Полная версия:

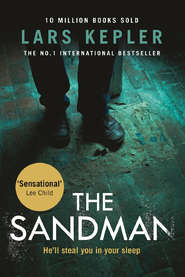

The Sandman

‘Everyone thinks they fell in the water,’ the wife had said, her head starting to shake again.

‘You mentioned that they sometimes climb out of the window after their bedtime prayers,’ Joona went on calmly.

‘Obviously, they’re not supposed to,’ Reidar said.

‘But you know that they sometimes creep out and cycle off to see a friend?’

‘Rikard.’

‘Rikard van Horn, number 7 Björnbärsvägen,’ Joona said.

‘We’ve tried talking to Micke and Felicia about it, but … well, they’re children, and I suppose we didn’t think it was that harmful,’ Reidar replied, gently laying his hand over his wife’s.

‘What do they do at Rikard’s?’

‘They never stay for long, just play a bit of Diablo.’

‘They all do,’ Roseanna whispered, pulling her hand away.

‘But on Saturday they didn’t cycle to Rikard’s, but went to Badholmen instead,’ Joona went on. ‘Do they often go there in the evening?’

‘We don’t think so,’ Roseanna said, getting up restlessly from the table, as if she could no longer keep her internal trembling in check.

Joona nodded.

He knew that the boy, Mikael, had answered the phone just before he and his younger sister had left the house, but the number had been impossible to trace.

It had been unbearable, sitting there opposite the children’s parents. Joona said nothing, but was feeling more and more convinced that the children were victims of the serial killer. He listened, and asked his questions, but he couldn’t tell them what he suspected.

21

If the two children were victims of this serial killer, and they were correct in thinking that he would soon try to kill one of the parents as well, they had to make a choice.

Joona and Samuel decided to concentrate their efforts on Roseanna Kohler.

She had moved out to live with her sister in Gärdet, in north-east Stockholm.

The sister lived with her four-year-old daughter in a white apartment block at 25 Lanforsvägen, close to Lill-Jan’s Forest.

Joona and Samuel took turns keeping watch on the building at night. For a week, one of them would sit in their car a bit further along the road until it got light.

On the eighth day Joona was leaning back in his seat, watching the building’s inhabitants get ready for night as usual. The lights went off in a pattern that he was starting to recognise.

A woman in a silver-coloured padded jacket went for her usual walk with her golden retriever, then the last windows went dark.

Joona’s car was parked in the shadows on Porjusvägen, between a dirty white pickup and a red Toyota.

In the rear-view mirror he could see snow-covered bushes and a tall fence surrounding an electricity substation.

The residential area in front of him was completely quiet. Through the windscreen he watched the static glow of the streetlamps, the pavements and unlit windows of the buildings.

He suddenly started to smile to himself when he thought about the dinner he had eaten with his wife and little daughter before he drove out there. Lumi had been in a hurry to finish so she could carry on examining Joona.

‘I’d like to finish eating first,’ he suggested.

But Lumi had adopted her serious expression and talked to her mother over his head, asking if he was brushing his teeth himself yet.

‘He’s very good,’ Summa replied.

She explained with a smile that all of Joona’s teeth had come through, as she carried on eating. Lumi put a piece of kitchen roll under his chin and tried to stick a finger in his mouth, telling him to open wide.

His thoughts of Lumi vanished as a light suddenly went on in the sister’s flat. Joona saw Roseanna standing there in a flannel nightdress, talking on the phone.

The light went out again.

An hour passed, but the area remained deserted.

It was starting to get cold inside the car when Joona caught sight of a figure in the rear-view mirror. Someone hunched over, approaching down the empty street.

22

Joona slumped down slightly in his seat and followed the figure’s progress in the rear-view mirror, trying to catch a glimpse of its face.

The branches of a rowan tree swayed as he passed.

In the grey lights from the substation Joona saw that it was Samuel.

His colleague was almost half an hour early.

He opened the car door and sat down in the passenger seat, pushed the seat back, stretched out his legs and sighed.

‘OK, so you’re tall and blond, Joona … and it’s really lovely being in the car and everything. But I still think I’d rather spend the night with Rebecka … I want to help the boys with their homework.’

‘You can help me with my homework,’ Joona said.

‘Thanks,’ Samuel laughed.

Joona looked out at the road, at the building with its closed doors, the rusting balconies, the windows that shone blackly.

‘We’ll give it three more days,’ he said.

Samuel pulled out the silver-coloured flask of yoich, as he called his chicken soup.

‘I don’t know, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking,’ he said seriously. ‘Nothing about this case makes sense … we’re trying to find a serial killer who may not actually exist.’

‘He exists,’ Joona replied stubbornly.

‘But he doesn’t fit with what we’ve found out, he doesn’t fit with any aspect of the investigation, and—’

‘That’s why … that’s why no one has seen him,’ Joona said. ‘He’s only visible because he casts a shadow over the statistics.’

They sat beside each other in silence. Samuel blew on his soup, and beads of sweat broke out on his forehead. Joona hummed a tango and let his eyes wander from Roseanna’s bedroom window to the icicles hanging from the guttering, then up at the snow-covered chimneys and vents.

‘There’s someone behind the building,’ Samuel suddenly whispered. ‘I’m sure I saw movement.’

Samuel pointed, but everything was in a state of dreamlike peace.

A moment later Joona saw some snow fall from a bush close to the house. Someone had just brushed past it.

Carefully they opened the car doors and crept out.

The sleepy residential area was quiet. All they could hear were their own footsteps and the electric hum from the substation.

There had been a thaw for a couple of weeks, then it had started to snow again.

They approached the windowless gable-end of the building, walking quietly along the strip of grass, past a wallpaper shop on the ground floor.

The glow from the nearest streetlamp reached out across the smooth snow to the open space behind the houses. They stopped at the corner, hunched over, trying to check the trees as they got denser towards the Royal Tennis Club and Lill-Jan’s Forest.

At first Joona couldn’t see anything in the darkness between the crooked old trees.

He was about to give Samuel the signal to proceed when he saw the figure.

There was a man standing among the trees. He was as still as the snow-covered branches.

Joona’s heart began to beat faster.

The slim man was staring like a ghost up at the window where Roseanna Kohler was sleeping.

The man showed no sign of urgency, had no obvious purpose.

Joona was filled with an icy conviction that the man in the garden was the serial killer whose existence they had speculated about.

The shadowy figure was thin and crumpled.

He was just standing there, as if the sight of the house gave him a sense of calm satisfaction, as if he already had his victim in a trap.

They drew their weapons, but were unsure of what to do. They hadn’t discussed this in advance. Even though they had been keeping watch on Roseanna for days, they had never talked about what they would do if it transpired that they were right.

They couldn’t just rush over and arrest a man who was simply standing there looking at a dark window. They may find out who he was, but they might well be forced to release him.

23

Joona stared at the motionless figure between the tree trunks. He could feel the weight of his semi-automatic pistol and the chill of the night air on his fingers. He could hear Samuel’s breathing beside him.

The situation was beginning to seem slightly absurd when, without warning, the man took a step forward.

They could see he was holding a bag in one hand.

Afterwards it was hard to know what it was that convinced them both that they had found the man they were looking for.

The man just smiled up at the window of Roseanna’s bedroom, then vanished into the bushes.

The snow covering the grass crunched faintly beneath their feet as they crept after him. They followed the fresh footprints through the dormant forest until they eventually reached an old railway line.

Far off to the right they could see the figure on the track. He passed below an electricity pylon, crossing the tangle of shadows thrown by its frame.

The railway was still used for goods traffic, and ran from Värta Harbour right through Lill-Jan’s Forest.

Joona and Samuel followed, sticking to the deep snow beside the tracks to avoid being seen.

The railway line carried on beneath a viaduct and into the expanse of forest. Suddenly everything got much quieter and darker again.

The black trees stood close together with their snow-covered branches.

Joona and Samuel silently speeded up so as not to lose sight of him.

When they emerged from the curve around Uggleviken marsh they could see that the railway line stretching out ahead of them was empty.

The man had left the track somewhere and gone into the forest.

They climbed up onto the rails and looked out into the white forest, then started to walk back. It had been snowing over recent days and the snow was largely untouched.

Then they found a set of footprints they had missed earlier. The skinny man had left the rails and headed off into the forest. The ground beneath the snow was wet and the prints left by his shoes had darkened. Ten minutes before they had been white and impossible to see in the weak light, but now they were dark as lead.

They followed the tracks into the forest, towards the large reservoir. It was almost pitch-black among the trees.

The murderer’s footprints were crossed three times by the lighter tracks of a hare.

At one point it was so dark that they lost his trail again. They stopped, then spotted the tracks again and hurried on.

Suddenly they could hear high-pitched whimpering sounds. It was like an animal crying, like nothing Joona and Samuel had ever heard before. They followed the footprints and drew closer to the source of the sounds.

What they saw between the tree trunks was like something out of some grotesque medieval story. The man they had followed was standing in front of a shallow grave. The ground around him was covered with freshly dug earth. An emaciated, filthy woman was trying to get out of the coffin, crying and struggling to clamber up over the edge. But each time she was on her way up, the man pushed her down again.

For a couple of seconds Joona and Samuel could only stand there, staring, before taking the safety catches off their weapons and rushing in.

The man wasn’t armed, and Joona knew he ought to aim at the man’s legs, but he couldn’t help aiming at his heart.

They ran over the dirty snow, forced the man onto his stomach and cuffed both his wrists and feet.

Samuel stood panting, pointing his pistol at the man as he called emergency control.

Joona could hear the sob in his voice.

They had caught a previously unknown serial killer.

His name was Jurek Walter.

Joona carefully helped the woman up out of the coffin, and tried to calm her down. She just lay on the ground gasping. When Joona explained that help was on the way, he caught a glimpse of movement through the trees. Something large was running away, a branch snapped, fir trees swayed and snow fell softly like cloth.

Perhaps it was a deer.

Joona realised later that it must have been Jurek Walter’s accomplice, but right then all they could think about was saving the woman and getting the man into custody in Kronoberg.

It turned out that the woman had been in the coffin for almost two years. Jurek Walter had regularly supplied her with food and water, then covered the grave over again.

The woman had gone blind, and was severely undernourished, her muscles had atrophied and compression sores had left her deformed, and her hands and feet had suffered frostbite.

At first it was assumed that she was merely traumatised, but as time passed it became clear that she had incurred severe brain damage.

24

Joona locked the door very carefully when he got home at half past four that morning. His heart thudding with trepidation, he moved Lumi’s warm, sweaty body closer to the middle of the bed before putting his arm round both her and Summa. He realised he wasn’t going to be able to sleep, but just needed to lie down with his family.

He was back in Lill-Jan’s Forest by seven o’clock. The area had been cordoned off and was under guard, but the snow around the grave was already so churned up by the police, dogs and paramedics that there was no point trying to find any tracks of a potential accomplice.

Before ten o’clock a police dog unit had identified a location close to the Uggleviken reservoir, just two hundred metres from the woman’s grave. A team of forensics experts and crime-scene analysts was called in, and a couple of hours later the remains of a middle-aged man and a boy of about fifteen had been exhumed. They were both squashed into a blue plastic barrel, and forensic examination indicated that they’d been buried almost four years before. They hadn’t survived many hours in the barrel even though there was a tube supplying them with air.

Jurek Walter was registered as living on Björnövägen, part of a large housing estate built in the early 1970s, in the Hovsjö district of Södertälje. It was the only address in his name. According to the records, he hadn’t lived anywhere else since he arrived in Sweden from Poland in 1994 and was granted a work permit.

He had taken a job as a mechanic for a small company, Menge’s Engineering Workshop, where he repaired train gearboxes and renovated diesel engines.

All the evidence suggested that he lived a lonely, peaceful life.

Joona and Samuel and the two forensics officers didn’t know what they might find in Jurek Walter’s flat. A torture chamber or trophy cabinet, jars of formaldehyde, freezers containing body parts, shelves bulging with photographic documentation?

The police had cordoned off the immediate vicinity of the block of flats, and the whole of the second floor.

They put on protective clothing, opened the door and started to set out boards to walk on, so that they wouldn’t ruin any evidence.

Jurek Walter lived in a two-room flat measuring thirty-three square metres.

There was a pile of junk mail below the letterbox. The hall was completely empty. There were no shoes or clothes in the wardrobe beside the front door.

They moved further in.

Joona was prepared for someone to be hiding inside, but everything was perfectly still, as if time had abandoned the place.

The blinds were drawn. The flat smelled of sunshine and dust.

There was no furniture in the kitchen. The fridge was open and switched off. There was nothing to suggest it had ever been used. The hotplates on the cooker had rusted slightly. Inside the oven the operating instructions were still taped to the side. The only food they found in the cupboards was two tins of sliced pineapple.

In the bedroom was a narrow bed with no bedclothes, and inside the wardrobe one clean shirt hung from a metal hanger.

That was all.

Joona tried to work out what the empty flat signified. It was obvious that Jurek Walter didn’t live there.

Perhaps he only used it as a postal address.

There was nothing in the flat to lead them anywhere else. The only fingerprints belonged to Jurek himself.

He had no criminal record, had never been suspected of any crime, he wasn’t on any registers held by social services. Jurek Walter had no private insurance, had never taken out a loan, his tax was deducted directly from his wages, and he had never claimed any tax credits.

There were so many different registers. More than three hundred of them, all covered by the Personal Records Act. Jurek Walter was only listed in the ones that no citizen could avoid.

Otherwise he was invisible.

He had never been off sick, had never sought help from a doctor or dentist.

He wasn’t in the firearms register, the vehicle register, there were no school records, no registered political or religious affiliations.

It was as if he had lived his life with the express intention of being as invisible as possible.

There was nothing that could lead them any further.

The few people he had been in contact with at his workplace knew nothing about him. They could only report that he never said much, but he was a very good mechanic.

When the National Criminal Investigation Department received a response from the Policja, their Polish counterparts, it turned out that Jurek Walter had been dead for many years. Because this Jurek Walter had been found murdered in a public toilet at the central station, Kraków Główny, they were able to supply both photographs and fingerprints.

Neither pictures nor prints matched the Swedish serial killer.

Presumably he had stolen the identity of the real Jurek Walter.

The man they had captured in Lill-Jan’s Forest was looking more and more like a frightening enigma.

They went on combing the forest for another three months, but after the man and boy in the barrel no more of Jurek Walter’s victims had been found.

Not until Mikael Kohler-Frost turned up, walking across a bridge, heading for Stockholm.

25

A prosecutor took over responsibility for the preliminary investigation, but Joona and Samuel led the interviews, from the custody proceedings to the principal interrogation. Jurek Walter didn’t confess to anything, but he didn’t deny any crimes either. Instead he philosophised about death and the human condition. Because of the relative lack of supporting evidence, it was the circumstances surrounding his arrest, his failure to offer an explanation and the forensic psychiatrist’s evaluation that led to his conviction in Stockholm Courthouse. His lawyer appealed against the conviction and while they were waiting for the case to be heard in the Court of Appeal, more interviews were held in Kronoberg Prison.

The staff at the prison were used to most things, but Jurek Walter’s presence troubled them. He made them feel uneasy. Wherever he was, conflicts would suddenly flare up; on one occasion two warders started fighting, with one of them ending up in hospital.

A crisis meeting was held, and new security procedures agreed. Jurek Walter would no longer be allowed to come into contact with other inmates, or use the exercise yard.

When Samuel called in sick, Joona found himself walking alone down the corridor, past the row of white thermos flasks, one outside each of the green doors. The shiny linoleum floor had long, black marks on it.

The door to Jurek Walter’s cell was open. The walls were bare and the window barred. The morning light reflected off the worn plastic-covered mattress on the fixed bunk and the stainless-steel basin.

Further along the corridor a policeman in a dark-blue sweater was talking to a Syrian Orthodox priest.

‘They’ve taken him to interview room two,’ the officer called to Joona.

A guard was waiting outside the interview room, and through the window Joona could see Jurek Walter sitting on a chair, looking down at the floor. In front of him stood his legal representative and two guards.

‘I’m here to listen,’ Joona said when he went in.

There was a short silence, then Jurek Walter exchanged a few words with his lawyer. He spoke in a low voice and didn’t look up as he asked the lawyer to leave.

‘You can wait in the corridor,’ Joona told the guards.

When he was on his own with Jurek Walter in the interview room he moved a chair and put it so close that he could smell the man’s sweat.

Jurek Walter sat still on his chair, his head drooping forward.

‘Your defence lawyer claims that you were in Lill-Jan’s Forest to free the woman,’ Joona said in a neutral voice.

Jurek went on staring at the floor for another couple of minutes, then, without the slightest movement, said:

‘I talk too much.’

‘The truth will do,’ Joona said.

‘But it really doesn’t matter to me if I’m found guilty of something I didn’t do,’ Walter said.

‘You’ll be locked up.’

Jurek looked up at Joona and said thoughtfully:

‘The life went out of me a long time ago. I’m not scared of anything. Not pain … not loneliness or boredom.’

‘But I’m looking for the truth,’ Joona said, intentionally naïve.

‘You don’t have to look for it. It’s the same with justice, or gods. You make a choice to fit your own requirements.’

‘But you don’t choose the lies,’ Joona said.

Jurek’s pupils contracted.

‘In the Court of Appeal the prosecutor’s description of my actions will be regarded as proven beyond all reasonable doubt,’ he said, without the slightest hint of a plea in his voice.

‘You’re saying that’s wrong?’

‘I’m not going to get hung up on technicalities, because there isn’t really any difference between digging a grave and refilling it.’

When Joona left the interview room that day, he was more convinced than ever that Jurek Walter was an extremely dangerous man, but at the same time he couldn’t stop thinking about the possibility that Jurek had been trying to say that he was being punished for someone else’s crimes. Of course he understood that it had been Jurek Walter’s intention to sow a seed of doubt, but he couldn’t ignore the fact that there was actually a flaw in the prosecution’s case.

26

The day before the appeal, Joona, Summa and Lumi went to dinner with Samuel and his family. The sun had been shining through the linen curtains when they started eating, but it was now evening. Rebecka lit a candle on the table and blew out the match. The light quivered over her luminous eyes, and her one strange pupil. She had once explained that it was a condition called dyscoria, and that it wasn’t a problem, she could see just as well with that eye as the other.

The relaxed meal concluded with dark honey cake. Joona borrowed a kippah for the prayer, Birkat Hamazon.

That was the last time he saw Samuel’s family.

The boys played quietly for a while with little Lumi before Joshua immersed himself in a video game and Reuben disappeared into his room to practise his clarinet.

Rebecka went outside for a cigarette, and Summa kept her company with her glass of wine.

Joona and Samuel cleared the table, and as soon as they were alone started talking about work and the following day’s appeal.

‘I’m not going to be there,’ Samuel said seriously. ‘I don’t know, it’s not that I’m frightened, but it feels like my soul gets dirty … that it gets dirtier for every second I spend in his vicinity.’