Полная версия:

The Victorian House: Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

Yet even when the occupancy was dense, Mrs Haweis, an arbiter of fashionable interior decoration in several books, was firm about segregation of function: ‘Gentlemen should be discouraged from using toilet towels to sop up ink and spilt water; for such accidents, a duster or two may hang on the towel-horse.’4 That this warning was necessary implies that ink was regularly used in a room where there was a towel rail, and from Mrs Haweis’s detailed description that could only be the bedroom. This was clearly an on-going situation. Aunt Stanbury, Trollope’s resolutely old-fashioned spinster in He Knew He Was Right twenty years later, loathed this promiscuous mixing: ‘It was one of the theories of her life that different rooms should be used only for the purposes for which they were intended. She never allowed pens and ink up into the bed-rooms, and had she ever heard that any guest in her house was reading in bed, she would have made an instant personal attack upon that guest.’5

Bedroom furniture varied widely, from elaborate bedroom and toilet suites, to cheap beds, furniture that was no longer sufficiently good to be downstairs in the formal reception rooms, and old, recut carpeting. Mrs Panton describes the bedrooms of her youth in the 1850s and 1860s with some feeling – particularly

the carpet, a threadbare monstrosity, with great sprawling green leaves and red blotches, ‘made over’ … from a first appearance in a drawing-room, where it had spent a long and honoured existence, and where its enormous design was not quite as much out of place as it was in the upper chambers. Indeed, the bedrooms, as a whole, seemed to be furnished as regards a good many items out of the cast-off raiment of the downstairs rooms.6

As the daughter of W. P. Frith, an enormously popular painter, Mrs Panton had hardly grown up in a house where the taste was either lacking or unable to be achieved through scarcity of money. Nor was her childhood home, to use one of her favourite words, ‘inartistic’: this make-do-and-mend system was the norm.

By mid-century, bedrooms were beginning to be furnished to the standards of the reception rooms, where possible. This meant a good carpet, furniture (mahogany for preference) that included a central table, a wardrobe, a toilet table, chairs, a small bookcase and a ‘cheffonier’, a small, low cupboard with a sideboard top. The bed, if possible, was still four-postered, with curtains. There was also a washstand, in birchwood (which, unlike darker woods, did not show water stains), with accoutrements, a pier glass, and perhaps a couch or chaise longue. In Arnold Bennett’s The Old Wives’ Tale, in which he reworked some of his childhood memories from the Potteries of the 1870s, the master bedroom of the town’s chief linen-draper was splendid with ‘majestic mahogany … crimson rep curtains edged with gold … [and a] white, heavily tasselled counterpane’.7

Multi-functionality: a suggestion for a bedroom writing table with, over it, a combination bookshelf and medicine case for when the bedroom was required to double as a sickroom.

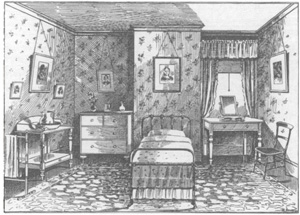

Heal’s and Son, the great furniture shop on Tottenham Court Road, suggested a bedroom furnished in Aesthetic style for the prosperous. Note that by 1896 the bed has no hangings, and gas jets illuminate the dressing mirror, although not the bed, which still has no bedside table.

The range of furniture varied with income and taste. A mahogany wardrobe cost anything from 8 to 80 guineas, while an inexpensive cupboard could be made in the recess of the chimney breast, simply using a deal board, pegs and a curtain in front. Trays and boxes for storing clothes were common – hangers were not in general use until the 1900s (when they were referred to as ‘shoulders’), so clothes either hung from pegs or were folded. Small houses and yards of fabric in every dress meant that advice books were constantly contriving additional storage: in hollow stools, benches, ottomans. Even bulkier items were folded: Robert Edis, another interiors expert, recommended that halls should have cupboards ‘with shelves arranged for coats’.8 ‘Ware’ – shorthand for toilet-ware – also came in a range of qualities. The typical washstand had towel rails on each side, and often tiles at the back to protect against splashing water. It was expected there would be a basin, a ewer or jug, a soapdish, a dish to hold a sponge, a dish to hold a toothbrush, a dish to hold a nailbrush, a water bottle and a glass. A chamber pot might be of the same pattern as the ware. Mrs Panton recommended that identical ware should be bought for most of the bedrooms, as breakages could then be replaced from stock – breakages of bedroom items, she implied, were frequent. A hip bath might also live in the bedroom, to be filled by toilet cans: large metal cans of brass or copper, which were used to carry hot water up from the kitchen.

No room was finished without its ration of ornaments: Mrs Haweis said that even without much money one could have a pretty room: ‘A little distemper in good colours, one or two really graceful chairs … a few thoroughly good ornaments, make a mere cell habitable.’9 Mrs Caddy, in her book on Household Organization, suggested that, as with the furniture and carpets, second best would do for the bedroom – ‘light ornaments … which may be too small, or too trifling, to be placed with advantage in the drawing room’.10 Certainly the desire for small decorative objects was no less upstairs than down. Marion Sambourne’s dressing table in the 1880s had on it five jewel boxes, a brush-and-comb set, a card case, two sachets, six needlework doilies, three ring trays, a pin cushion and a velvet ‘mouchoir case’.11

Bedside tables as we know them were not current. In sickroom literature, nurses were always being advised to bring a table to the bedside to hold the medicines. Mrs Panton, with her love of soft furnishings, suggested for the healthy ‘a bed pocket made out of a Japanese fan, covered with soft silk, and the pocket itself made out of plush, and nailed within easy reach’, to hold a watch, a handkerchief etc., and then, as an innovation which required explanation, ‘furthermore … great comfort is to be had from a table at one’s bedside, on which one can stand one’s book or anything one may be likely to want in the night’.12

Mrs Panton’s bed was a brass half-tester, which had fabric curtains only at the head, lined to match the furniture. This was in keeping with the style of the later part of the century. As more became known about disease transmission, home decorators were urged to keep bedroom furnishings to a minimum, although this frequently given advice must be compared to actuality. A list of objects in Marion Sambourne’s room included a wardrobe, a cupboard to hold a chamber pot, a towel rail, a sofa, a box covered in fabric, two tables, a bookcase, a linen basket, a portmanteau, a vase, two jardinières, plus ten chairs and the dressing table with its display.13 For not all agreed that bed-hangings were unhealthy: Cassell’s Household Guide as late as 1869 thought that draughts were more of a worry than the hangings that kept them away from the sleeper.14 In general, however, four-posters were vanishing. Even if people were not switching to simple iron or brass beds, as advised, they were at least replacing the traditional heavy drapery with beds with only vestigial curtains. The simplified lines of such beds were disturbing to some: Mrs Panton advised that ‘If the bare appearance of an uncurtained bed is objected to’, one could mimic the more familiar style by putting the startlingly naked bed in a curtained alcove.15 Likewise, while carpets did not disappear entirely, they were modified so that they could be taken up and beaten regularly, or rugs were substituted, so that the floor could be scrubbed every week.

As the second half of the century progressed, hygiene became the overriding concern. Mrs Panton, still distressed about bedroom carpets, remembered a carpet that had spent twenty years on the dining-room floor, ‘covered in holland in the summer,* and preserved from winter wear by the most appallingly frightful printed red and green “felt square” I ever saw’. When it was no longer considered to be in good condition, it was moved to the schoolroom, then demoted once more, to the girls’ bedroom. (Note that the schoolroom, a ‘public’ room for children, got the carpet before the children’s bedroom did.) After that, it was cut into strips and put by the servants’ beds, ‘and when I consider the dirt and dust that has become part and parcel of it, I am only thankful that our pretty cheap carpets do not last as carpets used to do, for I am sure such a possession cannot be healthy’.16

As suggested by Heal’s for a servant’s bedroom. Instead of modern peacock-feather wallpaper (p. 5), the servants make do with old-fashioned flowers, and plain deal furniture replaces the more elaborate versions given to their employers. Many of the middle classes slept in rooms much like these.

Hygiene was not just a matter of dust. Three things were paramount: the extermination of vermin (which encompassed insects as well as rodents), the protection from dirt of various kinds, and the proper regulation of light. Gas lighting was not recommended for bedrooms. If gas was used, the servants lit the bedroom lights in the evenings while the family was still downstairs; by bedtime much of the oxygen in the room would have been depleted by it; the fireplace, being seldom if ever lit, added no ventilation, and in cold weather, with closed windows, a headache was the least the sleeper could expect to awake to. A single candle, brought upstairs on retiring, was the approved bedroom lighting, but for the more prosperous a pair of candlesticks on the mantel, and another on the dressing table, ‘with the box of safety matches in a known position, where they can be found in a moment’, was more comfortable.*18

The lack of lighting was complicated by the fact that the bed needed to be positioned carefully to meet the conflicting demands of health and privacy. The bed should be ‘screen [ed], and not expose [d]’ by the opening of the bedroom door, and yet at the same time, it could not be placed in a draught from the window, door or fireplace, nor should there be overmuch light (which could be ‘trying’ when the occupant was ill).19 Given these many requirements, and the limited floor plans of most terraced houses, these niceties were probably acknowledged more in the abstract than they were practised.

Protection from dirt was still more difficult. Dust was not just the airborne particles, causing no particular damage, that we know. Our Homes warned that

Household dust is, in fact, the powder of dried London mud, largely made up, of course, of finely-divided granite or wood from the pavements, but containing, in addition to these, particles of every description of decaying animal and vegetable matter. The droppings of horses and other animals, the entrails of fish, the outer leaves of cabbages, the bodies of dead cats, and the miscellaneous contents of dust-bins generally, all contribute … and it is to preserve a harbour for this compound that well-meaning people exclude the sun [by excessive drapery], so that they may not be guilty of spoiling their carpets.20

Compounded with this, coal residue was omnipresent, both as dust when coals were carried to each fireplace and then, after the fires were lit, as soot thrown out by the fire, blackening whatever it touched. The most common system of protection was to cover whatever could be covered, and wash the covers regularly. However, as the covers became decorative objects in themselves, they became less and less washable. Dressing tables, for example, were usually covered with a white ‘toilet cover’. Mrs Panton recommended, as more attractive, her own version, which was a tapestry cover, ‘edged with a ball fringe to match’. She also had ‘box pincushions’ made out of old cigar boxes to hold gloves and other small objects: the boxes were given padded tops, and were then covered in plush, velveteen or tapestry, and fringed ‘so that the opening is hidden’. These covers were now themselves in need of covers: tapestry could be brushed and dabbed with benzene or other dry-cleaning fluids, but it could not be easily washed; nor could velvet or plush, and especially not fringes. Yet Mrs Panton was deeply concerned with airborne dirt: she noted that ‘in dusty weather particularly, and especially if we drive much’, it was impossible to keep a hairbrush clean – ‘our brushes look black after once [sic] using’. She suggested that three hairbrushes be kept in rotation: one to start the day clean; the second to be washed and set out to dry for the following day; and one spare to lend a friend should she need it.21 If hair, covered by a hat, got so dirty on a single outing, the amount of dust and dirt that landed on clothes and furniture is almost inconceivable.

The extermination of vermin was an even more pressing problem, and, apart from the kitchen, beds were the most vulnerable places in the house. Bedding was rather more complicated than we have learned to expect. Mattresses were of organic fibre: horsehair mattresses were the best; cow’s-hair ones were cheaper, although they did not wear as well; even less expensive were wool mattresses. A straw mattress, or palliase, could be put under a hair mattress to protect it from the iron bedstead.22 Chain-spring mattresses were available in the second half of the century, but they were expensive, and they still needed a hair mattress over them. It was recommended that a brown holland square should be tied over the chains, to stop the hair mattress from being chewed by the springs. The hair mattress itself then needed to be covered with another holland case, to protect it from soot and dirt. If the bed had no springs, a feather bed – which was also expensive, hard to maintain, and a great luxury – could be added on top of the mattress. An underblanket, called a binding blanket, was recommended over the hair mattress.

After the basics (all of which needed turning and shaking every day, as otherwise the natural fibre had a tendency to mat and clump), the bedding for cold, usually fireless rooms consisted of an under sheet (tucked into the lower mattress, not the upper, again to protect from soot), a bottom sheet, a top sheet, blankets (three to four per bed in the winter), a bolster, pillows, bolster-and pillow-covers in holland, and bolster- and pillow-cases.

With all of this bedding made of organic matter, it is hardly surprising that bedbugs were a menace. Oddly, the usually fastidious Mrs Haweis thought that blankets needed washing only every other summer, although sheets needed washing every month –‘the old-fashioned allowance’ – if on a single bed; if two people were sharing a bed it was every fortnight. Not all the sheets were changed at once: bottom sheets were taken off, as were the pillow-and bolster-cases, and the top sheet was moved down and became the bottom sheet for the next fortnight.* It was recognized that it was impossible to go to bed clean: Mrs Haweis noted that pillowcases needed to be changed ‘rather oftener [than the sheets], chiefly because people (especially servants) allow their hair to become so dusty, that it soils the cases very soon’.†23

The main cleaning of bedding came twice a year, in the spring and autumn cleanings, when it was recommended that the mattresses and pillows were taken out and aired (and, every few years, taken apart, the lumps in the ticking broken up and washed, and the feathers sifted, to get rid of the dust).*24 Clearly, this kind of work could take place only with substantially more space and labour than many, if not most, middle-class households could afford. As was often the case, the advice books were describing the daily routines of upper-middle-class houses, or an ideal world that did not exist at all.†

It was not, however, enough simply to clean the bedding as well as possible. Although vermin had always been present, for some reason in the eighteenth century their numbers increased,25 possibly because of rapid urbanization. After a vigorous war against them, by the 1880s Mrs Haweis could say that fleas were not expected in ‘decent bedrooms’, although ‘at any minute one may bring a stray parent in from cab, omnibus, or train’;26 consequently vigilance had to be maintained, and the bed itself had to be examined regularly. And examine the Victorians did. Beatrix Potter wrote with an air of doom fulfilled about a Torquay hotel, where she was holidaying:

I sniffed my bedroom on arrival, and for a few hours felt a certain grim satisfaction when my forebodings were maintained, but it is possible to have too much Natural History in a bed.

I did not undress after the first night, but I was obliged to lie on [the bed] because there were only two chairs and one of them was broken. It is very uncomfortable to sleep with Keating’s [bug] powder in the hair.27

At home, the good housewife was supposed to check the bed and bedding every week. When Thomas and Jane Carlyle moved into their Cheyne Row house in 1834, Jane claimed that hers was the only house ‘among all my acquaintances’ that could boast of having no bugs. For a decade all was well. Then in 1843 bugs were found in the servant’s bed in the kitchen:

I flung some twenty pailfuls of water on the kitchen floor, in the first place to drown any that might attempt to save themselves; when we killed all that were discoverable, and flung the pieces of the bed, one after another, into a tub full of water, carried them up into the garden, and let them steep there for two days; – and then I painted all the joints [with disinfectant], had the curtains washed and laid by for the present, and hope and trust that there is not one escaped alive to tell. Ach Gott, what a disgusting work to have to do! – but the destroying of bugs is a thing that cannot be neglected.28

Ten years later she gave up that particular war: when the servant’s bed was again found to be swarming, she sold the old wooden bed and bought an iron one: ‘The horror of these bugs quite maddened me for many days.’29 That, she thought, was that – until a few years later Carlyle complained about his own bed. Jane was initially confident:

Living in a universe of bugs outside, I had entirely ceased to fear them in my own house, having kept it for so many years perfectly clean from all such abominations. But clearly the practical thing to be done was to go and examine his bed … So instead of getting into a controversy that had no basis, I proceeded to toss over his blankets and pillows, with a certain sense of injury! But on a sudden, I paused in my operations; I stopped to look at something the size of a pin-point; a cold shudder ran over me; as sure as I lived it was an infant bug! And, O, heaven, that bug, little as it was, must have parents – grandfathers and grandmothers, perhaps!30

The carpenter was called to dismantle the bed. The usual system at this stage was to take the pieces of the bed, and all the bedding, into an empty room, or outside, wash the bed frame with chloride of lime and water, and sprinkle Keating’s powder everywhere; then wait and repeat daily for as long as necessary. If the infestation was out of control, the bed and mattress were left in an empty room which was sealed to make it airtight, and then sulphur was burned to disinfect the bed and the surrounding area, to prevent the spread of the problem to the walls and floors.*32

Another anxiety was that laundry sent out to washerwomen would come back infested,33 and, for the same reason, secondhand furniture was distrusted – ‘How can we know we are not buying infection?’34

Even if the major infections – cholera, typhoid, diphtheria – were set to one side, the women who used these bedrooms spent, by the 1870s, approximately twelve years of married life either pregnant or breastfeeding: they were often, in terms of health, at a disadvantage in the bedroom. Women had an average of 5.5 births (although somewhat fewer children were born alive), with 80 per cent of women having their first child within a year of marriage.†36 Marriage and motherhood were virtually synonymous to many.

Advice literature, which proliferated in all walks of life, really came into its own regarding childbirth. Motherhood, the books implied, was a skill to be acquired, not innate behaviour. Nor was it to be acquired simply by watching one’s own mother. Books on this subject in the early part of the century were written by clergymen, and were most concerned with the spiritual aspects of child-rearing. In the second half of the century motherhood was ‘professionalized’, and doctors, teachers and other experts took over. A Few Suggestions to Mothers on the Management of their Children, by ‘A Mother’ (1884), was confident that mothers could not act ‘without knowledge or instruction of any kind … [the belief that they could] is one of the popular delusions which each year claims a large sacrifice of young lives.’37 It was not just ignorance these books wanted to combat. For their authors, what women knew was even more suspect than what they did not know: mothers ‘are cautioned to distrust their own impulses and to defer to the superior wisdom of the medical experts’.38

The first signs of pregnancy were not easy to detect. Mid-century, Dr Pye Chavasse, author of Advice to a Mother on the Management of her Offspring (a book so popular it was still in use at the turn of the century) and other similar works, gave the signs of pregnancy, in order of appearance, as ‘ceasing to be unwell’ (i.e. menstruate); morning sickness; painful and enlarged breasts; ‘quickening’ (which would not have been felt until the nineteenth week); increased size. That meant that no woman could be absolutely certain she was pregnant until the fifth month. As early as the 1830s it had been known to doctors that the mucosa around the vaginal opening changed colour after conception, yet this useful piece of information did not appear in a lay publication until the 1880s, and the doctor who wrote it was struck off the medical register – it was too indelicate, in its assumption that a doctor would perform a physical examination. Neither doctors nor their patients felt comfortable with this.39 Discussion itself was allusive. Mrs Panton, at the end of the 1880s, felt she could ‘only touch lightly on these matters [of pregnancy]’ because she didn’t know who might read her book. Kipling, from the male point of view, was very much of his time when he wrote, ‘We asked no social questions – we pumped no hidden shame – / We never talked obstetrics when the Little Stranger came –’.40

It would be pleasant to be able to refute the idea that middle-class Victorians found in pregnancy something that needed to be hidden, but that really was the case. Pregnancy for them was a condition to be concealed as far as possible. Mrs Panton called her chapter on pregnancy ‘In Retirement’, and never used any word that could imply pregnancy. Instead, it was ‘a time … when the mistress has perforce to contemplate an enforced retirement from public life’.41 Ursula Bloom, who told her upper-middle-class mother’s story, noted that ‘it would have been unpropitious if a gentleman had caught sight of her … Even Papa was supposed to be ignorant of what was going on in the house … He did not enquire after Mama’s nausea … and her occasional bursts of tears.’42 The class aspect was important. Cassell’s Household Guide warned expectant mothers:

When a woman is about to become a mother, she ought to remember that another life of health or delicacy is dependent upon the care she takes of herself … We know that it is utterly impossible for the wife of a labouring man to give up work, and, what is called ‘take care of herself,’ as others can. Nor is it necessary. ‘The back is made for its burthen.’ It would be just as injurious for the labourer’s wife to give up her daily work, as for the lady to take to sweeping her own carpets or cooking the dinner … He who placed one woman in a position where labour and exertion are parts of her existence, gives her a stronger stage of body than her more luxurious sisters. To one inured to toil from childhood, ordinary work is merely exercise, and, as such, necessary to keep up her physical powers.43