Полная версия:

Crucible of Terror

For days I had been dreading the sacred reading. Now my stomach was in knots, and my mouth felt like cotton. Behind me, I could feel the presence of the whole community. Like me, they either wore hats or yarmulkes, and some bore on their shoulders the Tallith, a blue-and-white-striped prayer shawl with silver seams and fringes. Some men would take the fringes, touch their personal prayer books, and kiss them each time God’s holy name appeared in the text. I learned that as sinful men, we should not pronounce the most sacred name, written in the four Hebrew letters called the Tetragrammaton. It had to be replaced by Adonai, which means “Lord,” or by Adoshem, which means the “Lord of the Name.” Never should the holy name cross our sinful lips. I used a silver pointer to trace the words from right to left upon the scroll. My reading became confident and fluent. I stepped down to be congratulated by all. I was now a man.

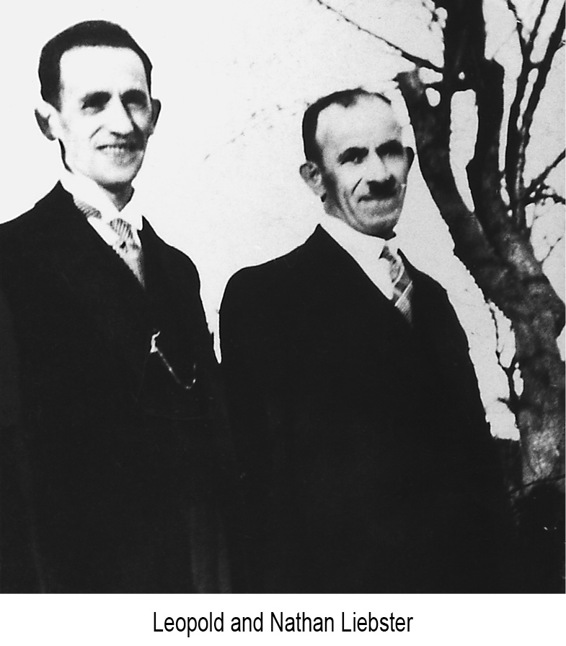

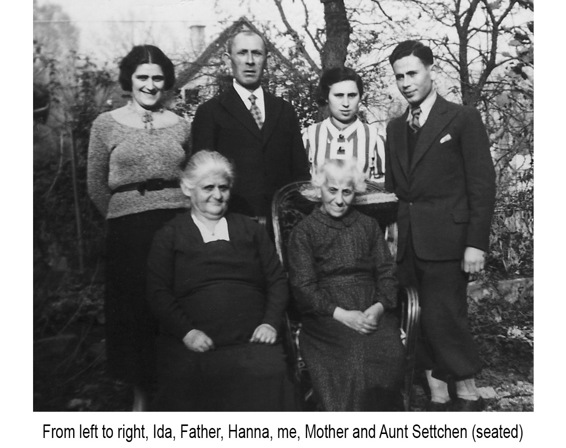

After the ceremony, the rabbi came to our home. As was traditional, we should have had a feast in honor of our special guest and to commemorate my Bar Mitzvah. Instead, the meal was very plain, and the guest list small. Father’s younger brother, Nathan Liebster, a cobbler like him, lived in Aschaffenburg. Nathan and his family were the only ones present for our celebration. Mother’s brother, Adolf Oppenheimer, couldn’t come. He lived in Heilbronn and had a hard time doing the daily chores in his men’s clothing shop. He was sickly; he just could not afford to make the trip. Father’s third brother, Leopold Liebster, a tailor who lived in faraway Stuttgart, had not been invited at all. More than distance separated my father and my uncle. Leopold had married out of our faith. His Catholic wife refused to have her children raised in the Jewish religion. Leopold did not want his children to become Catholics, so they raised the children as Protestants.

My Bar Mitzvah pleased my father, who was a devout man of prayer. My bed stood in the corner of his workshop, among piles of leather skins and shoes. From there, in the early mornings, I watched my father say his prayers. He stood at the foot of his bed, the prayer shawl upon his shoulders, the prayer book in hand, and the Tefillin (passages from the Torah written on parchment and placed in leather coverings) wrapped around his left arm and hand. Leather straps held the little Scripture case that hung on his forehead between his eyes. He chanted parts of the prayer while rocking back and forth. Each time he took the prayer shawl from his shoulder to pull it over his head, I knew that he had encountered God’s holy name. Before Dad started his day, he would daven (pray) for one hour. Even when he had to leave for the city at 4:00 a.m., he never failed to rise an hour earlier to say his prayers.

I would have loved to become a hazzan (cantor) like Grandfather. The villagers always told me that I was the exact image of Grandfather Bär Oppenheimer.

Though I looked like my grandfather, we differed in one respect. I had always been weak around blood. I remembered when I had fainted at the baby’s circumcision so many years ago. My parents may have hoped that I would follow in Grandfather Bär’s footsteps and become a shohet, but I was not suited for it. I happened to be at the kosher butcher’s one day when a cow was brought in for slaughtering. Several men surrounded the pitiable animal. They tied its legs together and flipped the animal onto its back. They held the cow’s head firmly so that it could not move. Then the shohet wielded his razor-sharp knife with a single stroke. In a split second, blood spurted from the cow’s throat. After the animal was bled, the shohet examined the contents of its stomach and looked at the liver to determine if something the cow had eaten, such as a nail, might have rendered the meat unclean. If nothing in its entrails had defiled the cow, the butchering could begin. Tradition or no tradition, the bloody sight left me feeling sick.

The year of my Bar Mitzvah, Hanna, my beautiful 17-year-old sister, finished her secretarial training at the paper mill. She had black velvet eyes, and wavy ebony hair, along with intelligence, determination, and good work habits. Her employer asked her to stay on at the mill, to the great relief of my parents. Our financial crisis deepened as Father’s clients took longer and longer to pay off the credit my father patiently extended. The Jewish communities knew about our dire situation. They thought of Father whenever they needed a man for the Kaddish minyan and would be very generous in covering his travel expenses. If the funeral was in a large city, Father would spend all the money he received on leather skins, much to Mother’s disappointment.

❖❖❖

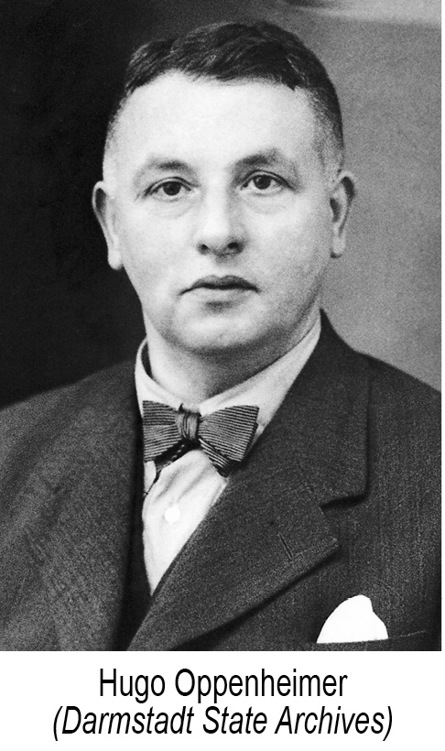

When I finished school in 1929, my parents decided to accept the Oppenheimers’ offer to give me a job in their store. Since I was determined to work hard and to be self-supporting, I bade farewell to my family and to my carefree childhood days. I was a penniless, 14-year-old country boy setting off for a free education and a new opportunity in the big town of Viernheim. The Oppenheimers would give me room and board in exchange for the housework I would do for Hugo and Julius” elderly mother. I would also have to take care of my own little room in the Oppenheimers’ attic. A whole room for myself! At home I only had a bed of my own.

I didn’t realize how difficult it would be for me to trade the Lauter Valley for Viernheim. Viernheim, with its 20,000 inhabitants, was only 25 kilometers away from home. But it might as well have been on a different continent.

Viernheim was situated in a wide open land where thriving asparagus and tobacco fields sprawled under an endless sky. For centuries the fertile flood plain of the Rhine River had nourished the soil and brought prosperity to the region. Without the protection of the mountains, the land lay exposed to the four winds. I felt vulnerable in the windy flatland.

Viernheim supplied laborers for the Mercedes-Benz plant and other factories in the nearby industrial cities of Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. Thus, the population was a mix of factory workers and farmers. In the center of town were the City Hall, the Catholic church, assorted small shops, and Gebrüder Oppenheimer, with its four display windows. The well-kept homes of the rich clustered tightly around the Catholic church. A little farther away was the business school and, a few blocks behind that, the synagogue.

Our work schedule started at dawn and finished long after the store closed. Early in the morning before opening time, I had to clean the store. New merchandise had to be unpacked and the shelves stocked. Then once a week, all four shop windows had to be washed, and I had to redo the window display using no money but all my ingenuity. All day long, all week long, I climbed up and down the ladder to get items for the customers, straightened the piles of goods, waited on Julius, Hugo, and their mother, and even worked on the cars. And there was still more to do. The Oppenheimers had out-of-town customers to whom I brought samples and deliveries. My employers trusted me to drive the Citroën, even though I was only 16. Despite the extra cushion on the seat, I could hardly see over the dashboard, and to other drivers and pedestrians, it looked as if the car had no driver. I would chuckle when people panicked, thinking they were seeing a runaway car.

Shop signs saying “German store”

are a true blessing...

Here [a German man] can be sure that

he has not given his

hard-earned savings to the

enemy of all that is German, the Jew...

A true German will shop only in German stores!

—“Viernheim People’s Daily,” December 10, 1934

Most of the townspeople received their pay on Saturday. So they would often ask us to come by on Sunday to pick up a small payment toward their bill. The Oppenheimers extended credit without charging interest, but a few customers even exploited that generous arrangement by not paying their bills at all. Bookkeeping kept us busy in the evenings and on Sundays. I took pride in my work, even in little jobs like winding up the smallest bits of string, flattening boxes, and folding wrapping paper. The two brothers ran an efficient and orderly business, and they appreciated my diligence.

❖❖❖

Life with the Oppenheimers also introduced me to an entirely different way of Jewish life. There was hardly any evidence in the Oppenheimer home that its occupants were Jewish. To my surprise their mother did not light the two Sabbath candles on Friday evening, nor did pictures of Moses or Aaron hang on the wall. They didn’t have two sets of dishes—one for meat and one for dairy. Back at home, when a kitchen knife belonging to the meat set came in contact with dairy products, Father buried the defiled blade in the ground for seven days to purify it. The Oppenheimers may have eaten kosher food at home, but when we drove through the Odenwald Mountains, we would sometimes eat in restaurants where the smell of smoked ham was unmistakable and the patrons dined on platters of meat drenched in milk gravy.

The Oppenheimer store even stayed open on the Sabbath. After all, Saturday was payday—the best day for business. Besides, like every other business in town, the store had to close for all the Catholic holidays. How could they also afford to close for Jewish holidays like Rosh-Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) as well? Of course, they observed Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). But what a difference from the way we had celebrated it at home!

At my boyhood home, on this most holy of days, my family would fast from evening to evening and attend the special synagogue services, including the Kol Nidrei, the haunting melodic prayer annulling any rash vows made during the past year. Before asking forgiveness from God, we would ask forgiveness from one another. My family made extensive preparations before Yom Kippur. Father took a chicken by its legs, its wings beating the air. He swung it over his head and mine (since I was the only male child) and spoke some Hebrew words. Then he turned the bird over for the ritual slaughter. Yom Kippur begins in the evening. We all took a complete bath, which was quite an ordeal because we had to heat the water on the stove. Only then would we attend synagogue.

A few days after Yom Kippur comes the festival of Succoth, or booths. We would sit together in a booth that Father had erected in our garden. There we prayed and took our meals. In the evenings we could see the stars through the leafy branches overlaying the top of the booth. Grapes and fruit adorned its walls, an expression of thanksgiving for the year’s harvest. The frail covering of the booth reminded us of the tents in which our ancestors dwelt in the Sinai desert.

At the Oppenheimers’ there were no booths, no thanksgiving prayers, only business. Succoth was seldom mentioned, and Hanukkah never. Unlike some Jewish families in Viernheim who burned candles at their windows, the Oppenheimers’ windows remained dark.

I had at least expected to take part in the cleansing ritual for Pesach, the Passover, packing and carrying away all the khometz kitchenware—dishes, forks, and spoons that had had any contact with leaven. When I lived with my family, I used to heat the stove until it glowed red and chase after the smallest crumb of leavened bread. Only then could we bring the special Pesach utensils into the kitchen to be used during the week of unleavened bread. But the Oppenheimers never ritually cleansed their kitchen.

I missed my family and the festive Pesach atmosphere, with the decorated table glowing in the light of the menorah. But even more, I missed the seder, the Passover meal. Each of us would be seated at the table with his own Hagadah, the special Passover prayer book. Being the youngest male, I would ask the Four Questions, starting with, “What makes this night different from all other nights?” Father chanted the story from the Hagadah, explaining the liberation from bondage in Egypt. Upon the table were the Haroseth symbols: grated apples with cinnamon, its brownish color representing the clay the Israelites used to make their bricks, and ground horseradish, which made us all shed tears.

Next to the table, Mother prepared the seder bed. She spread a fine linen cover over the couch and placed a silk pillow at the head. We wrapped up some matzoh and filled a glass with red wine, just in case the Messiah arrived and wanted to partake of the meal. We left the wine and matzoh out during the whole week of unleavened bread. Thereafter, the matzoh would end up behind the picture of Moses. As a little boy, I would reach behind the picture and secretly nibble on the Messiah’s meal.

Unlike my parents, the Oppenheimers gave no thought to the coming of the Messiah. Their empty Pesach consisted only of unleavened bread and a token appearance at the synagogue. Even at Pesach the business had first place. Hugo and Julius claimed that honesty and hard work were worth just as much as the observance of religious tradition. By their fairness, they helped people weather the economic depression—surely this was a mitzvah, a good deed. As time passed, I began to share their zeal for the business.

❖❖❖

In 1929 just when I started to attend business school, the economy showed some signs of revival. It proved to be an illusion. The tidal wave that started with the crash on Wall Street swept mercilessly over Germany, plunging people into desperation. Julius even complained that I had become too expensive for them. The unemployed lined up restlessly each day to get their work certificates stamped so that they would be counted as needy.

By the time I finished my three years of schooling, the air was tense with fear and frustration. I could see it in our customers. In the streets, marching hordes followed behind their party flags shouting slogans. The workers and unemployed together vented their anger. When factions clashed, it was wise to get out of the way. Riots flared up all over the land.

It seemed ironic to me to see the very same people who clashed in the streets come together on Catholic holidays. They walked behind a cross held aloft by the priest. Arrayed in ceremonial garments, he led the procession out of town and into the fields, where he bestowed his blessing. The sight of carved images evoked in me a deep-seated repugnance. The Torah stated clearly: “You must not make for yourselves a carved image.” Truly I dwelt in an alien land!

On Easter night Catholic youth would set fire to

a pile of wood on the church square, and

after receiving the priest’s blessing

and being sprinkled with holy water,

they proceeded to march up to Jewish properties

with burning torches, yelling: “The Jew is dead!”

—Recollections of Viernheim resident Alfred Kaufmann

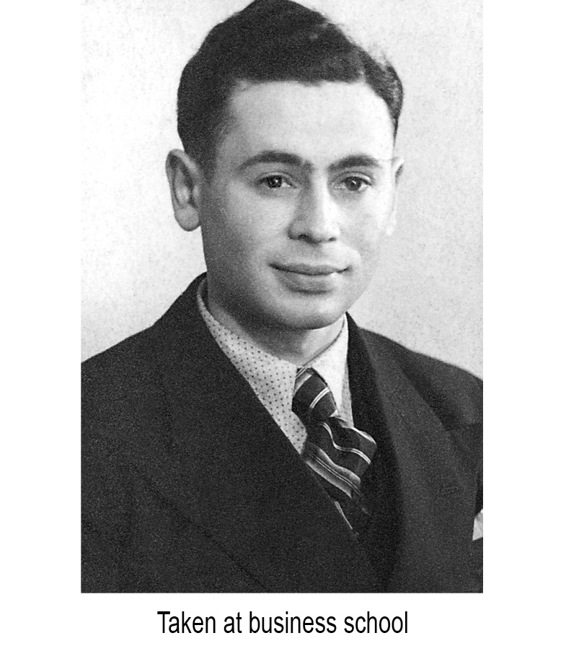

To my great surprise, when I graduated from business school, the Oppenheimers asked me to stay on as an employee—quite a respectable opportunity for a 17-year-old. It did not take long for the customers to ask to be served by “Mäx’che.”

Work hours never seemed to end; by evening I was worn out. I rarely had time for myself. I seldom managed to attend balls held by the Jewish community in Mannheim—not to mention the occasional ones in Viernheim, where more than 100 Jews lived. The non-Jewish dances on Saturday evenings were more convenient. They were my sole entertainment. Music inspired me, vibrating the fibers of my being, especially when I held in my arms a girl who knew how to waltz. I attended a few dances, even though most of the girls wouldn’t dance with me. I managed to find an exceptionally tolerant Christian girl, and she was a good dancer too. Ruth, a vivacious young lady, wasn’t ashamed to dance with a Jewish boy. I felt as if I were in heaven when we waltzed. But the music also made me melancholy. It brought back my dream of becoming a cantor like Grandpa Oppenheimer.

Julius and Hugo had no time for music, and I too had become completely absorbed in the business. The time came when the two bachelors would make a choice among potential brides. According to their criteria, the girls had to be Jewish and had to come with a solid dowry, which they thought necessary for a prosperous life. To me, the whole affair seemed more like negotiations over the purchase of a set of furniture than the choice of a companion for life. Hugo and Julius discussed the terms of the marriage agreement with their mother, who rendered her opinion. She lived just long enough to see her sons married—Julius to Frieda, and Hugo to Irma. Julius and Frieda’s firstborn, Doris, came along as a true consolation after the death of her grandmother. I became Doris’s favorite uncle.

2

The November day of our escape seemed endless. A heavy fog rose from the valley and intercepted the pale autumn sun. About seven or eight years old, Doris was too young to know that we had fled for our lives, but she sensed our anxiety and was restless and cranky. The dampness, the drafty cars, and the tension chilled us to the bone. I didn’t know why—perhaps it was a combination of anxiety and cold—but Julius and Hugo took turns getting out of the cars, stamping their feet in the cold like nervous horses. By nightfall we had another decision to make. It was impossible to stay overnight in the woods where we had parked—hunters might come around early in the morning. Besides, the cars wouldn’t protect us from the cold. This place in the forest had proved to be a good hiding place during daylight hours, but what now?

We decided to drive to an isolated inn situated in the remotest part of the Odenwald Mountains, a place where no one would know us. The fog dampened our headlights and the sound of the motors, making our trip through the mountains less conspicuous. The anxiety we felt in the forest intensified as we neared the place we hoped to stay overnight: Would this decision prove to be our undoing? We viewed ourselves as German. The Oppenheimers were wholly assimilated; only their surname identified them as being Jewish. My surname, Liebster, is German and means “most beloved.” Even in Viernheim the Oppenheimers had been discreet—not even a menorah in their apartment window to give them away. But now we felt in danger of betrayal. Our papers branded us “Israel” or “Sarah,” names forced upon us, and all Jews, by the Nazi officials.

That night at the inn, I was haunted by visions of the fearsome plague of Nazism spreading across the country. People had changed so suddenly. The lines between friend and enemy had blurred. I felt like the solitary prey stalked by a beast I neither knew nor understood.

❖❖❖

It was in January 1933 that President von Hindenburg had unexpectedly appointed a reichschancellor named Adolf Hitler. I was just 18 years old at the time, and I heard some of our customers denounce this event as a dangerous move. Soon, however, their voices fell silent. Nazi Brownshirts* rounded up political opponents, confiscating their papers and books and breaking up their meetings. Suddenly, there were no more rowdy marches and clashes in the streets. Public places were once again safe; children could return to playing outside. Now one party, the Nazi Party (the NSDAP),** controlled the country. Germany had become a police state, but the populace welcomed the new calm, which in the minds of many made up for the fact that some experienced a loss of liberty. In any case, people dared not express their innermost feelings. The threat of being hauled away as a dissident left most citizens numb with fear, ready to conform to the growing pressure.

* The Sturmabteilung (SA), also known as Brownshirts, were used by Hitler to gain political power through the use of street violence and the intimidation of political opponents.

** Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeitspartei, or National Socialist German Workers Party.

JUDA VERRECKE!

(Death to Judaism!)

—Nazi slogan painted on walls and windows

From the beginning of his political career, Hitler furiously denounced the “worst” enemies of the State—the Communists and the Jews. Hitler’s message was intensified by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. In his hysterical talks, Hitler promised employment, a Volkswagen, and better housing for the common people, the Volk. Factories had to come to a standstill while the workers listened to Hitler’s ranting lectures. Indeed, the Führer did provide jobs. Every morning all sorts of men cycled past our store with shovels tied to their bikes. Instead of standing in soup lines, they had work—maybe not the type they would have chosen, but at least they earned their bread. Hot or cold, fog or rain, they labored to level the ground along the Rhine River for the future autobahn, Germany’s first highway.

The Jew greedily stretched out his claw in order to pull the

German farmer into the abyss; that is when Adolf Hitler came

and stopped them—and Germany was released!

—German Farmers’ Special Day

The farmers fell in step with the new regime, and this helped the economy. The government moved to protect farmers’ property from lenders—if the farmers could prove that they were of pure “Aryan” stock. The masses hailed the quick economic recovery and seemed blind to the gradual strangulation of freedom. They hailed Hitler as their savior.

Adolf Hitler, you are our great Führer.

Thy name makes the enemy tremble.

Thy Third Reich comes,

Thy will alone is law upon the earth.

Let us hear daily thy voice

and order us by thy leadership,

for we will obey to the end and even with our lives.

We praise thee! Heil Hitler!

—School Prayer

We began to hear people make statements like, “Hitler wants order and decency. Germany should rally around its leader.” The Heil Hitler salute replaced the common greeting. It served as a constant reminder that Heil—salvation—comes through the Führer. It seemed that everyone went along, whether they wanted to or not. Who would dare refuse in public? Any possible voice of dissent had been terrorized into silence by the threat of “protective custody” in a concentration camp. I could see that our own customers voluntarily shut their ears to grim rumors of atrocities that were now beginning to circulate.

Viernheim stands loyally by Adolf Hitler and the Fatherland!

...Viernheim is Germany—and we are a great people—

in one beautiful national community!

Germany above us—and our Führer Adolf Hitler above all!

Hail Germany—Hail the Führer!

—“Viernheim People’s Daily,” March 30, 1936

The combination of guaranteed work, a low crime rate, and plenty of food acted like a sedative. Few raised a word of complaint against the degrading posters that depicted the Jews as an evil presence. Law after law hemmed in our freedom. The government organized boycotts against Jewish businesses. Julius and Hugo’s brother, Leo, had been forced to sell his candy distributorship for almost nothing to an “Aryan.” He then had to go to work in a factory. But because of their good relationship with their customers, Julius and Hugo felt safe, despite the fate of their brother, Leo.

It is an outright contradictory statement to say: “A decent

Jew,” since the expressions “decency” and “Jews” are