Полная версия:

Circular economy in action: Regional adaptation of global strategies. The case of Georgia

Circular economy in action: Regional adaptation of global strategies

The case of Georgia

Leila Abdullina

© Leila Abdullina, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0065-7665-0

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

Introduction

Economic and ecological challenges of the modern world are forcing traditional approaches to be reconsidered with regard to production and consumption. Contemporary realities urge scientists, economists, and policy makers to seek solutions that could guarantee long-term sustainability of economic systems at an appropriate standard of living for current and future generations. During the last few centuries, the linear economy has been the dominant model of economic activity and is based on the principle “take-make-dispose”.

Historically, the linear economy appeared during the Industrial Revolution when mass production and consumption became the foundation of economic growth. In a time when natural resources were abundant and the costs of their extraction and processing were relatively low, the “take-make-dispose” model was advantageous and convenient for economically developed countries. The main objective was to increase the volumes of production, while the environmental consequences remained on the periphery for a long time. With the increase in population size, urbanization, and standards of living, production and consumption started to reach scales whereby the negative impacts of a linear economy manifested themselves in pollution, waste accumulation, and resource depletion. Although the linear model favored economic growth and the improvement of the quality of life, its shortcomings started to be realized during the second half of the 20th century. It has been proved to be unsustainable since it did not consider finiteness in resources, nor does it provide for waste management or any method to reduce the environmental impact. In the present scenario, a linear economy cannot provide sustainable economic growth in the present scenario without considerable environmental and health hazards.

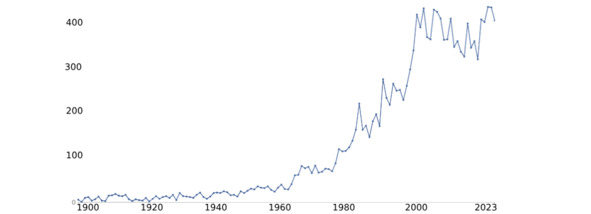

In recent decades, a linear economy has been at the core of serious environmental problems such as resource depletion, waste accumulation, and pollution. The impact is now reaching such a critical level on the planet that a transition is urgently required toward new, more environmentally sustainable models of production and consumption. The World Economic Forum and PwC estimate that almost half of the world economy, which accounts for about $44 trillion every year, relies on the state of the environment. While in 2018, 63% of mineral extraction was replaced through the discovery of new deposits, this figure fell to 32% in 2020, thus indicating the depletion of mineral resources. Further, billions of tons of waste are emitted into the environment annually, which is causing considerable effects. Frequency and intensity of natural disasters increase every year, causing large-scale economic losses and human casualties (fig.1).

Figure 1. Number of registered natural disasters worldwide [1]

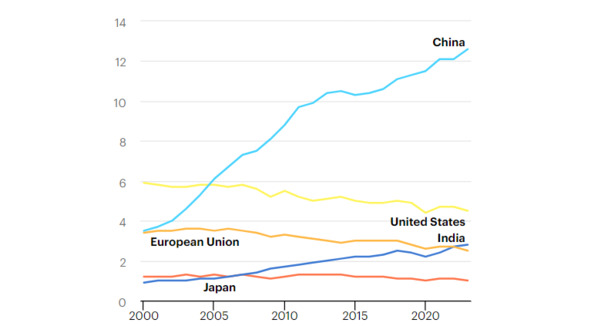

It can be witnessed that extreme weather events are intensifying and becoming more frequent, including hurricanes, floods, droughts, and wildfires. One of the driving processes is climate change, and that is greatly human-made through human activities, especially by the emission of greenhouse gases. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global CO2 emissions from the energy sector increased by 1,1% in 2023, rising by 410 million tons and reaching a new record level of 37,4 Gt. Its structure continues to evolve. Total CO2 emissions in China exceeded in 2023 that of developed economies by 15% (fig.2).

Figure 2. Total CO2 emissions by region, 2000—2023, Gt [2]

According to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), since 1880, the global temperature has risen about 1,1°C [3]. It was linked with human activities, especially burning fossil fuels and deforestation. If greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced, this temperature may increase by another 2,7°C by 2100, which will lead to disastrous consequences: sea-level rise, ecosystem destruction, and an increase in extreme weather conditions.

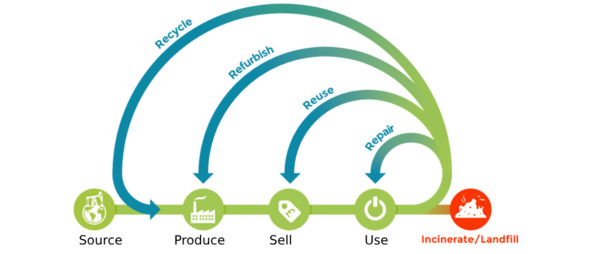

One of the promising solutions for emerging environmental and climate issues is the so-called circular economy (CE), which is one system that aims at maximum resource use with minimum waste (fig.3).

Figure 3. CE diagram

The concept of the CE is thus that of a closed loop: resources are used several times, and products, when their life cycle is over, are not wasted but recycled and reintroduced into the economic cycle [4]. Unlike the linear model, the CE assumes that materials can be used indefinitely, achieved through extending product life cycles, reusing components, and recycling materials. Transitioning to such a model requires deep transformations across all aspects of economic activity: from product design and production processes to consumer preferences. Moreover, the CE creates conditions for sustainable development by conserving resources for future generations, reducing environmental impact, and increasing economic efficiency through reduced raw material and energy costs.

The aim of this research paper is to conduct a comprehensive examination of the potential of the CE to contribute to sustainable development. It is important to assess how effectively this model will work for different countries and regions, as well as to explore how the principles of CE can be adapted and implemented in countries of different economic development levels. Further research involves three groups of countries, namely: developed economies including but not limited to the USA, European Union (EU) nations, Australia, Canada, Andorra, South Korea, and Japan; the group of emerging economies such as Russia, Georgia, Asian countries like China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Indonesia, Latin American countries, and underdeveloped regions like Haiti, Rwanda, where the application of this model faces certain unique challenges. The authors also seek to determine not only the potential benefits of CE for sustainable development but also problems and barriers to its implementation in countries with varied economic, social, and cultural characteristics.

The methodology of the study will be based on a comparative analysis of successful examples of the implementation of CE in different countries, the aggregation of data on key economic and environmental indicators, as well as an examination of legislative and regulatory initiatives. A big part of the research will be presented in the form of a critical analysis of academic works, discussing both the theoretical grounds of the CE and practical examples of its application. Among the scholars relied upon in this research are Walter R. Stahel, Michael Braungart, and Ken Webster. Their works have contributed to the formation of the CE concept and the development of strategies for its implementation that address contemporary challenges and economic needs. Moreover, the research applies methods of analysis of legislative initiatives and programs for the support of CE, statistical and empirical data regarding the effects of CE on macroeconomic and social parameters such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), employment, investments, environmental security, and quality of life. The comprehensive approach integrates data analysis with the critical reflection of scholarly works and allows seeing not only the understanding of the potential of CE but also the assessment of its significance for different countries and economic systems.

The CE represents an innovative approach, fundamentally different from the traditional linear model that underpinned industrial society. At its core, CE is based on principles that aim to use resources as efficiently as possible, minimize waste, and reduce environmental impact. One of the central principles of CE is designing products in such a way that their components can be easily recycled and reused. This calls for a different approach that considers not just the efficiency of the product in its use phase but also its disposability and recyclability after the end of its life. Walter R. Stahel [5—7] underlines that it is high time to move toward a “productive economy” in which the emphasis is shifting from volumes of production to the rational use of resources. This approach enables cost minimization and reduces environmental impact.

Another important principle is the “cradle-to-cradle” concept proposed by Michael Braungart and William McDonough [8], which aims at creating products that can be completely recycled and returned for production. This is a closed-loop principle that forms the basis for sustainable manufacturing and removes waste entirely from the economy.

Transitioning to the CE is not only an economic necessity but also an environmental one. The resource scarcity incidents, from water to rare earth metals and fossil fuels, are driving up their costs, posing serious questions regarding the sustaining of the global economy. Economies still persisting with the linear model continue to suffer from rising material costs and increased waste management and ecosystem restoration costs. In this context, CE solutions allow for more rational use of resources, reduction in emissions, and minimized environmental harm. Ken Webster’s work [9—11] points out that CE is a tool that would definitely help achieve sustainable economic growth because it reduces dependence on imported resources, minimizes environmental impact, and stimulates innovation. On a macro level, CE enhances economic stability by reusing resources and reducing disposal costs. On a micro level, companies can establish an optimal production process, reduce expenses, and ensure a more sustainable business model with a focus on long-term profitability.

The transition prospects of countries towards a CE can be highly different in countries at different levels of economic development. The classification of countries according to their development level was proposed and formalized in 1989 by international organizations like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. This classification is performed according to Gross National Income per capita.

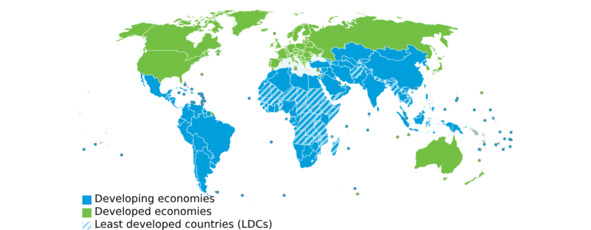

Originally, the classification was established in the mid-20th century when, after World War II, there arose a need to systematize the economic differences between countries to organize international aid and foster economic cooperation (fig. 4).

Figure 4. World by development status [12]

Developed countries, also known as high-income countries, include those that have the highest GDP per capita with a stable economic growth and advanced industrial and social infrastructure. They also enjoy a very high quality of life. The financial and institutional systems are highly developed, innovation and investment in new technologies is very active, and poverty and unemployment are relatively low. Besides, they have high standards of education, healthcare, and social services, which contribute to overall stability and resilience. Examples of developed countries include the USA, Germany, Japan, Canada, and Australia. Many developed countries are members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, founded in 1961 for the purpose of fostering economic development and the exchange of experiences among high-income nations.

The second group consists of developing countries, or countries with middle-income economies. These countries exhibit lower economic indicators compared to developed countries but show consistent economic growth. They face challenges such as poverty, income inequality, limited access to education and healthcare, as well as infrastructure deficits, which hinder further development. However, countries like Russia, Georgia, China, and Brazil, through industrialization and export activities, demonstrate improved economic indicators and are gradually transitioning towards higher-income levels.

The third group is the least developed countries, which are also known as low-income or underdeveloped countries. In these countries, there are severe social and economic problems, including low per capita GDP, underdeveloped infrastructure, high poverty, and limited availability of basic social services. Quite often, unemployment is high and educational and health facilities scarce, thus inhibiting the growth of human capital, which in turn tampers with economic stability. Examples include most sub-Saharan African countries, including Haiti and Rwanda.

In a developed country, the state level supports transitioning to circular models, actively encouraging this transition by legislative initiatives and investments in sustainable technologies. For example, in the Netherlands, CE has been recognized as a national strategy; the government has announced plans for complete implementation of CE principles by 2050. Japan also has advanced recycling and reuse technologies that help reduce waste flow and minimize environmental impact. These countries are the ones with substantial development of infrastructure, financial, and technological resources to realize circular projects at all levels of the economy.

At the same time, developing countries are also trying to include elements of the CE in their economies, although this is more difficult to do because of a number of obstacles. For instance, in Russia, the government actively supports waste disposal and recycling programs, which help reduce environmental impact and create new jobs. In Georgia, the transition to CE is supported by international funds and organizations, which undertake different measures of decreasing pollution and waste recycling. In this respect, international cooperation and access to financial resources through the World Bank and the United Nations (UN) are important for such countries to facilitate a shift toward circular models. Brazil also pays considerable attention to the integration of circular approaches into agriculture and to the recycling of plastic waste. However, complete transitioning to circular principles needs more general dissemination of knowledge and technologies, government support, and changes in legislation.

The least developed countries, especially in most regions of Africa, provide the most challenges when implementing the principles of the CE. Minimal financial resources, poor infrastructure, and heavy dependency on natural resource exports are obstacles to their transition toward closed-loop material cycles. On top of it all, these countries face other global concerns: poverty, food shortage, and limited access to basic services make the adjustment of circular practices even more difficult. The attempts at integrating the CE are further contested by resource competition and the attention that needs to be given to urgent humanitarian issues. However, the CE could still be of benefit for such countries in the form of more efficient use of local resources, a reduction in dependence on imports, and easing the environmental burden. Yet, it needs immense support from the international community through finance, expertise, and education programs to train local specialists and create the necessary recycling infrastructure. The involvement in the global CE may unlock opportunities for low-income countries in exporting recycled materials and improving economic conditions. However, this requires long-term, comprehensive efforts that not only aim at creating environmentally sustainable production processes but also address more fundamental social and economic problems.

Chapter 1. CE in developed countries

The concept of CE is gaining increasing significance in developed economies as they face challenges such as resource depletion, waste accumulation, and growing environmental concerns. The objective of this section is to understand CE through examples given by leading countries in this sphere, which have huge experience in the elaboration and implementation of sustainable economic models. Examples include the USA, EU member states, Australia, Canada, Andorra, South Korea, and Japan-all of which actively develop and promote circular principles through various government programs, legislative initiatives, and corporate strategies. The review of successful strategies shows how CE contributes to resilience enhancement and competitiveness at both the national and global market level.

These countries have realized that a transition to the CE can help improve resource scarcity, economic growth, reduced environmental impact, and uncover new economic avenues. For example, ambitious EU targets for recycling, waste reduction, and sustainable production are driving significant changes in EU industries from construction and manufacturing to consumer goods. The advance in the recycling system of Japan, fully encompassing all that waste management is, illustrates that a country has integrated circulatory into the national strategies toward reduction of ecological footprints, raising the bar in sustainability. Indeed, these examples prove that CE works in real life and therefore can become one of the ways of economic strengthening. It creates new jobs, develops an innovative technology and service sector, and ensures the long run of industries by making them independent from raw materials and energy.

As these countries keep emerging at the forefront in circular practices, their experiences provide useful lessons and frameworks for other emerging economies seeking to adopt similar models for sustainable development.

1.1. The USA

The concept of the CE in the USA is of growing importance in the context of sustainable development and rational use of resources. In recent years, there has been a marked intensification of efforts at both the federal and regional levels aimed at integrating CE principles across various sectors of the economy.

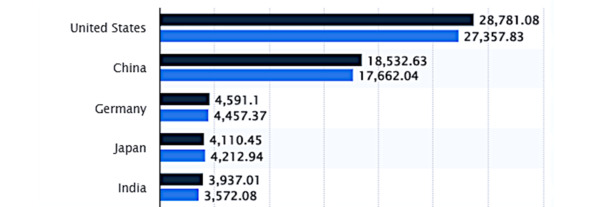

Within the USA, environmental concerns have remained one of the most critical domains of governmental policy and public interest over the past several decades. With the country ranking as the third-largest globally by both land area and population, the USA is also the world’s largest economy, with a gross domestic product of just under $29 trillion in 2024. This scale of economic activity exerts substantial pressure on natural resources and the environment (fig.5).

The evolution of the principles of CE first began in the USA as an increasing awareness of conserving natural resources and waste was evoked, largely inspired by the environmental movements of the 1960s and 1970s. In this age, societal concerns about industrialization’s environmental toll grew afresh, catalyzed by publications like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), unveiling the devastating impact of chemical pollutants on ecosystems [14]. These developments fueled public demand for action, prompting the USA government to establish the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 and introduce foundational environmental regulations. While the CE concept was not yet fully articulated, these early efforts set the stage for key practices such as recycling and resource reuse, which later became pillars of circular economic systems [15].

Figure 5. GDP levels in various countries in 2023 and 2024 [13]

Initial steps toward the incorporation of CE principles in the USA began in the 1980s and 1990s. During this period, there was much progress with recycling technologies and integrated waste management legislation. Notably, California’s Integrated Waste Management Act of 1991 required municipalities to recycle at least 25% of their waste by 1995 and 50% by 2000 [16]. These efforts thus provided a foundation for the development of recycling infrastructure and the more general diffusion of material reuse practices. Similarly, the 1994 Packaging Act mandated federal rules on the recycling and disposal of packaging materials. It marked one of the key policy shifts toward creating closed-loop systems, considering the large contribution made by packaging waste.

Starting in the early 2000s, a rash of research and innovation consistent with a CE paradigm spread through the USA. Walter R. Stahel became a key pioneer in the field, and his calls to extend product lifetimes through a “performance economy” impacted American approaches to sustainable development. Around this time, organizations like the Ellen MacArthur Foundation supported the cradle-to-cradle concept, put together by Michael Braungart and William McDonough [17]. These frameworks soon found acceptance throughout the USA and inspired the adoption of novel business models and strategies for product design focused on resource circularity, sustainable material use, and waste minimization.

In the last decade, the CE has, among others, been enjoying great interest at both the governmental and corporate levels in the USA. In the year 2018, EPA issued a Strategic Plan for Sustainable Materials Management that placed at the core of the document a presentation of the principles of circular economics. It had aimed at fiscal years 2018—2022, trying to reduce environmental impacts and enhance economic efficiency through more rational resource use at the same time [18]. CE and efficient use of materials, according to this document, have been identified as fundamental items within the agency’s agenda; the main objective has to do with mitigating environmental risks while enhancing economic performance through the use of responsible consumption and resources. EPA’s strategy was focused on shifting from a linear consumption model to a closed-loop system, which would involve waste minimization, recycling, and incorporation of the reuse and conservation of resources into processes of production and consumption.

The plan outlined three main areas of focus: protection of health and the environment, forming partnerships with public and private organizations for environmental goals, and enforcement of compliance with legislative standards with increased transparency. These focus areas included concrete measures, such as reducing the use of landfills, improving air and water quality, enhancing recycling infrastructure, and increasing the share of secondary materials in use. In this way, accelerating the transition toward CE was underpinned by partnerships with government entities, local communities, and businesses in ways that helped spread practices of recycling and the adoption of new models for resource utilization in order to reduce environmental burdens.

According to the EPA’s report, by 2018, 74% of the established targets for air and water quality were achieved [19]. Of the 92 goals, 68 were fully met, while 15% were achieved at 75—99%. Problematic metrics in air quality and chemical management were identified as areas needing further improvement. The EPA successfully streamlined hazardous waste disposal permits, reducing the backlog by 18%, achieving 136 pending permits by mid-2018. This development lessened the administrative burden and added more transparency to waste movement and processing.

The plan particularly focused on packaging wastes, which form a big fraction of municipal solid wastes (MSW) in the USA. These included strategies aimed at reducing the quantity of packaging, and advocating for the recycling of packaging material to lighten the landfills and reduce costs of managing waste. Thus, in 2018, under the Superfund program of EPA, 102 sites were completely cleaned up and 1,368 properties made available for reuse due to environmental progress in cleanups, and rehabilitation of contaminated areas.

A new strategic plan, 2022—2026, has been adopted in 2022, laying down the key objectives of the USA EPA [20]. Among the major objectives of this plan, greenhouse gas emissions reduction occupies the frontline. The agency will issue final rules by September 2026 to cut emissions from light-duty vehicles, medium- and heavy-duty trucks, power plants, and the oil and gas industry. According to an estimate, the climate partnership programs included under the plan will yield an annual reduction of 545 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalent emissions. The plan also gives much emphasis to climate adaptation, where EPA commits to assisting at least 450 federal, state, and local governments in improving resiliency to the effects of climate change. Finally, the plan proposes to reduce HFC use by 10% from the baseline levels under the AIM Act by September 2023. Other key elements of the new strategic plan include incorporating principles of equity and fairness into environmental programs and actions, as well as enhancing partnerships with federal, local, and international stakeholders.