Полная версия:

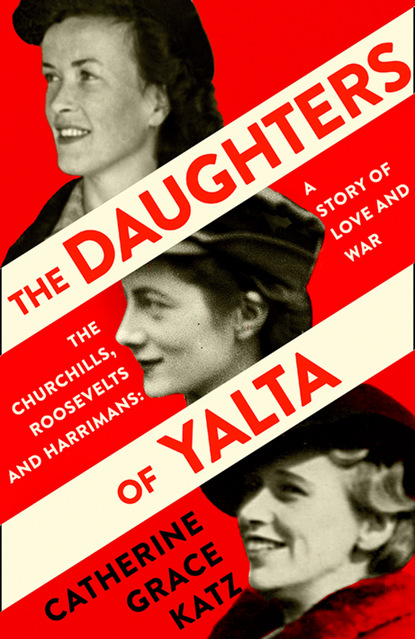

The Daughters of Yalta

But more than that, the deep connection between father and daughter confirmed the rightness of the decision. Since childhood, Sarah had felt like something of a ‘loner’. Nervous and shy, she formed few friendships with the other girls in her social circle. As a teenager she spent much of her debutante season hiding in the bathroom, playing cards with her cousin Unity Mitford, to avoid making small talk with her peers. Even at home, from the time she was a little girl, she had felt timid and awkward in her father’s presence. Whenever she worked up the nerve to speak to him, she had been sure to ‘tidy’ her mind before she opened her mouth. If her message was important, she would instead write her thoughts in a note. Though she always felt her father was much more eloquent and quick-witted than she was, she did believe that she understood him and, even in her silence, that he understood her. Others in the family would tease her for her reticence, but he would stay their tongues in an instant, saying, ‘Sarah is an oyster, she will not tell us her secrets.’

During the quiet hours spent laying bricks at her father’s side, Sarah studied him as a naturalist studies a species. She observed that when he was ‘with a trusted audience he would let them see his mind leaping and ranging around a problem in a breathlessly spectacular way.’ Sarah desperately wanted to be part of this trusted audience, to be ‘in the league of people, who if they could not help, understood where he was trying to go with an idea’. So she decided to ‘train [her]self to think; not the things he thought, but the way he thought, and would apply it to certain problems as a practice’. Even if she did not speak, she wanted him to know that she was ‘in silent step with him’. Now perhaps no one, aside from her mother, knew Winston Churchill’s mind better than Sarah.

It was for this reason that Sarah now found herself in Malta, watching her father as he impatiently paced the deck. Other than his protégé, Anthony Eden, there was no one else within the British delegation to whom he could confess his deep concerns about the upcoming conference, particularly his frustration with his American ally. But even Eden had his own agenda and political future to look after. Winston needed someone at his side who could share his inner burden while asking only to be allowed to help. Someone who could temper the linguistic torrent he unleashed behind closed doors, but one who could also interpret his feelings in the words left unsaid. At home, this task fell to Clementine, who had carefully honed her ability to channel her husband’s energy and prod his impassioned speech and deepest convictions in a positive direction. Sarah did not have her mother’s forty years of experience managing Winston Churchill, but she had experience enough. Just as she had maintained the plumb line on the brick walls at Chartwell, she could maintain the plumb line here, and help him adjust course when emotion tempted him off the narrow path he had to walk between his partners in the tripartite alliance.

At 9.35 a.m. the president’s ship, the USS Quincy, finally appeared on the horizon. Ever so slowly, it eased its way into the harbour, carefully avoiding the submarine nets at the entrance. A squadron of six Spitfires raced across the sky, and the bands amassed on shore sprang to life, greeting the cruiser with a soaring rendition of the U.S. national anthem, followed by a rousing round of ‘God Save the King’. With the aid of a tugboat, the thirteen-thousand-ton warship inched towards its berth. The two ships were so close together in the narrow inlet that Sarah could see the face of every person on the Quincy as it passed. The ship’s crew was splendidly turned out at attention on deck. Sarah had to admit, the American sailors, soldiers and airmen looked to be ‘very superior creatures’. The prime minister had stopped pacing and positioned himself on the landing, at the top of one of his ship’s ladders facing the water. He had promised Roosevelt he would be ‘waiting on the quay’ when the president arrived. This would do just as well.

As the Quincy drew even with the Orion, a hush suddenly fell over the crowd. There, on the ship’s bridge, was the president of the United States, sitting with a dignified posture in his wheelchair, along the rail. The president and the prime minister regarded each other. Churchill, standing firmly at attention, slowly raised his hand to his cap. Each man gave the other a firm salute. Just for an instant, the past few months’ tension and pent-up frustration melted away as the two old friends were reunited. Even to Sarah, who had spent a lifetime surrounded by dignitaries and statesmen, it was a ‘thrilling sight’. Across the harbour, on the Sirius, the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, was standing with the American delegates Harriman, Hopkins and Stettinius, observing the encounter. It was a moment, Eden later professed, when the world ‘seem[ed] to stand still’, making one ‘conscious of a mark in history’.

Finally, the Quincy docked in its berth and lowered its gangplank. Harriman, Stettinius, Hopkins and General Marshall boarded first to greet their boss. Shortly thereafter, a formal announcement was made and the prime minister was ‘piped aboard’. Sarah soon followed. Arriving on deck, she was ushered to a group of four wicker chairs arranged in the sunlight, where her father and the president sat side by side. They made an incongruous pair. With his Royal Yacht Squadron uniform, Churchill appeared dressed for a military parade, while Roosevelt was attired simply in a dark, striped suit and a tweed flat cap, as if he could not decide whether he was ready for a business meeting in the city or a country picnic at his beloved Hill-Top Cottage in Hyde Park, New York.

Like Churchill, Roosevelt had not come to Malta alone. Given his physical limitations, he often travelled with one or more of his sons, who helped him to stand and move between his chair, his car and his bed. At Tehran, both his son Elliott and his son-in-law John Boettiger had accompanied him, but this time he had left them at home. In early January, Roosevelt had cabled Churchill with an unexpected message: ‘If you are taking any of your personal family to ARGONAUT, I am thinking of including my daughter Anna in my party.’ FDR had never brought Anna, the oldest of his five children and his only daughter, on an official trip abroad before. It was a surprising, albeit welcome change to his retinue. ‘How splendid,’ Churchill replied. ‘Sarah is coming with me.’

Winston and Clementine had met the ‘first daughter’ during their visit to Washington in 1943, and Sarah had spent time with Anna’s husband, John Boettiger, at Tehran, but simply by reading the newspapers Sarah would have learned about Anna. The president’s daughter was thirty-eight and had three children: a teenage daughter and son from her first marriage, to a stockbroker named Curtis Dall, and a five-year-old son with John. Before John had joined the army in 1943 as a captain in the Civilian Affairs Division, Anna and John had lived in Seattle, where they edited a newspaper, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. With her husband deployed to North Africa and the Mediterranean, Anna had moved from Seattle to the White House in early 1944. After years of relative obscurity out west, she had become an increasingly visible figure in Washington; she frequently stood in for her mother as surrogate First Lady during Eleanor Roosevelt’s numerous trips.

Now, here Anna was, sitting across from FDR. The two daughters were introduced. Anna was tall and blonde; her fine, straight hair, set in a permanent wave, had become frizzy in the sea air. Like her father, she wore a simple civilian suit and hat. Immediately Sarah was struck by just how much Anna looked like Eleanor. ‘Although,’ Sarah noted conspiratorially in a letter to her own mother, Anna was ‘so much better looking’. Then another amusing thought occurred to her. She supposed strangers thought she and her older sister, Diana, looked much like Clementine, except in that case, ‘not so good looking!’ Appearances aside, Anna seemed an easygoing, pleasant person. Sarah decided she liked her very much. However, she observed that in spite of Anna’s casual manner, she seemed to be ‘quite nervous about being on the trip’.

Settling in, Sarah turned her attention to the president, who was seated to her left. Winston’s frustration with Roosevelt aside, Sarah was glad to see him again. At Tehran, she had found him a warm and charming man. He was so full of life that at times he seemed ready to leap out of his chair, as if he had forgotten he could not walk. Looking at him now, Sarah was taken aback. This vitality so evident at Tehran was gone, the life sapped from his slackened face. It seemed he had aged a ‘million years’ over the fourteen months since she had last seen him, and his conversation, once sparkling and witty, wandered and meandered.

Something had definitely changed. Even the president’s ever-present group of friends and advisers had notably altered. From what Sarah observed on board the ship that morning and learned during conversations with the Americans who had arrived the day before, Harry Hopkins, once inseparable from Roosevelt, no longer held the position of influence he had long enjoyed. Poor Hopkins had been seriously ill for some time. He had been treated at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota for the side effects of stomach cancer, which he had been battling for the past six years. Hopkins had willed himself to make it to this conference, but an unfamiliar distance had arisen between him and the president. In place of Hopkins, Edward Stettinius, who had been secretary of state for only two months, had become Roosevelt’s primary ‘buddy’. Perhaps Sarah was wrong, but based on her first interactions with him, Stettinius had seemed rather ‘wooden headed’. Worst of all, John Gilbert Winant, the American ambassador to Britain, was thousands of miles away. Although all the other American, British and Soviet ambassadors had been included (with the exception of Lord Halifax, Churchill’s envoy to the United States, who had remained in Washington and had not attended previous international wartime conferences), Roosevelt had left Winant in London. Sarah desperately wished Winant, or Gil, as she knew him, was there. This was not just a selfish wish. When Winant was present, Sarah knew her father had a strong, true friend among the Americans. But with Winant in London and Hopkins in a diminished role, the president’s inner circle at Yalta would be distinctly less pro-British.

The joy Sarah had felt as she watched her father and Roosevelt salute each other passed quickly as Winston’s anxiety about the state of the relationship between Britain and the United States crept into her mind. What had happened to Roosevelt since she had seen him in Tehran? ‘Is it health,’ she wondered, ‘or has he moved away a little from us?’

THREE

February 2, 1945

Perhaps it was because Sarah had an actor’s ability to summon a wide range of emotions or simply because she had a natural ability to read people. Within moments of sitting down across from the Roosevelts on the Quincy, Sarah sensed what Anna was desperately trying to hide. Anna was indeed nervous about the trip, but not because she was new to the world of tripartite conferences, nor because she was, for the first time, seeing firsthand the furious destruction left by war. Anna was anxious not for herself but for her father. Sarah’s perception had been acute: Franklin Roosevelt was seriously ill. He was dying of congestive heart failure. Other than the doctors, Anna was the only person who knew just how grave the situation had become.

In the winter of 1944, after her husband joined the army, Anna had moved back to the White House, with her four-year-old son. Shortly after her arrival, she began to notice small changes in her father. He had a persistent cough, his skin looked ashen, and he appeared far more exhausted than a man of sixty-two years should be. Granted, twelve years in the White House, including two at war, would have taken a toll on the fittest man in his prime, but this condition hinted at something more than fatigue. The signs were perceptible to only the most attentive observers. His hands shook when he lit a cigarette. Once, while writing his name at the end of a letter, he seemed to draw a blank, dragging the pen across the page in an unintelligible black squiggle. Sometimes in the dark of the White House movie theatre, as the family watched an after-dinner film, the light coming from the screen would be just bright enough for Anna to glimpse her father’s mouth hanging open for long stretches of time, as if he could not muster the energy to keep it closed.

Anna’s mother, Eleanor, attributed much of FDR’s increased fatigue to concerns about their troublesome middle son, Elliott. He had recently announced that he was divorcing his second wife, Ruth, in order to marry a film starlet. But Anna’s observations, taken together with a remark by FDR’s secretary, Grace Tully, that he had either fallen asleep or briefly lost consciousness while signing papers some months earlier, compelled Anna to take action. She summoned her father’s doctor, Vice Admiral Ross McIntire, an ear, nose and throat specialist. He tried to tell her that The president was simply suffering the prolonged effects of earlier bouts of influenza, sinus infection and fever, but Anna was unconvinced. She insisted that FDR have a comprehensive medical evaluation.

A thorough examination by the young cardiologist Howard Bruenn, at Bethesda Naval Hospital in late March 1944, revealed that Anna’s suspicions had been correct. The president was breathless after moderate exertion, there was fluid in his lungs, and his blood pressure was 186/108 mmHg – a systolic number indicating a hypertensive crisis. Cardiology was a relatively new field – a professional organisation of American cardiologists had convened for the first time in 1934 – but to Bruenn, the results were clear: the president was suffering from acute congestive heart failure, a disease for which there was no cure. Bruenn could try to prolong his patient’s life by using digitalis to temporarily clear the fluid in his lungs and by advising him to shorten his work hours, sleep more, maintain a strict diet, and lose weight to reduce the strain on the heart. But it was just a waiting game. Treating heart failure was beyond McIntire’s capabilities, so he begrudgingly agreed to have the thirty-eight-year-old Bruenn take over the president’s primary care on one important condition: Bruenn was not to tell anyone about FDR’s diagnosis – no one in the Roosevelt family, and especially not the president himself. Surprisingly, Bruenn faced no resistance from the patient. FDR never asked what was wrong with him.

But Anna was no fool. There had to be a reason why her father was taking new medications, why his diet now closely resembled that of her toddler, and why the new doctor insisted FDR work no more than four hours a day. Before long, Bruenn broke McIntire’s rule and took Anna into his confidence, revealing FDR’s diagnosis in enough detail to ensure that his recommendations were given serious attention. Anna read whatever she could about heart disease and followed Bruenn’s instructions to the letter. Aside from her husband, she told no one, not even her mother.

Though Roosevelt asked Bruenn no details about his health, he must have sensed that something was seriously wrong and that Anna was protecting him. Her presence at Yalta represented an abrupt change from the situation at Tehran. Then, Anna had begged to accompany her father, but he had flatly refused, for no logical reason. Instead he chose her brother Elliott and her husband, John. This rejection had stung Anna. Yes, her brother and husband could help support Roosevelt physically in a way she could not, but his Secret Service officer, Mike Reilly, could have done that. Not only had Elliott accompanied FDR to Tehran, but both Elliott and Anna’s younger brother Franklin Jr had joined their father at the Atlantic Charter Conference with Churchill in August 1941, at which they had outlined the common principles that united the free world, as well as the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, which solidified the Allies’ commitment to a German unconditional surrender. It was only fair that she should at last have a turn. At the time, Anna had also been desperate to see her husband, whose letters from his posting in Italy had taken on an anxious, depressed tone. She needed to see him to give him some reassurance. As she told FDR, if it was a problem that she was not in uniform, she could join the Red Cross. Still, her father refused to budge: in keeping with the age-old maritime superstition that women on board ships brought bad luck, no women were permitted to sail on navy vessels. (Never mind that, as the commander in chief, Roosevelt easily could have granted her an exception. Or she could have flown.) That old superstition did not seem to bother Winston Churchill, who was bringing Sarah to Tehran. No matter what argument Anna made, FDR would not acquiesce. In a rare fit of frustration with her father, Anna fumed to her mother that FDR was a ‘stinker in his treatment of the female members of his family’. She blazed with anger at the injustice: ‘Pa seems to take for granted that all females should be quite content to “keep the home fires burning,” and that their efforts outside of this are merely amusing and to be aided by a patronising male world only as a last resort to keep some individually troublesome female momentarily appeased.’

But when she approached her father about joining him at Yalta, he simply responded, ‘Well, we’ll just see about that.’ She expected to be disappointed once again. Then, in early January, he surprised her. Winston was bringing Sarah again, and Ambassador Harriman was bringing his daughter, Kathleen. Anna could come along if she wished.

When FDR told Eleanor he had decided to bring Anna, it was her turn to feel hurt. She had commiserated with Anna about being left behind for Tehran, and Anna knew how much Eleanor was hoping Franklin would ask her to join him for this conference. Instead, he put Eleanor off, saying it would be ‘simpler’ if he took Anna, as Churchill and Harriman were bringing their daughters rather than their wives. If Eleanor went, people would feel they had to go out of their way to make a ‘fuss’. Eleanor pretended to understand.

While bringing Anna as his aide-de-camp did indeed simplify logistics, it did not fully explain the larger reason why FDR wanted to bring his daughter, rather than his wife, to this conference. Eleanor either could not see or could not accept that her husband of forty years was truly sick. Meanwhile, for all her good intentions, she did not help alleviate Franklin’s exhaustion – she added to it. Anna admired her mother’s relentless energy – she poured her heart and soul into causes such as advocating for the rights of women and providing opportunities for the poor. Yet she had never been a naturally warm and nurturing person. Anna had clear childhood memories of entering her mother’s room while she was working. Without lifting her head from her papers, Eleanor would say, in a deep, chilling voice, ‘What do you want, dear.’ She did not phrase it as a question. Eleanor lacked a sense of timing as to the propitious time or place to voice her opinions on Franklin’s policy decisions. And her opinions tended to be strong. Though he valued her perspective – in fact, he considered it one of his great assets – she often failed to appreciate the many competing demands on the president’s time, particularly during a time of war. His moments of rest were few and far between. During those precious intervals, he was not especially receptive to being subjected to a family member’s interrogation. At one particular dinner party, Eleanor began quizzing him about some decision or other that he had made. After a trying day, he had been looking forward to a relaxed, sociable evening and did not appreciate Eleanor’s probing questions. Noticing that he was about to reach boiling point, Anna jumped in as mediator, lightheartedly heading Eleanor off by saying, ‘Mother, can’t you see you are giving Father indigestion?’ In his public and private life, FDR was constantly surrounded by a crush of people clamouring for his favour and attention. Anna thought he liked to keep people around him all the time because as a boy, he had grown up with no neighbourhood children to play with and only a much older half brother for occasional company; thus, he always wanted to be ‘one of the gang’. But even if he did not like to admit it, FDR’s energy was not what it once was. It would have been a kind gesture to bring Eleanor to Yalta, but could he be blamed for trying to ensure that a gruelling trip would be as peaceful as possible?

Anna knew how much her father’s decision had wounded Eleanor. In part Anna felt guilty, as if she were betraying her mother – and not for the first time. But Anna also knew that if Eleanor went, she would have to stay at home. So Anna kept her mouth shut, convinced herself that her presence really would keep things ‘simpler’, and blocked the guilt from her mind.

There was another, more nuanced reason why FDR wanted Anna to come with him. She might not have appreciated this rationale, had she allowed herself to consider it for a moment; instead, she breezed past it, another difficulty swept from her thoughts. FDR was able to thoroughly relax in Anna’s presence because he felt that, as a woman, she had ‘no ax to grind’. Unlike her brothers, who could and did use their time with FDR as an opportunity to meet people who might advance their careers, FDR assumed Anna would not be ‘with him because she was inclined … to meet a lot of people to help her get into something else later on’. She existed to serve her family, especially the men, and to keep them tranquil and content.

No matter how hard Anna and Dr Bruenn worked to extend FDR’s life, he would soon die. Going to Yalta was almost certainly Anna’s first and last chance to experience being needed by her father, to become part of his world, which had long been closed to her. So she accepted his reasons for wanting her at his side and chose to interpret them as an affirmation that finally she was a person of value in his life.

Anna had long wished to be the person her father most wanted by his side. Some of her fondest childhood memories recalled the afternoons when she and Franklin had mounted their horses for long rides through the woods and glens surrounding their home in Hyde Park. As they rode, he would point out trees and birds to teach her about different species; he explained how to farm the land in a way most in keeping with the natural environment. Anna imagined that someday they would manage the Hyde Park estate side by side.

FDR indeed loved the natural world, but he loved politics just as much, if not more. He spent countless hours cloistered behind a heavy wooden door, strategising with his political colleagues, the cigar smoke spilling out from the crack under the closed door into the hall. Desperate for his attention, Anna would write him notes, asking him to please come and say good night. She tried to make the prospect more appealing with the promise of pulling a prank on her brother. To the ‘Hon. F.D. Roosevelt,’ she wrote. ‘Will you please come and say goodnight … I am going up now to put something in James’ bed and you may hear some shreiks [sic] when you come in.’ One evening when FDR was shut in his office with his associates, Anna decided to sneak in and hide. Moments later she began to choke on the cigar smoke that filled the room from floor to ceiling, and her eyes started to burn. She had no choice but to give herself up and retreat, coughing and spluttering in utter humiliation. That air was clearly not intended for little girls.

Once, her father had invited her into his library to help him with some books. Anna trembled with nervous excitement at finally joining him in his sacred enclave. She must have trembled too hard, for the instant he handed her a stack of books, they slipped from her arms and crashed to the floor. Anna felt so completely ashamed, she wished she could melt into the ground. Terrified that her father would be furious, she burst into tears and ran away.