Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

They were always holding Volunteer reviews, and having Volunteer dinners, and Volunteers, generally, were raised to the rank, at least, of demigods – they were the saviours of their country. Never was there such bravery as that of these fire-eaters: and, if Boney dared show his nose on English soil – why – every British Volunteer would, individually, capture him! Volunteering even made them moral, and religious —teste the Times, September 3, 1803: “Since the formation of Volunteer Corps, the very manners of many have taken a more moral turn: public-houses are deserted for the drill, our churches are better frequented, profane swearing is banished, every man looks to his character, respects the Corps in which he is enrolled, and is cautious in all he says or does, lest he should disgrace the name of a British Volunteer.”

There was a large Patriotic Fund got up, which on December 31, 1803, amounted in Consols to £21,000, and in Money, to £153,982 5s. 7d., and it must be remembered that the taxes were very heavy. But there is an individual case of patriotism I cannot help chronicling, it is so typical of the predominant feeling of that time, that a man, and his goods, belonged to his country, and should be at his country’s disposal. Times, September 6, 1803: “A Mr. Miller,73 of Dalswinton, in Scotland, has written a letter to the Deputy Lieutenants of the County wherein he resides, in which he says: ‘I wish to insure my property, my share in the British Constitution, my family, myself, and my religion, against the French Invasion. As a premium, I offer to clothe and arm with pikes one hundred Volunteers, to be raised in this, or any of the neighbouring parishes, and to furnish them with three light field pieces ready for service. This way of arming, I consider superior with infantry, whether for attack or defence, to that now in use; but as to this, Government must determine. I am too old and infirm to march with these men, but I desire my eldest son to do so. He was ten years a soldier in the Foot and Horse service. In case of an invasion, I will be ready to furnish, when requested, 20 horses, 16 carts, and 16 drivers; and Government may command all my crops of hay, straw, and grain, which I estimate at 16,700 stones of hay, 14 lbs. to the stone, 14,000 bushels of pease, 5,000 bushels of oats, 3,080 bushels of barley.’”

CHAPTER L

The Clarke Scandal – Biography of Mrs. Clarke – Her levées – Her scale of prices for preferments – Commission of the House of Commons – Exculpation of the Duke of York – His resignation – Open sale of places – Caution thereon – Duels – That between Colonel Montgomery and Captain Macnamara.

IT WOULD be utterly impossible, whilst writing of things military, of this part of the century, to ignore the Clarke Scandal – it is a portion of the history of the times.

Mrs. Mary Ann Clarke was of humble parentage, of a lively and sprightly temperament, and of decidedly lax morality. She had married a stonemason named Clarke, who became bankrupt; she, however, cleaved to him and his altered fortunes, until his scandalous mode of living induced her to separate from him, and seek a livelihood as best she might. Her personal attractions, and lively disposition, soon attracted men’s notice, and after some time she went upon the stage, where she essayed the rôle of Portia. There must have been some fascination about her, for each of her various lovers rose higher in the social scale, until, at last, she became the mistress of the Duke of York, and was installed in a mansion in Gloucester Place. Here the establishment consisted of upwards of twenty servants. The furniture is described as having been most magnificent. The pier glasses cost from 400 to 500 pounds each, and her wine glasses, which cost upwards of two guineas apiece, sold afterwards, by public auction, for a guinea each.

She kept two carriages, and from eight to ten horses, and had an elegant mansion at Weybridge, the dimensions of which may be guessed, by the fact that the oil cloth for the hall cost fifty pounds. The furniture of the kitchen at Gloucester Place cost upwards of two thousand pounds.

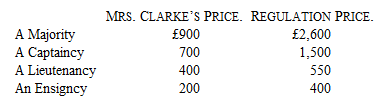

These things swallowed up a great deal of money, and, although the Duke had a fine income, yet he had the capacity for spending it; nor only so – could contract debts with great facility, so that the money which he nominally allowed Mrs. Clarke (for it was not always paid), was insufficient to provide for such extravagance, and other means had to be found. This was done by her using the influence she possessed over the Duke, and getting him to grant commissions in the army, for which the recipients paid Mrs. Clarke a lower price than the regulation scale. The satirical prints relating to her are most numerous. I only reproduce two. Her levée was supposed not only to be attended by military men, but by the clergy; and it was alleged that applications had been made through her both for a bishopric, and a deanery, and that she had procured for Dr. O’Meara, the privilege of preaching before Royalty. But it was chiefly in the sale of army commissions that she dealt, thus causing young officers to be promoted “over the heads” of veterans. Certainly her scale of prices, compared with those of the regulation, were very tempting, resulting in a great saving to the recipient of the commission.

I have no wish to go into the minute details of this scandal, but on January 27, 1809, G. Lloyd Wardell,74 Esq., M.P. for Oakhampton, began his indictment of the Duke of York, in this matter, before the House of Commons; and he showed that every sale effected through Mrs. Clarke’s means, was a robbery of the Half Pay Fund, and he asked for a Parliamentary Committee to investigate the affair; this was granted, and Mrs. Clarke, and very numerous witnesses were examined. The lady was perfectly self-possessed, and able to take care of herself; and the evidence, all through, was most damaging to the Duke. Mrs. Clarke is thus described in the Morning Post of Friday, February 3, 1809: “Mrs. Clarke, when she appeared before the House of Commons, on Wednesday, was dressed as if she had been going to an evening party, in a light blue silk gown and coat, edged with white fur, and a white muff. On her head she wore a white cap, or veil, which at no time was let down over her face. In size she is rather small, and does not seem to be particularly well made. She has a fair, smooth skin, and lively blue eyes, but her features are not handsome. Her nose is rather short and turning up, and her teeth are very indifferent; yet she has the appearance of great vivacity of manners, but is said not to be a well-bred or accomplished woman. She appears to be about thirty-five years of age.”

The Duke took the extraordinary course of writing a letter to the Speaker of the House of Commons, whilst the matter was sub judice, in which he asserted his innocence; and, foreseeing what was to follow, gave out that for the future he meant to be a very good boy, and that he would retrench in his expenditure, in order to attempt to liquidate his debts.

The House eventually found that there was nothing in the evidence to prove personal corruption, or criminal connivance on the part of His Royal Highness; but, although thus partially whitewashed, the public opinion against him was too strong, and he placed his resignation, as Commander in Chief, in the King’s hands.

Places were openly bought and sold, although it was known to be illegal, such advertisements as the following being common —Morning Post, June 14, 1800:

“Public Offices“A Young Man of good Connections, well educated in writing and accounts, and can find security, wishes for a Clerkship in any of the Public Offices. Any Lady or Gentleman having interest to procure such a situation, will be presented with the full value of the place. The greatest secrecy and honour will be observed.”

So common were they, that it was found necessary to issue notices on the subject. Here is one:

“Custom House, London, December 7, 1802.“Whereas Advertisements have, at different times, appeared in the Newspapers, offering Sums of Money for the procuring of Places, or Situations, in the Customs, inserted either by persons not aware of the serious consequences which attach upon transactions of this nature, or by persons of a different description, with a view to delude the ignorant, and unwary: The Commissioners of His Majesty’s Customs think it necessary to have it generally made known that, in addition to the punishment which the Common Law would inflict upon the offence of bribing, or attempting to bribe, any person entrusted with the disposal of any Office, the Statute passed in the fifth and sixth year of the reign of King Edward the Sixth, inflicts the penalty of incapacity to hold such office in the person purchasing, and the forfeiture of office in the person selling; and that in case any such place or situation, either shall have been, or shall hereafter be procured, or obtained, by such Corrupt means, they are determined to enforce the penalties of the Law, and to prosecute the offenders with the utmost severity. And they do hereby promise a Reward of One Hundred Pounds, to any person or persons who will give information and satisfactory proof, of any place or situation in the Customs being so obtained, so that the parties concerned therein may be proceeded against accordingly.”

Duels were most frequent, so much so, as not to excite any interest in the student of history of that time, for it is difficult to pick up a newspaper and not find one recorded. The reasons are not always given, but it did not take much to get up a duel; any excuse would serve. As an example, let us take the duel between Colonel Montgomery, and Captain Macnamara, at Chalk Farm (April, 1803) in which the former was killed, and the latter wounded. Lord Burghersh, in giving evidence before the coroner’s jury, said: “On coming out of St. James’s Park on Wednesday afternoon, he saw a number of horsemen, and Colonel Montgomery among them; he rode up to him; at that time, he was about twenty yards from the railing next to Hyde Park Gate. On one side of Colonel Montgomery was a gentleman on horseback, whom he believed was Captain Macnamara. The first words he heard were uttered by Colonel Montgomery, who said: ‘Well, Sir, and I will repeat what I said, if your dog attacks mine, I will knock him down.’ To this, Captain Macnamara replied, ‘Well, Sir, but I conceive the language you hold is arrogant, and not to be pardoned.’ Colonel Montgomery said: ‘This is not a proper place to argue the matter; if you feel yourself injured, and wish for satisfaction, you know where to find me.’” And so these two poor fools met, and one was killed – all because two dogs fought, and their masters could not keep their temper!

CHAPTER LI

Police – Dr. Colquhoun’s book – The old Watchmen – Their inadequacy admitted – Description of them – Constables – “First new mode of robbing in 1800” – Robbery in the House of Lords – Whipping – Severe sentence – The Stocks – The Pillory – Severe punishment – Another instance.

THE POLICE authorities very seldom attempted to interfere with these duels; indeed, practically there was no police. There were some men attached to the different police courts, and there were the parochial constables with their watchmen; but, according to our ideas, they were the merest apology for a police. Indeed, our grandfathers thought so themselves, and Dr. Colquhoun wrote a book upon the inefficiency of the police, which made a great stir. It was felt that some better protection was needed, as may be seen from two contemporary accounts: “Two things in London that fill the mind of the intelligent observer with the most delight, are the slight restraints of the police, and the general good order. A few old men armed with a staff, a rattle, and a lantern, called watchmen, are the only guard throughout the night against depredation; and a few magistrates and police officers the only persons whose employment it is to detect and punish depredators; yet we venture to assert that no city, in proportion to its trade, luxury, and population, is so free from danger, or from depredations, open or concealed, on property.”

“The streets of London are better paved, and better lighted than those of any metropolis in Europe; we have fewer street robberies, and scarcely ever a midnight assassination. Yet it is singular, where the police is so ably regulated, that the watchmen, our guardians of the night, are, generally, old decrepit men, who have scarcely strength to use the alarum which is their signal of distress in cases of emergency.”

Thus we see that even contemporaries were not enthusiastic over their protectors; and a glance at the two accompanying illustrations fully justify their opinion. “The Microcosm of London,” from which they are taken, says: “The watch is a parochial establishment supported by a parochial rate, and subject to the jurisdiction of the magistrates: it is necessary to the peace and security of the Metropolis, and is of considerable utility: but that it might be rendered much more useful, cannot be denied. That the watch should consist of able-bodied men, is, we presume, essential to the complete design of its institution, as it forms a part of its legal description: but that the watchmen are persons of this character, experience will not vouch; and why they are so frequently chosen from among the aged, and incapable, must be answered by those who make the choice. In the early part of the last century, an halbert was their weapon; it was then changed into a long staff; but the great coat and the lantern are now accompanied with more advantageous implements of duty – a bludgeon, and a rattle. It is almost superfluous to add, that the watch-house is a place where the appointed watchmen assemble to be accoutred for their nocturnal rounds, under the direction of a Constable, whose duty, being taken by rotation, enjoys the title of Constable of the night. It is also the receptacle for such unfortunate persons as are apprehended by the watch, and where they remain in custody till they can be conducted to the tribunal of a police office, for the examination of the magistrate.

The following little anecdote further illustrates the inefficiency of these guardians of the peace —Morning Herald, October 30, 1802: “It is said that a man who presented himself for the office of watchman to a parish at the West-end of the town, very much infested by depredators, was lately turned away from the vestry with this reprimand: ‘I am astonished at the impudence of such a great, sturdy, strong fellow as you, being so idle as to apply for a Watchman’s situation, when you are capable of labour!’”

Part of their duty was to go their rounds once every hour, calling out the time, and the state of the weather, and this was done to insure their watchfulness, but it must also have given warning to thieves. This duty done, they retired to a somewhat roomy sentry box, where, should they fall asleep, it was a favourite trick of the mad wags of the town to overturn them face downwards. Being old and infirm, they naturally became the butts and prey of the bucks, and bloods, in their nocturnal rambles; but such injuries as they received, either to their dignity, or persons were generally compounded for by a pecuniary recompense.

The Constable, was a superior being, he was the Dogberry, and was armed with a long staff.

Crime then was very much what it is now; there is very little new under the sun in wickedness – still, the Morning Post of February 3, 1800, has the

“First new mode of Robbingin 1800“A few days past, a man entered a little public-house, near Kingston, called for a pint of ale, drank it, and, whilst his host was away, put the pot in his pocket, and, without even paying for the beer, withdrew. The landlord, returning, two other men, who were in the room, asked him whether he knew the person who had just left the house? ‘No,’ he replied. ‘Did he pay for the ale?’ said they. ‘No,’ answered the other. ‘Why, d – n him,’ cried one of the guests, ‘he put the pot in his pocket.’ ‘The devil, he did!’ exclaimed the host, ‘I will soon be after him.’

“Saying this, he ran to the door, and the two men with him. ‘There, there, he’s going round the corner now!’ said one, pointing. Upon which the landlord immediately set off, and, cutting across a field, quickly came up to him. ‘Holloa! my friend,’ said he, ‘you forgot to pay for your beer.’ ‘Yes,’ replied the other, ‘I know that!’ ‘And, perhaps you know, too,’ added the host, ‘that you took away the pot? Come, come, I must have that back again, at any rate.’ ‘Well, well,’ said the man, and put his hand into his pocket, as if about to return the pot; but, instead of that, he produced a pistol, and robbed the ale-house keeper of his watch and money.

“This might seem calamity enough for the poor man; but, to fill up his cup of misfortune to the brim, he found, on reaching his home, that the two he had left behind, had, during his absence, plundered his till, stolen his silver spoons, and decamped.”

One of the most audacious robberies of those ten years, was one which took place on September 21, 1801, when the House of Lords was robbed of all the gold lace, and the ornaments of the throne, the King’s arms excepted, were stripped, and carried away. Nor was the thief ever found.

For minor offences the punishments were, Whipping, the Stocks, and the Pillory; for graver ones, Imprisonment, Transportation, and Death.

As a specimen of the offence for which Whipping was prescribed, and the whipping itself, take the following —Morning Post, November 4, 1800: “This day, being hay-market day at Whitechapel, John Butler, pursuant to his sentence at the last General Quarter Sessions, held at Clerkenwell, is to be publicly whipped from Whitechapel Bars, to the further end of Mile End, Town, the distance of two miles, for having received several trusses of hay, knowing them to have been stolen, and for which he gave an inferior price.”

The Stocks were only for pitiful rogues and vagabonds, and for very minor offences; but the Pillory, when the criminals were well known, and the crime an heinous one, must have been a very severe punishment; for, setting aside the acute sense of shame which such publicity must have awoke in any heart not absolutely callous, the physical pain, if the mob was ill-tempered, must have been great. As a proof, I will give two instances.

The first is from the Morning Herald, January 28, 1804: “The enormity of Thomas Scott’s offence, in endeavouring to accuse Capt. Kennah, a respectable officer, together with his servant, of robbery, having attracted much public notice, his conviction, that followed the attempt, could not but be gratifying to all lovers of justice. Yesterday, the culprit underwent a part of his punishment; he was placed in the pillory, at Charing Cross, for one hour. On his first appearance, he was greeted by a large mob, with a discharge of small shot, such as rotten eggs, filth, and dirt from the streets, which was followed up by dead cats, rats, &c., which had been collected in the vicinity of the Metropolis by the boys in the morning. When he was taken away to Cold Bath Fields, to which place he is sentenced for twelve months, the mob broke the windows of the coach, and would have proceeded to violence75 had the Police Officers not been at hand.”

The other is taken from the Annual Register, September 27, 1810: “Cooke, the publican of the Swan, in Vere Street, Clare Market, and five others of the eleven miscreants convicted of detestable practices, stood in the pillory in the Haymarket, opposite to Panton Street. Such was the degree of popular indignation excited against these wretches, and such the general eagerness to witness their punishment that by ten in the morning, all the windows and even the roofs of the houses were crowded with persons of both sexes; and every coach, waggon, hay-cart, dray, and other vehicle which blocked up great part of the streets, were crowded with spectators.

“The Sheriffs, attended by the two City marshals, with an immense number of constables, accompanied the procession of the prisoners from Newgate, whence they set out in the transport caravan, and proceeded through Fleet Street and the Strand; and the prisoners were hooted and pelted the whole way by the populace. At one o’clock, four of the culprits were fixed in the pillory, erected for, and accommodated to, the occasion, with two additional wings, one being allotted to each criminal. Immediately a new torrent of popular vengeance poured upon them from all sides; blood, garbage, and ordure from the slaughter houses, diversified with dead cats, turnips, potatoes, addled eggs, and other missiles to the last moment.

“Two wings of the pillory were then taken off to place Cooke and Amos in, who, although they came in only for the second course, had no reason to complain of short allowance. The vengeance of the crowd pursued them back to Newgate, and the caravan was filled with mud and ordure.

“No interference from the Sheriffs and police officers could restrain the popular rage; but, notwithstanding the immensity of the multitude, no accident of any note occurred.”

CHAPTER LII

Smuggling – An exciting smuggling adventure – The Brighton fishermen and the Excise – “Body-snatching” – “Benefit of Clergy” – Tyburn tickets – Death the penalty for many crimes – “Last dying Speech” – The “condemned pew” at Newgate – Horrible execution at Jersey – The new drop – An impenitent criminal.

THE OFFENCE of Smuggling, now all but died out, was common enough, and people in very good positions in life thought it no harm to, at least, indirectly participate in it. The feats of smugglers were of such every-day occurrence, that they were seldom recorded in the papers, unless there were some peculiar circumstances about them, such as shooting an excise man, or the like. In one paper, however, the Morning Post, September 3, 1801, there are two cases, one only of which I shall transcribe. “A singular circumstance occurred on Tuesday last, at King Harry Passage, Cornwall. A smuggler, with two ankers of brandy on the horse under him, was discovered by an exciseman, also on horseback, on the road leading to the Passage. The smuggler immediately rode off at full speed, pursued by the officer, who pressed so close upon him, that, after rushing down the steep hill to the Passage, with the greatest rapidity, he plunged his horse into the water, and attempted to gain the opposite shore. The horse had not swam half way over, before, exhausted with fatigue, and the load on his back, he was on the point of sinking, when the intrepid rider slid from his back, and, with his knife, cut the slings of the ankers, and swam alongside his horse, exerting himself to keep his head above water, but all to no purpose; the horse was drowned, and the man, with difficulty, reached the shore. The less mettlesome exciseman had halted on the shore, where he surveyed the ineffectual struggle, and, afterwards, with the help of the ferryman, got possession of the ankers.”

Sometimes it was done wholesale, see the Morning Herald, February 17, 1802: “Last Thursday morning, the Brighton fishermen picked up at sea, and brought to shore, at that place, upwards of five hundred casks of Contraband spirits, of which the Revenue officers soon got scent, and proceeded, very actively, to unburden the fishermen. This landing and seizing continued, with little intermission, from six to ten, to the great amusement of upwards of two thousand people, who had became spectators of the scene. When the officers had loaded themselves with as many tubs as they could carry, the fishermen, in spite of their assiduity, found means to convey away as many more, and by that means seemed to make a pretty equal division. The above spirits, it appeared, had been thrown overboard by the crew of a smuggling vessel, when closely chased by a Revenue Cutter.”

We may claim that one detestable offence, then rife, is now extinct. I allude to “Body-snatching.” It is true that anatomists had, legally, no way of procuring subjects to practise on, other than those criminals who had been executed, and their bodies not claimed by their friends; but, although the instances on record are, unfortunately numerous, I have already written of them in another book, and once is quite sufficient.