Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

Robert Smirke, R.A., then living in Charlotte Street, was a painter of English genre pictures, and was very fond of painting scenes from Don Quixote. Sir David Wilkie, however, painted genre subjects inimitably, and stood pre-eminent in this branch of art, at the period of which I write.

Sir William Beechey was a respectable portrait painter, and filled that office to Her Majesty Queen Charlotte, but he was not a Sir Joshua. He then lived at Great George Street, Hanover Square; but he died at Hampstead, in 1839, at a good old age of over eighty. John Hoppner, R.A., was another portrait painter of the time, as was also Sir Martin Archer Shee, President R.A., then living in Cavendish Square.

Westall, as being an Academician, deserves a passing notice, and Reinagle, too; but neither have made a name that will live. One minor painter deserves to be mentioned, Henry Bone, the enamel painter, whose collection of his own works (valued at £10,000) was offered to the nation for £4,000, refused, and sold under the hammer for £2,000. John Singleton Copley was still alive, as was also Angelica Kauffman, nor must the name of Sir George Howland Beaumont be omitted; but he was more of an amateur than professional artist.

That erratic genius, George Morland, died in 1806, at the early age of forty-two. Fecund in producing pictures as he was, he never could have painted a tithe part of the genuine Morlands that have been before the public, and the secret of these forgeries probably lies in the fact, that his pictures, painted from such familiar models, as sheep and pigs, were so easily imitated. After his death a collection of his pictures was exhibited, and Gillray gave a very graphic sketch of it. The connoisseurs were well known. The old gentleman in the foreground looking through his reversed spectacles is Captain Baillie. Behind him, and using a spy glass, is Caleb Whiteford, a friend of Garrick. The tall stout man, nearest the wall, is said to be a Mr. Mitchell, a banker; but although I have carefully examined the ten years’ lists of bankers, I cannot find his name mentioned as a partner in any firm. And, I believe, the figure without a hat, is generally considered to be Christie the Auctioneer.

The foregoing is a tolerably correct list of the most eminent artists of the commencement of the century, many names of minor note, being of necessity, left out.

In sculptors, this decade was rich. The veteran Nollekens still worked, and continued to work, till his eighty-second year, and was then living in Mortimer Street. In Newman Street lived Thomas Banks, R.A., whose colossal statue of Achilles bewailing the loss of Briseis, is now in the hall of the British Institution. Sir Francis Chantrey, R.A., was then a young, and rising, sculptor, as yet but little known. John Flaxman, R.A., was then in his zenith, being made professor of sculpture to the Royal Academy in 1810. His successor, Sir Richard Westmacott, was made A.R.A., in 1805; and these names alone form an era of glyptic art unparalleled in English history.

Engravers, too, furnish a list of well-known names, among whom, for delicacy of work, Francis Bartolozzi probably stands pre-eminent, his engravings challenging competition at the present day. There were also Thomas Holloway, and William Sharp; but, perhaps, the most popular names – none of whom will ever rank as first-class engravers – are Gillray, Rowlandson, and Isaac and George Cruikshank. Their names were on every lip, and their works the theme of every tongue. Nor must we forget John Boydell, who was Alderman and Lord Mayor of the City of London. Not only an engraver by profession, he encouraged art, by commissioning the first artists of the day to paint pictures, which he afterwards had engraved, notably his magnificent Shakespeare, than which there is no more sumptuous English edition. On this he spent no less than £350,000, and by this expenditure of capital, and bad trade, owing to the war with France, and the stoppage of commercial relations with the Continent, he fell into debt, and was obliged to get an Act of Parliament passed to enable him to get rid of the original pictures and plates, of his Shakespeare Gallery, by a lottery, which was drawn in 1804.

Besides the Shakespeare Gallery in Pall Mall, and Alderman Boydell’s Gallery in Cheapside, there were several dealers’ collections – the chief of which was “The European Museum,” Charles Street, St. James’s Square. Here pictures, some of them good, were on sale on commission, and, to prevent its being merely a lounge, a shilling was charged for admission.

Not to be forgotten are the two Water Colour Societies – “The Exhibition of Paintings in Water Colours,” established in 1804, and located in 1808 in Bond Street. Reinagle was treasurer, and its members were Messrs. G. Barrett, J. J. Chalon, J. Christall, W. S. Gilpin, W. Havell, T. Heaphy, J. Holworthy, F. Nicholson, N. Pocock, W. H. Pyne, S. Rigaud, S. Shelley, J. Smith, J. Varley, C. Varley, and W. F. Wells. The associate members were Miss Byrne, and Messrs. J. A. Atkinson, W. Delamotte, P. S. Munn, A. Pugin, F. Stevens, and W. Turner.

The other society was started in 1808 or 1809, under the title of “The Associated Artists in Water Colours,” and their first exhibition was held at 20, Lower Brook Street, Grosvenor Square, where a picture gallery already existed.

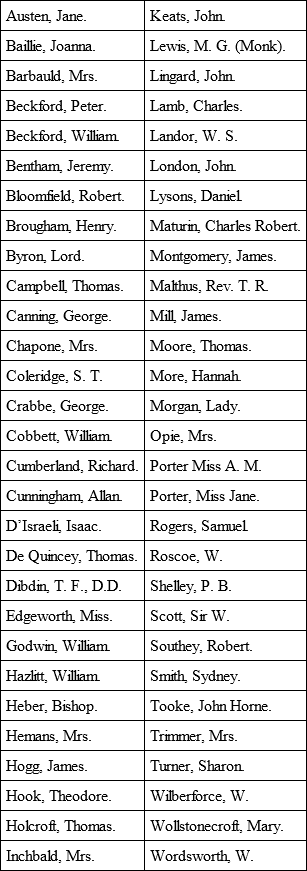

It is a thankless task to attempt to give a list of names of literary note, of this epoch, because, as in the case of foregoing lists, it is impossible to avoid giving some critic occasion to slay – an omitted name, being a heinous sin, outweighing all the patient hard work of research and reading, necessary for the writing of a book like this. Still an attempt thereat is bound to be made:

This was an age of dear books, and not of literature for the million. We are apt to think that three volumes for a novel is rather too much – when it can be, and is, afterwards, published comfortably in one; but, in those days, novels ran to four or five volumes, as may be seen by only taking one advertisement. Morning Post, July 18, 1805: “Family Annals; a Domestic Tale, in 5 Vols. 25s. by Mrs. Hunter of Norwich. The Demon of Sicily; a Romance. 4 Vols., 20s. Friar Hildargo; a Romance. 5 Vols., 25s.”

Mudie’s Library was not, but Hookham’s, and Colburn’s were in existence, and Ebers’ started in 1809.

It was a great age for the collection of first editions, unique copies, and large paper books; and, thanks to the industry, and good taste of this era, priceless treasures have been preserved to us, which might otherwise have been lost. It was a peculiarly classical age, the excavations at Pompeii, and Herculaneum, and the systematic spoliation of Etruscan tombs then going on, whetted men’s appetites, and even the Prince of Wales helped to contribute towards the stock of classical lore: “The business of unrolling the Herculaneum MSS. at Portici, under the direction of M. Hayter, and at the expense of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, proceeds with success and rapidity. One hundred and thirty MSS. have already been opened, or are unfolding, and M. Hayter hopes to be able to decypher the six hundred, which still remains in the museum. Eleven young persons are constantly employed in unrolling the MSS., and two more, in copying or drawing them. M. Hayter expects to find a Menander entire, an Ennius, and a Polybius,” &c. I give this extract merely to show the classical taste of the time.

Attention was also being aroused to Oriental literature, and the two Ouseley’s gave a great impetus to its study. Major Ouseley brought over from Bengal, in 1805, 15,000 volumes of Arabic, Persian, and Sanskrit MSS., besides a vast museum of Oriental curiosities. The Major had peculiar facilities, and opportunities, for forming his collection, as he was for some time aide de camp to the Nawab of Oude. His brother, Sir William, also possessed a choice library of some 800 Arabic, Persian, and Turkish MSS.

Not only here, but on the Continent, philology was looking up, for we find that the Pope, whilst in Paris, at the Coronation of Napoleon, visited the National Printing Office, and, as he passed along the galleries, 150 presses furnished him with a sheet each, upon which was printed the Lord’s Prayer in a different language or dialect. Asia furnished 46; Europe, 75; Africa, 12; America, 17.

In fact, literature was beginning to be aggressive, and, actually, to ask for a club of its own; and in 1808 the Alfred Club took premises in Albemarle Street, and continued its existence till 1855, when it was merged in the Oriental. It was extremely dull, and was christened by the wicked wits, the Half read; and Lord Alvanley was a member until the seventeenth Bishop saw proposed, and then he gave up.

CHAPTER XLIV

The Press —Morning Post and Times– Duty on newspapers – Rise in price – The publication of circulation to procure advertisements – Paper warfare between the Times and the Morning Post– The British Museum – Its collection, and bad arrangement – Obstacles to visitors – Rules relaxed – The Lever Museum – Its sale by lottery – Anatomical Museums of the two Hunters.

OF THE London Daily papers that were then existing, but two are now alive – the Morning Post (the Doyen of the daily press) and the Times. They were heavily taxed, in 1800, with a 3d. stamp per copy. In July, 1804, this was made 3½d.; pamphlets, half-sheet, ½d.; whole sheet, 1d.; an Almanac had to have a shilling stamp; and a perpetual Calendar, one of 10s. And this oppressive stamp, with a comparatively limited circulation, meant death to a newspaper. In 1809, the Morning Post, and other papers, boldly went in for a halfpenny rise, and gave its reasons – May 20: “Since the settlement with Government took place, which fixed the price at sixpence, every article necessary for the composition of a Newspaper, has increased in price to an unprecedented extent. Paper has risen upwards of fifty per cent.; Types upwards of eighty per cent.; Printing Ink thirty-five per cent.; Journeymen’s wages ten per cent., and everything else in the same proportion. It is therefore unnecessary for us to observe, that the advance of One Halfpenny per Paper will go but a short way towards placing the Proprietors in the same situation, in respect to profits allowed, in which they were left by the settlement of 1797; and, under all these considerations, the Public, we trust, will not deem us unreasonable in availing ourselves of the parliamentary provision that has just been made in favour of all Newspapers. The Bill will receive the Royal Assent this day, and on Monday, the Price of the Morning Post, in common with that of other Newspapers, will be Sixpence Halfpenny.”

Then, as now, the backbone of a Newspaper was its advertisements, and then also, did each Newspaper laud itself as being the best advertising medium, owing to its superior circulation. We, who are accustomed to see huge posters setting forth sworn affidavits that the daily circulation of some London newspapers amounts to some quarter of a million if not more, will feel some surprise when we learn that the Morning Post, of June 10, 1800, the then leading paper, published a sworn return (and exulted over their number and success) of 10,807 newspapers printed in the week June 2-7, or a daily average of 1,800 copies.

The World, at one time a rival, had published its circulation when it reached 1,500 daily, and thus laid claim to be considered a good advertising medium; and this was when newspapers were selling at 3d. each. In 1800 they were 6d. each, and the extra tax had diminished the circulation of the Morning Post during the previous summer by one-third, which fall they claim to have recovered, and to have raised their circulation in five years from 400 to 1,800 daily. In June, 1796, the Times published its number; and again in 1798, when it confessed to a fall of 1,400 in its daily sale.

In 1806 there was a very pretty little war as to the circulation of rival newspapers.

The Times opened the ball on the 15th of November by inserting a paragraph, “Under the Clock”: “☞We are under the necessity of requesting our Correspondents and Advertisers not to be late in their communications, if intended for the next day’s publication; as the extraordinary Sale of THE TIMES, which is decidedly superior to that of every other Morning Paper, compels us to go to press at a very early hour.”

The Morning Post, November 17th (which number is unfortunately missing in the British Museum file), challenged the statement – to which the Times replied on the 18th: “This declaration of our Sale, a Morning Paper of yesterday has thought proper to contradict, and boldly claims the superiority. We have only to say on the subject, that, if the Paper will give an attested account of its daily Sale for the last two Months, we will willingly publish it.”

And now the strife was waxing hot, for the Morning Post on the 21st of November wrote: “We admit the sale of his Paper may, for the present, be many hundreds beyond any other, except the Morning Post, the decided superiority of which, we trust, he will no longer affect to dispute… We pledge ourselves to Prove that the regular sale of the Morning Post is little short of a thousand per day superior to that of his paper.”

Of course the Times, of the 22nd of November, calls this a preposterous boast, and wishes statistics for the last two months.

Thus goaded, the Morning Post, of the 24th of November, issued affidavits from its printers and publisher, that its circulation, even at that dead season, was upwards of 4,000 daily, and that during the sitting of Parliament it reached, and exceeded 5,000, the editor remarking: “What is meant by regular Sale, is the Number which is daily served to Subscribers… If those who, by the Low Expedient of selling their Papers by the noisy nuisance of Horn Boys, take into their accounts the extra Papers so sold, it is not for us to follow so unworthy an example; to such means the Morning Post never has recourse.”

The Times, November 25th, has the last of this wordy warfare, declaring that its circulation sometimes reached 7,000 or 8,000 a day: and I should not have introduced this episode, had it not have given such a perfect insight into the working of the press of that date, which would have been unobtainable but for this quarrel.

The British Museum then stood where now it does, only Montague House, in which its treasures were then enshrined, was totally unfitted for their reception – for instance, a collection of Egyptian antiquities were kept in two sheds in the courtyard. The whole of the antiquities, and rarities, were in sad want of arrangement, and classification, and as many impediments, as possible, were placed in the way of visitors.

Take what it was like in 1802: “Persons who are desirous of seeing the Museum, must enter their name and address, and the time at which they wish to see it, in a book kept by the porter, and, upon calling again on a future day, they will be supplied with printed tickets, free of expense, as all fees are positively prohibited. The tickets only serve for the particular day and hour specified; and, if not called for the day before, are forfeited.

“The Museum is kept open every day in the week, except Saturday, and the weeks which follow Christmas day, Easter, and Whitsunday. The hours are from nine till three, except on Monday and Friday, during the months of May, June, July, and August, when the hours are only from four till eight in the afternoon.

“The spectators are allowed three hours for viewing the whole – that is, an hour for each of the three departments. One hour for the Manuscripts and Medals; one for the natural and artificial productions, and one for the printed books. Catalogues are deposited in each room, but no book must be taken down except by the officer attending, who will also restore it to its place. Children are not admitted.

“Literary characters, or any person who wishes to make use of the Museum for purposes of study and reference, may obtain permission, by applying to the trustees, or the standing committee. A room is appointed for their accommodation, in which, during the regular hours, they may have the use of any manuscript or printed book, subject to certain regulations.”

On the 8th of June, 1804, the Trustees somewhat modified the arrangements, and instead of visitors having to call twice about their tickets, before their visit, they might be admitted the day of application (Monday, Wednesday, or Friday only) subject to the following rule:

“Five Companies, of not more than 15 persons each, may be admitted in the course of the day; namely, one at each of the hours of 10, 11, 12, 1, and 2. At each of these hours the directing officer in waiting shall examine the entries in the book; and if none of the persons inscribed be exceptionable, he shall consign them to the attendant, whose turn it will be to conduct the companies through the House.

“Should more than fifteen persons inscribe their names, for a given hour, the supernumeraries will be desired to wait, or return at the next hour, when they will be admitted preferably to other applicants.”

The Museum Gardens were a great attraction, and were much visited. So much, indeed, were they thought of, that, in an advertisement of a house to let, it is stated, as a great recommendation that it commands “a view of the Museum Gardens, and a part of Hampstead Heath.”

There were other museums, notably the Leverian Museum, the collection of Sir Ashton Lever, of Alkington, near Manchester, a virtuoso of the first water. He spent very large sums on this collection, which consisted mainly of specimens of natural history (over 5,000 stuffed birds), fossils, shells, corals, a few antiquities, and the usual country museums’ quota of South Sea Island weapons, and dresses. There was much rubbish, as we should term it – according to the Gentleman’s Magazine of May, 1773 (p. 200), like a double-headed calf, a pig with eight legs, two tails, one backbone, and one head. Some pictures of birds in straw very natural, a basket of paper flowers, a head of his present Majesty, cut in Cannel Coal; a drawing of Indian ink of a head of a late Duke of Bridgwater, &c., &c.

The collection had, of course, much increased, when in 1785, Sir Ashton Lever, shortly before his death, disposed of it by lottery. The winner, Mr. Parkinson, built “a very elegant and well-disposed structure for its reception, about a hundred yards from the foot of Blackfriars Bridge, on the Surrey side.”65 The admission was one shilling. Presumably it did not pay, for it was sold by auction in 1806. The sale lasted sixty-five days. The number of lots being 7,879, and the catalogue occupying 410 octavo pages. Then there were the museums of the two Hunters – that of Dr. William Hunter, F.S.A., &c. In the period of which I treat, his anatomical specimens, coins, &c., were exhibited at the Theatre of Anatomy, in Great Windmill Street, whence, according to his will, they were after a certain time transferred to the University of Glasgow, where they now are. His brother John, who was also a F.R.S., had a grand collection of anatomical preparations, which was purchased by the Government for £15,000, and deposited, pro bono publico, in the College of Surgeons.

CHAPTER XLV

Medical – The Doctor of the old School – The rising lights – Dr. Jenner – His discovery of vaccination for smallpox – Opposition thereto – Perkins’s Metallic Tractors – The “Perkinean Institution” – His cures – Electricity and Galvanism – Galvanizing a dead criminal – Lunatic Asylums – Treatment of the insane – The Hospitals.

A PROPOS of Doctors – the medical and surgical branches of the profession were emerging from empiricism, and science was beginning to assert herself, and laying the foundation of the English School of Medicine, the finest the world has yet seen. The doctor of the old school (as given in the next page) was still extant, with his look of portentous sagacity, his Burghley-like shake of the head, his bag with instruments and medicaments, and the cane – always the gold-headed cane – which came in so useful, and gave such a look of sapience when applied to the side of the nose, affording time for consideration before giving an opinion on a doubtful case – a relic of the time when, in its gold top, was carried a febrifuge, such as aromatic vinegar, or the such like. Similar types are also given in a political caricature by Isaac Cruikshank.

But these old quacks were disappearing, and the progenitors of the present hard-working, energetic, and scientific men, our medical advisers, were arising, and I append a list, imperfect as it may be, which contains names of world-wide reputation, and thoroughly well known to every fairly educated Englishman. They are taken in no sequence, chronological or otherwise. Sir Anthony Carlisle, F.R.S., President of the Royal College of Surgeons; Sir Charles Mansfield Clarke, so famous for his treatment of the Diseases of Women and Children; Sir Astley Paston Cooper; Sir Henry Halford; that rough old bear John Abernethy; Dr. Matthews Baillie the brother of Joanna Baillie; Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie – then a young man; Dr. Edward Jenner, of whom more anon; Wm. Lawrence, F.R.S., Surgeon Extraordinary to the Queen; Sir Charles Bell, another famous Surgeon, whose “System of Anatomy,” is still a text book; Geo. James Guthrie, and many others; but a sufficient number of well-known names have been given to warrant the assertion that it was an exceptionally brilliant time of English medicine and surgery.

Perhaps the medical man of this era, to whom the whole world is most indebted, is Dr. Jenner, who thoroughly investigated the wonderfully prophylactic powers of the cow pock. He had noticed that milkers of cows could not, as a rule, be inoculated with the smallpox virus – a means of prevention then believed in, as the patient generally suffered but slightly from the inoculation, and it was then a creed, long since exploded, that smallpox could not be taken twice. This fact of their resistance to variolous inoculation set him thinking, and he came to the conclusion that they had absorbed into their systems, a counter poison in the shape of some infection taken from the cows. He made many experiments, and found that this came from a disease called the cow pock, and that the vaccine lymph could not only be taken direct from the cow, but also by transmission from the patients who had been inoculated with that lymph, and whence the present system of so-called vaccination – the greatest blessing of modern times.

Jenner, of course, was opposed; fools do not even believe in vaccination now, and great was the battle for, and against, in the medical profession, and many were the books written pro and con. “Vaccination Vindicated,” Ed. Jones; “A Reply to the Anti-Vaccinists,” Jas. Moore; “The Vaccine Contest,” Wm. Blair; “Cow Pock Vaccination,” Rowland Hill; “Birch against Vaccination,” “Willan on Vaccination,” &c., &c.

Gillray could not, of course, leave such a promising subject alone, and he perpetrated the accompanying illustration. Here Dr. Jenner (a very good likeness) is attending to his patients – vaccinating, rather too vigorously, one lady – the lymph, in unlimited quantity, being borne by a workhouse boy, and receiving his patients who are exhibiting the different phases of their vaccination. As a rule, they seem to have “taken” too well.

A quack, who flourished early in the century, far better deserved the caricaturists’ pencil than Jenner, and he got it. The illustration on this page represents an American quack, named Perkins, who pretended to cure various diseases by means of his metallic tractors – operating on John Bull. The paper on the table is the True Briton, and it reads thus: “Theatre – dead alive – Grand Exhibition in Leicester Square. Just arrived from America the Rod of Æsculapius. Perkinism in all its glory, being a certain cure for all Disorders, Red Noses, Gouty Toes, Windy Bowels, Broken Legs, Hump backs. Just discovered, Grand secret of the Philosopher’s Stone, with the true way of turning all metals into Gold.”