Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

Of one or two legal curiosities now extinct, I may mention “Benefit of Clergy,” an institution established in our early history, in order to screen a clerk, or learned man, from the consequences of his crime. In case of felony, one had but to plead ability to read, and prove it, and the sentence was commuted to branding the hand with a hot iron. It was a privilege much abused, but it lingered on until 1827, when it was abolished by the Act, 7 and 8 Geo. IV. cap. 28.

Another curious custom, now also done away with, we meet with, in an advertisement in the Morning Herald, March 17, 1802: “Wanted, one or two Tyburn Tickets, for the Parish of St. George’s, Hanover Square. Any person or persons having the same to dispose of, may hear of a purchaser,” &c. These tickets were granted to a prosecutor who succeeded in getting a felon convicted, and they carried with them the privilege of immunity from serving all parochial offices. They were transferable by sale (but only once), and the purchaser enjoyed its privileges. They were abolished in 1818. They had a considerable pecuniary value, and in the year of their abolition, one was sold for £280!

“Tyburn” reminds us of the fearful numbers sentenced to death at that time. The law sadly wanted reformation in this respect; besides murder, coining, forgery, &c., many minor offences were punishable with death, although all convicted and sentenced were not executed; some being reprieved, and punished with transportation. George III. had a great dislike to capital punishment, and remitted the sentence to as many as he could. Take as an example of the awful severity of the law, only one sessions at the Old Bailey, ending September 24, 1801: “Sentence of death was then passed upon Thomas Fitzroy, alias Peter Fitzwater, for breaking and entering the dwelling-house of James Harris, in the daytime, and stealing a cotton counterpane. Wm. Cooper for stealing a linen cloth, the property of George Singleton, in his dwelling-house. J. Davies for a burglary. Richard Emms for breaking into the dwelling-house of Mary Humphreys, in the daytime, and stealing a pair of stockings. Richard Forster for a burglary. Magnus Kerner for a burglary, and stealing six silver spoons. Robert Pearce for returning from transportation. Richard Alcorn for stealing a horse. John Nowland and Rd. Freke for burglary and stealing four tea spoons, a gold snuff-box, &c. John Goldfried for stealing a blue coat. Joseph Huff, for stealing a lamb, and John Pass for stealing two lambs.”

In fact, the “Tyburn tree” was kept well employed, and yet, apparently, the punishment of death hardly acted as a deterrent. A sad, very sad street cry, yet one I have often heard, was of these poor wretches; true, it had been made specially to order, in Catnach’s factory for these articles, in Monmouth Court, Seven Dials; but still it was the announcement of another fellow-creature having been done to death.

The executions which would arise from the batch of sentences I have just recorded, would take place at Newgate. The last person hanged at Tyburn, having suffered, November 7, 1783, and the above illustration shows in a peculiarly graphic manner, the condemned sermon, which was preached to those about to die on the morrow. To make the service thoroughly intelligible to them, and to impress them with the reality of their impending fate, a coffin was set in the midst of the “condemned pew.”

Crowds witnessed the executions, which took place in the front of Newgate, and on one occasion, on the 23rd of February, 1807, an accident occurred, by the breaking of the axle of a cart, whereon many people were standing; they were not only hurt, but the crowd surged over them, and it ended in the death of twenty-eight people, besides injuries to many more.

We have seen, in February, 1885, a murderer reprieved, because the drop would not act; but in the following instance, the criminal did suffer, at all events, actual pain. It happened at Jersey, on the 11th of May, 1807, and is thus chronicled in the Annual Register for that year: “After hanging for about a minute and a half, the executioner suspended himself to his body; by whose additional weight the rope extended in such a manner that the feet of the criminal touched the ground. The executioner then pulled him sideways, in order to strangle him; and being unable to effect this, got upon his shoulders; when, to the no small surprise of the spectators, the criminal rose straight upon his feet, with the hangman upon his shoulders, and loosened the rope from his throat with his fingers. The Sheriff ordered another rope to be prepared; but the spectators interfered, and, at length, it was agreed to defer the execution till the will of the magistrates should be known. It was subsequently determined that the whole case should be transmitted to His Majesty, and the execution of the sentence was deferred till His Majesty’s pleasure should be known.”

A platform which suddenly disappeared from under the criminal seems to have been invented in 1807, for we read under 27th of July of that year, that John Robinson was executed at York “on the new drop,” but something of the same kind had certainly been used in 1805.

As a rule, the poor creatures died creditably; but there is one case to the contrary, which is mentioned in the European Magazine, vol. xlvii. pp. 232-40. A man named Hayward was to be hanged for cutting and maiming another. The scene at the execution is thus described: “When the time for quitting the courtyard arrived, Hayward was called to a friend to deliver him a bundle, out of which he took an old jacket, and a pair of old shoes, and put them on. ‘Thus,’ said he, ‘will I defeat the prophecies of my enemies; they have often said I should die in my coat and shoes, and I am determined to die in neither.’ Being told it was time to be conducted to the scaffold, he cheerfully attended the summons, having first ate some bread and cheese, and drank a quantity of coffee. Before he departed, however, he called out, in a loud voice, to the prisoners who were looking through the upper windows at him, ‘Farewell, my lads, I am just a going off; God bless you!’ ‘We are sorry for you,’ replied the prisoners. ‘I want no more of your pity,’ rejoined Hayward; ‘keep your snivelling till it be your own turn.’ Immediately on his arrival upon the scaffold, he gave the mob three cheers, introducing each with a ‘Hip, ho!’ While the cord was preparing he continued hallooing to the mob.

“It was found necessary, before the usual time, to put the cap over his eyes, besides a silk handkerchief, by way of bandage, that his attention might be entirely abstracted from the spectators… He then gave another halloa, and kicked off his shoes among the spectators, many of whom were deeply affected at the obduracy of his conduct.”

CHAPTER LIII

Execution for treason – Burying a suicide at the junction of a cross-road – Supposed last such burial in London – The Prisons – List, and description of them – Bow Street Police Office – Expense of the Police and Magistracy – Number of watchmen, &c., in 1804 – The poor, and provision for them – Educational establishments.

BUT OF ALL brutal sentences, that for the crime of high treason, was the worst. When Colonel Despard was sentenced to death for conspiracy, on the 9th of February, 1802, the words used by the Judge, were as follow: —

“The only thing now remaining for me, is the painful task of pronouncing against you, and each of you, the awful sentence which the law denounces against your crime, which is, that you, and each of you (here his lordship named the prisoners severally), be taken to the place from whence you came, and from thence you are to be drawn on hurdles to the place of Execution, where you are to be hanged by the neck, but not until you are dead; for while you are still living, your bodies are to be taken down, your bowels torn out, and burnt before your faces! your heads are to be then cut off, and your bodies divided each into four quarters, and your heads and quarters to be then at the King’s disposal; and may the Almighty God have mercy on your Souls.”

In this case the disembowelling and dismemberment were remitted, but they were dragged to the place of execution on a hurdle, which, in this instance, was the body of a small cart, on which two trusses of clean straw were laid. They were hanged, and after hanging for about twenty-five minutes, “till they were quite dead,” they were cut down. “Colonel76 Despard was first cut down, his body placed upon saw dust, and his head on a block. After his coat had been taken off, his head was severed from his body. The executioner then took the head by the hair, and carrying it to the edge of the parapet on the right hand, held it up to the view of the populace, and exclaimed, “This is the head of a traitor – Edward Marcus Despard!.. The bodies were then put into their different shells, and are to be delivered to their friends for interment.”

Another relic of barbarism was the driving a stake through the body of a suicide, and burying him at the junction of a cross road —Morning Post, April 27, 1810: “The Officers appointed to execute the ceremony of driving a stake through the dead body of James Cowling, a deserter from the London Militia, who deprived himself of existence, by cutting his throat, at a public-house in Gilbert Street, Clare Market, in consequence of which, the Coroner’s Jury found a verdict of Self-murder, very properly delayed the business until twelve o’clock on Wednesday night, when the deceased was buried in the cross roads at the end of Blackmoor Street, Clare Market.”

The motive for this practice was, that by fastening the body to the ground, by means of a stake, it rendered it “of the earth, earthy,” and thus prevented its perturbed spirit from wandering about. It is believed that the last burial of a suicide in London, at a cross road, was in June, 1823, when a man, named Griffiths, was buried about half-past one a.m., at the junction of Eaton Street, Grosvenor Place, and the King’s Road, but no stake was driven through the body.

The Prisons in London were fairly numerous, but several of them were for debtors, whose case was very evil. There they languished, many in the most abject poverty, for years, trusting to the charity of individuals, or to funds either bequeathed, or set aside, for bettering their condition. In 1804, an Act was passed (44 Geo. III. cap. 108, afterwards repealed by the Stat. Law. Rev. Act, 1872) for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors, and they were not slow in taking advantage of it. Not only had they poverty, and loss of liberty, to contend with, but gaol fever, which carried them off at times, and cleared the prisons. So contagious was it, that in February, 1805, almost all the cadets at Woolwich suffered from it, and several died. It was imported into the school, by one of the cadets, who had been to visit some prison.

The prisons were as follow, in 1805: —

1. King’s Bench Prison, for debtors on process or execution, and for persons under sentence for misdemeanour, &c. This was in St. George’s Fields, Southwark, and was considered more wholesome than the London prisons. There were districts surrounding the prison both here, and at the Fleet, where prisoners could dwell, without going inside, by payment of fees. The prisoners inside the King’s Bench, could but obtain leave to go out once every term, or four times a year. There were 300 rooms in the prison, but it was always full, and decent accommodation was even more expensive to obtain, than at the Fleet.

2. The Fleet Prison was one belonging to the Courts of Common Pleas, and Chancery, to which debtors might remove themselves from any other prison, at the expense of six or seven pounds. A contemporary account says:

“It contains 125 rooms, besides a common kitchen, coffee and tap rooms, but the number of prisoners is generally so great, that two, or even three, persons are obliged to submit to the shocking inconvenience of living in one small room!! Those who can afford it, pay their companion to chum off, and thus have a room to themselves. Each person so paid off, receives four shillings a week. The prisoner pays one shilling and threepence a week for his room without furniture, and an additional sevenpence for furniture. Matters are sometimes so managed, that a room costs the needy and distressed prisoner from ten to thirteen shillings a week.

“Those who have trades that can be carried on in a room, generally work, and some gain more than they would out of doors, after they become acquainted with the ways of the place. During the quarterly terms,77 when the court sits, prisoners, on paying five shillings a day, and on giving security, are allowed to go out when they please, and there is a certain space round the prison, called the rules, in which prisoners may live, on furnishing two good securities to the warden for their debt, and on paying about 3 per cent. on the amount of their debts to the warden. The rules extend only from Fleet Market to the London Coffee House, and from Ludgate Hill to Fleet Lane, so that lodgings are bad, and very dear. Within the walls there is a yard for walking in, and a good racquet ground.”

3. Ludgate Prison, or Giltspur Street Compter, for debtors who were freemen of the City of London.

4. Poultry Compter – a dark, small, ill-aired dungeon – used as a House of Detention.

5. Newgate – which was the gaol both for Criminals, and Debtors, for the County of Middlesex. On the debtors’ side, the overcrowding was something terrible. The felons’, or State side, as it was called, was far more comfortable, and the criminals better accommodated. The prison might, then, be visited on payment of two or three shillings to the turnkeys, and giving away a few more to the most distressed debtors.

6. The New Prison, Clerkenwell, was also a gaol for the County of Middlesex, and was built in 1775. The fare here was very meagre – only a pound of bread a day.

7. Prison for the liberty of the Tower of London, Wellclose Square.

8. Whitechapel Prison, for debtors in actions in the Five Pounds Courts, or the Court of the Manor of Stepney.

9. The Savoy Prison, used as a Military prison, principally for deserters.

10. Horsemonger Lane Gaol, the County prison for Surrey.

11. The Clink, a small debtors prison in Southwark.

12. The Marshalsea Gaol, in Southwark, for pirates.

13. The House of Correction, Cold Bath Fields, which was built according to a plan of Howard, the philanthropist, on the basis of solitary confinement. At this time it was dreaded as a place of punishment, and went by the name of the Bastille. (Its slang name now is the Steel.)

The prisoners were not too well fed. A pound of bread, and twopenny worth of meat a day, and a very fair amount of work to do – was not calculated to make it popular among the criminal classes.

It was the only prison in which the inmates wore uniform. That of the men was blue jacket and trousers, with yellow stockings, whilst the women had a blue jacket and blue petticoat. They had clean linen every week; so that, probably, it was a healthy prison. One good thing about it was, that a portion of the prisoners’ earnings was reserved, and given to them when they quitted prison.

14. City Bridewell, Blackfriars, was a house of Correction for the City.

15. Tothill Fields, Bridewell, was a similar institution for Westminster.

16. New Bridewell, Southwark, for Surrey.

Besides these public prisons, were several private establishments used as provisional prisons – kept by the Sheriffs Officers, called lock-up, or, sponging houses, where for twelve, or fourteen shillings a day, a debtor might remain, either until he found the means to repay the debt, or it was necessary to go to a public prison, when the writ against him became returnable. They were nests of extortion and robbery.

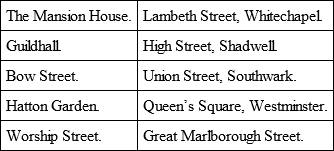

The Police Offices in London were:

Wapping New Stairs, for offences committed on the Thames. Of those extra the City, Bow Street was the chief, and the head magistrate there, was called the Chief Magistrate, and received a stipend of £1,000 per annum; a large sum in those days. He was assisted by two others, at a salary of £500 each.

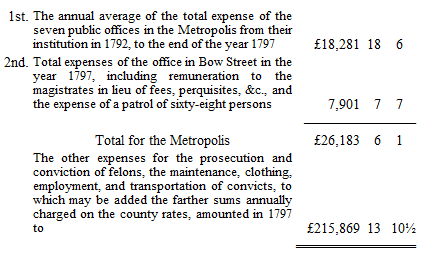

Dr. Patrick Colquhoun called so much attention to the inefficiency of the police, that a Committee of the House of Commons, in the session of 1798, sifted the matter, and from the report of this Committee, only, can we gather the criminal statistics of the kingdom (at least with regard to its expense).

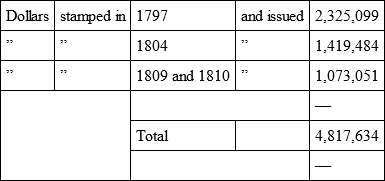

The amount of the general expense of the criminal police of the kingdom, is stated by the Committee as follows:

In 1804, it was estimated that there were 2,044 beadles and watchmen, and 38 patrols, on nightly duty in, and around the Metropolis. Of these, the City proper, with its 25 wards, contributed 765 watchmen, and 38 patrols.

The poor were pretty well taken care of. Besides the parochial workhouses, there were 107 endowed almshouses, and many other like institutions; the City Companies, it was computed, giving upwards of £75,000, yearly, away in charity. There were very many institutions for charitable, and humane purposes – mostly founded during the previous century – for the relief of widows and orphans, deaf and dumb persons, lunatics, relief of small debtors, the blind, the industrious poor, &c. And there were 1,600 Friendly Societies in the Metropolis, and its vicinity, enrolled under the Act, 33 George III. cap. 54. These had 80,000 members, and their average payments were £1 each per annum.

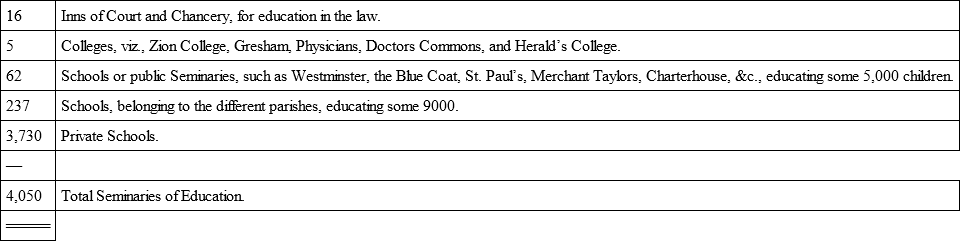

For education in London, there were:

This does not include nearly twenty educational establishments such as the Orphan Working School, the Marine Society, Freemasons School, &c.

And there were about the same number of Religious and Moral Societies, such as the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, Religious Tract Society, Missionary Societies, &c.; besides a number of Sunday Schools – so that we see education, and philanthropy, were hard at work in the Dawn of the Nineteenth Century.

THE ENDFOOTNOTES:

16(00) is a leap year.

17(00), 18(00), 19(00), are not leap years.

20(00) is a leap year.

The shifting of days caused great disturbance in festivals dependent on Easter. Pope Gregory, in 1582, ordered the 5th of October to be called 15th of October; the Low Countries made 15th of December 25th of December. Spain, Portugal, and part of Italy, accepted the Gregorian change, but the Protestant countries and communities resisted up to 1700. In England the ten days’ difference had increased to eleven days, and the Act of 24 Geo. II. was passed to equalize the style in Great Britain and Ireland to the method now in use in all Christian countries, except Russia. In England, Wednesday, September 2, 1752, was followed by Thursday the 14th of September, and the New Style date of Easter-day came into use in 1753. —Note by John Westby Gibson, Esq., LL.D.]

“WEST END GAMBLING HOUSES.

“TO THE EDITOR OF THE GLOBE.

Sir, – Can it be true – as rumour has it – that in an old-established gambling club, not 100 miles from St. James’s Street, enormous sums are nightly staked, and that fortunes rapidly change hands? I hear that three men sat down a few nights ago to play écarté in this said club, and that one of their number was at a certain period of the evening a loser of the enormous sum of £100,000. That when this very impossible figure was reduced to limits within which the winners considered the loser could pay, play ceased and the party broke up. The next day – so runs the story – one of the winners called with bills to the amount of £26,000, drawn on stamped paper, for the loser to accept. This gentleman, however, though he freely admits having played, states that, having dined not wisely but too well, he has no sort of recollection of losing any specific sum, but merely a hazy idea that fabulously large amounts were recklessly staked all round, and no accounts kept. In other words, he repudiates, and finally, after a lengthened discussion, has consented to place himself in the hands of a friend to decide what he is to pay. If this is true, and I have no reason to doubt it, I can only stigmatize the whole affair as a public scandal, and the police should promptly interfere and shut up a club where such disgraceful things occur. When Jenks’s baccarat ‘hell’ was closed, and Mr. J. Campbell Wilkinson and his six associates were each fined £500 (hence the very excellent bon mot which appeared in the Sporting Times that ‘Jenks’ babies’ had become ‘Jenks’ monkeys’), the public were justified in believing that, at last, there was not to be one law for the rich and another for the poor, and that in future men who broke the law by gambling for thousands, would have the same justice meted out to them as those who did so by tossing for coppers. However, it appears such hopes were premature, and before this happy state of things is arrived at, further attention must be drawn to the matter, hence this letter, for which I sincerely trust you will be able to find space. – I am, Sir, yours, &c.,

“A Hater of Professional Gamblers.

“January 24th.”

“Ye Captains and ye Colonels, ye parsons wanting place,

Advice I’ll give you gratis, and think upon your case,

If there’s any possibility, for you I’ll raise the dust,

But then you must excuse me, if I serve myself the first.”

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Dawn of the XIXth Century in

England, by John Ashton

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DAWN OF XIXTH CENTURY IN ENGLAND ***

***** This file should be named 49406-h.htm or 49406-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/9/4/0/49406/

Produced by Giovanni Fini, Chris Curnow and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Updated editions will replace the previous one-the old editions will be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given away-you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at www.gutenberg.org/license.