Полная версия:

Crucible of Terror

Dedication

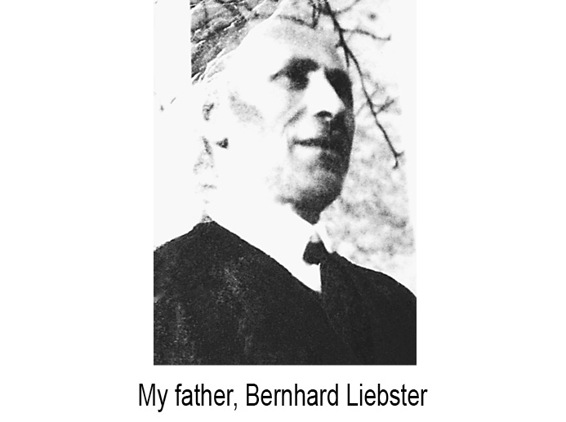

To my father Bernhard and my mother Babette

To Willi Johe

To Ernst Wauer

To Otto Becker and Kindiger, who risked their lives

to save me from a typhus epidemic in the Small Camp.

Foreword

For the first two decades of his life, Max Liebster knew the town of Auschwitz (Oswiecim) only as his father’s birthplace. Liebster grew up in an observant Jewish home in a small German town, but as a teenager, he was transplanted to urban life, where his bustling routine left him oblivious to the gathering Nazi storm clouds. In late 1938, the pogrom dubbed “Crystal Night” abruptly changed things; Liebster was suddenly overtaken by the rushing tide of hatred. Young Max embarked on a nightmarish sojourn that would eventually lead him back to the place of his father’s birth. In the camp at Auschwitz, Max became an eyewitness to the Nazi program of annihilation of the European Jews. Liebster survived, largely through a series of fortunate coincidences and help from unexpected quarters. Max Liebster’s vivid story describes the experiences of most German Jews— from initial disbelief over the virulence of Nazi antisemitism to the final agonies of the camps. Liebster’s language is not designed to present a gruesome account, but his description of his experiences in five camps does nevertheless convey the terrible reality he witnessed and survived.

While he was en route to Sachsenhausen, Liebster’s story departs dramatically from the familiar. By chance, he encounters an intriguing phenomenon—a group of prisoners known as the purple triangles. The purple triangle was borne by the Bibelforscher, or Jehovah’s Witnesses. They were prisoners of conscience, stubbornly committed to their principled nonviolence, and indomitable and brash in their condemnation of Hitler’s regime. In Neuengamme, Jews and Jehovah’s Witnesses are thrown together. Liebster gives us a close-up view of a victim group that seldom appears in the historiography of the Nazi era, a group that resisted Nazi indoctrination even in the concentration camps. Liebster becomes absorbed in the ideological battle he sees, for whereas the Nazis gave Jews no options for release, the Witnesses could gain their freedom, if they would just renounce their religious beliefs, something most Witnesses refused to do. Liebster, who later converted, was so profoundly affected by the purple triangles that he was moved to bear witness about their uncommon courage in the face of evil. This book is an expression of Liebster’s determination to bring their little-known history to light.

In recent years scholars have focused greater attention on the non-Jewish victims of the Nazi era. A few historians have begun to fill in the historical gaps regarding the Nazi persecution of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Max Liebster’s memoir adds an important, humanizing chapter to a story that deserves to be known.

Henry Friedlander,

Professor Emeritus of Judaic Studies

City University of New York

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the people and institutions who assisted me in various ways to put together my story as accurately as possible: Jürgen Hackenberger, Frau Scharf in the Reichenbach Archive, historian Hans Knapp, and the collections of the Darmstadt Municipal Archive and the Watchtower History Archive in Selters, Germany, provided historical material to confirm my memories.

Patrick Giusti provided invaluable technical help in handling the manuscript and correspondence. Monica Karlstroem translated newspaper clippings, song lyrics, and other items from the Nazi period. Charlie Miano’s artistic talents resulted in a wonderful oil portrait that captures my emotions so vividly. Tobiah Waldron kindly provided my book with an index. Rick and Carolynn Crandall accomplished the editing and typesetting work despite a tight deadline.

Walter Köbe, Wolfram Slupina, and James Pellechia first urged me four years ago to undertake this writing. It proved to be a mental and emotional challenge, but I am grateful for their encouragement. Jolene Chu, who has become our “adopted” daughter, patiently analyzed my statements and skillfully refined the text so that it faithfully expresses my recollections and feelings. And I am deeply grateful to my beloved wife, Simone, who has had the challenging task over the past four years of living my memories with me and helping me to put my story on paper. Her years of devotion and support have truly been one of the most precious blessings in my life.

1

Stay away from Jews-and soon

we’ll be rid of them, because

we don’t need any Jews in Viernheim.

“Viernheim People’s Daily,” 1936.

Viernheim, Germany; November 9, 1938. The damp, gray November day had barely begun. I watched as my cousin and employer, Julius Oppenheimer, wrapped his little daughter Doris in woolen blankets and carried her out of the house. He gently laid the sleepy girl next to her mother on the rear seat of the car. Frieda cradled her daughter’s head, full of curly locks, upon her shivering knees. Doris whimpered softly, her whimpers playing a duet with her mother’s sighs.

Julius’s brother Hugo and his young wife, Irma, climbed into the other car. Both vehicles had been hurriedly loaded with a few days’ supplies and important documents.

After one last look around, we shuttered the windows and locked the doors. Julius told me to take the wheel of his shiny Citroën. In solemn procession, I followed Hugo’s car out of the driveway and onto Luisenstrasse, turning right at Lorchstrasse. Around the corner in the dim light of the street lamp, one could barely make out the sign of Julius and Hugo’s store, Gebrüder Oppenheimer (Oppenheimer Brothers). Would we escape with our lives? Would the store and the Oppenheimer home escape harm?

The town of Viernheim receded behind us as we drove eastward toward the Odenwald Mountains. In the foothills, we passed the medieval city of Weinheim, lying in the midst of harvested grapevines. Soon we entered the barren forest. During the long drive, no one broke the silence. The serenity of the bare trees and the fresh odor of the damp earth did nothing to cut the tension. Our slow climb into the mountains belied our racing hearts—what would happen to us and to our business? Winding our way toward the misty summit, we took a secondary road that drew us farther into the forest, deeper into the gloom, and far away from any dwelling. There, far from any watching eyes, we brought our cars to a halt. For a long time we sat motionless, absorbing the deafening quiet that surrounded us.

❖❖❖

The decision to leave everything behind had not been an easy one. When the first reports about synagogues being burned had reached us, each of us believed that such vandalism could only happen in big cities, where the culprits could hide—never in our quiet Catholic town. After all, the Nazi-orchestrated boycott of Jewish businesses in 1933 had not touched the Oppenheimers in Viernheim. Their reputation for being fair with their customers had protected them. They sold linens and fabrics to many townspeople on credit, without charging interest. The villagers far off in the Odenwald Mountains knew that merchandise purchased at Oppenheimer Brothers would be delivered to them at no extra cost.

We felt more German than Jewish. Our neighbors were good, decent folk. We trusted that they would not fall prey to the Nazi thug mentality.

Get involved with a Jew

And you’ll always be cheated.

Enters the Jew and brings the devil with him!

—“Viernheim People’s Daily,” 1936

Our lives had been absorbed with making the business a success despite the hard economic times. For the past nine years, I had lived with the Oppenheimer family and had shared their joys and sorrows. During that time our hard work had paid off.

But now? Hysteria had overtaken all of Germany. Firestorms of hatred and violence toward the Jews had destroyed the memory of good deeds and burned bridges between neighbors. Nearby properties had already been set ablaze. Waves of hatred toward Jews had wrought terrible changes. Our trust in the benevolence of our neighbors had made us oblivious to the import of what was happening in the rest of Germany. But now we finally admitted to ourselves that we might be in danger.

Julius and Hugo decided we should leave while we still could. It wasn’t leaving behind material things that disturbed me the most. It was the foreboding feeling that things had changed forever for us, for all Jews.

❖❖❖

My mother was born an Oppenheimer. The archives in Reichenbach, a little town in the Lauter Valley of the Odenwald, first mention the name in 1747. A Jew bearing that name had to pay the special compulsory tax imposed on Jews. Eli Oppenheimer settled his family in the heart of this valley, tucked in the midst of the wild Odenwald Mountains in the German state of Hesse. He had chosen to leave the city for life in a primitive village.

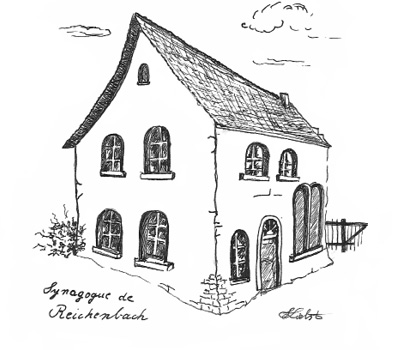

If he had come seeking security for himself and his family, he certainly found it. By 1850, ten families bearing the name Oppenheimer lived in Reichenbach. That gave them the number of males needed for a minyan, a Jewish prayer service. A small synagogue arose next to a little stream. The entire Jewish community could come to celebrate Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, and perform the ritual throwing of a stone into the water while asking Adonai to drown their sins. Another Oppenheimer, my grandfather, Bär, presided over Reichenbach’s chorus for years until his death. He also served as cantor and as the shohet (a Jewish butcher who slaughters and bleeds animals in accord with the tradition—using a sharp knife and a quick stroke).

Bär lived in a tiny home not far from the synagogue. He doted on his children—Adolf, Bertha (nicknamed Babette), and Settchen. Ernest Oppenheimer, a cousin of Bär’s, had emigrated to South Africa and went on to become a diamond magnate—he became Sir Ernest Oppenheimer when he was knighted in 1921. But Bär’s life of simple poverty left him neither bitter nor jealous. He delighted in friendly exchanges with all whom he met, and his warmth and vitality lived on in the minds of the villagers long after he died. When I was a boy, people would say to me, “You truly are Bär’s grandson,” and I glowed at the compliment.

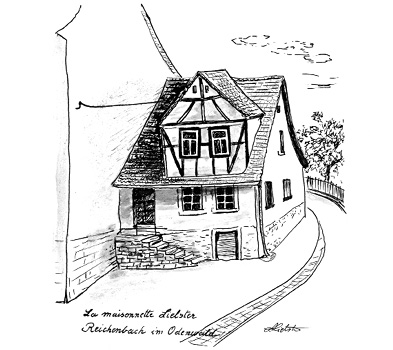

When the time came for his daughter Babette to marry, Bär Oppenheimer received offers from the larger Jewish community in Frankfurt, where there were many more eligible bachelors. Bernhard Liebster would become Bär’s new son-in-law. The devout young Jew had been born in Oswiecim (also known by the soon-to-be-notorious German name Auschwitz), which was then part of Austria. Bernhard left the big city and his homeland of Austria to move into the shohet’s humble home in Reichenbach, Germany. He married Babette and even agreed to take care of Settchen, Babette’s invalid sister. In the cramped house, he found a place to set up his cobbler’s workshop. In 1908, Ida was born, followed three years later by my sister Johanna, whom we called by her nickname Hanna. Father wasn’t home to witness my birth in February 1915. He was at the Russian front, fulfilling his patriotic duties and defending his adopted fatherland.

In Father’s absence, Mother had to bear the load of caring for three children, as well as her frail sister. My sister Ida had to look after me. I remember that she once struggled to get me to come home. As a boy of three, I stood at the school railing, gazing at an unexpected herd that filled the school yard. So many horses! My curly, black hair and their silky manes blew as the wind carried the mingled odors of straw and horses. The World War had ended. Disillusioned, worn-out soldiers on their tired mounts returned home from east and west. Soon, for the first time, father and son would meet.

Ida took her oversight of me very seriously. One day she obtained special permission for us to go to our neighbor’s home. She had to remain in the Schack’s doorway while I went inside, where only males were allowed. An eight-day-old baby boy lay upon an embroidered cushion on top of a lace-covered table. Little boys stood around the table holding candles. I was given one too. The mohel stepped up to perform the circumcision. As soon as the baby cried out, my candle began to tremble, catching the tablecloth on fire. I collapsed to the floor. The baby’s wails and the sight of blood had got the best of me—and not for the last time!

Father struggled long and hard to raise us out of dire poverty. He was a first-class cobbler, but with unemployment and inflation getting worse by the day, nobody had money for new shoes. He repaired ladies’ shoes, farmers’ boots, and stonemasons’ clogs. He saved the leather from old shoes to mend others again and again. But as time went on, fewer and fewer people were able to pay. Mother would get upset. She was the one who had to make ends meet. She noted our grocery bills in a debit book kept by our neighbor Mr. Heldmann, the kind and trusting grocer. As soon as money came in, Mum went over to the Kolonialwarengeschäft, a shop with all sorts of foods, to settle our debts. She grumbled constantly over our family’s empty cash box.

During the deepening economic crisis, we in the rural areas could live off the land. We had a vegetable garden behind the house and a little potato field down by the plum and apple orchard. Dried apples and potatoes would carry us through the winter. During crisp autumn evenings, Dad would sit at the table after supper, peeling and slicing apples. We kids hovered nearby for samples.

Mum never stopped working. She couldn’t—she had her hands full with our family of six. And her sister Settchen required extra care. Mum did all the wash by hand, using ashes instead of soap. During the summer she did the laundry outside. In the winter she washed our clothes in the kitchen, where she heated water on our little wood-burning stove. On rainy days she did the mending, somehow keeping our threadbare clothes together by patching the patches.

When the sun came out, Mum would work in the garden. She pulled weeds, sowed seeds, and cultivated the well-kept rows of vegetables. Our little plum orchard yielded baskets of ripe fruit. Mum removed the pits and brought the fruit to our neighbor’s house, where there was a large built-in basin in the cellar for making jam. Mum had to stir and stir and stir to keep the mixture from burning. The exquisite aroma of her frothy jam swirled up from the simmering copper vat and wafted across the street to the school yard, summoning me home during recess for a slice of bread and sweet foam. The jars of jam would last us the entire year.

Day after day Mum hovered over the hot stove. Our meals, though very simple, were delicious. She would buy grease from the kosher butcher with which to make gravy, the sole embellishment for our dinner of potatoes. And how she worked to keep the dairy utensils separate from the meat ones! Faithfulness to Jewish tradition meant that the two sets were stored in two different cabinets and had to be washed separately as well. No wonder I hardly ever saw Mother sit down!

Sometimes when Aunt Settchen was not lying under a heavy down-filled comforter, she would sit in her armchair wrapped in layers of blankets. Only her dark, cavernous eyes showed. Or she would stretch out her long, bony fingers, asking for a cup of herb tea to help her digestion. She anxiously awaited her small pension. On the 10th of each month, she would say, “In five days it will be the 15th; half of the month is gone. Then, only two more weeks until my payment comes!” She would sit and look out the window next to her chair. Her dark eyes would suddenly light up when she spotted Julius and Hugo, her cousins, coming up the street. They never failed to stop by when they did business in the nearby villages and farms. They always had kind words, smiles, and a little cash for Aunt Settchen.

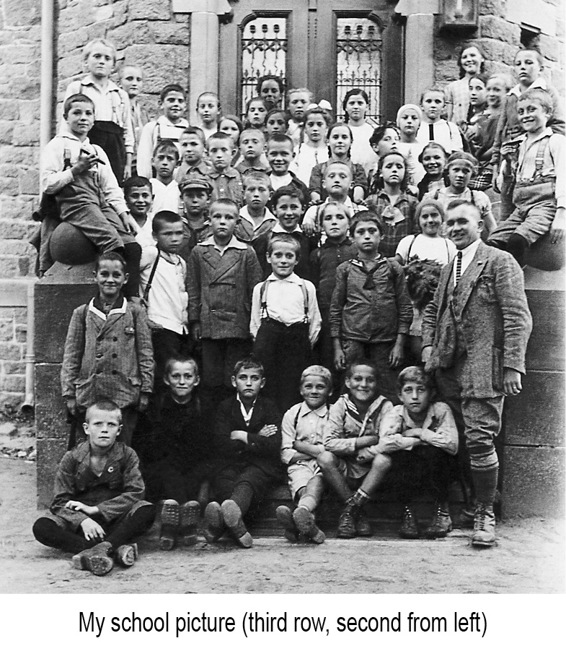

Ida hated school, but she wasn’t afraid of hard work. In 1924, at age 16, Ida finished school and looked for a job as a housekeeper. She wanted her independence as soon as possible. I was nearly ten years old by then and glad to be out from under her diligent mothering. We never played together anymore. I had my own friends. Together with the boys, I slid on my feet along snowy Binn Street or down the frozen Lauter River, ran about green meadows, shuffled through drifts of crisp leaves, watched the neighbors’ goats, and played with a boomerang. A brief moment of inattention and I was marked for life when the boomerang swung around and hit me square on the chin.

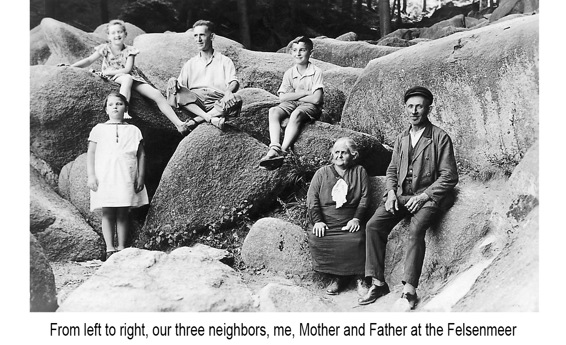

The Felsenmeer—the sea of stones—was my favorite playground. Sometimes my family would take our Sabbath walk here. It was right at our doorstep and within the limit of a Sabbath day’s journey.

Cascades of sleek boulders seemed to tumble down from the Feldberg summit, which culminated at 514 meters and ended in the meadow. Legend has it that a giant living in the Hohenstein Mountain had a serious quarrel with the Feldberg giant. The Hohenstein giant hurled the mammoth stones across the valley. The Feldberg giant was buried by the stones and imprisoned in a terrifying abyss. Climbers who stepped too heavily on those rocks might hear him roar!

As my friends and I ran down the path alongside the Felsenmeer, our boyish laughter echoed loud and clear throughout the majestic forest. If we stood quietly, we thought we could hear grumbling noises from under the rocks. Sometimes we glimpsed the giant’s eye, twinkling blue or dark gray, depending on the color of the sky. The eye peered out from the bottom of the stony river, which gave us crystal-clear water to quench our thirst. We cooled our red faces and splashed one another. The spring is still called Friedrichsbrunen, named after a German legend of ancient times.

The haunting legacy of the gray granite boulders had spooked people since time immemorial. During heathen times, on nights of the full moon, cloaked figures at secret meetings pronounced terrifying spells and sacred vows, summoning spirits to rise up from the abyss. But for my friends and me, the forest with its bewitching stony river held no secrets anymore. We jumped from one monster to another, competing to be the first to reach the Riesensäule. This giant column, a fallen pillar, was more than nine meters long and four meters around. Hewn from a single piece of bluish granite, the masterpiece had been erected about 250 C.E. by the Romans. It had a 60-centimeter-high niche to house an idol. The Riesensäule pillar survived the Roman departure and continued to be used as a holy site by an ancient Germanic tribe that held sacred dances around the stone in springtime. It later became a Christian shrine devoted to Saint Boniface. The sacred fertility dances continued for more than ten centuries, alongside Catholic rites. In the middle of the 17th century, a Catholic priest by the name of Theodore Fuchs converted to Protestantism. He established himself as a minister in Reichenbach (1630–1645) and pronounced a prohibition on the heathen dances. When his proclamation proved to be of no avail, he took the drastic measure of toppling the pillar.

As children, we were far removed from the worries of the postwar generation. We heard adults speak often about the World War and the hated French occupation of the Ruhr, the land of iron mines. Or they talked of inflation, lamenting the ever-rising price of groceries and the diminishing value of the mark. What cost 40 marks to buy in 1920 when I was five, cost 77 marks a year later, and 493 marks a year after that. As bad as those increases were—prices doubling and tripling each year—in 1923 inflation went wild. In January of 1923, that same 40-mark item would have cost 17,972 marks; by July, 353,412 marks; by August, 4,620,455 marks; by September, nearly 99 million marks; by October, 25 billion marks; and by November, more than 4 trillion marks. People needed a wheelbarrow full of money—21 billion marks—to buy one loaf of bread! I only knew that Father gave me 10,000-mark notes to play with.

The grown-ups often discussed politics—Socialists, Communists, Worker Party, Zentrum Party—all words with no meaning to us young ones. One thing we did know: People were out of work, including some of our fathers and older brothers. Some, it was said, had to stand in long soup lines. There were rumors of unrest in the cities.

Things were no better in the Lauter Valley. The two small factories, a paper mill and a manufacturer of prussic acid, had only a handful of orders to fill. Even the main industry of the valley—stonecutting—had dropped off considerably. There was little demand for cut and polished red, gray, or blue granite for monuments, buildings, and gravestones. For the young children of the common people, the prospect of work was nonexistent.

My mother’s cousins Julius and Hugo proposed to my parents that when I finished school, I could stay with them and their elderly mother in Viernheim. They could use my help in the Oppenheimer Brothers store. They would also send me to a business school nearby to receive training as a salesman. This offer provided some peace of mind for my family.

❖❖❖

By now, Ida worked as a maid, and Hanna, my quiet and studious sister, was being trained as a secretary at the paper mill.

As for me, I was about to become a man—the time had arrived for my Bar Mitzvah. In preparation for the big event, I went to the town of Bensheim every Sunday. Our rabbi lived here, at the entrance of the Lauter Valley. On foot or by bicycle, I savored the seven-kilometer trip through lush meadows. I was the only candidate from the valley preparing for the Bar Mitzvah reading of the Torah. The rabbi, an open-minded and respected man of great patience, helped me with the pronunciation of the text. I struggled with the strange Hebrew characters, and it was even harder to remember what they stood for. Understanding is not the important thing, I was told, but rather the exact pronunciation of the Hebrew text in the sacred language of God. By the time I was 13, my reading was going smoothly. I eagerly awaited the day when my boyhood would end and I would be counted as a man. Then I could be included in a minyan, a group of ten adult male Jews, who had to be present to hold a public Jewish prayer service, such as Kaddish, a special prayer that the bereaved recite for the dead.

The big day arrived. I felt nervous and excited at the same time. The rabbi came to our little synagogue. He gave a heartfelt welcome, stepped down from the platform, and sat among the men in the audience. My mother and sisters sat in the balcony, the place for the women. My heart pounded as I climbed the two steps and opened the little door of the engraved wooden barrier separating the Jewish congregation from the platform. Here in this special place, the holy writings were usually kept in a sculpted wooden closet, hidden from the view of the audience by a burgundy curtain. Awaiting me on a pulpit in the middle of the stage lay the Torah scroll, unrolled to reveal the portion of Scripture I would read. The holy scroll was bathed in the light of a candelabra with seven branches.