few who know Gaelic alone. In the south and west the latter is much more spoken than in the north and east, where it is fast disappearing. The Irish Gaelic, or Erse, resembles both the Scottish and the Welsh Gaelic. Some common words frequently met with in travelling about Ireland are:

In the little country towns, where the blue cloaks gather thick upon the platforms of the stations, the musical Irish tongue begins to sound. “To swear in, to pray in, and to make love in,” Irish has no rival among languages dead or living. There are twenty ways and more of saying “darling,” and at least as many ways of sending a man to the devil. When the Saxon coldly orders an enemy to “go to the devil,” the Celt fiercely breathes the wish, “May the devil sit upon your breast-bone, barking for your soul!” and the “Go and hang yourself!” of the Englishman becomes “The cry of the morning be upon you!” – embodying in this brief sentence a detailed wish that the enemy may die a sudden and unprepared death in his bed, and that his relatives, entering in the morning, may find him dead, and shriek over his remains. It is a picturesque and forcible tongue, most assuredly, though one needs a glossary and a thesaurus to correctly estimate the values of these pet phrases.

The various blended emotions and sentiments current everywhere in Ireland are the product of tradition in which legend and superstitious belief play an important part. They may not actually enter into every hour of one’s life, but they are ever-present and the supply is bountiful.

George Moore has said that every race has its own peculiar genius. “The Germans have music; the French and Italians have painting and sculpture; the English have, or had, poetry; and the Irish had and still have their special genius for the religious vocation.”

There is no more popular legend or superstition in Ireland, unless it be that of the Blarney Stone, than that referring to St. Patrick’s having driven the snakes from the country. According to the report of tradition, nothing venomous is ever brought forth, nourished, or lives in Ireland. Naturalists do not, however, agree with this.

The Venerable Bede evidently believed it, and that the freedom of Ireland from venom was due to the efficacious prayers of St. Patrick.

Another authority (Keating) remarks it, and finds it due to a prophecy of Moses that wherever his posterity should inhabit, the country would not be infested with poisonous creatures. The superstition is already hoary with age, but is a perennial topic of conversation and source of argument with the natives in all parts.

The literary associations of Ireland are so numerous and of so fresh a character as to suggest the compilation of a great, if not an exhaustive, work on the subject. At any rate, they are too voluminous to record here, even though the geniuses of Swift, of Lover, of Goldsmith, and of Moore stand out as if to compel attention, as they certainly do, in the same convincing manner that Swift’s “Gulliver” influenced a certain Irish bishop, who accepted the tale as the truth, “although not a little amazed at some of the things stated.”

Writers on early Irish literature have often overlooked or ignored the fact that, besides the chroniclers of fame and note who indited learned historical works or majestic verse, there are, too, existing poems by various ladies of early Ireland, generally daughters of kings. Another Meave, called the Half-red, has some of the characteristics of Queen Meave herself: “The strength and power of Meave was great over the men of Erinn,” says the introduction to her poem over the grave of her first husband, whom she deserted for a better man; for it was she that would not permit any king in Tara without his having herself as wife.

“My noble king, he spoke not falsehood;His success was certain in every dangerAs black as a raven was his brow,As sharp was his spear as a razor,As white was his skin as the lime.Together we used to go on refections;As high was his shield as a champion,As long his arm as an oar;The house prop against the kings of Erinn sons of chiefs,He maintained his shield in every cause.Countless wolves fed he with his spear,At the heels of our man in every battle.”Ireland’s daughters must have been a glorious and mighty race; indeed, they are so to-day, and one does not need to go back to Moore for endorsement, though he contrasts with marked effect the native elegance of Erin’s daughters with the affected fashionable city belle:

“Lesbia wears a robe of gold,But all so close the nymph has laced it,Not a charm of beauty’s mouldPresumes to stay where nature placed it.Oh! my Nora’s gown for me.That floats as wild as mountain breezes,Leaving every beauty freeTo sink or swell as Heaven pleases.Yes, my Nora Creina dear,My simple, graceful Nora Creina,Nature’s dressIs loveliness —The dress you wear, my Nora Creina.”This was doubtless true enough in Moore’s time, and is so to-day, in spite of the fact that they no longer stand picturesquely around and display their charms in just the manner expressed by the poet.

One hears frequent references to the laureate Spenser’s life in Ireland, of his verses in praise of its charms, and of his undoubted love for it, which certainly was as great, if different, as that of Ireland’s recognized “national poet.” Irish sentiment has never allowed recognition to Spenser’s accomplishments, however. The Irish themselves, who are always ready to turn the dull side of the gem toward the light, are not in complete accord on the question of Spenser’s love for Erin, as one will infer from the following, taken from “A Brief Account of Ireland and Its Sorrows:”

“Among those who lived here was Spenser, a gentle poet but a rapacious freebooter. His poesy was sweet and full of charms, quaint, simple, and eloquent. His politics were brutal, venal, and cowardly. He wooed the muses very blandly, living in a stolen home, and philosophically counselled the extirpation of the Irish owners of the land, for the greater security of himself and fellow adventurers.”

The above is but a note in the gamut, but it is a true one, and it does not ring false, and, while the moral aspect of Spenser’s right to his livelihood in Ireland is left out of the question here, one can but feel that if the Irishman were less emotional and more forgiving much would come to him that he now lacks.

CHAPTER V.

RELIGIOUS ART AND ARCHITECTURE

IT has been claimed that Ireland has no distinctive art or architecture, and that the venerable ruins of monasteries and churches, the stone crosses, the curiously interwoven traceries of stone carving, the illuminated manuscripts, and even the famous round towers themselves were all transplanted from a former home; and that the jewelry, bangles, brooches, and rings, which we fondly believe are Celtic, are nothing more than Byzantine or Eastern motives, which found their way to Ireland in some unexplained manner.

Whether this be acceptable to the average reader or not, whether he remarks the similarity between certain of the Celtic (?) motives and similar decorative effects in wood and stone known to belong to the Northmen, or whether he prefers to think them an indigenous growth and development of Ireland itself, matters little, in a broad way.

Nowhere but in Ireland are there so splendidly executed and preserved traceries of the peculiar sort which is shown in the crosses at Kells and Monasterboice, and, in manuscript, in the “Book of Kells.” Nowhere are there more numerous or more gracefully proportioned round towers than in the Emerald Isle, and nowhere are there more consistently and thoroughly expressed Norman and Gothic forms than in the many ecclesiastical remains which exist to-day, though many of these establishments have not the magnitude or splendour of others elsewhere.

The palaces of the Irish kings would have, perhaps, the chief interest for us to-day, did they but exist in more tangible form than reputed sites and mere heaps of stones. From the chronicles we know that they were splendid residential establishments, but not much more.

The chief of the palaces whose splendours are celebrated in Irish history were the Palace of Emania, in Ulster, founded or built by Macha, queen of Cinbaeth the First, about the year B.C. 700; Tara, in Meath; Cruachan, in Conact, built by Queen Meave, the beautiful, albeit Amazonian, Queen of the West, about the year B.C. 100; and Ailech, in Donegal, built on the site of an ancient sun-temple, or Tuatha de Danaan, fort-palace.

Kincora had not at this period an existence, nor had it for some centuries subsequently. It is said to have never been more than the local residence, though a palatial one, of Brian Boru.

Emania, next to Tara the most celebrated of all the royal palaces of ancient Erin, stood on the spot now marked by a large rath called the Navan Fort, two miles to the west of Armagh. It was the residence of the Ulster kings for a period of 855 years.

The mound or Grianan of Ailech, upon which, even for hundreds of years after the destruction of the palace, the O’Donnells were elected, installed, or “inaugurated,” is still an object of wonder and curiosity. It stands on the crown of a low hill by the shores of Lough Swilly, about five miles from Londonderry.

Royal Tara has been crowned with an imperishable fame in song and story. The entire crest and slopes of Tara Hill were covered with buildings at one time; for not only did a royal palace, the residence of the Ard-Ri (or High King) of Erin, stand there, but, moreover, the legislative chambers, the military buildings, the law courts, and royal universities surrounded it. Of all these nought now remains but the moated mounds or raths that mark where stood the halls within which bard and warrior, ruler and lawgiver, once assembled in glorious pageant.

The round towers of Ireland form a subject of curious and speculative interest to him who views them for the first time, as, indeed, they do to most folk, learned or otherwise. The actual invention and construction of these round towers are clothed in much darkness. It had previously been supposed that these extraordinary erections were the work of the Danes, but this position seems to be entirely untenable on many grounds, the chief being that no similar structures exist, or probably ever have existed, in the native country of the Danes, and are, indeed, notably absent from many parts of Ireland where the Danes are known to have been, and yet are found in other localities which were never occupied by the Danes.

The great question with regard to these lone towers is whether or no they are, or were, Christian structures. No such monuments are found elsewhere in the known world, except in India or Persia, where, manifestly, their inception was not due to Christian influences.

In a way, a very considerable way, they resemble the minarets and turret towerlets of a Cairene or Damascene mosque, where often, in the smaller mosques, at least, the sky-piercing pointed towerlet is the chief and most imposing part of the structure.

They may have been signal-towers; they may even have been refuges, though they could not shelter any very great numbers, save in the buildings which often flocked around their bases. In this case they performed much the same functions as the watch-tower or turreted donjon-keep of a castle. At any rate, they were of profound moral and significantly Christian motive, rather than pagan, as he who reads may know.

The power of the Church in Ireland grew as it did elsewhere, in France in particular, largely from the foundation of those great secular religious bodies, the abbeys and monasteries.

From the time when St. Patrick – carried in slavery from Scotland to Ireland, and subsequently escaping – returned to Ireland in 430-432 to convert the island to Christianity, to the present day, is a long period for any particular institution to have survived and still continue its functions in the same abode. For this reason it is unreasonable to suppose that there is much more than tradition, however well supported, to connect the personality of St. Patrick and his immediate successors with any edifices, however humble or fragmentary, which exist to-day. If they do exist, as popular report would seem to indicate, they most likely are rebuilt structures upon the reputed ancient sites, with the bare possibility that somewhere, down in the cavernous depths of their underpinning, exist the stones of wall and pavement which may have known these early pioneers of Christianity. The art and influences of Christianity, both in Ireland and Scotland, are, from the sixth century, at least, similar as to the development. This was but natural, considering that its great impetus in Scotland only came in the sixth century with the advent of St. Columba, an Irish monk, who was exiled from his own country in 563, and who, coming to Iona at that time, founded a monastery there, and thence passed over to the mainland of Scotland.

In France, about 646, Arbogast, an Irish monk, founded an oratory, and Gertrude, the daughter of the illustrious Pepin, sent to Ireland for “further persons qualified to instruct the religieuse of the Abbey of Neville, not only in theology and pious studies, but in psalm-singing as well” (“Pour instruire la communate dans le chant des Pseaumes et la meditation des choses saintes.”). Charlemagne, too, placed the universities of Paris and Ticinum under the guidance of two Irishmen, Albin and Clements, who had previously presented themselves, saying that they had learning for sale.

The “Monasticum Hibernicum” enumerates many score of abbeys, priories, and other religious establishments in Ireland.

One is inclined, in this progressive age, to marvel when he contemplates the universality, among all nations, of that religious zeal which drew its thousands from the elegance and comforts of all classes of society to the sequestered solitude of monastic life.

Its history is well known and it is generally recognized that, as the enthusiasm of the Crusades subsided, many influences, which otherwise made for the aggrandizement of the religious orders, became, if not negative, at least impotent.

There were, perhaps, some solitaries in the third century, but it was not till after the conversion of Constantine, A. D. 324, that the practice of seeking seclusion from the world became general.

Monasticism came to Rome, where St. Patrick received his inspiration, from Egypt, and made its way into Gaul, the monks of St. Martin’s time reproducing the hermit system which St. Anthony had practised in Egypt. Gallic monasticism, during the fifth and sixth centuries, was thoroughly Egyptian in both theory and practice.

St. Benedict, the founder of Western monasticism, was born about A. D. 480, and began his religious life as a solitary; but when, early in the sixth century, he “wrote his rule,” “it is noteworthy,” says a French authority, “that he did not attempt to restore the lapsed practices of primitive asceticism, or insist upon any very different scheme of regular discipline.” His rule was dominated by common sense, and individualism was merged in entire submission to the judgment of the superior of the house.

Ireland was in the very forefront of the movement, though St. Patrick’s monkish possessions here did not take shape until well into the fifth century; but it was about fifty years, more or less, – authorities differ, – after St. Benedict’s death that Augustine arrived in England (A. D. 597). He and his monks introduced the “Rule” into England. Celtic monasticism did not greatly differ from Western monasticism, which under many names, and with many variations in detail, ever since St. Benedict’s time down to our own day, has been Benedictine at bottom.

Congal, Carthag, and Columba continued in St. Patrick’s footsteps, in the sixth century, and carried monastic life to still greater splendour and perfection by their rules and foundations. Then followed throughout Ireland, in a long and splendid succession, many Augustinian, Benedictine, and Cistercian foundations.

Besides their glorious ecclesiastical monuments, these bodies were possessed of great wealth in lands, and even in gold. In fact, public generosity, and the opulence of the communities which sheltered them, gave them an almost supreme power, and from obscurity they rose to be all-powerful factors in the life of the times.

The prostrating fury of the Reformation moved more slowly here than in England. Ireland had no Wyclif to raise his voice against Rome, and the people in general were, and wished to be, passive subjects of the sovereign pontiff.

The Augustinians exceeded in numbers those of any other order in Ireland, but the Arrosians, the Premonstratensians, the Benedictines, the Cistercians (a branch of the Benedictines), the Dominicans (founded by St. Dominic, a Spaniard born about 1070), and the Franciscans (founded by St. Francis of Assisi), and various other orders, were also well established.

In addition, the military orders were likewise represented by the Knights Hospitallers, or Knights of St. John, and the Knights Templars, so called from the fact of their original home having been near the Holy Temple.

The heads of the monastic houses were the abbot, who governed the abbey, and whose possessions were often so great, in Ireland, as to entitle him to a seat in the parliament amongst the peers; the abbess, who presided over her nuns in much the same manner as the abbot governed his monks; and the prior, who was often the head of a great monastic foundation, and many of whom also had seats in Ireland’s parliament.

The military order of Knights Hospitallers also were builders, erecting castles on their manors, such establishments being known as commanderies, while the knight who superintended was styled preceptor, or commendator. Whenever the Knights Templars followed this example of the Knights Hospitallers, their castles were called preceptories.

The almoner had the oversight of the alms which were daily distributed; the chamberlain the chief care of the dormitory; the cellarer procured the provisions for the establishment; the infirmarius took care of the sick; the sacrist was in charge of the vestments and utensils, and the precentor, or chantor, directed the choir service.

Throughout Ireland, too, were erected many hospitals, friaries, and chantries, for the most part presided over and controlled by members of the higher orders. The friaries had seldom any endowments, being inhabited only by mendicants. Chantries were endowments for the maintenance of one or more priests, who were to daily say mass for the souls of the founder and his family. There were formerly many such in Ireland, usually connected with the larger churches. Hermitages were obviously devoted to the residence of solitaries who secluded themselves from the world and followed an ascetic life of confinement in small cells.

This brief résumé is given solely from the fact that it is a commentary on many references which are made elsewhere in this volume, and not in any sense as an assumption that these facts are not otherwise readily accessible to the general reader.

It shows, moreover, that monkery was cultivated in Ireland as zealously, and to as great an extent, as in any other nation in Europe, and in addition had, for centuries, supplied many brethren to other establishments throughout the known world, notably to seminaries at Rome, and in Spain, Portugal, and the Low Countries.

At the time of the Revolution the number of “regulars” in Ireland was above two thousand, and these all in addition to the regular ecclesiastical establishment and its clergy.

The mere attempt to define and describe the cathedrals of Ireland as they exist to-day, or as they existed at the disestablishment, in a work such as this, would be fated to disaster from the very first lines.

No brief explanation, even, as to why their numbers were so great, their size so attenuated, or their architectural qualifications so minor, would be satisfactory, and for that reason they must, as a class, be dismissed with a word.

The minor county cathedrals of Ireland are almost unknown to all but the historian and archæologist.

The larger and more important examples – as in Dublin, Kilkenny, and Cork – are possessed of considerably more than a local repute, though none are architecturally pretentious or great, as compared with the cathedral churches of England or the Continent.

The cathedrals of Ireland are in many instances commonplace little countryside churches, insignificant and inaccessible, and many of them, in fact, of no great age or beauty; but they claim, rightly enough, along with many more ambitious edifices elsewhere, the proud distinction of once having been cathedral churches.

The largest and most splendid is St. Patrick’s at Dublin. Kilkenny, which next approaches it, falls considerably short of it in size; while St. Patrick itself takes a very low rank indeed as compared with England’s noble minsters.