Полная версия:

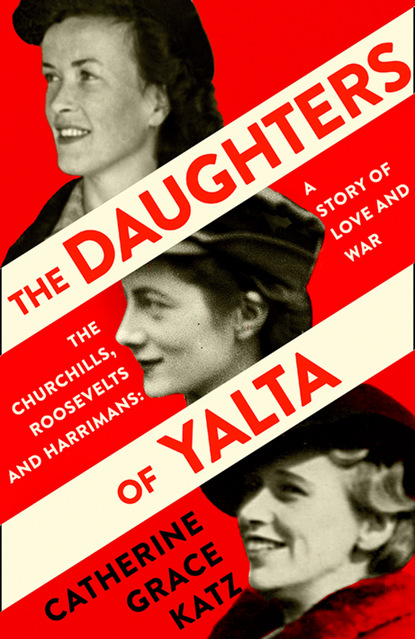

The Daughters of Yalta

Between the planes’ cinematic entrance and the lavish cornucopia the Soviets seemed to conjure out of thin air on the barren steppe, it seemed the delegates had landed on a film set. But as they emerged from their planes, they stepped not into the Technicolor world of Oz, but into Dorothy’s sepia-toned Kansas. Gone were the sun-drenched, rosy limestone buildings and the cerulean waters of Malta. From the concrete tarmac to the snow-covered fields stretching towards the distant, overcast horizon, the land was flat, featureless and colourless. Robert Hopkins, Harry Hopkins’s twenty-two-year-old son and a photographer with the U.S. Army Signal Corps, was travelling with the American delegation as the principal American photographer. He had brought a few precious rolls of colour film, but to use more than one at Saki would have been a waste. The crimson on the three Allied flags, flying from masts along the airfield, presented the only contrast to various tones of grey, which dominated the landscape.

Harriman, Stettinius, Hopkins, Eden and General George Marshall were among the earlier arrivals at ALBATROSS, the code name the Americans irreverently assigned to Saki and its dangerously short runway. The landing strip was just a path of concrete slabs pitted with shell holes, which the Soviets had smoothed as well as they could. The whole thing was covered by a layer of ice. Stettinius remarked that it was like landing on a slippery ‘tile floor’. Miraculously, there had been no mishaps. General Aleksei Antonov of the Red Army had arrived promptly to greet General Marshall. As Marshall stepped off the plane, Antonov invited him to sample the lavish breakfast beneath the tents. Entering the feast-laden pavilion, the humble Pennsylvanian was pleased to find a tumbler full of what looked like fruit juice. Upon closer inspection, Marshall, a teetotaller, discovered that he was wrong. The tumbler was brimming with Crimean brandy. Unflappable as ever, Marshall stepped away from the noxiously sweet digestif. Without a backward glance, he turned to his men and muttered, ‘Let’s get going.’ They departed promptly for Yalta, along with Hopkins, who had become seriously ill during the flight. Stettinius, Eden and Harriman were left to wait in the damp cold for the president and the prime minister. Among them, only Harriman, dressed in a custom-made calf-length leather flight jacket, with fur lining, looked both rakish and at least somewhat prepared for the change in weather. The others had to be content with steaming glasses of sweet Russian tea to stave off the chill seeping through their woollen overcoats.

At ten past noon, the Sacred Cow touched down at Saki and came to a rest on the side of the runway. While FDR readied himself to disembark, Anna hurried off the plane in time to see Churchill’s Skymaster emerge from the clouds. The crowd gathered as the prime minister’s plane taxied to a halt. Soon the door of the fuselage opened and Churchill emerged, dressed in a military greatcoat and an officer’s cap, with a mischievous smile on his face and an eight-inch cigar clenched between his teeth. He gave the assembled crowd a little salute before carefully waddling down the stairs. Sarah followed moments later and joined Anna off to the side. Sarah was once again in uniform and no worse for wear after the overnight flight, while Anna seemed to be getting into the Russian spirit, having changed out of her simple tweed coat into a fur. The Soviet minister of foreign affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov, had been waiting for the distinguished visitors and now greeted the prime minister. The puglike Molotov was dressed all in black, from his double-breasted overcoat to his ushanka, a traditional Russian fur cap with the earflaps tied on top, which accentuated what Churchill described as Molotov’s ‘cannon-ball head’. Surely Molotov, who as a young Bolshevik had chosen that moniker, which meant ‘hammer’, would not have appreciated the teasing. Churchill knew that despite the amusing headwear, the Soviet foreign minister was ruthless and calculating, with his penetrating eyes and a ‘smile of Siberian winter’. Shaking hands with Churchill, Molotov explained through his interpreter, the sallow, shrewish Vladimir Pavlov, that Stalin had not yet arrived in the Crimea. In the meantime, Molotov would be representing the general secretary.

Together, Churchill and Molotov stood waiting for Roosevelt to emerge from the Sacred Cow. Normally, FDR was carried down the steps of an aircraft, but the Sacred Cow’s engineers had installed an elevator that lowered him and his wheelchair from the belly of the fuselage to the ground. There, an open Jeep, one of the thousands of American vehicles that Harriman had negotiated to send to the USSR under Lend-Lease, was waiting. The Soviets had thoughtfully retrofitted it, so that the seat put Roosevelt at the same height as those walking alongside him. Everyone, from Churchill and Molotov to the Red Army soldiers, looked on as Mike Reilly hoisted FDR out of his chair and into the Jeep. It was one of those rare moments when Roosevelt, always so protective of his public image, had no choice but to display his physical vulnerability. In that instant, Churchill could not help but pity the man. The illusion of strength faded ever so briefly, revealing Roosevelt, in Churchill’s sentimental mind, as a ‘tragic figure’. The Soviets had covered the seat of Roosevelt’s Jeep with a Kazak carpet, which lent him the appearance of an elderly maharajah as he moved forward, with Churchill and Molotov walking alongside, to review the troops. (Churchill’s doctor, Lord Moran, described the scene less charitably, comparing the president to an elderly Queen Victoria in a phaeton, with the prime minister in the role of a lowly attendant trailing behind.)

As Roosevelt, Churchill and Molotov watched the white-gloved Soviet soldiers in knee-high boots stomping resolutely through the oily puddles, their rifles with fixed bayonets held over their shoulders in precise position, Sarah and Anna took in the scene together. The Red Army band began to play the Soviet national anthem. As she listened to the tune, Anna thought it strangely melancholy. And yet its sad air seemed appropriate in this place. As Sarah observed, they were standing in the midst of ‘a great wide open blank space of nothing covered with snow’. Any buildings that had once stood within view had been destroyed in the war.

While Sarah took in the barren horizon, Anna pulled out her camera. She had brought it to take some keepsake snapshots to share with her husband when she returned. She noticed a group of official Soviet photographers and a film crew standing nearby. Through the viewfinder of her camera, she caught a glimpse of her father, which introduced yet another worry. At home, FDR and the American press had formed a gentleman’s agreement. Newspapers refrained from printing pictures that revealed his wheelchair. Many Americans did not even realise Roosevelt did not have the use of his legs. It was unlikely that the Soviet photographers would be quite so accommodating.

It was not just Roosevelt’s disability that concerned her. Churchill seemed amused by the revlew, while Molotov looked on with a scowl, as if secretly irritated to be standing out in the foul weather for yet another parade. By contrast, Anna’s father appeared only half present, as if pasted into the tableau from a different scene altogether. Anna knew that the long day at Malta, followed by a short night of sleep on the plane, had left him more haggard than usual, but the difference between the prime minister and her father was striking. Though more than seven years younger than Churchill, FDR looked older: his cheekbones were sunken, and the lines around his mouth and jowls appeared weatherworn. He was dressed in his customary Brooks Brothers naval boatcloak, but instead of lending him the air of a dapper yachtsman, the garment seemed to swallow him, making him look more gaunt than he was. Just as Byrnes had noticed on the ship to Malta, he sat with his mouth hanging open for long stretches, sometimes staring off into the distance, his skin waxen. To a sick man, the camera lens could be incredibly unforgiving. But there was nothing Anna could do. The Soviet photographers continued to snap away.

The procession of Packards and ZiS limousines snaking across the Crimean steppe towards Yalta had only begun their journey, but Sarah could already sense they were off to a ‘sticky start’. The rough, slushy roads, pockmarked by winter and war, rattled the passengers’ bones as the convoy crawled along at a mere twenty miles per hour. At this rate, the final eighty miles to Yalta would take almost as long as the fourteen-hundred-mile flight from Malta.

The Crimea had long been a crossroads of conflict and imperialism. Since antiquity, Taurians, Greeks, Persians, Venetians, Genoese and the Tatar Khanate, a Muslim state of the Ottoman Empire, had lorded over the Crimea until, in 1783, the Russians annexed the khanate in the name of Catherine the Great. Each coloniser had left the Crimea with vestiges of its heritage; the local culture presented a mix of Mediterranean, Moorish and Russian influences. Cities such as Sevastopol derived their names from the Greek language, while the Uchan-Su waterfall, on the southern coast, took its name from the Tatar words for ‘flying water’. The natural environment was every bit as diverse. The south, known for its rich greenery, beachfront resorts and subtropical temperatures, resembled southern France, but the Crimea’s likeness to the Mediterranean quickly disappeared as one travelled inland. Behind the beaches, the Crimean mountains rose suddenly like waves thrust skywards from the depths of the Black Sea. North of the mountains, the dramatic peaks gradually gave way to the flatlands of the steppe. In summer, the steppe was like a prairie, filled with flowers and lush grasses, but in winter, a cycle of frosts and thaws left the bleak expanse shrouded in thick fog. The steppe swept less than a hundred miles north to the Kherson Oblast, where a natural border between the Crimea and the Ukrainian heartland was formed by the Sivash, a series of salt-rich lagoons nicknamed the ‘Rotten Sea’, for the putrid odour emanating from their shallow waters. Microalgae turned the Sivash a startling deep red, as if the blood spilled by thousands of soldiers over two centuries of wars fought across the peninsula had collected and pooled in the lagoons. The Crimea was one of Russia’s, and later the Soviet Union’s, most prized lands, but it always stood slightly apart from Mother Russia. The Isthmus of Perekop, a four-mile strip of land between the crimson Sivash and the Black Sea, was all that connected the Crimea to the mainland.

After what felt like ‘an eternity’, Winston grumpily turned to Sarah and asked how long she thought they had been driving.

‘About an hour,’ she replied.

‘Christ,’ he muttered sharply under his breath, ‘five more hours of this.’

Sarah knew it was hardly Averell Harriman’s fault that Yalta had been selected as the conference location, but as they drove along through the barren steppe, she could not help but join the chorus of criticism. ‘Really!’ she thought. ‘Averil [sic] must be mad’ to force Roosevelt to suffer through such a drive. As their car crawled along, Lord Moran, who was driving with Winston and Sarah, noted that the miles and miles of frozen, foggy steppe reminded him of northern England’s haunting moors covered in snow. It was an appropriate comparison. Perhaps recalling Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Sarah scribbled in a letter to her mother that the expanse of countryside looked ‘as bleak as the soul in despair!’

Once, this desolate land had been dotted with cooperative farms. Though neither Sarah nor Anna knew it as they drove south, the destruction the Nazis had wrought in the Crimea masked the brutality the Soviets had already inflicted on their own people there. The charred cooperative farms, which Stalin had organised in response to a grain shortfall in 1928, were vestiges not of agrarian prosperity destroyed by war, but of state-sponsored famine. Between 1928 and 1940, Soviet collectivisation led to the deaths of millions of peasants. Nowhere was the death toll worse than in Ukraine, where the famine disguised another objective – the Holodomor – the Soviets’ genocide of ethnic Ukrainians. And in the depopulated city of Simferopol, the Nazis had given the Soviets the conditions they needed to eliminate another ethnic minority supposedly hostile to the state. The Soviets wanted unobstructed access to the Dardanelles and Turkey, but in their way stood the Crimean Muslim Tatars, with whom the Turks shared religious and ethnic ties. Stalin tasked his ruthless NKVD chief, Lavrentiy Beria, the same man in charge of preparations at Yalta, with their removal. Beria accused the Tatars of collaborating with the Nazis, and over the course of three days in May 1944, he loaded nearly 200,000 Tatars on cattle trains and forcibly deported them to Uzbekistan, where many died in exile.

Now their farms stood abandoned. Nearly all the buildings lay in scorched ruins alongside charred remains of trains, tanks and other instruments of war, as if General Sherman had risen from the dead for an encore march to the sea halfway across the world. The only people the travellers saw as they rolled slowly southwards were Soviet soldiers, many of them women and teenage girls, who stood at attention along the road every several hundred feet. It appeared that an entire infantry division had been pulled off the line to guard the route, though the presence of these careworn soldiers could hardly have been more than ceremonial. Few carried rifles. More striking than their gender or their lack of arms were their faces. The soldiers had been drawn from the many ethnic groups that made up the Soviet Union – Russians, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Georgians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Chechens and more. Each soldier, bundled in a long, padded coat, was intended to be a nameless copy of the preceding soldier, an identical cog in the wheel of the state. But their faces betrayed individuality.

Not until the convoy reached Simferopol did any signs of daily human life appear, albeit scenes more reminiscent of black-and-white newsreels than humanity in the flesh. Simferopol was once a thriving city under Catherine the Great, but by 1945, describing it as a city was generous. The few buildings that remained standing had no heat or electricity, and the inhabitants barely seemed to belong to the modern world. Their clothes were colourless. ‘Neither gray nor brown – just plain drab,’ Anna observed from the window of the Packard she shared with her father and his Secret Service agent, Mike Reilly. The women’s skirts were voluminous, shapeless sacks, and it had clearly been years since the children had any new clothes. Over that time, they had grown. Their trousers and skirts were all too short, exposing their ankles and shins to the cold. At first, Anna thought they looked surprisingly healthy, considering the circumstances, but upon closer inspection, she saw their faces. She realised that the children, and especially the mothers, looked remarkably old. The women’s skin was deeply wrinkled, and their lower backs were permanently curved from carrying heavy burdens.

After the convoy left Simferopol and began its ascent into the mountains, the Americans briefly pulled to the side of the road to eat the sandwiches they had brought from the Quincy. But the British pressed on. Harriman had assured them that a rest house stood only forty-five minutes away, and they were eager to find it – especially Sarah, who was experiencing one of the uncomfortable realities of being one of only two women present. ‘The rest house,’ Sarah wrote with amusement to her mother, was ‘most necessary for more reasons than resting’. But the forty-five minutes passed, and it did not appear. Stale ham sandwiches and sips of brandy mollified her appetite, but they had been driving for nearly four hours, and the call of nature was growing more urgent with every passing minute. At one point, she desperately considered finding a clump of trees along the side of the road: ‘I scanned the horizon – Cars in front – press photographers behind!! Obviously no future in that!’ she told Clementine. Finally, when Sarah’s ‘hope had nearly died’, they stopped. Mercifully, they had found the house.

Sarah and Winston expected to stop only a few minutes to use the facilities, but their Soviet hosts apparently had other plans. When they finished washing, they were led into a small room. Molotov had beaten them to the rest house and now stood, grinning, beside a table ‘groaning with food and wine’. Like the overwhelmingly indulgent display of food beneath the tents at Saki, here was bounty strikingly incongruous with the dismal montages of subsistence living that the western travellers had observed over the past four hours. Ever the gracious hosts, Molotov, his deputy Andrey Vyshinsky, and the Soviet ambassador to Britain, Fedor Gusev, beckoned for them to sit. The table clearly had been laid for the three Soviet politicians, the prime minister, the president and the daughters to enjoy a sumptuous private luncheon. The Soviets had anticipated their every need. They had even constructed a ramp, covered in rugs, at the front door so Roosevelt could enter in ease and comfort.

But when he arrived a few minutes later, Roosevelt was fixated solely on the fact that several hours of driving still stretched on before them, mostly over dangerous mountain roads. As it was, they would barely reach Yalta before dark. He was exhausted and eager to press on. Observing the appalling destruction from the windows of the Packard had left him in a dark frame of mind. As they drove, he had turned to Anna and said that he wanted ‘to exact an eye for eye from the Germans, even more than ever’.

Anna, however, was desperate to get out of the car, even just for a moment. Facing the same problem as Sarah, she ‘begged’ her father ‘to be allowed to stop’ just for a moment for purposes other than dining. He could hardly deny her. But as she was the one getting out of the car, she would be the one to ‘pave the way with Mr. Molotov with a refusal’ from FDR.

When Anna entered the rest house, she discovered with ‘horror’ the spread of delicacies assembled on the table: ‘vodka, wines, caviar, fish, bread, butter – and heaven what was to follow’. FDR had never cared for lavish Russian delicacies; he had brought his own chefs to the Tehran Conference so he could eat the food he preferred. Harriman had once again arranged with Molotov for FDR to bring his own food, along with his longtime Filipino mess crew, to Yalta, but now it was not simply a matter of culinary preference. Dr Bruenn had placed FDR on a severely restricted diet to reduce his dangerously high blood pressure. Heavy, salty foods like those piled high on the table and copious amounts of alcohol were expressly prohibited. Anna knew that her father’s blood pressure had been extremely high the night before. Even small deviations from his strict diet could put him in grave danger. Even if FDR had wanted to stop for lunch to be polite, he simply could not eat the caviar, cured fish and meats that lay before her.

Anna spent the next few minutes running back and forth between her father in the car and Molotov in the house, trying to decline the invitation to lunch as graciously as possible. She had no Russian vocabulary, so she had to enlist Pavlov, the Soviet interpreter, to help her. Finally, after several awkward minutes, Anna managed to put Molotov off without sparking an international incident. She hopped back into the car, and the Americans continued on to Yalta, leaving Churchill and Sarah to feast with the Soviet foreign minister. ‘That tough old bird,’ as Anna somewhat rudely dubbed Churchill in her diary, ‘accepted with alacrety [sic] – and I left them all to go at it!’

As the Roosevelts drove away into the mountains, Anna saw neither the chagrin nor the dissatisfaction stamped across the Soviets’ faces – nor did she witness how their departure had thrust the British into an awkward position. Like FDR, Churchill had already eaten lunch in his car and wanted to travel over the mountainous roads in daylight, but for both the western leaders to depart without acknowledging the Soviets’ hospitality would have been rude, and deeply embarrassing to Molotov and his party. Trying hard to conceal their lack of appetite, Sarah and Winston dug into the feast. Only then did the look of disappointment fade from the faces of Molotov, Vyshinsky and Gusev.

The lunch was delicious, and the Churchills soon wished they had forgone their ham sandwiches. But they would not quickly forget the Americans’ hasty departure, their tail-lights growing fainter as Roosevelt drove southwest into the setting sun like the hero of an American western. Nor, for that matter, would the Soviets forget. Once, the British and the Americans had moved as a synchronised unit; each party’s words and actions perfectly complemented the other’s. But lately it seemed that a rupture had formed in this show of unity, for which the lunchtime encounter offered further evidence. The Soviets would be only too happy to exploit that rupture in the days ahead.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов