Полная версия:

Загадочное происшествие в Стайлзе / The Mysterious Affair at Styles

‘But she had a duplicate key?’

‘Oh, yes, sir.’

Dorcas was looking very curiously at him and, to tell the truth, so was I. What was all this about a lost key? Poirot smiled.

‘Never mind, Dorcas, it is my business to know things. Is this the key that was lost?’ He drew from his pocket the key that he had found in the lock of the dispatch case upstairs.

Dorcas’s eyes looked as though they would pop out of her head.

‘That’s it, sir, right enough. But where did you find it? I looked everywhere for it.’

‘Ah, but you see it was not in the same place yesterday as it was today. Now, to pass to another subject, had your mistress a dark green dress in her wardrobe?’

Dorcas was rather startled by the unexpected question.

‘No, sir.’

‘Are you quite sure?’

‘Oh, yes, sir.’

‘Has anyone else in the house got a green dress?’ Dorcas reflected.

‘Miss Cynthia has a green evening dress.’

‘Light or dark green?’

‘A light green, sir; a sort of chiffon, they call it.’

‘Ah, that is not what I want. And nobody else has anything green?’

‘No, sir—not that I know of.’

Poirot’s face did not betray a trace of whether he was disappointed or otherwise[77]. He merely remarked:

‘Good, we will leave that and pass on. Have you any reason to believe that your mistress was likely to take a sleeping powder last night?’

‘Not last night, sir, I know she didn’t.’

‘Why do you know so positively?’

‘Because the box was empty. She took the last one two days ago, and she didn’t have any more made up.’

‘You are quite sure of that?’

‘Positive, sir.’

‘Then that is cleared up! By the way, your mistress didn’t ask you to sign any paper yesterday?’

‘To sign a paper? No, sir.’

‘When Mr Hastings and Mr Lawrence came in yesterday evening, they found your mistress busy writing letters. I suppose you can give me no idea to whom these letters were addressed?’

‘I’m afraid I couldn’t, sir. I was out in the evening. Perhaps Annie could tell you, though she’s a careless girl. Never cleared the coffee cups away last night. That’s what happens when I’m not here to look after things.’

Poirot lifted his hand.

‘Since they have been left, Dorcas, leave them a little longer, I pray you. I should like to examine them.’

‘Very well, sir.’

‘What time did you go out last evening?’

‘About six o’clock, sir.’

‘Thank you, Dorcas, that is all I have to ask you.’ He rose and strolled to the window. ‘I have been admiring these flower beds. How many gardeners are employed here, by the way?’

‘Only three now, sir. Five, we had, before the war, when it was kept as a gentleman’s place should be. I wish you could have seen it then, sir. A fair sight it was. But now there’s only old Manning, and young William, and a new-fashioned woman gardener in breeches and such-like[78]. Ah, these are dreadful times!’

‘The good times will come again, Dorcas. At least, we hope so. Now, will you send Annie to me here?’

‘Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.’

‘How did you know that Mrs Inglethorp took sleeping powders?’ I asked, in lively curiosity, as Dorcas left the room. ‘And about the lost key and the duplicate?’

‘One thing at a time[79]. As to the sleeping powders, I knew by this.’ He suddenly produced a small cardboard box, such as chemists use for powders[80].

‘Where did you find it?’

‘In the wash-stand drawer in Mrs Inglethorp’s bedroom. It was Number Six of my catalogue.’

‘But I suppose, as the last powder was taken two days ago, it is not of much importance?’

‘Probably not, but do you notice anything that strikes you as peculiar about this box?’

I examined it closely.

‘No, I can’t say that I do.’

‘Look at the label.’

I read the label carefully: ‘“One powder to be taken at bedtime, if required. Mrs Inglethorp.” No, I see nothing unusual.’

‘Not the fact that there is no chemist’s name?’

‘Ah!’ I exclaimed. ‘To be sure, that is odd!’

‘Have you ever known a chemist to send out a box like that, without his printed name?’

‘No, I can’t say that I have.’

I was becoming quite excited, but Poirot damped my ardour by remarking[81]:

‘Yet the explanation is quite simple. So do not intrigue yourself, my friend.’

An audible creaking proclaimed the approach of Annie, so I had no time to reply.

Annie was a fine, strapping girl, and was evidently labouring under intense excitement, mingled with a certain ghoulish enjoyment of the tragedy.

Poirot came to the point at once, with a business-like briskness.

‘I sent for you, Annie, because I thought you might be able to tell me something about the letters Mrs Inglethorp wrote last night. How many were there? And can you tell me any of the names and addresses?’

Annie considered.

‘There were four letters, sir. One was to Miss Howard, and one was to Mr Wells, the lawyer, and the other two I don’t think I remember, sir—oh, yes, one was to Ross’s, the caterers in Tadminster. The other one, I don’t remember.’

‘Think,’ urged Poirot.

Annie racked her brains in vain[82].

‘I’m sorry, sir, but it’s clean gone. I don’t think I can have noticed it.’

‘It does not matter,’ said Poirot, not betraying any sign of disappointment. ‘Now I want to ask you about something else. There is a saucepan in Mrs Inglethorp’s room with some cocoa in it. Did she have that every night?’

‘Yes, sir, it was put in her room every evening, and she warmed it up in the night—whenever she fancied it.’

‘What was it? Plain cocoa?’

‘Yes, sir, made with milk, with a teaspoonful of sugar, and two teaspoonfuls of rum in it.’

‘Who took it to her room?’

‘I did, sir.’

‘Always?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘At what time?’

‘When I went to draw the curtains, as a rule, sir.’

‘Did you bring it straight up from the kitchen then?’

‘No, sir, you see there’s not much room on the gas stove, so Cook used to make it early, before putting the vegetables on for supper. Then I used to bring it up, and put it on the table by the swing door, and take it into her room later.’

‘The swing door is in the left wing, is it not?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And the table, is it on this side of the door, or on the further—servants’ side?’

‘It’s this side, sir.’

‘What time did you bring it up last night?’

‘About quarter past seven, I should say, sir.’

‘And when did you take it into Mrs Inglethorp’s room?’

‘When I went to shut up, sir. About eight o’clock. Mrs Inglethorp came up to bed before I’d finished.’

‘Then, between seven-fifteen and eight o’clock, the cocoa was standing on the table in the left wing?’

‘Yes, sir.’ Annie had been growing redder and redder in the face, and now she blurted out unexpectedly:

‘And if there was salt in it, sir, it wasn’t me. I never took the salt near it.’

‘What makes you think there was salt in it?’ asked Poirot.

‘Seeing it on the tray, sir.’

‘You saw some salt on the tray?’

‘Yes. Coarse kitchen salt, it looked. I never noticed it when I took the tray up, but when I came to take it into the mistress’s room I saw it at once, and I suppose I ought to have taken it down again, and asked Cook to make some fresh. But I was in a hurry, because Dorcas was out, and I thought maybe the cocoa itself was all right, and the salt had only gone on the tray. So I dusted it off with my apron, and took it in.’

I had the utmost difficulty in controlling my excitement. Unknown to herself, Annie had provided us with an important piece of evidence. How she would have gaped if she had realized that her ‘coarse kitchen salt’ was strychnine, one of the most deadly poisons known to mankind. I marvelled at Poirot’s calm. His self-control was astonishing. I awaited his next question with impatience, but it disappointed me.

‘When you went into Mrs Inglethorp’s room, was the door leading into Miss Cynthia’s room bolted?’

‘Oh! Yes, sir; it always was. It had never been opened.’

‘And the door into Mr Inglethorp’s room? Did you notice if that was bolted too?’

Annie hesitated.

‘I couldn’t rightly say, sir; it was shut but I couldn’t say whether it was bolted or not.’

‘When you finally left the room, did Mrs Inglethorp bolt the door after you?’

‘No, sir, not then, but I expect she did later. She usually did lock it at night. The door into the passage, that is.’

‘Did you notice any candle grease on the floor when you did the room yesterday?’

‘Candle grease? Oh, no, sir. Mrs Inglethorp didn’t have a candle, only a reading lamp.’

‘Then, if there had been a large patch of candle grease on the floor, you think you would have been sure to have seen it?’

‘Yes, sir, and I would have taken it out with a piece of blotting paper and a hot iron.’

Then Poirot repeated the question he had put to Dorcas:

‘Did your mistress ever have a green dress?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Nor a mantle, nor a cape, nor a—how do you call it?—a sports coat?’

‘Not green, sir.’

‘Nor anyone else in the house?’

Annie reflected.

‘No, sir.’

‘You are sure of that?’

‘Quite sure.’

‘Bien![83] That is all I want to know. Thank you very much.’

With a nervous giggle, Annie took herself creakingly out of the room. My pent-up excitement burst forth[84].

‘Poirot,’ I cried, ‘I congratulate you! This is a great discovery.’

‘What is a great discovery?’

‘Why, that it was the cocoa and not the coffee that was poisoned. That explains everything! Of course it did not take effect until the early morning, since the cocoa was only drunk in the middle of the night.’

‘So you think that the cocoa—mark well what I say, Hastings, the cocoa—contained strychnine?’

‘Of course! That salt on the tray, what else could it have been?’

‘It might have been salt,’ replied Poirot placidly.

I shrugged my shoulders. If he was going to take the matter that way, it was no good arguing with him. The idea crossed my mind, not for the first time, that poor old Poirot was growing old. Privately I thought it lucky that he had associated with him someone of a more receptive type of mind.

Poirot was surveying me with quietly twinkling eyes.

‘You are not pleased with me, mon ami ?’

‘My dear Poirot,’ I said coldly, ‘it is not for me to dictate to you. You have a right to your own opinion, just as I have to mine.’

‘A most admirable sentiment,’ remarked Poirot, rising briskly to his feet. ‘Now I have finished with this room. By the way, whose is the smaller desk in the corner?’

‘Mr Inglethorp’s.’

‘Ah!’ He tried the roll top tentatively. ‘Locked. But perhaps one of Mrs Inglethorp’s keys would open it.’ He tried several, twisting and turning them with a practised hand, and finally uttering an ejaculation of satisfaction. ‘Voilà![85] It is not the key, but it will open it at a pinch.’ He slid back the roll top, and ran a rapid eye over the neatly filed papers. To my surprise, he did not examine them, merely remarking approvingly as he relocked the desk: ‘Decidedly, he is a man of method, this Mr Inglethorp!’

A ‘man of method’ was, in Poirot’s estimation, the highest praise that could be bestowed on any individual.

I felt that my friend was not what he had been as he rambled on disconnectedly:

‘There were no stamps in his desk, but there might have been, eh, mon ami? There might have been? Yes’—his eyes wandered round the room—‘this boudoir has nothing more to tell us. It did not yield much. Only this.’

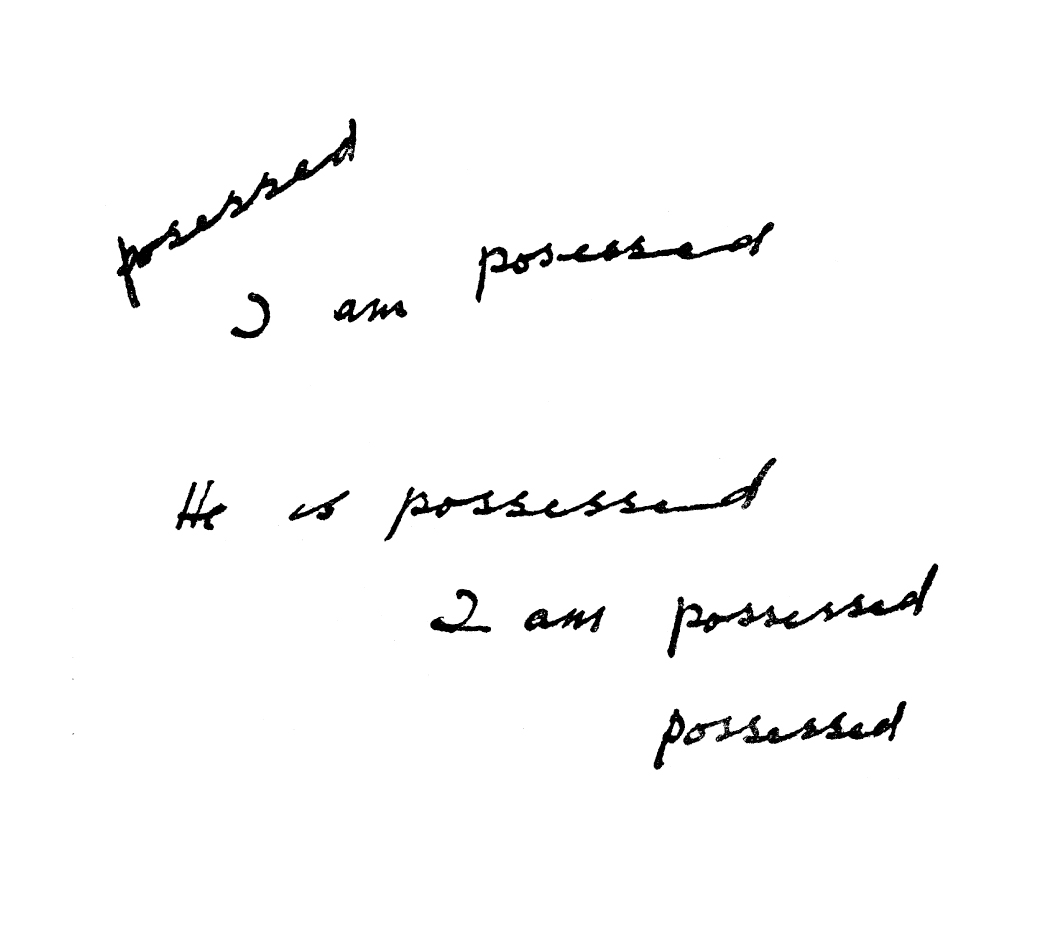

He pulled a crumpled envelope out of his pocket, and tossed it over to me. It was rather a curious document. A plain, dirty-looking old envelope with a few words scrawled across it, apparently at random.

The following is a facsimile of it[86]:

CHAPTER 5. ‘It isn’t Strychnine, is it?’

‘Where did you find this?’ I asked Poirot, in lively curiosity.

‘In the waste-paper basket. You recognize the handwriting?’

‘Yes, it is Mrs Inglethorp’s. But what does it mean?’

Poirot shrugged his shoulders.

‘I cannot say—but it is suggestive.’

A wild idea flashed across me. Was it possible that Mrs Inglethorp’s mind was deranged? Had she some fantastic idea of demoniacal possession[87]? And, if that were so, was it not also possible that she might have taken her own life?

I was about to expound these theories to Poirot, when his own words distracted me.

‘Come,’ he said, ‘now to examine the coffee cups!’

‘My dear Poirot! What on earth is the good of that, now that we know about the cocoa?’

‘Oh, là là![88] That miserable cocoa!’ cried Poirot flippantly.

He laughed with apparent enjoyment, raising his arms to heaven in mock despair, in what I could not but consider the worst possible taste.

‘And, anyway,’ I said, with increasing coldness, ‘as Mrs Inglethorp took her coffee upstairs with her, I do not see what you expect to find, unless you consider it likely that we shall discover a packet of strychnine on the coffee tray!’

Poirot was sobered at once.

‘Come, come, my friend,’ he said, slipping his arm through mine. ‘Ne vous fâchez pas![89] Allow me to interest myself in my coffee cups, and I will respect your cocoa. There! Is it a blotting?’

He was so quaintly humorous that I was forced to laugh; and we went together to the drawing room, where the coffee cups and tray remained undisturbed as we had left them.

Poirot made me recapitulate the scene of the night before, listening very carefully, and verifying the position of the various cups.

‘So Mrs Cavendish stood by the tray—and poured out. Yes. Then she came across to the window where you sat with Mademoiselle Cynthia. Yes. Here are the three cups. And the cup on the mantelpiece, half drunk, that would be Mr Lawrence Cavendish’s. And the one on the tray?’

‘John Cavendish’s. I saw him put it down there.’

‘Good. One, two, three, four, five—but where, then, is the cup of Mr Inglethorp?’

‘He does not take coffee.’

‘Then all are accounted for. One moment, my friend.’

With infinite care, he took a drop or two from the grounds in each cup, sealing them up in separate test tubes, tasting each in turn as he did so. His physiognomy underwent a curious change. An expression gathered there that I can only describe as half puzzled, and half relieved.

‘Bien!’ he said at last. ‘It is evident! I had an idea—but clearly I was mistaken. Yes, altogether I was mistaken. Yet it is strange. But no matter!’

And, with a characteristic shrug, he dismissed whatever it was that was worrying him from his mind. I could have told him from the beginning that this obsession of his over the coffee was bound to end in a blind alley[90], but I restrained my tongue. After all, though he was old, Poirot had been a great man in his day.

‘Breakfast is ready,’ said John Cavendish, coming in from the hall. ‘You will breakfast with us, Monsieur Poirot?’

Poirot acquiesced. I observed John. Already he was almost restored to his normal self. The shock of the events of the last night had upset him temporarily, but his equable poise soon swung back to the normal. He was a man of very little imagination, in sharp contrast with his brother, who had, perhaps, too much.

Ever since the early hours of the morning, John had been hard at work, sending telegrams—one of the first had gone to Evelyn Howard—writing notices for the papers, and generally occupying himself with the melancholy duties that a death entails.

‘May I ask how things are proceeding?’ he said. ‘Do your investigations point to my mother having died a natural death—or—or must we prepare ourselves for the worst?’

‘I think, Mr Cavendish,’ said Poirot gravely, ‘that you would do well not to buoy yourself up with any false hopes[91]. Can you tell me the views of the other members of the family?’

‘My brother Lawrence is convinced that we are making a fuss over nothing. He says that everything points to its being a simple case of heart failure.’

‘He does, does he? That is very interesting—very interesting,’ murmured Poirot softly. ‘And Mrs Cavendish?’

A faint cloud passed over John’s face.

‘I have not the least idea what my wife’s views on the subject are.’

The answer brought a momentary stiffness in its train. John broke the rather awkward silence by saying with a slight effort:

‘I told you, didn’t I, that Mr Inglethorp has returned?’

Poirot bent his head.

‘It’s an awkward position for all of us. Of course one has to treat him as usual—but, hang it all[92], one’s gorge does rise[93] at sitting down to eat with a possible murderer!’

Poirot nodded sympathetically.

‘I quite understand. It is a very difficult situation for you, Mr Cavendish. I would like to ask you one question. Mr Inglethorp’s reason for not returning last night was, I believe, that he had forgotten the latchkey. Is not that so?’

‘Yes.’

‘I suppose you are quite sure that the latchkey was forgotten—that he did not take it after all?’

‘I have no idea. I never thought of looking. We always keep it in the hall drawer. I’ll go and see if it’s there now.’

Poirot held up his hand with a faint smile.

‘No, no, Mr Cavendish, it is too late now. I am certain that you will find it. If Mr Inglethorp did take it, he has had ample time to replace it by now.’

‘But do you think—’

‘I think nothing. If anyone had chanced to look this morning before his return, and seen it there, it would have been a valuable point in his favour. That is all.’

John looked perplexed.

‘Do not worry,’ said Poirot smoothly. ‘I assure you that you need not let it trouble you. Since you are so kind, let us go and have some breakfast.’

Everyone was assembled in the dining room. Under the circumstances, we were naturally not a cheerful party. The reaction after a shock is always trying, and I think we were all suffering from it. Decorum and good breeding naturally enjoined that our demeanour should be much as usual, yet I could not help wondering if this self-control were really a matter of great difficulty. There were no red eyes, no signs of secretly indulged grief. I felt that I was right in my opinion that Dorcas was the person most affected by the personal side of the tragedy.

I pass over Alfred Inglethorp, who acted the bereaved widower in a manner that I felt to be disgusting in its hypocrisy. Did he know that we suspected him, I wondered. Surely he could not be unaware of the fact, conceal it as we would. Did he feel some secret stirring of fear, or was he confident that his crime would go unpunished? Surely the suspicion in the atmosphere must warn him that he was already a marked man.

But did everyone suspect him? What about Mrs Cavendish? I watched her as she sat at the head of the table, graceful, composed, enigmatic. In her soft grey frock, with white ruffles at the wrists falling over her slender hands, she looked very beautiful. When she chose, however, her face could be sphinx-like in its inscrutability. She was very silent, hardly opening her lips, and yet in some queer way I felt that the great strength of her personality was dominating us all.

And little Cynthia? Did she suspect? She looked very tired and ill, I thought. The heaviness and languor of her manner were very marked. I asked her if she were feeling ill, and she answered frankly:

‘Yes, I’ve got the most beastly headache.’

‘Have another cup of coffee, mademoiselle?’ said Poirot solicitously. ‘It will revive you. It is unparalleled for the mal de tête[94].’ He jumped up and took her cup.

‘No sugar,’ said Cynthia, watching him, as he picked up the sugar tongs.

‘No sugar? You abandon it in the wartime, eh?’

‘No, I never take it in coffee.’

‘Sacré![95]’ murmured Poirot to himself, as he brought back the replenished cup.

Only I heard him, and glancing up curiously at the little man I saw that his face was working with suppressed excitement, and his eyes were as green as a cat’s. He had heard or seen something that had affected him strongly—but what was it? I do not usually label myself as dense, but I must confess that nothing out of the ordinary had attracted my attention.

In another moment, the door opened and Dorcas appeared.

‘Mr Wells to see you, sir,’ she said to John.

I remembered the name as being that of the lawyer to whom Mrs Inglethorp had written the night before.

John rose immediately.

‘Show him into my study.’ Then he turned to us. ‘My mother’s lawyer,’ he explained. And in a lower voice: ‘He is also Coroner—you understand. Perhaps you would like to come with me?’

We acquiesced and followed him out of the room. John strode on ahead and I took the opportunity of whispering to Poirot:

‘There will be an inquest then?’

Poirot nodded absently. He seemed absorbed in thought[96]; so much so that my curiosity was aroused.

‘What is it? You are not attending to what I say.’

‘It is true, my friend. I am much worried.’

‘Why?’

‘Because Mademoiselle Cynthia does not take sugar in her coffee.’

‘What? You cannot be serious?’

‘But I am most serious. Ah, there is something there that I do not understand. My instinct was right.’

‘What instinct?’

‘The instinct that led me to insist on examining those coffee cups. Chut![97] no more now!’

We followed John into his study, and he closed the door behind us.

Mr Wells was a pleasant man of middle-age, with keen eyes, and the typical lawyer’s mouth. John introduced us both, and explained the reason of our presence.

‘You will understand, Wells,’ he added, ‘that this is all strictly private. We are still hoping that there will turn out to be no need for investigation of any kind.’

‘Quite so, quite so,’ said Mr Wells soothingly. ‘I wish we could have spared you the pain and publicity of an inquest, but, of course, it’s quite unavoidable in the absence of a doctor’s certificate.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

invalided home from the Front – демобилизован с фронта по случаю ранения

2

given a month’s sick leave – получил месяц отпуска для восстановления

3

Lady Bountiful – леди Баунтифул, т. е. щедрая благодетельница (по имени персонажа пьесы Дж. Фаркера «Уловка кавалеров»).

4

country-place – загородная усадьба

5

He had been completely under his wife’s ascendancy. – Он находился полностью под влиянием своей жены.

6

she certainly had the whip hand, namely: the purse strings – учитывая ее достаток, она могла рассчитывать на уважение

7

rotten little bounder – гнусный маленький пройдоха

8

Jack of all trades – мастерица на все руки

9

protégée – (фр.) протеже, подопечная

10

He came a cropper. – Он прогорел (потерпел крах).

11

Her conversation <…> was couched in the telegraphic style. – Ее манера изъясняться напоминала телеграфный стиль.

12

The labourer is worthy of his hire. – Трудящийся достоин награды за труды свои (цитата из Евангелия, Лк 10:7).

13

slumbering fire – заградительный огонь

14

fête – (фр.) вечеринка, праздник

15