Полная версия:

The King is Dead

John Brice had ventured to Babylon with his faithful genius about him; and if that was where he wanted to be, what was hers to add? He didn’t love her, she thought. He didn’t mean it; either he was living in a dream or he was lying. So sooner or later he would have grown tired of her and he would have started to hate her, and she’d be alone and not so young anymore, and stranded in New York City.

The door opened and a woman came in, and without breaking her gaze through the window, Nicole said, May I help you?

Darling, it looks like you could use a little help yourself, said Emily. I was going to invite you to lunch, on me.

Nicole blinked in surprise. I just ate, she said.

You look like something just ate you.

I got a letter, you know—she gestured—from John in New York.

He still trying to get you to come up there with him?

Nicole shook her head. No, she said. He’s gone.

Then forget about him, said Emily. You’re twenty years old. There’ll be another, believe me. There’ll be another.

But Nicole wasn’t sure there’d be another at all. What if he was the only one, ever? For a few days she thought about writing him back, but she couldn’t have told him anything; it was a madness that started anew each evening, a paralysis in her blood that prevented her from sending so much as a note to him. It was too much for her: the weeks of wandering around with a blank look on her face, an entire symposium she conducted all by herself. Answers, another idea, another question. She never did decide what to say to him, where to start, what good any of it would do, so she never wrote back to him at all.

11

One morning in early March, Mrs. Murphy with the red hair and white gloves came gliding into Clarkson’s, accompanying her fourteen-year-old daughter for her first brassiere, in preparation for her journey to the city’s most exclusive finishing school. She got to chatting with Nicole while the girl was in the dressing room. Now, love, a woman like you can’t spend the rest of her life working in a place like this, said Mrs. Murphy. Mr. Murphy’s cousin works for a radio station in Memphis, and he was just telling us how they were looking for a girl to work there, someone to help around the office. Maybe you should call him, Howard Murphy. He’s in the directory.—Oh, look, and here’s my baby all dressed up like a woman. Lift it up a little, honey. In front. In front, just a little. The girl watched as her mother slipped her thumbs under the top edge of her own cups and tugged them gently upward. The girl did the same.—There you go. Mrs. Murphy turned back to Nicole and unsnapped her little black clutch. We’ll take three, she said with a small smile, and drew out a carefully folded bill with her fingertips.

Thus Nicole took herself to Memphis. She called Howard Murphy: The radio station was looking for a Gal Friday, they were hiring—yes, right away, if she was qualified; she mailed a letter detailing her skills and received a phone call two days later; she took a train out for an interview and returned to Charleston to find the job offer waiting for her; she made up her mind, she accepted, and she made plans; she packed a trunk with dresses and effects, and she moved, walking through the door of her new house—a tiny little furnished place a woman at the station had found for her—only six days after Mrs. Murphy had stopped into the store.

There was so much to do, and so much that was different: the wider accent and stronger sibilants, the lights on Beale Street, the new fortune of a new city. Now she and John were two giant steps apart and facing farther away. Maybe a seam in her mind had come undone, all of her love had spilled out into Memphis, and Memphis didn’t care at all, and swept it away. But there was this: the strangest thing. She began to miss John’s car terribly, it was a helpless assignment of her affections, and she wrote in her diary that if she were to sit in it again she would fill it with tears. Then she tried to put it out of her mind; but every so often, and for a few years afterward, she would turn her head whenever a car of a similar blue went by on the street, knowing it wouldn’t be John, knowing it wouldn’t be a happy day even if it was. Still she turned her head, because she was looking for herself at twenty.

12 STAY

Walter Selby’s throat was stopped with visions; sex trickled down it like whiskey, the blood behind his eyes was doped a desperate shade of blue, and nonsense verse rang in his ears, a singsong of refraction and perfection. When the car pulled away that night, with Nicole in it, the neighborhood was quiet and he was dazed; already she was not just gone but missing. He went into his house, took his jacket off, and walked to the bathroom to wash his face, pausing before his reflection and rubbing his cheeks with his hand so that his features distorted. Then he shook his head, took one last look at himself, and walked into the living room, where he lowered himself slowly onto his couch. Over and over he went up to touch the night’s events; again and again he retreated, as if he were unsure that they were real. He opened the telephone directory and looked her up: and there she was, a plain entry in the order of names—and there was her address, a road he recognized. He gazed at it briefly and then closed the book and carefully put it back beneath the base of the phone, as if this small gesture of control would be sufficient to prove that he wasn’t such a fool after all, he hadn’t lost his dignity and he wasn’t a boy.

He didn’t sleep well that night; he didn’t work well the next day. He arrived at his office dead tired and distracted and paused in the dark cool hallway before the door pane of frosted glass. Behind that door, and every door on the floor, and every floor in every building, there were men and women conducting the business of the day.

Q: What were they making?

A: Everything but love.

He entered and his secretary looked up with a slight grimace. The Governor’s called three times already, she said.

He’s still in Nashville, isn’t he? said Walter, worrying for a moment that the man might be holed up in his suite downtown, on some surprise visit to his western constituents.

He’s in Nashville, all right, the secretary said. He’s upset about something.—The phone rang, she answered, Yes sir, she said. He just walked in.

Walter Selby nodded, went into his office, and picked up the receiver. Selby, the Governor said. He made no introduction, he needed none: his voice—soft, insistent, and musical—could not be mistaken. Where were you last night, my friend? I tried to call you about a half dozen times. There’s a senator from Knoxville who wants forty thousand dollars attached to the Parks bill for some war memorial, and we don’t have it. He’s threatening to make a big deal about it, and it’s going to make us look like we don’t care about the war dead. Forty thousand dollars. Of course, it’s his brother-in-law who’s going to build it, but who’s going to listen to me on that? War dead…. War dead…. Forty thousand isn’t a lot, but we don’t have it. We don’t have the money: we just don’t have it. And you’re off at a ball game….

The Governor knew everything, that was given; the Governor was a magic priest of populism, a genius at the whip, and Walter hardly noticed the trespass. Instead, he found himself trying to remember what he had just heard, the words and the Governor’s exact intonation, so he could relate it to Nicole when he saw her again. The Governor had become a portrait of the Governor, and all its colors were richer than real. Are you listening to me? said the portrait, its voice heavy with political emotion.

Of course, said Walter. This is Anderson we’re talking about.

This is Anderson, said the Governor. I need you to get him to back down. I need your voice: you talk to him. Appeal to him. If that doesn’t work, think about what we’ve got that he wants more than he wants a war memorial, and then tell him you’re going to take it away from him.—And without so much as a good-bye, the Governor hung up the phone.

13

Now, Senator Anderson, the Governor has asked me to call you and talk to you about this war memorial. The budget’s tight as can be …

I know it is, said Anderson. But, goddamn, I’ve got over two score dead boys from this district, three or four of them from the most prominent families in the state and all of them good supportive people.—Supportive of the Governor, too. They’ve given up their sons, and they’ve been waiting almost a decade for some sort of official recognition. You, of all people, should understand.

Yes, said Walter. I understand. I honestly do. And you can have the money. You can have it.

This gave the Senator pause. I can have it? he said, a little more quietly.

Sure you can, said Walter. All we have to do is find something else in the budget to take out.

Something else? said the Senator.

Yes. So I’ve been going through it again.

I’ll bet you have, said the Senator. What are you trying to tell me?

Well, here it is. It’s not your district, but Strachey right next door’s got about fifty thousand tied up in this little tree-planting business. He wants to prettify the highway from Crossville to Cookeville. Walter slipped his hand under the waistband of his underwear and gently, thoughtlessly, cupped his scrotum.

… That’s his wife’s project, said Anderson softly. There was an old silence on the line. The Senator had held his office since the days when his district was lit with kerosene, and was reelected at the end of every term on a platform of sentimentality. He had never been much of a statesman, and he was growing tired.

In time Walter spoke. Is that right? he said.

You know damn well it is. You know if you try to kill his wife’s beautification program, he’s going to come after you.

That’s all I could find. We can handle him.

God Almighty, said Anderson. He’s going to come after me, if you tell him why. I need him for the new maternity wing on the hospital. The man thinks, because he was born in his mother’s bed, that’s good enough for everyone.

Anderson was starting to drift. Walter Selby was nodding silently and absently drawing a poplar tree on a sheet of official stationery. That’s all we’ve got, he said. What do you want me to do?

You tell the Governor … Ah.—Anderson sounded close to tears. You tell the Governor I handed him this county on a silver platter.

He knows, said Walter Selby, but I’ll tell him again. The budget was safe now, and he could afford to humor the man. How’s your own wife doing? Still got a thousand recipes for rhubarb?

Yes, said Anderson, but all the life was out of him now. She’s published them in a book.

That’s fine, that’s great. I’ll have to go find a copy, and you give her my best.

I will…. Well, I guess I better go now, said Anderson. He was sixty-eight years old, and his only son had passed the last thirty years drooling his supper down his chin in the Nashville Home for the Mentally Impaired.

Go on. I’ll talk to you tomorrow, said Walter Selby.

There were some reports in a stack on the corner of his desk; he glanced at them and then turned his chair around so he could look out the window. The morning sun was crooking through the branches of the tree outside; overhead, a pair of perfectly formed cloud puffs were gliding across the dark-blue sky. Life was short and singular and the State was on his desk, the day was bright and angled toward the evening, and Nicole was the name of happiness. He nodded softly to himself and then turned back to the day’s work.

14

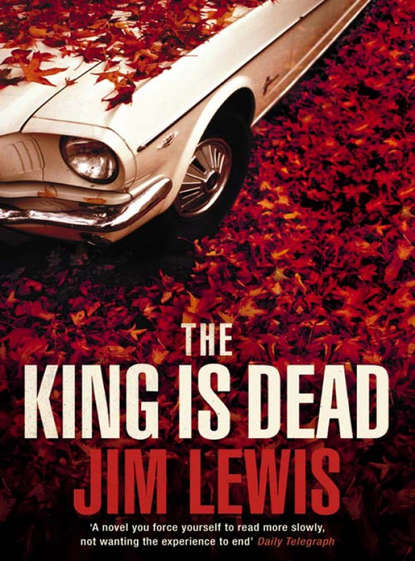

He waited that night until nine, and then he found her name in the phone book again, took the telephone receiver from its base and quickly dialed the number, already beginning to pace the floor before the rotary had returned to its resting place from the last digit. There was a pause, within which he could have planted an oak tree. Then the line began to ring,—rang again,—and rang seven times before he reluctantly hung up. Having made the effort, he found it almost unacceptable that it should have no effect, and for several minutes afterward he was unable to sit down; instead, he walked the length of his living room and then returned to the telephone and dialed her number again, with the same result. He was needled and stung, now. A police car passed outside his window, siren whooping into the darkness—not a common occurrence in that neighborhood—but by the time he got to his front porch it was gone. There in the driveway sat his car, big-shouldered and black. He considered driving over to her house. And what would he do there? Wait outside. In anticipation of what? He couldn’t say, he wouldn’t have been brazen enough to try to approach her whenever she finally came home. Where was she? There was nothing for a man to be, but lonely.

At last he went to bed, if only to close his eyes. Through the sleepless hours he saw her telephone number, he saw her friends, he saw the car they had ridden in. He saw everything but her face; she was so beautiful that her features had disappeared, as if in a blindness begotten by the brightness of her smile. He spoke out loud. You are a fool, he said. Go to sleep. And he went to sleep.

15

Late the following afternoon the Governor called. I’m coming in on Thursday, he said. We’ve got a brand-new firehouse opening up down in Smollet, and they asked me to come cut the ribbon.—There was great enthusiasm in his voice: the Governor liked openings of every sort, schools, hospitals, TVA projects, all things municipal and structural. He would drive two hundred miles through rain and fog to sit for an hour on a podium in some county seat and speak for five minutes on the occasion of the opening of a new Hall of Records, be it little more than a spare room in a courthouse. Write me something, will you? the Governor commanded. Get in a few lines about the utilities program we’ve been pushing here, but don’t make it look like Nashville’s trying to cram anything down their gullets. Just remind them, somehow, that we’re well aware that it’s our state, our resources. You know how sensitive those people can be.

How long do you want to go? said Walter.

Not very, said the Governor. We can save the big show for some other time.

Walter made an assenting sound, and there was a silence; then the Governor took an audible breath: exhaustion, concentration, or just air.

… What else? said the Governor.

What else?

What else do you have for me? Anything?

Nothing big, said Walter.

Well, tell me something small then.

For a second Walter considered mentioning Nicole. If the Governor didn’t already know, he’d want to be told, and he’d like the story; he’d have a little file on her in a day. No. He spoke up. There was an accident out in Farragut, a school bus went off the road and down into a gully.

Ah, that’s terrible, said the Governor sorrowfully. How bad is it?

So far, not too bad, said Walter. A couple of high school kids with broken bones.

That’s bad enough. We’ve got roads in this state that haven’t been repaired since Davy Crockett was in the legislature. Have the papers gotten hold of it yet?

Some local editions, round about where it happened.

Ah, shit. Get me the name of an editor out there. I’m not going to say anything, but I want to know who I’m not saying it to.

The editor’s name was McAllen, then Walter sat down to write a few remarks for the Governor to speak in Smollet. History, promise, revenue. He considered calling Nicole when he was done, but anybody could have interrupted him—his secretary with some papers, the Governor on the line, officials and lobbyists, and others and others.

16

It was four days further before he reached her; at last one evening she answered, and when she did he was so surprised that he didn’t know what to say. There was a bar of silence. May I speak to Nicole Lattimore, please? he asked. This is she, said Nicole, her voice giving nothing away, not surprise, delight, or suspicion. It was a certain reserve that she’d learned since she came to Memphis, no more than a polite and professional way to answer the telephone.

He reached up and touched the knot of his tie with his fingertips, to make sure it was straight. This is Walter Selby, he said softly. We met the other night, I guess it was about a week ago, at the ball game, in the parking lot afterward. I hope you don’t mind my calling.

Not at all, said Nicole, who just moments earlier had been measuring the century for solitude. She put her fingertips down on the edge of the table before her and listened while he made his way through an invitation, a date, dinner. The simple fact of his attention was gratifying to her, and so was his obvious nervousness. She hadn’t had much in the way of romance since she came to town; the boys in the car had been friends, that’s all; one of them worked in the advertising department at the station, the rest were his pals, and after a bit of jockeying they had settled for adopting her as a sort of mascot. It was just as well: she’d needed a few weeks to set up her little house, a few more to acclimate herself to her new job. The radio station was big and busy, and they needed her everywhere, all the time, answering phones, fending off salesmen, fetching reels of tape, cataloging 45s.

But Walter Selby was an important man, wasn’t he, and he was asking to take her out to dinner. She felt, for the first time in a very long time, an advantage on the world. She wasn’t frightened of him. She agreed to dinner; she saw just how it would go, on that night and the nights to come. They would talk, maybe they would laugh; they would date a little bit, now and again; perhaps she would touch his bare chest with her hand and burn away a little misery; and then one way or another it would end, and she would be six months older.

Later that week he came to her door in his Custom, carrying flowers and wearing a dry smile. He’d spent fifteen minutes at the florist’s, but now, as he rang the bell and waited, the flowers looked strange to him, like glass, and he could hardly remember what they were called or see their colors. Blue, light blue, red, bled. Nicole came to the door and he bore down for an instant, taking in her smile and scent and skin. She greeted him warmly and invited him in while she found a vase, but he came no more than a few feet over the threshold; the house was so small, he barely fit into it. She kept talking to him as she walked back to the kitchen: This is terribly sweet of you. I haven’t had flowers in here since I moved in. I know I have a vase, somewhere, I’ll have to rinse it out. You don’t mind waiting, I hope.—She trimmed an errant leaf off one of the stems. There, she said, and turned around to find him nowhere. She laughed and called, Walter?

I’m here, he said from the other room.

All right, make yourself comfortable, said Nicole. I’ll be with you in a moment. And thank you for these, they’re beautiful.—She could hear nothing from the next room, and she imagined him standing politely, just inside the door, patient, still, and willing to wait.

He took her out and took care of her. She didn’t have to think about anything except how to be winning and pretty, and that she could do. At the table he spoke some, playing with the cuff of his white shirt. He gave up a little bit of family history, a word or two about his time in the service, and how he’d come to Memphis afterward.

She was judging him gently as he spoke. He knew things and had a thousand secrets to tell or not to tell. His hands were clean and strong: they had been purified by war, whatever war had been. He was older, and he was lovely, in his way. Do you like him, your Governor? she asked.

She’d expected a simple affirmative, but Walter Selby paused a little, as if the question was entirely new to him; and he smiled to himself, thinking about words of praise and what they were worth. Like would be misleading, he said at last. No one likes anyone when anyone is governing. But he’s a brilliant man. His job is to make the state prosper, and he does well on that account.—Walter looked around the dining room and then leaned in, and Nicole leaned in to listen. But I’ll tell you how he does it, he said softly. Not too many people know this. Every night our Governor goes down into a dark room in his basement, lights a black candle, swishes some whiskey around in an ivory bowl, and waits for the Devil to come whisper in his ear. And the Devil tells him everything he needs to know for the next day.—He wagged his finger. Now, that’s a secret. That’s how it’s done.

He sat back and smiled, and Nicole smiled too, but more thinly. You’re joking, she said.

He’s a complicated man, said Walter.

She lowered her eyes and let her mouth go soft from relief. I suppose he would have to be, she said. The question is, what does the Devil want in return?

Oh, said Walter, Old Scratch won’t ever go wanting for a pleasure ground, as long as he’s got the State of Tennessee.

You’re a cynic, said Nicole.

I’m hopelessly in love with a slovenly queen, but she scorns my affections; when I try to dress her in suitable robes or better set her table she turns her haughty back. Sometimes I sulk to cover my shame. Then morning comes and I try her again.

That’s sweet, said Nicole, and she smiled as if she’d swallowed the sun.

The conversation wandered from there: back to his time on the campaign, forward to Memphis, back to Charleston and her schoolgirl days, her parents, Emily left behind. In the minutes the table vanished, the restaurant dissolved, the city pitched away all its pettiness. He asked her about the radio station; he’d met the owner once during the Governor’s campaign. Oh, it’s very interesting, really, she said. I don’t quite understand it all yet. I don’t know much about music, except for the Hit Parade; but something’s going on that’s got all the fellows at the station excited, and you wouldn’t believe the sorts of people who come through.

What are they like?

Wild men, she said, laughing. Just wild men. They come up out of the swamps, they come down from the trees, and they never say anything but they yell it at the top of their lungs. She leaned back in her chair and crossed her legs. My job is to be very nice and friendly and try to make sure they don’t burn the place down. She reached for her wineglass, and a small silver bracelet slipped out from under the cuff of her sweater and glittered in the candlelight as it dangled from her white wrist. It’s like they’re fighting a war.—She grimaced.—I’m sorry. That must sound to you like a very silly thing to say.

No, said Walter.

You being a hero and all that, she said, and thought of the word’s possible meanings for the first time when she said it.

He frowned, on familiar ground. They gave me a medal. They could have given it to anyone.

That’s not true, I’m sure, said Nicole, though she wasn’t. You were in the Pacific?

He didn’t want to talk; he wanted to watch her, but she had turned the table back to him, and he felt obliged to take it. The Philippines, he said. Some of the South Sea Islands.

What was it like?

He lowered his eyes. What to tell? The islands were beautiful, he said. Everything was huge and green. I was very young.

Nicole nodded solemnly, because the hour had suddenly become solemn. She had intended no such seriousness, and neither had he; but there it was. Eddy was very impressed with you.

I hardly remember what I did, he said. It was a good long time spent bored and waiting, and a few short moments of absolute terror. When it was over, I didn’t know where I’d been or who I’d hurt. She nodded again and swallowed a question, one she often wanted to ask afterward, always with the same terrible curiosity, a sickening lurch made more shameful for the fact that she felt like she was seeking it. Who did you kill, Walter?