Полная версия:

The King is Dead

Things about him that she never could be comfortable with: He spoke to her as if he were trying to coax her over a cliff. He judged the world immediately around him severely and without sympathy. He was moody. He had no other friends but her. Many things had come easily for him—money, for example, and self-confidence, and a sense of purpose—and he didn’t understand that those things didn’t come for her at all. He could be stubborn and impatient. He was more sure of his feelings for her than he should have been, and there was no reason why he might not change his mind. He was a field in which disappointment grew.

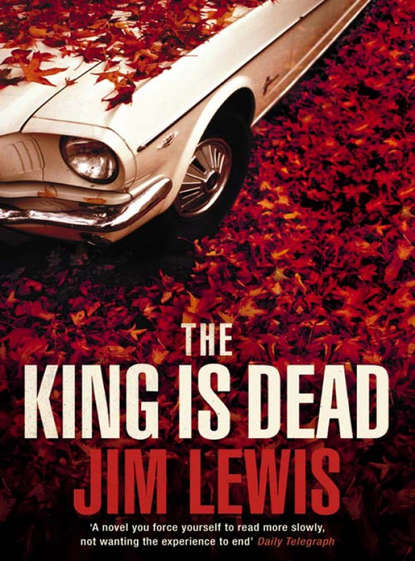

In later days they would go to the movies, and afterward he would do imitations of all the parts, the leads, the character actors, bit players, the women too, his voice cracking comically as he reached for the higher notes. Some of his impressions were startlingly accurate, and some of them were just terrible, and the worse they were the more she adored them. Then he would drive her back to her apartment, and, because she had no radio, they would sit outside her building, listening to swing while they kissed under the shadows of a tree—once for such a long time that the battery ran down, and when it was time for him to go home he couldn’t get the engine started, and he had to call out a truck to come help. After that he made sure to start the car every half hour or so, letting it idle for a few minutes while they went on with their talking, necking, talking, their raw rubbing at each other.

Oh, how much she loved that car, the shallow, intoxicating smell of its upholstery, the chrome strips—like piping on a dress—that bordered the slot where the window sat, the white cursive lettering on the dashboard and the fat round button that freed the door of the glove compartment. These were elements with which she shared her sentiment. Did he ever know? His keys hung from the ignition on a chain that passed through the center of a silver dollar, the thick disk spinning when the car shook; it was emergency money that his daddy had given him back when he first learned to drive, though when she pointed out that it might not be spendable with that hole in the middle, he just smiled as if she’d deliberately said something amusing.

He might have had some money but he had no telephone, so he would call her from a public booth in town, not always the same one; he would be standing by the railroad terminal, in the library, on a street corner. She couldn’t call him at all—she never quite knew where he was—and she grew more and more frustrated with waiting. She tried to show him but he didn’t seem to notice. He called her at home on a Thursday night at nine. I can’t talk right now, she said. Let me … she sighed. Well, I can’t call you back, can I? she said pointedly. Call me tomorrow.—And with that she hung up on him and went back to her reading, though the page in whatever it was trembled, and the letters shook themselves out of order. When he called her at work the next day, from a phone booth in a filling station, he never asked her what had kept her from him the night before. Wasn’t he curious? Didn’t he care? All that evening she was in a sullen mood: All right, she said shortly, when he suggested another movie; she sat upright in her seat in the theater, and neither stopped him nor responded when he put his hand on her arm and then slid his fingers down to her wrist, from her wrist to her knee, her knee to her thigh. He started up between her legs and still she didn’t move at all, so he withdrew.

He took her to a cocktail bar afterward; she hardly said a word the whole way there and sat across from him, rather than beside him, in the darkened booth. Are you all right? he said. He was wearing a beautiful grey shirt.

I’m fine, she said, her fingertip playing distractedly across the lip of her martini glass. She waited a moment, and then she said, I don’t think we should date anymore.

He widened his eyes and slumped back in his seat. No? he said.

I’m sorry, said Nicole. I just don’t think we should.

No? he said again, as if he was hoping that No said twice might mean Yes. Will you tell me why?

He was hurt, and whatever gratitude she might have felt for his exhibition of caring quickly gave way to guilt, so she drew back from her anger and offered him a deal. She couldn’t bear to wait by the phone, but they would be fine if he would call her regularly, at work just before noon to make plans for the evening, if plans were to be made; at home before nine if there was nothing to say but hello.

It was their first bargain, and he kept his end carefully, mornings and evenings. There was nothing romantic about the routine, not at first; it was just John calling the way he had promised he would. And then it was romantic, after all, and October turned into November.

6

Now tell me, because I don’t know, she said one afternoon. Where do you live? He had arrived at her door in his car again, and it had occurred to her, not for the first time, that she didn’t know where he was coming from. He seemed to prefer it that way; anyway, he never volunteered to tell her. If she had to ask, she would ask: Where do you live?

He shrugged. Up in the woods, a few miles out of town, west. She waited. It’s just a little house. He traced an invisible house in the air with his fluid hands. Up in the pines, about ten miles from anywhere. At night it’s so quiet, all you can hear is the wind and the wolves carrying on.

Is that right? she said with a smile. She wasn’t sure what to believe, but that was how she thought of him from then on: John-of-the-Pines when he was being quiet and sweet, John-of-the-Wolves when he had his long tongue in her mouth and his hands all over her. That was a world, and a town, and a tenure.

She told her parents she was dating a man, mentioning it to her mother in their garden one Saturday afternoon and counting on her to convey the news to her father. And what does he do? her mother had asked. She was wearing a sun hat that hid her eyes, but her tone of voice suggested that she was asking for an appraisal rather than an intimacy, as if being a lady was a business, too.

He’s with his father’s firm, said Nicole, quite startling herself with the ease with which she lied. Something to do with wood: forestry, lumber, paper, something like that.

He sounds very promising, said her mother, as she primped a gardenia. Your father will be pleased. When will we meet him?

Soon, said Nicole. We’ll make a date and I’ll bring him by, she promised, but somehow she never did.

One morning John Brice made his morning call from a booth outside the supermarket; he was in there, just wandering around the aisles, looking at all that food, and he decided on the spot to make her a dinner.

When?

I was thinking tonight, he said, and she sighed to herself, disappointed that he was treating an occasion she found momentous with such lightness of intent.

All right, she said. Tonight, then. Let me go home and get myself fixed up, and you can come by for me at seven.

Hot damn! he said suddenly. Dinner tonight! I’ll be by at seven.—And he hung up the phone before she could ask what she could bring.

At seven he was at her door, and as he walked her to the car he gestured at the paper bag she was carrying. What have you got?

A pie, she said. Store-bought, I’m sorry. And a bottle of wine.

He kissed her. Wine, oh, wine, he said, and kissed her again. Spodee-o-dee!

He took a county road back up behind the town, beating softly on the steering wheel to the rhythm of the song on the radio. In time he turned down a bowered lane, and she asked herself if it was so wise of her to have come along, after all. I don’t really know that much about him, she thought. Do I? He was leaning far back in the front seat with his knees almost resting on the dashboard, and he didn’t appear to be looking at the road at all; it was as if he were navigating by the treetops. Then he slowed and turned down a driveway, up under the trees they went, and he watched with her as his headlights swung across the front of a little gingerbread house standing in a clearing.

You don’t get to see too many houses like this anymore, he said. Not really. This was a bootlegger’s house, going back to the last century. This was where they stored the whiskey, up here in the woods. Casks of it. That’s how my granddaddy got rich. He exited his side of the car, and she stayed in her seat until he came around and opened her door, not a courtesy she would ordinarily have waited on, but it seemed appropriate to the occasion. There was a wide wind coming across the hills; it was chilly, and she shivered. He put his arm around her and began to walk her to the door. He left the place to my folks, he continued, but they don’t want to be reminded that there’s some dirty money mixed in with their nice clean cash, so they stay in Atlanta. I always knew it was here, though, and when I had to leave Georgia, I knew I was going to spend some time here.

Why did you have to leave? she said, and she stopped, as if she was going to refuse to walk any farther if there was something wrong with his answer.

He turned, serious as a funeral: They were looking for me. Because …—she stared—I shot a man in Reno.

You did what?

Now he was singing, in a hillbilly voice: Just to watch him die….

She started to back toward the car. John.

I’m joking. I’m just joking. Nicole. It’s a song, one of those new songs, he said. I didn’t have to leave. Not like that, like you’re thinking. I wasn’t in trouble. I just had to leave because I didn’t want to be there anymore.

John Brice’s house smelled of the walnut boards they’d used to build it; she noticed that as soon as they walked inside. There were four rooms: kitchen, dining room, sitting room, study. This is my place, he said. The light from the lamps was as dim as an old man’s eyesight, and the pictures on the wall were dark and dignified. It wasn’t the sort of house she expected, and then she remembered that he wasn’t the one who had decorated it; the only sign that it was his at all was a saxophone balanced against a music stand in one corner. The rest was rather gloomy. It needed a lighter touch, something a woman would do, and she allowed herself to imagine for a moment…. There’s a big old cellar that’s empty, he said, and a bedroom tucked up under the eaves, upstairs. You can’t tell it’s there from the outside, in front, but there’s a window in back. She nodded; what was this talk of bedrooms, anyway? He took her jacket and hung it on a peg on the wall.

She looked at the saxophone again. Will you play me something? she said.

Maybe later, he said, taking her by the hand and leading her into the kitchen, where he hugged her so hard she cried out and then laughed. I’ll play you something I wrote for you.

Dinner was good, she didn’t know any boys who could cook, but John Brice got together a meal, broiled some steaks with a dry rub made from his grandfather’s recipe, and made mashed potatoes. Now the wine was done. Standing in the quiet kitchen, the dishes piled in the sink, the only light coming from a fixture over the stove, and she wanted to say something to him about how lovely the evening had been, he was before her, beside her, and—how did it happen?—he was behind her, and there was a hole in the back of her that she couldn’t see and couldn’t close. It ran all the way up to her heart, which was pounding and pounding, in anticipation of being crushed. Shhh, she said, and there was quiet. She didn’t want to miss anything; she wanted to feel every fluttering of experience. Don’t worry, he said, but she wasn’t worrying.

There he was, groom and spouse. Come here, he said, although she was already in his arms. He put his hands under her blouse, resting them gently on the warm flesh of her hip. How close did he mean to come? He kissed her, more than once but less than many times; then he led her by the hand into the living room and laid her on the couch. His hand was on her breast and she tipped her head back a little bit, a reflex; she didn’t know what she wanted. He murmured something, she couldn’t make out what, and she couldn’t tell whether he wasn’t talking or she couldn’t hear. She looked all the way across the room to a window. The moon had risen away, climbing up so far that it had disappeared, there was nothing but blackness where the sky would be, and all she could sense was the smell of John’s arms, the wetness of his tongue, his murmuring beneath the noise she made when the boundary broke, the tears and gore leaking out of her, making a mess, and the wind in the trees outside.

She had helped him rend her from the word Miss. What a good sport: so lovely: what a lustful thing. She wasn’t sorry to see it happen, but she lay awake for some hours afterward, gazing on her rags and tatters, until she roused him from his sleep and insisted he take her home before morning. By the time they got back to her house the sun was nearly up and she was exhausted, really so tired she could barely make it the last few steps to the door.

The next day she found that there was little she remembered about those final aspects of the night before: the smell of walnuts, looking at herself in the bathroom mirror, and then taking a cool wet washcloth to her bloody thighs and carefully rinsing it clean in the sink when she was done. He said he had a song for her, but he hadn’t had a chance to play it, had he? She remembered his last kiss of the night, which penetrated past her mouth all the way into her skull.

7

Emily in the living room of their small apartment on Chapel Street, sipping at a gin and tonic in the dust-amber heat of a Saturday evening. Emily, who worked as an assistant at a furniture importing firm and had lunchtime trysts with the married man who managed the place. She was wearing one of his dress shirts, open to her navel, and she was giggling as Nicole described the night before. Then she resumed her usual air of lassitude. How bad was it?

It wasn’t bad at all, said Nicole. Which is not to say that I actually enjoyed it.

Did he enjoy it?—She took another sip of her drink. As long as he enjoyed it, darling. We do what we can.

Nicole frowned. I don’t know. I didn’t ask.

Oh, I’m sure he enjoyed it, said Emily. They usually do.

Speaking of which, how did you get that shirt? said Nicole. Did you send him back to the office bare-chested?

That’s one of those secret tricks we kept women have. How to build up your wardrobe, without his wife being any the wiser. I wonder if I could write that up for one of the magazines. Tips for a Fallen Angel, by Anonymous. She sipped at her drink again. So. My little Nicole has a lover.

I suppose I do, said Nicole.

Hurrah, said Emily. Another wicked girl.

I suppose I am.

Then we’ll have each other to talk to in hell. Bring along a parasol: I hear it’s hot down there.

Well, I may pay for it on Judgment Day, but I’m going to get as much from him as I can in the meantime.

Nicole! Emily laughed.

Jezebel, if you please. Jezebel, harlot, hussy, trollop, any of those will do.

Slut, said Emily, and was immediately sorry she’d said it.

But no,—Slut, said Nicole emphatically, even as she reddened at the word, and wondered if it was right.

8

On the way home one night, John Brice confessed to a future he’d obviously worked out in detail, so much so that it was more real to him than the car he was driving and the road it was on. We’re going to go out west, we two, he said. We can go to Los Angeles, get out of here. I’m going to put together a band, get a house gig at a big fancy nightclub. Get rich, live in a house up in the hills, with a hundred rooms and picture windows that look out on the lights. We’ll go to parties every night, drive down Sunset Boulevard in a big silver convertible, we’ll know the names of all the important people, and they’ll know ours.

But the whole of his speech was an opposite to her. Everything he said, when he was in that kind of mood, told her in forfeiting terms that he wasn’t the man she had been waiting for. Because she didn’t want any of that: really, not at all. He frowned a little when she failed to answer, but he didn’t say anything more. What did he care if she was silent? His will was all he needed. How did he do that? she wondered. She sometimes thought that he wanted to kill her, or at the very least, that he didn’t care whether he killed her or not.

Over the course of the following few weeks she spent almost half her nights at his house, conscious each time that she shouldn’t be there, she was opening up for something to go wrong. At first she kept forgetting to plan ahead, and she had to wear the same clothes to Clarkson’s the next day and worry that some busybody matron would notice, and know at once what she’d been doing. Then she wised up and left a dress or two at his house; her wanton clothes, they called them. Gin bottles in the liquor cabinet, red moon in the sky, songs on the radio. She had just started to get used to it, sex and all the setup it required, she had just started to enjoy it, when he tested her reach again.

He made another dinner one night in early November, a big ham, greens, cornbread, and she had only been able to eat a little of the mountain he piled on her plate. Afterward, he stood from the table, fixed her a drink, and then began to pace. Here’s what I’m thinking, he said. I have to, if I want to do…. She didn’t give him any look that helped him. It’s time, he said. It’s past time. I’ve been here, I stayed here longer, because I wanted to be with you. And I still want to be with you, but I have to go. So I’m going to go, up to New York. And I think you should come with me.

She frowned, she didn’t think he was all that serious. New York? The words meant nothing to her. I’m not going to New York, she said. I’ve never been and I’m not ready to go now. Why do you want to do that? I don’t. What do you want to go up there for?

He said, Everything I need is up there, all the people I want to meet.

People? Meet?

Other musicians, songwriters, arrangers. I can’t stay around here forever, I’ve been here too long already, I can’t stand it. It’s time for me to go.

She thought she was everyone he’d ever want to know, and she went cold, inside and out. Well, you go to New York if you want, she said. I’m not going. You go make yourself into a big man.—She made a mockery of the last two words. If he noticed he ignored it.

I want you to come with me, he said. I’m asking you to come. Nicole. Nicole. I have enough money to keep us for a while.

She shook her head. You’re crazy. Go if you want, but I’m staying here.

She thought that was the end of it; either he would go immediately and leave her to childlike Charleston, or he would stay for a while and change his mind. But she was wrong: they talked about it all through the following days; always he said he had to go, always she said she wouldn’t, and always there was the next day, the next discussion, dissection, dissension, another day of putting off disaster.

It’ll be so easy, he said, on the drive back to his house one night.

It’s not easy at all, said Nicole. My family, my friends are here. You and I are here. She waited a moment, gazing at a cream-colored quarter moon out the window on her side of the car, but he said nothing in response, and when she looked over at him his stony face was illuminated in the glare of an oncoming car.

That was December 1st, and she felt the ends of things overhanging. Three days later he disappeared, just like that. He didn’t warn her, he didn’t explain. His calls stopped coming, and she waited, she thought it was because they’d fought. But a week went by and still no word, so she borrowed a friend’s car and drove out to his house, only to find it empty and dark. Then she realized he’d left for good and without a good-bye. He’d gone to New York.

She imagined that the city had swallowed him as soon as he set his first foot down on the sidewalk. In her head New York was hell, and he was innocent but there he was. Hell, because there were so many, many people, none of them had faces, and there was no escape, and no way for them to love each other. She couldn’t imagine what kind of experiences he might be having. She tried to picture it, but all she could see was his back as he walked down the street, because he, too, had lost his features. She worried and wept; she’d never realized she was capable of such misery.

She would be tempted to ask the women who shopped in Clarkson’s: Should a woman travel to hell in order to be with a man she loves? Seven dollars and fifty cents for a girdle. Three dollars for nylon hose, beige, package of three.

9

One sunny Friday morning just after New Year’s a woman came into Clarkson’s, someone Nicole had never seen before: bleached blonde, her makeup hastily applied and unflattering, no smile and no gaze. Maybe the woman was thirty, maybe thirty-five; she shopped a little bit, she looked around at this and that. She took a dress down from its stand and turned it forward and backward to get a better look. There’s a fitting room in back, if you’d like to try that on, said Nicole. The woman merely nodded, replaced the dress, and turned away to another part of the store, where there were lacy underthings. Just about then Nicole realized they were running out of the tissue paper that they kept below the counter, so she went into the back room to get some more. When she returned the woman was gone, arid it was only an hour later, when she was going through the store, primping the stacks, that she discovered an entire shelf full of hosiery missing, and she was halfway to the stockroom for replacements before she realized that the woman must have stolen them. How very strange, the more so since they were different sizes, and so she couldn’t possibly have had any use for them all herself. Well, thought Nicole, I’ll have to tell Mr. Clarkson, and he won’t be happy about it. He can’t really blame me, though. Who would have thought a woman was a thief? It made her sad to think about it, and sadder still to think she had no one to share the story with.

10

Nicole put a sign on the door of Clarkson’s that said:

CLOSED FOR LUNCH OPEN AGAIN AT 2:00

She locked the front door and stepped out on the sidewalk. It was chilly, and the sky was shallow and grey as ashes. She hurried the few blocks home. In her mailbox there was a small lilac envelope with the address of a high school friend’s parents engraved on the back flap.—And a letter from New York City. She opened the lilac envelope immediately; it was an invitation to the girl’s wedding, and she put it down on her kitchen table and sat suddenly. Well, weren’t they all grown up? She had no way of explaining how such a thing could be happening.

She went to a tea shop for lunch; she ordered, she ate, she wondered where the new year was taking her. Back at the store, an empty afternoon, she opened John’s letter, accidentally tearing right through the return address, which was just as well: she didn’t want to know exactly where he was.

Dear Nicole:

Please forgive me because I don’t write very well. I’m sorry I left without saying good-bye. I didn’t know what to say. I love you very much but I had to leave Charleston. I wanted you to come with me, but I did not want to fight about it anymore.

New York is even bigger than I thought it would be. Yesterday I saw Robert Mitchum right on the street. I am playing with some fellows, and they are very good. I hope that someday I will see you again. Please do not be angry with me. Write to me at the address on the envelope if you want to.

Love,

John

She’d never seen his handwriting before; it was crude, unschooled, a cursive script with wide, fat loops, as if he were roping down each word. She could imagine him buying the paper at some corner store, reaching into the pocket of one of his suits for his billfold, with that funny expression he got on his face whenever he spent some money, his eyebrows raised as if the transaction was a surprise to him and he was a little bit worried that he’d get it all wrong, somehow; she could picture him sitting at his desk in some cheap hotel, brown eyes swimming; she could see him putting the letter in a mailbox and then disappearing into the crowds on Broadway; and then she couldn’t see him anymore. She folded the letter slowly, put it back in its envelope and put the envelope back in her purse. Through the plate glass in the front of the store she could see an old man in shirtsleeves and a white panama hat, shuffling off to the left.