Полная версия

Полная версияRomantic Ireland;. Volume 1/2

What the further and yet dimmer future will be, no one can tell; but the above seems a plausible opinion which has much to justify it, both in precedent of the past and with due regard to the racial characteristics of the people.

Others hold out more hope. The Right Hon. George Wyndham, M. P., chief secretary for Ireland, stands sponsor (1903) for the fact that it is the wish of the people at large that “the evening star of the Empire, shedding a sad light in the west, shall rise toward the zenith and shine out from amid the brightest constellations in the imperial empyrean.”

With Mr. Wyndham’s appointment to the secretaryship, it is thought by many Ireland’s great revival is at hand.

Already opposing partisans have begun to realize that the genius of the Celt disposes the Irish to take kindly to coöperative efforts for their welfare; and more stimulating than all else will be found to be the great Celtic revival among all classes.

Forty years ago the great Protestant revival in Ulster had for its object, or at least its main object, a passionate and more or less selfish personal aspiration.

To-day the movement is even greater, while it leaves religion aside, and is essentially national.

Study has taken the place of idleness; grammars have replaced playing cards. On St. Patrick’s Day the Irish celebrate the restoration of their ancient language to its ancient dignity. The public-houses are shut up instead of being crowded. A new hope, a new motive, a new incentive, – all these are visible in Ireland. They find practicable expression in the enthusiasm with which the Irish language is being studied everywhere.

This latter may be a pure fad, but it is in no way an unhealthy one. How far the chief secretary’s attitude actually goes in behalf of Ireland, his own words will best tell.

In the House of Commons he asked:

“Was it necessary to dread any dire political consequences from the spread of the Celtic renaissance? He thought the object, the brightening of the intellect of the Irish child, was a good one; and he did not think the political consequences would be very harmful. If, as a result of such instruction, Irish lads in fifty years gave up the practice of singing, on certain anniversaries, inspiring ditties which enjoin the propriety of kicking the Crown or the Pope into this or that river, and preferred to sing the Irish song:

“ ‘Oh! where, Kincora, is Brian the great,Where is the beauty that once was thine,Where are the princes and nobles that sateTo feast in thine halls and drink the red wine?’he could not see that the change would be politically deleterious. They could not make a Scotsman into a better engineer by confiscating his heirloom; and their language was an heirloom of the Irish. Its usefulness was not immediately obvious; but that was true of most household gods, and yet a tutelary reverence for household gods had often nerved heart and hand for utilitarian contests. There was no heresy to the Union in permitting to Ireland that which they promoted in Scotland and in Wales; on the contrary, it was an article of the Unionist creed that within the ambit of the Empire there should be room for the coöperation of races, maintaining each its memory of its own past as a point of departure for converging assaults on the problems of the future.”

There can be no doubt but that the chief secretary for Ireland has been baptized with the spirit of the Irish revival. He believes in Ireland. He loves the Irish people. To him the witty and mercurial Celt is much more sympathetic than the more stolid Englishman. Ireland, like the fair damozel in Spenser’s poem, has a singular fascination for the Sir Calidores and Sir Artegalds who stray within range of the magic of her charms.

As to what were the real beginnings of Ireland, and whence came the original Celt, we must for a time longer, it seems, remain in doubt. The more the pity, for the character of a people is in large measure due to inheritance. Here, for centuries long gone past, there was isolation in manners, customs, and forms of government. But then, Ireland being insular, the chances were that many people of a different race might have mixed their blood with that of the early settlers. Still, there never was a country which delighted more in legends and of which the past was more legendary. And, above all, the Irishman always respects these antiquated stories, whether authenticated by later scholarship or not.

Therein lies the charm of association which surrounds the very shores and rocks and rills of Ireland.

Here are a few brief lines from McCarthy which express it far more succinctly and with more feeling than it would perhaps be possible for any other living historian to write, be he Irishman or not:

“Every stream, well, and cavern, every indentation of the seashore, every valley and mountain peak, has its own stories and memories of beings who did not belong to this earth. A distinguished Englishman once said that whereas in the inland counties of England he had found many a peasant who neither knew the name of the river within sight of his cottage, nor troubled himself about its early history, he never met with an Irish peasant who was not ready to give him a whole string of legends and stories about the stream which flowed under his eyes every day.”

An American writer, Horatio Krans, has recently attempted to dissect the motives of the Irish novelist of the first half of the nineteenth century. He has put his finger upon one notably weak spot in the earlier novels, – the delineation of female character. He claims particularly (though the Irish novelist is not alone in this sinning) that the heroines, with a few exceptions, – Lady Geraldine in Miss Edgeworth’s “Ennui” and Baby Blake in “Charles O’Malley,” – are hopelessly conventional in speech, in sentiment, and in manner; all of which is undeniably true.

The Irish novelists of the time divided their product into two distinct classes, “the novels of the gentry” and “the novels of the peasantry,” and there is, as a fact, much in favour of the heroine of the peasantry class.

The names of the novelists of that time most generally known, and most readily recalled, are unquestionably, first of all, Goldsmith, then perhaps Miss Edgeworth, Charles Lever, Maxwell, and Samuel Lover. Among themselves they have apportioned the various types which we of a later generation have come to recognize as of the soil. The most notable, and one common to all, is that strange product of Irish life (to which, it may be observed, Oliver Goldsmith called attention), the “squireen,” who was without an idea beyond a dog, a gun, and a horse.

It is a commonplace to remark here that many of the gentry of that time lived in barbaric and slovenly splendour, led devil-may-care lives, hunted during the day, and drank, played cards, and quarrelled at night.

But new forces are certainly bestirring themselves in the Ireland of to-day, and a new standard of life, a wider knowledge, and a finer culture is broadcast. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the realm of Ireland’s imaginative literature, in prose as well as verse.

Of the actual life of the times, the present-day Irish novelist draws not with so firm a hand as his predecessor, but he makes a more pleasing picture.

The duel, as an institution, is extinct to-day, but much the same mode of life as that of a former day is depicted in the stories of Miss Sommerville and Miss Martin Ross. In these modern novels are found the horse-dealing, hunt-loving gentry; but the peasants appear only as retainers and as necessary adjuncts to the occupations of their betters. The Ireland of these writers, then, is a land of happy-go-lucky and thriftless enjoyment and cheerful impecuniosity, with an occasional glimpse of tragedy. Miss Katherine Tynan, too, deals with the same class and succeeds in depicting Irish landscape, in its quick-changing colours, its gloom and sunshine strangely mingled, mountain and bog, dew and rain, in a manner which suggests that her books are a genuine distillation of Ireland itself.

The soul of a country is to be sought in the literature of the people, and the literature of Ireland is yet, to the vast majority, an unopened book; and, paradoxically, it is in the pages of fiction that one seeks a record of many facts which are otherwise unwritten.

Besides the “gentry” and the “peasantry,” the two distinctive classes into which writers divide the Irish, there is another class in Ireland, and an important class, which has been practically neglected by Irish writers of fiction, – the shopkeeper. Here Ireland is at once the most aristocratic as well as the most democratic country in the world. In the learned professions you will find the sons of butchers and publicans jostling the offspring of peers and gentlemen of lineage in the race for preferment, and, like enough, beating them at their own game. In England the expected sometimes happens; in Ireland even the fairy-tales may come true; and there will be found a delicate refinement in life which, those competent to explain suggest, has been imported by the daughters of the house from the convents of Ireland, of France, and of Belgium.

Few countries so small have given the same opportunities to the novelist as has Ireland. Village life is dull enough from within, no doubt; from without, unlike English village life, it is, in Ireland, quite dramatic. It has been said that the people are unconsciously dramatic and that even their grief is picturesque. The possibilities of the race are great.

An Irish villager may become a Dublin shopkeeper, a London barrister, or, in America, a politician of the first rank. He would never once so much as get a glimmering of this in his native village; but news of the outside world filters through and attracts the ingenious and soulful Irishman to the betterment of himself, and, truly enough, in many cases no doubt, to the poverty of Ireland; for it has come to be admitted that the desertion of Ireland by those who have since become classed among the world’s great is one of the plausibly acceptable explanations of Ireland’s poverty.

Every French soldier was said to carry the field-marshal’s baton in his knapsack. Every Irish peasant who crosses the Atlantic has his marshal’s baton in his knotted handkerchief on the end of his blackthorn. It is a young race in modern development; its energies are fresh and unexhaustible, and therein lies a field for the novelist which is not yet worked out.

One other type should be mentioned here, if only to proclaim their unselfish devotion to their vocation, – that of the parish priest, the poor cleric who, with a parish of a few score of souls in some barren bog, finds his life-work full in ministering to their souls, and often, as well, to their bodies.

The pseudo-Irish priests of melodrama, and too frequently of novels, are huge travesties on the devoted and valiant fathers who are hidden away in innumerable corners of Ireland, surrounded only by a dwindling score of communicants.

The Ireland with which the present-day traveller has most to do is the Ireland which came more or less under English influences in the time of Henry II.

The legendary and romantic period of the Phœnician settlers, the Spanish colonists, and the warfares of petty kings and chieftains has left little but a vague impress upon Irish national life and sentiment, if we except a certain imaginative and romantic temperament, which seems to be the true birthright alike of the Irish poet, peasant, and politician.

The crafty, ambitious Henry obtained from Adrian II., the first and only English Pope, in 1159, a bull authorizing him “to enter Ireland and execute therein whatever should pertain to the honour of God and the welfare of that land.”

English power in Ireland rooted, grew, and flourished, and propagated no end of internal troubles, which are to this day, if we are to believe all that we see and hear, the cause of much of Ireland’s unrest.

During four centuries Ireland was visited by but three English sovereigns, Henry II., John, and Richard II., and during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries English influences gradually declined, reaching their lowest ebb at the time of Henry VII. The Reformation, under Henry VIII., took place in 1536, and was in all respects the most remarkable era of Ireland’s history, and from that time on – until the events which rose out of the tenantry laws, and home rule, and their attendant and satellite conditions – her troubles have been solely a warfare more or less dependent upon religious influences and conditions.

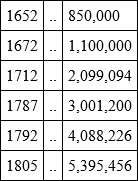

Commencing with the seventeenth century, the population sprang forward with leaps and bounds. Its estimated growth for the succeeding two hundred years is as follows:

According to the old historians, there were anciently many divisions of Ireland, made at various times by the several petty kings and chiefs who had possession of them.

There is an element of uncertainty about all the information concerning these ancient political divisions; some, indeed, may have been purely apocryphal, hence writers have mostly contented themselves with defining and delimiting the more modern divisions of Ulster, Leinster, Munster, and Connaught.

These four great divisions were subdivided into thirty-two counties, 256 baronies, and 2,293 parishes.

The province of Ulster took in the northern part of the island, and extended from sea to sea. What has always rendered this province superior, in prosperity, to the rest of the island is its great industry of linen manufacture.

The province of Leinster, in which is situated Dublin, Wicklow, etc., has the sea only on the east. The writers of a century or more ago were prone to remark that here the inhabitants approached the nearest to English manners and customs, and with some truth this is so.

The province of Connaught, with the sea on its western boundary, containing the counties of Mayo, Galway, and Sligo, through the city of Galway early arrived at a commercial prominence which later eras have not sustained.

Munster crosses the southern part of the island, extending itself northward on both the east and west coasts. Its principal and most famous city is Cork, and the whole county abounds in that wild romantic scenery which has fondly inspired so many poets and painters.

To these four provinces some ancient writers added a fifth, called Meath, formed by a small part taken from each of the other provinces, but independent of all of them.

Of the ancient commerce of Ireland Tacitus wrote: “Its channels and harbours are better known to merchants than those of Britain,” which eulogy, of course, referred to the first century.

The Phœnicians are reputed to have worked the mines which existed in the neighbourhood of the lakes of Killarney, and to have acquired the art of “extracting the celebrated Tyrian purple from the juice of shell-fish.”

Cæsar’s invasion of what are known as the British Isles was supposed to have been instigated by the export from Ireland of the “margaritas” taken from these Killarney mines.

That the commerce referred to by Tacitus was that carried on by the Phœnicians, is deduced from the fact that the Romans knew nothing of the country at that time.

CHAPTER IV.

ROMANCE AND SENTIMENT

THE ingredients which most writers on Ireland, the historians, the antiquarians, the political agitators, the publicists, the poets, and, last but not least, the fictionists – from the days of Samuel Lover to George Moore and Bernard Shaw – have used as a basis for their written word have been many and varied.

Some have pictured it as a land of desolation and poverty, rich in nothing, while others have descanted elaborately upon its treasures and wealth of historical, architectural, and ecclesiological remains; the beauty of the literature of its native legends; its poetry and music; and erstwhile its native tongue, which may have a latent charm to those versed therein, but which will never become a popular speech, as an Irish member must have hoped when he recently attempted to make a speech therein in the British House of Commons.

No one but an encyclopedist could hope to embrace, within the confines of a single work, a tithe of the accessible material which should contribute to the making of an exhaustive work on the subject, and the monumental work is as yet unwritten, and, for aught the present writer knows, unplanned.

Perhaps the more interesting detail of any picture which attempts to limn the outline of an Irish landscape, is that which unmistakably indicates the unique character of the inhabitant himself.

There may live an Irishman without humour, without sentiment, without “wrongs;” men and women who marry early, without love, and settle down to a hopeless life of dreary toil, too discouraged to even resent the misery of their lot; but, if so, it is in the pages of the novelist. Those who have in them anything of the real native spirit of youth and courage emigrate, a procedure which, however, deprives the country of much of its soundest raw material. George Moore ascribes this condition to the Irish clergy, who cripple their parishioners with taxes to build unnecessary churches, and who crush out of them all the joy of life by an enforced asceticism.

But all that is decidedly another story and quite apart, and is really not so obvious as is at first apparent. The real, genuine Irish peasant is not found, to-day at least, in the pages of the novelist, nor in the verses of the poet, nor in the songs of the opera-house. Tom Moore pictured him with some of the truthfulness of the time, and there is a realization of certain well-recognized local sentiment and colour in “Kathleen Mavourneen.” In the main, however, the joyous Irish peasant, as full of wit as of knavery; the poetic Irish peasant, living in an atmosphere of quaint legend and of charming superstition; the political Irish peasant, member of the Land League, and noble patriot, or treacherous ruffian, according to the attitude which we take toward the Irish question; the romantic Irish peasant, warbling cadences to the faithful girl of his heart, does not exist, – at least he does not in sufficient numbers to project himself into view at every turn, as he does in the comic-opera chorus and the pages of the humourous (sic) Irish tales of to-day.

Romance and legend have associated the shamrock, the shillalah, and the dudeen with nearly every mood of Irish fact and fancy; but the casual traveller and seeker after new sensations will see little of any one of these three more or less visionary attributes of the landscape in general. To be sure, if he insists on being brought at once under the spell of the environment which he has pictured to himself as being the one universal accessory of every patch of the “ould sod,” or of every gathering of its inhabitants, he will, if he goes to the right places to look for them, discover the whereabouts of most things of this world’s civilization, of all eras, from the stone hatchet of the ancient Celt, to the motor-bicycle of the Dublin barrister out on a holiday; and from the rancorous peat-bog with its cave-like habitation and straw-bedded floor, to the damask and fine linen of the last joint-stock enterprise of the hotel-keeper, in such advanced centres of progress as Dublin, or more particularly Belfast.

If he takes his standard of judgment from the view-point of food for man, he will find it, in some remote and more poverty-stricken localities, to be something very akin to what he has always believed to be mere fodder for beasts; and again, in the aforesaid luxurious caravansaries, to be the same as that which grace the average tables d’hôte of the great establishments the world over, be they situated in Paris, Vienna, London, or San Francisco.

The “Green Isle” is always green, and the native is always picturesque. Sometimes, far away from the centres of population, he is dirty, but not offensively so, at least, not more so than the Italian or Spaniard under similar circumstances.

What memories are conjured forth, even to the untravelled, by the mere mention of such places as Killarney, Cork harbour, or Blarney Castle in the south, or Moville, Londonderry, or the Bloody Foreland in the north; and, to specialize for a moment, who among students of history does not give a deservedly high place, among the things of the world beautiful, to the arts of the early builders of Christian edifices in Ireland?

In all manner of building, theirs was an art-expression as far above that of the pagan Britons in the neighbouring isle as is possible to imagine.

Ireland, indeed, in the sixth and seventh centuries, was the chief centre of Christian activity, of Christian missionary work, and of Christian art in the islands. So strong an influence was this that it is recorded that Irish missionaries went not only afield into England, but even to Italy.

The antiquarian and geologist have proved beyond a doubt – what is easy, however, for even the layman to believe – that the Ireland of to-day was originally merely one of the outlying parts of the mainland, and the expression of the customs and arts of the inhabitants of the two at that time did not then differ greatly one from the other. This was maintained, the scholars tell us, through the neolithic and the bronze ages, at which period Ireland came to part company with the mother island.

The transition came when the Romans occupied Britain. Roman towns sprang up which had no counterparts in Ireland, and usage and custom developed an entirely new condition of life.

Thus Ireland retained a crudity of strength and expression which early evinced itself in its Christian art, and which was added to but slowly.

As to what may have been the early religion of the Irish, we are still in the dark. That there were druidical priests seems probable. Legend says that St. Patrick had been a slave in Ireland, having been brought from Scotland, and that even in his days of slavery he formed an affection for the country and its population. The date of St. Patrick’s coming to Ireland, as a bearer of the gospel, is said to have been in the year 430-432, when he returned from Rome after having escaped his bondage. The difficulty is to understand how, at once, Ireland became Christian and, according to the old traditions the “home of Christianity,” and, on that account, called “the Isle of Saints.”

St. Patrick’s birthplace is much in dispute, and Armorica, Gaul, Scotland, Wales, England, and Ireland contend for the honour. Much wordy warfare has left the question still undecided, but it is of little moment, since the main facts in the life of this holy man are known, and his devotion to Ireland recognized by all.

To come to a latter-day aspect of Ireland, in its relation to world affairs, let us pray that there are signs that the night of hatred and the twilight of suspicion are brightening into a new dawn in partnership between Great Britain and Ireland – into a day of mutual understanding, respect, and, in the end, affection.

To realize all that this means, one must understand something of the peculiarities of the Celtic race and their finer traits, even making allowance for their less amiable qualities. To do this, without too great an expenditure of time, one could hardly do better than to digest Justin McCarthy’s recently published book (1903) entitled “Ireland and Her Story.” He will then be, if ever, in a fit mood for appreciation of the lovable and inspiring qualities to be observed in the land itself, no less than in the inhabitants themselves.

Mr. George Moore, in his play, “The Bending of the Bough,” has attempted to draw a comparison between the temperament and characteristics of two distinct classes, one resident in a town in the Celtic north of Ireland, and the other in the Saxon south of Scotland. The work is a satire, no doubt, but it shows how widely dissimilar are the majority of the representatives of the two races, and should do much to throw additional light on the subject of the alliance of the two nations. When all is said and done, one comes naturally to the opinion that it was the Irish race, of tradition, at least, that gave the major portion of the romance and fairy-lore to European literature in general – excepting, of course, the sages of the Northland. As Mr. Yeats says, though with a pardonable bias, “Daily life has fallen, for the most part, among prosaic and ignoble things, but in our dreams (we) remember the enchanted valleys.”