Полная версия:

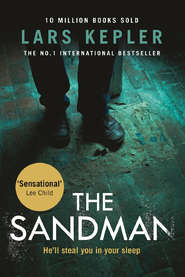

The Sandman

He coughs, leans his head back and closes his eyes.

‘You said something about how it was in the beginning,’ Joona says. ‘Can you try—’

‘Don’t touch me, I don’t want you to touch me,’ he interrupts.

‘I’m not going to.’

‘I don’t want to, I don’t want to, I can’t, I don’t want to …’

His eyes roll back and he tilts his head in an odd, crooked way, then shuts his eyes and his body trembles.

‘There’s no danger,’ Joona repeats.

After a while Mikael’s body relaxes again, and he coughs and looks up.

‘Can you tell me anything about how it was in the beginning?’ Joona repeats gently.

‘When I was little … we were huddled together on the floor,’ he says, almost soundlessly.

‘So there were several of you at the start?’ Joona asks, a shiver running up his spine and making the hairs on the back of his neck stand on end.

‘Everyone was frightened … I was calling for Mum and Dad … and there was a grown-up woman and an old man on the floor … they were sitting on the floor behind the sofa … She tried to calm me down, but … but I could hear her crying the whole time.’

‘What did she say?’ Joona asks.

‘I don’t remember, I don’t remember anything, maybe I dreamed the whole thing …’

‘You just mentioned an old man and a woman.’

‘No.’

‘Behind the sofa,’ Joona says.

‘No,’ Mikael whispers.

‘Do you remember any names?’

He coughs and shakes his head.

‘Everyone was just crying and screaming, and the woman with the eye kept asking about two boys,’ he says, his eyes focused inwardly.

‘Do you remember any names?’

‘What?’

‘Do you remember the names of—’

‘I don’t want to, I don’t want to …’

‘I’m not trying to upset you, but—’

‘They all disappeared, they just disappeared,’ Mikael says, his voice getting louder. ‘They all disappeared, they all …’

Mikael’s voice cracks, and it’s no longer possible to make out what he’s saying.

Joona repeats that everything is going to be all right. Mikael looks him in the eye, but he’s shaking so much he can’t speak.

‘You’re safe here,’ Joona says. ‘I’m a police officer, and I’ll make sure that nothing happens to you.’

Dr Irma Goodwin comes into the room with a nurse. They walk over to the patient and gently put his oxygen mask back on. The nurse injects the sedative solution into the drip while calmly explaining what she’s doing.

‘He needs to rest now,’ the doctor says to Joona.

‘I need to know what he saw.’

She tilts her head and rubs her ring finger.

‘Is it very urgent?’

‘No,’ Joona replies. ‘Not really.’

‘Come back tomorrow, then,’ Irma says. ‘Because I think—’

Her mobile rings and she has a short conversation, then hurries out of the room. Joona is left standing by the bed as he hears her vanish down the corridor.

‘Mikael, what did you mean about the eye? You mentioned the woman with the eye – what did you mean?’ he asks slowly.

‘It was like … like a black teardrop …’

‘Her pupil?’

‘Yes,’ Mikael whispers, then shuts his eyes.

Joona looks at the young man in the bed, feeling his pulse roar in his temples, and his voice is brittle and metallic as he asks:

‘Was her name Rebecka?’

34

Mikael is crying as the sedative enters his bloodstream. His body relaxes, his sobbing grows more weary, then subsides completely seconds before he drifts off to sleep.

Joona feels oddly empty inside as he leaves the patient’s room and pulls out his phone. He stops, pauses for breath, then calls Åhlén, who carried out the extensive forensic autopsies on the bodies found in Lill-Jan’s Forest.

‘Nils Åhlén,’ he says as he takes the call.

‘Are you sitting at your computer?’

‘Joona Linna, how nice to hear from you,’ Åhlén says in his nasal voice. ‘I was just sitting here in front of the screen with my eyes closed, enjoying its warmth. I was fantasising that I’d bought a facial solarium.’

‘Elaborate daydream.’

‘Well, if you look after the pennies …’

‘Would you like to look up some old files?’

‘Talk to Frippe, he’ll help you.’

‘No can do.’

‘He knows as much as—’

‘It’s about Jurek Walter,’ Joona interrupts.

A long silence follows.

‘I’ve told you, I don’t want to talk about that again,’ Åhlén says calmly.

‘One of his victims has turned up alive.’

‘Don’t say that.’

‘Mikael Kohler-Frost … He’s got Legionnaires’ disease, but it looks as though he’s going to pull through.’

‘What are the files you’re interested in?’ Åhlén asks with nervous intensity in his voice.

‘The man in the barrel had Legionnaires’ disease,’ Joona goes on. ‘But did the boy who was found with him show any signs of the disease?’

‘Why are you wondering that?’

‘If there’s a connection, it ought to be possible to put together a list of places where the bacteria might be present. And then—’

‘We’re talking about millions of places,’ Åhlén interrupts.

‘OK …’

‘Joona. You have to realise, even if Legionella was mentioned in the other reports, that doesn’t mean that Mikael was one of Jurek Walter’s victims.’

‘So there were Legionella bacteria?’

‘Yes, I found antibodies against the bacteria in the boy’s blood, so he’d probably had Pontiac fever,’ Åhlén says with a sigh. ‘I know you want to be right, Joona, but nothing you’ve said is enough to—’

‘Mikael Kohler-Frost says he met Rebecka,’ Joona interrupts.

‘Rebecka Mendel?’ Åhlén asks with a tremble in his voice.

‘They were held captive together,’ Joona confirms.

There is a long silence, then: ‘So … so you were right about everything, Joona,’ Åhlén says, sounding as if he’s about to start crying. ‘You’ve no idea how relieved I am to hear that.’

He gulps hard down the phone, and whispers that they did the right thing after all.

‘Yes,’ Joona says, in a lonely voice.

He and Åhlén had done the right thing when they arranged the car-crash for Joona’s wife and daughter.

Two dead bodies were cremated and buried in place of Lumi and Summa. Using fake dental records, Åhlén had identified the bodies. He believed Joona, and trusted him, but it had been such a big decision, so momentous, that he has never stopped worrying about it.

Joona daren’t leave the hospital until two uniformed officers arrive to guard Mikael’s room. On his way out along the corridor he calls Nathan Pollock and says they need to send someone to pick up the man’s father.

‘I’m sure it’s Mikael,’ he says. ‘And I’m sure he’s been held captive by Jurek Walter all these years.’

He gets in the car and slowly drives away from the hospital as the windscreen wipers clear the snow aside.

Mikael Kohler-Frost was ten years old when he disappeared – and he was twenty-three when he managed to escape.

Sometimes prisoners manage to escape, like Elisabeth Fritzl in Austria, who escaped after twenty-four years as a sex-slave in her father’s cellar. Or Natascha Kampusch, who fled her kidnapper after eight years.

Joona can’t help thinking that, like Elisabeth Fritzl and Natascha Kampusch, Mikael must have seen the man holding him captive. Suddenly a conclusion to all this seems possible. In just a few days, as soon as he is well enough, Mikael ought to be able to show the way to the place where he was held captive for so long.

The car’s tyres rumble as Joona crosses the ridge of snow in the middle of the road to overtake a bus. As he drives past the Palace of Nobility the city opens up in front of him once more, with heavy snow falling between the dark sky and the swirling black water below the bridge.

Obviously the accomplice must know that Mikael has escaped and can identify him, Joona thinks. Presumably he has already tried to cover his tracks and switch to a new hiding place, but if Mikael can lead them to where he was held captive, Forensics would be able to find some sort of evidence and the hunt would be on again.

There’s a long way to go, but Joona’s heart is already beating faster in his chest.

The thought is so overwhelming that he has to pull over to the side of Vasa Bridge and stop the car. Another driver blows his horn irritably. Joona gets out of his car and steps up onto the pavement, breathing the cold air deep into his lungs.

A sudden burst of migraine makes him stumble and he grabs the railing for support. He closes his eyes for a moment, waits, and feels the pain ebb away before he opens his eyes again.

Millions and millions of white snowflakes are flying through the air, vanishing on the dark water as if they had never existed.

It’s too early to dare to think the thought, but he is well aware of what this means. His body feels weighed down by the realisation. If he manages to catch the accomplice, there will no longer be any threat to Summa and Lumi.

35

It’s too hot to talk in the sauna. Gold-coloured light is shining on their naked bodies and the pale sandalwood. It’s 97 degrees now and the air burns Reidar Frost’s lungs when he breathes in. Drops of sweat are falling from his nose onto the white hair on his chest.

The Japanese journalist, Mizuho, is sitting on the bench next to Veronica. Their bodies are both flushed and shiny. Sweat is running between their breasts, over their stomachs and down into their pubic hair.

Mizuho is looking seriously at Reidar. She has come all the way from Tokyo to interview him. He told her good-naturedly that he never gives interviews, but that she was very welcome to attend the party. She was probably hoping he would say something about the Sanctum series being turned into a manga film. She has been here four days now.

Veronica sighs and closes her eyes for a while.

Mizuho didn’t take off her gold necklace before entering the sauna, and Reidar can see that it’s starting to burn. Marie only lasted five minutes before she went off to the shower, and now the Japanese journalist leaves the sauna as well.

Veronica leans forward and rests her elbows on her knees, breathing through her half-open mouth as sweat drips from her nipples.

Reidar feels a sort of brittle tenderness towards her. But he doesn’t know how to explain the desolate landscape inside him, and that everything he does now, everything he throws himself into, is just random fumbling for something to help him survive the next minute.

‘Marie’s very beautiful,’ Veronica says.

‘Yes.’

‘Big breasts.’

‘Stop it,’ Reidar mutters.

She looks at him with a serious expression as she goes on:

‘Why can’t I just get a divorce …?’

‘Because that would be the end for us,’ Reidar says.

Veronica’s eyes fill with tears and she is about to say something else when Marie comes back in and sits down next to Reidar with a little giggle.

‘God, it’s hot,’ she gasps. ‘How can you sit here?’

Veronica throws a scoop of water onto the stones. There’s a loud hiss and hot clouds of steam rise up and surround them for a few seconds. Then the heat becomes dry and static again.

Reidar is hanging forward over his knees. The hair on his head is so hot he almost scalds himself when he runs his hand through it.

‘No, that’s enough,’ he gasps, and climbs down.

The two women follow him out into the soft snow. Dusk is spreading its darkness across the snow, which is already glowing pale blue.

Heavy snowflakes drift down as the three naked people pound through the deep snow.

David, Wille and Berzelius are eating dinner with the other members of the Sanctum scholarship committee, and the drinking songs can be heard all the way out to the back of the garden.

Reidar turns and looks at Veronica and Marie. Steam is rising from their flushed bodies, they’re enveloped in veils of mist as the snow falls around them. He is about to say something when Veronica bends over and throws an armful of snow up at him. He backs away, laughing, and falls onto his back, vanishing under the loose snow.

He lies there on his back, listening to their laughter.

The snow feels liberating. His body is still scorching hot. Reidar looks straight up at the sky, the hypnotic snow falling from the centre of creation, an eternity of drifting white.

A memory takes him by surprise. He is peeling off the children’s snowsuits. Taking off hats with snow caught in the wool. He can remember their cold cheeks and sweaty hair. The smell of the drying cupboard and wet boots.

He misses the children so much that his longing feels purely physical in its intensity.

Right now he wishes he was alone, so he could lie in the snow until he lost consciousness. Die, surrounded by his memories of Felicia and Mikael. Of how they had once been his.

He gets to his feet with an effort and gazes out across the white fields. Marie and Veronica are laughing, making angels in the snow and rolling around a short distance away.

‘How long have these parties been going on?’ Marie calls to him.

‘I don’t want to talk about it,’ Reidar mumbles.

He is about to walk off, drink until he’s drunk, then tie a noose round his neck, but Marie is standing in front of him, legs akimbo.

‘You never want to talk. I don’t know anything,’ she says with a laugh. ‘I don’t even know if you’ve got children, or—’

‘Just leave me the fuck alone!’ Reidar shouts, and pushes past. ‘What is it you want?’

‘Sorry, I …’

‘Leave me the fuck alone,’ he snaps, and disappears into the house.

The two women walk shivering back into the sauna. The steam on their bodies runs off as the heat closes round them again, as if it had never been gone.

‘What’s his problem?’ Marie asks.

‘He’s pretending to be alive, but feels dead,’ Veronica replies simply.

36

Reidar Frost is wearing a new pair of trousers with a double stripe, and an open shirt. The back of his hair is damp. He is clutching a bottle of Château Mouton Rothschild in each hand.

That morning he had been on his way to the room upstairs to remove the rope from the beam, but when he reached the door he had been filled instead with an aching sense of longing. He stood with his hand on the door handle and forced himself to turn round, go downstairs and wake his friends. They poured spiced schnapps into crystal glasses and rustled up some boiled eggs with Russian caviar.

Reidar is walking barefoot along a corridor lined with dark portraits.

The snow outside is casting an indirect light, like a pale darkness.

In the reading room with its shiny leather furniture he stops and looks out of the huge window. The view is like a fairytale. As if the king of winter had blown snow across a landscape of apple trees and fields.

Suddenly he sees flickering lights on the long avenue leading from the gates to the front of the house. The branches of the trees look like embroidered lace in the glow. A car approaching. The snow swirling into the air behind it is coloured red by its rear-lights.

Reidar can’t recall inviting anyone else to join them.

He is just thinking that Veronica will have to take care of the new arrivals when he sees that it’s a police car.

Reidar stops and puts the bottles down on a chest, then goes back downstairs and pulls on the felt-lined winter boots beside the door. He heads out into the cold air to meet the car as it arrives in the broad turning circle.

‘Reidar Frost?’ a woman in plain clothes says as she gets out of the car.

‘Yes,’ he replies.

‘Can we go inside?’

‘Here will do,’ he says.

‘Would you like to sit in the car?’

‘Does it look like it?’

‘We’ve found your son,’ the woman says, taking a couple of steps towards him.

‘I see,’ he sighs, holding up a hand to silence the police officer.

He is breathing, feeling the smell of the snow, of water that has frozen to ice high up in the sky. Reidar composes himself, then slowly lowers his hand.

‘So where did you find Mikael?’ he says in a voice that has become strangely calm.

‘He was walking over a bridge—’

‘What?! What the hell are you saying, woman?’ Reidar roars.

The woman flinches. She’s tall, and has a long ponytail down her back.

‘I’m trying to tell you that he’s alive,’ she says.

‘What is this?’ Reidar asks uncomprehendingly.

‘He’s been taken into Södermalm Hospital for observation.’

‘Not my son, he died many years—’

‘There’s no doubt whatsoever that it’s him.’

Reidar is staring at her with eyes that have turned completely black.

‘Mikael’s alive?’

‘He’s come back.’

‘My son?’

‘I appreciate that it’s strange, but—’

‘I thought …’

Reidar’s chin trembles as the policewoman explains that his DNA is a one hundred per cent match. The ground beneath him feels soft, rolling like a wave, and he fumbles in the air for support.

‘Sweet God in heaven,’ he whispers. ‘Dear God, thank you …’

His face cracks into a broad smile and he looks completely broken, and he stares up at the falling snow as his legs give way beneath him. The policewoman tries to catch him, but one of his knees hits the ground and he falls to the side, putting his hand out to break his fall.

The police officer helps him to his feet, and he is holding her arm as he sees Veronica come running down the steps barefoot, wrapped in his thick winter coat.

‘You’re sure it’s him?’ he says, staring into the policewoman’s eyes.

She nods.

‘We’ve just had a one hundred per cent match,’ she repeats. ‘It’s Mikael Kohler-Frost, and he’s alive.’

Veronica has reached him. He takes her arm as he follows the policewoman back to the car.

‘What’s going on, Reidar?’ she asks, sounding worried.

He looks at her. His face is confused and he suddenly seems much older.

‘My little boy,’ he says simply.

37

From a distance the white blocks of Södermalm Hospital look like gravestones looming out of the thick snow.

Moving like a sleepwalker, Reidar Frost buttoned his shirt on the way to Stockholm and tucked it into his trousers. He’s heard the police say that the patient who has been identified as Mikael Kohler-Frost has been moved from intensive care to a private room, but it all feels as if it’s happening in a parallel reality.

In Sweden, when there are grounds to believe someone is dead, the relatives can apply for a death certificate after one year even though there is no body. Reidar had waited six years for his children’s bodies to be found before he applied for death certificates. The Tax Office authorised his request, the decision was taken, and the declarations became legally binding six months later.

Now Reidar is walking beside the plain-clothed officer down a long corridor. He doesn’t remember which ward they’re on their way towards, he just follows her, staring at the floor and interwoven tracks left by the wheels of countless beds.

Reidar tries to tell himself not to hope too much, that the police might have made a mistake.

Thirteen years ago his children disappeared, Felicia and Mikael, when they were out playing late one evening.

Divers searched the waters, and the whole of the Lilla Värtan inlet was dragged, from Lindskär to Björndalen. Search parties had been organised and a helicopter spent several days searching the area.

Reidar provided photographs, fingerprints, dental records and DNA samples of both children to assist in the search.

Known offenders were questioned, but the conclusion of the police investigation was that one of the siblings had fallen into the cold March water, and the other had been dragged in while trying to help the first one out.

Reidar secretly commissioned a private detective agency to investigate other possible leads, primarily everyone in the children’s vicinity: all their teachers, football coaches, neighbours, postmen, bus drivers, gardeners, shop assistants, café staff, and anyone the children had come into contact with by phone or on the internet. Their classmates’ parents were checked, and even Reidar’s own relatives.

Long after the police had stopped looking, and when everyone with even the faintest connection to the children had been investigated, Reidar began to realise that it was over. But for several years after that he carried on walking along the shore every day, expecting his children to be washed ashore.

Reidar and the plain-clothes officer with the blonde ponytail down her back wait while a bed containing an old woman is wheeled into the lift. They head over to the doors to the ward and pull on pale blue shoe-covers.

Reidar staggers and leans against the wall. He has wondered several times if he’s dreaming, and daren’t let his thoughts get carried away.

They carry on into the ward, passing nurses in white uniforms. Reidar feels composed, he’s clenched tight inside, but he can’t help walking faster.

Somewhere he can hear the noise of other people, but inside him there is nothing but an immense silence.

At the far end of the corridor, on the right, is room number four. He bumps into a food trolley, sending a pile of cups to the floor.

It’s as if he’s become detached from reality as he enters the room and sees the young man lying in bed. He has a drip attached to the crook of his arm, and oxygen is being fed into his nose. An infusion bag is hanging from the drip-stand, next to a white pulse-monitor attached to his left index finger.

Reidar stops and wipes his mouth with his hand, and feels himself lose control of his face. Reality returns like a deafening torrent of emotions.

‘Mikael,’ Reidar says gently.

The young man slowly opens his eyes and Reidar can see how much he resembles his mother. He carefully puts his hand against Mikael’s cheek, and his own mouth is trembling so much that he can hardly speak.

‘Where have you been?’ Reidar asks, and realises that he’s crying.

‘Dad,’ Mikael whispers.

His face is frighteningly pale and his eyes incredibly tired. Thirteen years have passed, and the child’s face that Reidar has hidden in his memory has become a man’s face, but he’s so skinny that he looks like he did when he was newborn, wrapped in a blanket.

‘Now I can be happy again,’ Reidar whispers, stroking his son’s head.

38

Disa is finally back in Stockholm again. She’s waiting in his flat, on the top floor of number 31 Wallingatan. Joona is on his way home from buying some turbot that he’s planning to fry and serve with remoulade sauce.

Alongside the railings the snow is piled about twenty centimetres deep. All the lights of the city look like misty lanterns.

As he passes Kammakargatan he hears agitated voices up ahead. This is a dark part of the city. Heaps of snow and rows of parked cars throw shadows. Dull buildings, streaked with melt-water.

‘I want my money,’ a man with a gruff voice is shouting.

There are two figures in the distance. They’re moving slowly along the railings towards the Dala steps. Joona carries on walking.

Two panting men are staring at each other, hunched, drunk and angry. One is wearing a chequered coat and a fur hat. In his hand is a small, shiny knife.

‘Fucking bastard,’ he rattles. ‘Fucking little—’