Полная версия:

The Victorian House: Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

* Sulphur was also burned to disinfect rooms after illness (see p. 317–18). It is still used today as a bactericide – in the preservation of wine and dried fruits, for example – but its effectiveness as sulphur dioxide (as it becomes on burning) may be in doubt.31

† To disperse another myth regarding middle- and upper-class women, it should be noted that a small but statistically significant percentage of births in the first year of marriage – some 12 women per 1000 – had a child within seven and a half months of marriage.35

* Note that her first-person narrative was a literary device: the personal details of her ‘I’ changed from book to book.

* As a consequence, continental Europe had professionally qualified midwives decades before Britain – which did not find the need, finally, until the beginning of the twentieth century. As things stood for most of the nineteenth century, midwives had to be licensed, but this was a Bishop’s Licence, indicating moral rather than professional qualities. To receive it the midwife had simply to be recommended by any respectable married woman, take an oath to forswear child substitution, abortion, sorcery and overcharging, and pay a fee of 18s. 4d.

* Mandell, or ‘Max’, Creighton was one of those Victorian dynamos who so astonish us today: as a young fellow at Merton he became engaged to Louise von Glehn, the daughter of a prosperous German businessman living in Sydenham. At this time fellows of Oxford colleges had to be unmarried; Creighton was so valued that the rules were changed to keep him. He soon became the incumbent of a parish in Northumberland, then in quick succession the Rural Dean of Alnwick, the Examining Chaplain to Bishop Wilberforce, Honorary Canon of Newcastle, first Dixie Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Cambridge, Canon of Worcester, Canon of Windsor, Bishop of Peterborough, representative of the English Church at the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II, Hulsean and Rede Lecturer at Cambridge. Romanes Lecturer at Oxford, and, finally, Bishop of London – all before dropping dead at the age of fifty-seven.

* It has been suggested that it was Mrs Beeton who first used the phrase ‘A place for everything, and everything in its place.’ Even if there are earlier instances, it was very much a feeling for the time: something out of place was something that was, both practically and morally, wrong.

* Dr Jaeger, a health reformer, towards the end of the century promoted his Sanitary Woollen Clothing, made of undyed knitted woollen fabric. Jaeger all-wool underwear became extremely popular. Mrs Haweis commended it as ‘the most economical, the most comfortable, and the most cleanly, seldom as the garments require washing (once a month, says the patentee), because they throw off at once the “noxious emanations” which soil the garments, and retain the benign exhalations’. Not everyone agreed. Jeannette Marshall, the daughter of a fashionable London surgeon, rejected them outright: ‘the workhouse colour is a great objection in my eyes’. Darwin’s granddaughter Gwen Raverat used ‘Jaeger’ as a synonym for dowdy (see p. 269).81

† Dr Chavasse among others thought that flannel caps prevented eye inflammations, ‘a complaint to which new-born infants are subject’.83

* By 1866 Mrs Pedley was telling new mothers about ‘clasp-pins’, which should be used for all the baby’s wants. In 1889, however, the Revd J. P. Faunthorpe still felt he needed to explain to his readers that ‘A special kind [of pin] is known as the safety pin, which has a wire loop to act as a sheath to protect the point’.84

2

THE NURSERY

IN AN IDEAL nineteenth-century world, all homes would have had a suite of rooms – a night nursery and a day nursery – ready and waiting for use after the birth of the first child, together with a full complement of servants: a monthly nurse for the first three months, then a nursemaid.

The nursery itself was a fairly new concept: J. C. Loudon, in The Suburban Garden and Villa Companion, published in 1838, had to explain to his readers that specialized rooms for children were called ‘nurseries’.1 Only twenty-five years later the idea had been so well assimilated that the architect Robert Kerr simply assumed that they were necessary when discussing the ideal house: it clearly never occurred to him that they had not always existed. Kerr’s main concern was weighing up the virtues of convenience versus segregation. Parents needed to consider that ‘As against the principle of the withdrawal of the children for domestic convenience, there is the consideration that the mother will require a certain facility of access to them.’ The size of the house and the number of servants were for him the deciding factors: ‘in houses below a certain mark this readiness of access may take precedence of the motives for withdrawal, while in houses above that mark the completeness of the withdrawal will be the chief object’.2

Outside the fantasies of upper-class living on middle-class incomes, the reality was that most houses were not big enough to make Kerr’s concern one that needed to be addressed. The bulk of the middle classes lived in houses with between two and four, or maybe five, bedrooms: hardly big enough for two separate rooms for the younger children, not counting two bedrooms for the older children of each sex, and definitely not big enough to worry about ‘facility of access’.

Within these limitations, some attempt could be made to find the children their own space. Most larger houses put the children at the top of the house, in a room or rooms near the servants’ bedroom. One of the main troubles with rooms at the top of the house was the need to carry supplies up and down. In Our Homes, and How to Make them Healthy (1883), mothers were warned that there should be no sinks on the same floor as the nursery, as ‘The manifest convenience of having a sink near to rid the nursery department of soiled water has to be weighed against the tendency of all servants to misuse such convenience, and it is best to decide against such sources of mischief’.3 That is, it was better to have servants run up and down the stairs all day with food, bedding and dirty nappies—all of which were always to be removed ‘immediately’ – rather than risk them ‘misusing’ a sink, a euphemism for throwing the contents of chamber pots into them. The transmission of disease via the all-encompassing drains was a perpetual worry (see pp. 90–91), but it is likely that most houses could afford neither running water on the top storeys nor the servants who might misuse the non-existent sinks.

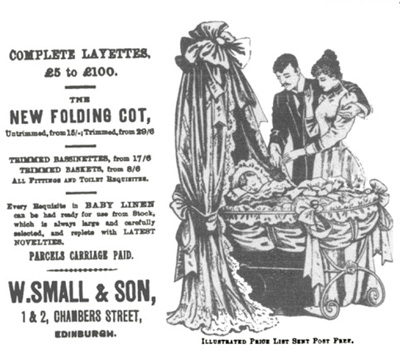

Bassinettes (also called ‘berceaunettes’ from the French for cradle) were now lavishly decorated, as in the advertisement here, and on pages 37 and 40. Perambulators were entirely new, invented only in 1850.

Health concerns were the ones given most weight – far more than convenience or affordability. One of the main reasons why it was desirable for the children to have two rooms was that they needed the ‘change of air’ that moving from one to the other would bring, because they spent

half of [their time] – at least for the very young – in the bed-room … The strong man after free respiration out of doors may pass through foul or damp air in the basement of the house with the inner breath of his capacious chest untouched; he may sit in a hot parlour without enervation, or sleep in a chilled bed-room without his vigorous circulation being seriously depressed. Not so those who stay at home; from these evils even the strong would suffer; delicate women, susceptible youth, tender children suffer most.4

Women and children needed fresh air and light more than men was the conclusion, but all the suggestions that followed concerned how they should find those things inside the house.

For houses that had the space, the standard nursery was a room or two either on the main bedroom floor or higher, which was whitewashed or distempered instead of painted or papered, so it could be redone every year. This too was for health reasons, to ensure that any infections did not linger. Kitchens were similarly repainted every year, but in that case it was to remove smells, and the accumulation of soot from around the kitchen range. The main ingredients of the nursery were all safety oriented: bars over the widows, and a high fireguard in front of the grate, securely fastened to prevent accidents. Apart from that, the requirements were few: a central table covered in wipeable oilcloth, for meals and lessons, chairs, high chairs as necessary, a toy cupboard or box, possibly a cupboard for nursery china if the children ate apart from their parents, a carpet that was small enough to lift and beat clean weekly. Mrs Panton was very firmly against gas lighting in general, and she was particularly vehement about its effects on ‘small brains and eyes [from the] glitter and harsh glare’.5 However, many balanced this against the safety of a gas bracket on the wall, out of the reach of children, and the very real danger of an oil lamp on a table that could be all too easily knocked over.

The separate nursery space, in retrospect, symbolizes the distance we perceive to have been in place between parents and their children. There is no question that, however much the Victorians loved their children, they spoke of them, and thought of them, in a very different way than we have come to expect today. How much was manner, how much representative of actual distance, needs to be considered. For it appears that some parents might have been not merely ignorant of their children’s daily routines and needs, but proud of such ignorance. Initially this might be thought of as a purely upper-class trait, fostered by large numbers of servants, yet it occurred across the social spectrum. Molly Hughes was the child of a London stockbroker who died in a road accident in 1879, at the age of forty, leaving his family perilously near to tipping down into the lower middle class. As a young woman, Molly had to go out to work as a schoolteacher. However, when she was married and able to leave paid employment, she was careful to note in her autobiography that she knew little about children, and relied for information on her servant: ‘“How often should we change her nightdress, Emma?” I asked. The reply was immediate and unequivocal – “Oh, a baby always looks to have a clean one twice a week.” [Emma] knew also the odd names for the odd garments that babies wore in that era – such as “bellyband” (about a yard of flannel that was swathed round and round and safety-pinned on) and “barracoat” …’ Molly’s sister-in-law affected the same blankness when Molly was first pregnant: ‘She took the greatest interest, and loaded me with kindness, but in the matter of what to do about a baby she was, or pretended to be, a blank. “When I was married,” she said, “all I knew about a baby was that it had something out of a bottle, and I know little more now.”’6

Molly recognized pretend-ignorance in her sister-in-law, even if she did not see the same in herself. Caroline Taylor had a similar sort of background: she was the granddaughter of a shopkeeper in Birmingham; her father was a permanently out-of-work engineer. She described relations between her parents and their children tersely: it was one of ‘stiff formality’.7

Mrs Panton, the daughter of a successful artist, supported herself, and probably placed herself in the upper reaches of the middle classes – though it is to be questioned whether professional families would have concurred. She strove to catch the right tone. In her work on domestic life, she said that a good nurse would never allow ‘her baby to be a torment … She turns them out always as if they had just come out of a band-box, and one never realises a baby can be so unpleasant so long as she has the undressing of them.’ Later she added, ‘I do not believe a new baby is anything but a profound nuisance to its relations at the very first’, and a new mother would require ‘at least a week to reconcile herself to her new fate’. Children could be ‘distracting and untidy’.8

Mrs Beeton, as we saw, thought a feeding child was a ‘vampire’. Caroline Clive, an upper-middle-class woman, thought more or less the same: she referred to her child coming to ‘feed upon me’, and she confessed that, although she loved him now, a couple of months after his birth, ‘I did not care very much about him the two first days.’9 Louise Creighton said of her husband on the birth of their first child, ‘Max, who later was so devoted to children, had not really yet discovered that he cared about them. I am doubtful of the value of what is called the maternal instinct in rational human beings.’10

The higher up the social scale, the more open about this distance from their children the parents were. Ursula Bloom’s grandmother, at least in family legend, forgot to take her baby when leaving its grandparents’ in the country: ‘She had never cared too much for children,’ said her granddaughter, perhaps unnecessarily.*12 Those lower down the ladder reflected the same views in smaller ways. Georgiana Burne-Jones, the wife of the then-struggling Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, referred to their first child as ‘the small stranger within our gates’.13 As the daughter of a Methodist minister, she knew the original Bible verse, and was not just thoughtlessly parroting the standard usage whereby a baby was ‘a little stranger’. Deuteronomy 14:21, detailing the laws concerning food, says, ‘Ye shall not eat of anything that dieth of itself: thou shalt give it to the stranger that is in thy gates, that he may eat it.’ Was the stranger within the gates a second-class citizen?

Possibly not: but the expression does reinforce the shift that has occurred over the past 150 years, from a parent-centred universe to our own child-centred one. In earlier centuries households were run by adults for adults. Children were an integral part of a functioning economic unit – whether as providers of labour in less prosperous families or as potential items of value in the business and marriage markets for the wealthier. Children were to be trained and disciplined, both to promote their own well-being and to promote the well-being of the family unit. In addition, various of the more fundamentalist versions of Christianity had said that to spare the rod was not simply to spoil the child in practical matters, but to spoil his soul. Original sin, thought the Evangelicals, meant that all children were born needing to find salvation.

In less religious houses this developed into a sense of authority for authority’s sake. Samuel Butler wrote of his father’s childhood early in the century, as well as his own, in his semi-autobiographical novel The Way of All Flesh (1873–80):

If his children did anything which Mr. Pontifex disliked they were clearly disobedient to their father. In this case there was obviously only one course for a sensible man to take. It consisted in checking the first signs of self-will while his children were too young to offer serious resistance. If their wills were ‘well broken’ in childhood, to use an expression then much in vogue, they would acquire habits of obedience which they would not venture to break through … 14

As the century progressed, improved standards of living meant that many children who would earlier have gone out to work now had a childhood. Further, Rousseau’s theories of child education, promoting the ideal of individual development in natural surroundings, struck a chord, and converged with the Romantic movement’s eloquence on the innocence and purity of childhood. Many books agreed with the Revd T. V. Moore in his ‘The Family as Government’ in The British Mothers’ Journal, when he advised parents that ‘The great agent in executing family law is love.’15

Yet while physical coercion was used less as the century progressed, and persuasion more, there was little doubt about the virtues of authority and obedience. Frances Power Cobbe, a philanthropist and worker for women’s rights, outlined in her Duties of Women what was to be expected from a child by way of obedience:

1st. The obedience which must be exacted from a child for its own physical, intellectual, and moral welfare.

2nd. The obedience which the parent may exact for his (the parent’s) welfare or convenience.

3rd. The obedience which parent and child alike owe to the moral law, and which it is the parent’s duty to teach the child to pay.16

Moral law was to many synonymous with religious law. It enshrined the duty of obedience owed to God. The head of the family derived his authority from God; the wife of the head derived hers from the head; and so on. Any disobedience subverted this notion of order. Therefore disobedience was, of itself, subversive, and it was the idea of rebellion that needed to be punished, not whatever the act of disobedience itself was. Laura Forster, a clergyman’s daughter (and later the aunt of E. M. Forster), noted that ‘We were expected to be obedient without any reason being given’, but she tried to give extenuating circumstances: ‘we shared our mother’s confidence as soon as we were of a suitable age, and I think this helped to give us the conviction that we all had that nothing was forbidden us capriciously, and that some day we should know, if we did not understand at the time, why this or that was forbidden’.17

Most parents felt that discipline could not begin too early. A mother or nurse’s refusal to feed her infants except at stated hours taught the infants the benefits of ‘order and punctuality’.18 Having their crying ignored taught babies self-restraint: Mrs Warren said that, if a child cried for something, on principle it should never be given – ‘even a babe of three months, when I held up my finger and put on a grave look, knew that such was the language of reproof.’ Instead of beatings, which children earlier in the century might have routinely expected, children were told of the disappointment they caused, to their parents and to God. Mrs Warren suggested that children who were disobedient should be told they were breaking the Fifth Commandment, by not honouring their fathers and mothers;19 Mary Jane Bradley, wife of a master at Rugby School, told her son that ‘God was looking at him with great sorrow and saying “that little boy has been in a wicked passion, he cannot come up and live with me unless he is good”.’20

Corporal punishment, although lessened in force and frequency, vanished only slowly over the next hundred years. When Mary Jane Bradley’s son Arthur (nicknamed ‘Wa’) was three, ‘He was not good yesterday and surprised me by saying, “Wa was naughty in London Town and Papa and Mama did whip Wa very hard” – I did not believe he could have remembered anything so long ago [three months before]. This whipping certainly had its effect. It was the first and last.’21 Louise Creighton, who said that in her own childhood she was never beaten, but put in a dark cupboard that induced only boredom, punished her own children in a way she acknowledged ‘may be considered brutal by some people. Cuthbert was a very mischievous boy, & used to play with fire & cut things with knives, so when he played with fire I held his finger on the bar of the grate for a minute that he might feel how fire burnt, & when he cut woodwork with his knife I gave his fingers a little cut.’ Despite what might today be described as savagery, she thought it important to end, ‘I never whipt any child.’22 What seemed harsh changed over time. A guide to the sickroom advised, almost in passing, that if a child refused medicine, ‘at once fasten the child’s hand behind him, throw him on his back, pinch his nose to force his mouth apart, and … pour [the liquid] down his throat with a medicine spoon’. This is called acting with ‘firmness’.23

It was still, however, a different world to the one in which Mr Pontifex had ruled. Children were moving to the centre of their parents’ lives. This was displayed in graphic form over the century by the pattern books that furniture-makers and shops produced to advertise their wares. In the early part of the nineteenth century there was no furniture made specifically for children; then in 1833 Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture (which, despite its name, was a very metropolitan, bourgeois publication) had a short section for children’s furniture, most of it miniaturized versions of adult objects. By the end of the century every shop and every catalogue had a full range of furniture designed specially for children’s needs.24

Different families adapted to this new ethos more or less quickly and comfortably: how quickly and comfortably was based on character and on personal and social background. Many remained convinced that the marital relationship was the primary one: Louise Creighton reported that Walter Pater’s sister had once said to her about the novelist Mrs Humphry Ward and her husband that ‘she always preferred Mary [Ward]’s company when Humphry was present, because if he was absent Mary was always wondering where he could be; but she preferred me without Max, for when he was there I was so occupied with him & with what he was saying that I was no use to anyone else … I think this was true all my life.’ She did not make the connection with her own mother’s behaviour in her childhood: when Mr von Glehn was due back from London in the evenings ‘My mother always grew expectant some time before his train arrived & was very fidgety & anxious.’ Her husband was her focus, as had been her mother’s, and ‘only the fact that I nursed [my children] kept me from going about much, and this … did prevent me sharing many of Max’s expeditions & walks which was a very real deprivation’.25

Advice books, fiction and reality converge here: Mrs Warren’s model housewife always made her children understand that when their father came home from work he was to be considered first in all things, otherwise she felt it was entirely to be expected if he became ‘cold and indifferent’.26 Mrs Panton believed children should have rooms where they do not ‘interfer[e] unduly with the comfort of the heads of the establishment’.27 Many novels touched on the same theme: in George Gissing’s New Grub Street the failed novelist Edwin Reardon looks back on his collapsing marriage: ‘Their evenings together had never been the same since the birth of the child … The little boy had come between him and his mother, as must always be the case in poor homes.’28 His view is that marriages prosper not because they become child-centred, but because the family can afford servants to remove the children from the adult sphere.

Mrs Henry Wood, in East Lynne, provided the clearest apologia for this adult-centred view. Mr Carlyle’s second wife expounds her views to her predecessor, Lady Isabel (for complex plot reasons currently disguised as a French governess, Mme Vine). The two women agree on this point, and as the reader has spent hundreds of pages learning to sympathize with Lady Isabel it is hard to imagine that theirs was not Mrs Henry Wood’s view too. It is worth quoting at length, for the insight it gives into the adult-centred world-view. Mrs Carlyle says:

I never was fond of being troubled with children … I hold an opinion, Madame Vine, that too many mothers pursue a mistaken system in the management of their family. There are some, we know, who, lost in the pleasures of the world, in frivolity, wholly neglect them: of those I do not speak; nothing can be more thoughtless, more reprehensible, but there are others who err on the opposite side. They are never happy but when with their children; they must be in the nursery; or, the children in the drawing-room. They wash them, dress them, feed them; rendering themselves slaves … [Such a mother] has no leisure, no spirits for any higher training: and as they grow old she loses her authority … The discipline of that house soon becomes broken. The children run wild; the husband is sick of it, and seeks peace and solace elsewhere … I consider it a most mistaken and pernicious system …