Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

He was presented to the Prince of Wales at Carlton House; and, on the 5th of December, 1804, when he was acting at Covent Garden, the King and the Royal Family went to Drury Lane to see the “School for Scandal,” and the King having expressed a wish to see the marvellous boy, Sheridan had him fetched, and hence the illustration of “The Introduction,” by J. B. Sheridan introduces him to the King as “The Wonder of the Theatrical World – A Diamond amongst Pebbles – A Snowdrop in a Mud-pool – The Golden Fleece of the Morning Chronicle! The Idol of the Sun! The Mirror of the Times! The Glory of the Morning Post! The Pride of the Herald! and the finest Cordial of the Publican’s Advertiser.” The young Roscius thus presented, makes his bow to the Royal Couple, saying, “Never till this hour stood I in such a presence, yet there is something in my breast which makes me bold to say that Norval ne’er will shame thy favour.”

He also visited the Duke of Clarence, and Charles James Fox; and, when he had an illness, probably induced by over excitement, and petting, so numerous were the inquiries after his precious health, that bulletins had to be issued.

At Drury Lane his first appearance was as enthusiastically received, as at Covent Garden; and, if possible, more riotously, for the mob broke all the windows within their reach, on the Vinegar Yard side of the Theatre, and, when the passages were thrown open, the balustrades, on both sides of the staircase which led to the boxes, were entirely demolished.

From 1805 to 1808, he principally played at the provincial theatres, and in the latter year, being seventeen years of age, he was entered as a gentleman Commoner of Christ’s College, Cambridge, and also was gazetted as Cornet in the North Shropshire Yeomanry Cavalry. His father died in 1811, and he then left Cambridge, residing on an estate his father had purchased, near Shrewsbury. Here he stayed till he was twenty years old, when his passion for the stage revived; and he acted, with occasional intermissions, until he was thirty-two years old, when he retired from the stage, and lived a quiet life until his death, which took place on the 24th of August, 1874.

CHAPTER XXXIX

Betty’s imitators – Miss Mudie, “The Young Roscia” – Her first appearance in London – Reception by the audience – Her fate – Ireland’s forgery of “Vortigern and Rowena” – Fires among the theatres – Destruction of Covent Garden and Drury Lane.

BETTY’S success raised up, of necessity, some imitators – there were other Roscii, who soon disappeared; and, as ladies deny the sterner sex the sole enjoyment of all the good things of this world, a Roscia sprang into existence – a Miss Mudie, who entered on her theatrical career, even earlier than Master Betty. Morning Post, July 29, 1805: “The Young Roscia of the Dublin Stage (only seven years old), who is called the Phenomenon, closed her engagement there on Monday last, in the part of Peggy, in the Country Girl, which she is stated to have pourtrayed with ‘wonderful archness, vivacity, and discrimination.’”

Children, such as this, however precocious, are, of course simply ridiculous, and we are not astonished to find fun being made of them. Says the Morning Post, October 21, 1805: “A young Lady was the other day presented by her nurse and mamma to one of our managers for an engagement. She came recommended by the testimony of an amateur, that she was a capital representative of the Widow Belmour. The manager, after looking at her from head to foot, exclaimed, ‘But how old is Miss?’ ‘Seven years old, sir, next Lammas,’ answered the nurse, ‘bless her pretty face.’ ‘Oh! Mrs. Nurse,’ replies the manager, gravely, ‘too old, too old; nothing above five years will now do for Widow Belmour.’”

Old playgoers had not quite lost all their wits, although they had been somewhat crazy on the subject of young Roscius; but he was then fourteen, whilst this baby was only seven. However, the Phenomenon appeared, and duly collapsed, the story of which I should spoil did I not give it in the original. Here it is, as a warning to ambitious débutantes—Morning Post, November 25, 1805:

“Covent Garden. The play of the Country Girl was announced at this house, on Saturday evening, for the purpose of introducing to a London audience, a very young lady, a Miss Mudie, in the character of Miss Peggy. Miss Mudie has played, as it has been reported, but we doubt the truth of the report, with great success at Dublin, Liverpool, Birmingham, &c., where she has been applauded and followed nearly as much as Master Betty. The people of London seem to have been aware that these reports were unfounded, for no great degree of curiosity prevailed to see her on Saturday.

“The audience received this child very favourably on her entrance. She is said to be ten years of age, but in size she does not look to be more than five. She is extremely diminutive, and has not the plump, comely countenance of an infant: her nose is very short; her eyes not well placed; she either wants several teeth, or is, perhaps, shedding them; and she speaks very inarticulately. It was difficult to understand what she said. When she attempts expression of countenance, her features contract about the nose, and eyes, in a way that gives reason to suppose she is older than her person denotes. She seems to have a young body with an old head.

“In the first passages of her part, she appeared to give some satisfaction, and was loudly applauded; an indulgent audience wishing, no doubt, to encourage her to display her full powers; but when she was talked of as a wife, as a mistress, and an object of love, the scene became so ridiculous that hissing and horse laughing ensued. She made her début before Miss Brunton, a tall, elegant, beautiful woman, and looked in size just as if Miss Brunton’s fan had been walking in before her; Miss Mudie the married woman, and Miss Brunton the maiden! When she was with her husband, Mr. Murray, no very tall man, she did not reach higher than his knee, and he was obliged to stoop even to lay his hand upon her head, and bend himself down double to kiss her; when she had to lay hold of his neckcloth to coax him, and pat his cheeck, he was obliged to stoop down all fours that she might reach him! The whole effect was so out of nature, so ludicrous, that the audience very soon decided against Miss Mudie. At first they did not hiss when she was on the stage, from delicacy; but, in her absence, hissed the performance, to stop the play, if possible. But as she persevered confidently they hissed her, and at last called vehemently, Off! off! Miss Mudie was not, however, without a strong party to support her; but the noise increased to that degree in the latter scenes that not a word could be heard, on which Miss Mudie walked to the front of the stage with great confidence and composure, not without some signs of indignation, and said:

“‘Ladies and Gentlemen,

“‘I know nothing I have done to offend you, and has set (sic) those who are sent here to hiss me; I will be very much obliged to you to turn them out.’

“This speech, which, no doubt had been very imprudently put into the infant’s mouth, astonished the audience; some roared out with laughter, some hissed, others called Off! off! and many applauded. Miss Mudie did not appear to be in the slightest degree chagrined or embarrassed, and she went through the scene with as much glee as if she had been completely successful. At the end of it the uproar was considerable, and a loud cry arising of Manager! Manager! Mr. Kemble came forward. In substance he said:

“‘Ladies and Gentlemen,

“‘Miss Mudie having performed at various provincial theatres with great success, her friends thought themselves authorised in presenting her before you. It is the duty, and the wish, of the proprietors of this House to please you; and to fulfil both, was their aim in bringing forward Miss Mudie. ‘The Drama’s laws, the Drama’s patrons give’ – Miss Mudie intends to withdraw herself from the stage; but I entreat you to hear her through the remainder of her part.’”

She came on the stage again, but the audience would not listen to her, and Miss Searle had to finish her part. What became of this self-possessed child I know not; according to the Morning Post, April 5, 1806, she joined a children’s troupe in Leicester Place, where, “though deservedly discountenanced at a great theatre, she will, no doubt, prove an acquisition to the infant establishment.”

Late in the last century, the literary and theatrical world had been thrown into a state of high excitement, by the announcement of the discovery of an original play by Shakespeare, called “Vortigern and Rowena,” which was acted at Drury Lane, and condemned, as spurious, the first night; but belief in it lasted for some time, and the question was of such importance, that the Morning Post, in 1802, took the suffrages of the fashionable world, as to its authenticity. The question was set at rest in 1805 by the forger himself, one William Henry Ireland, who had the audacity to publish a book55 in which he unblushingly details all his forgeries, and his method of doing them. It is an amusing volume, and has recently been utilized by a novelist.56 The absolute forgeries are still in existence, including the pseudo-lock of Shakespeare’s hair; and they changed owners some few years since, when they were sold by auction at very low prices.

There was a great fatality among theatres; there were but few of them, and they were continually being burnt down. The Opera House in 1789; The Pantheon 1792; Astley’s Amphitheatre, September 17, 1794. This theatre was unlucky. It again fell a victim to the flames, September 1, 1803; and Astley, on this occasion, seems to have met with an accident —Times, September 7, 1803: “Fortunately for Mr. Astley, almost the whole of his plate was at Lower Esher, from which place he reached the Amphitheatre in one hour and a quarter. It was not till he came to Vauxhall that his horse fell; the same presentiment which foreran the former conflagration of his property, the moment he heard the gate bell ring, he exclaimed to Mrs. Astley, ‘They come to tell me that the Theatre is on fire.’”

The Surrey Theatre, or, as it was then called, the Royal Circus, was destroyed by fire August 12, 1805; and Covent Garden was burnt down September 20, 1808 – the fire being supposed to have been caused by a piece of wadding from a gun fired during the performance of Pizarro. It was, of course, a tremendous conflagration, and unfortunately resulted in loss of life, besides the loss of many original scores of Handel, Arne, and other eminent composers, together with Handel’s organ.

Plans for a new theatre were soon got out, and Mr. Smirke (afterwards Sir Robert, to whom we owe the beautiful British Museum, and the General Post Office) was the architect. The first stone was laid, with much Masonic pomp, on the 31st of December, 1808, by the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Sussex, and a distinguished circle of guests, being present. The weather was unpropitious, but immense crowds of people were present; and it is curious to learn, as showing the defective police of the time, that “The Horse Guards patrolled the streets, and several of the Volunteer Corps did duty on the occasion.”

Within two months from the above date, Drury Lane Theatre was totally destroyed by fire. On the 24th of February, about 11 p.m., it was discovered, and it did not take long before the whole was in a blaze; not for want of precautions, for it seems they had adopted the best accepted preventitives of a great theatrical conflagration known to modern architects, viz., an iron curtain, and a huge reservoir of water on the top of the building – the latter being described as “a mere bucket full to the volume of fire on which it fell, and had no visible effect in damping it,” which may be comforting for modern playgoers to remember. Nor was it long in burning; by 5 a.m. “the flames were completely subdued” – that is, there was nothing left to burn. Very little was saved, only a bureau and some looking-glasses, from Mrs. Jordan’s dressing-room, and the “Treasury” books and some papers. Sheridan took his loss, outwardly, with great sang froid, one anecdote affirming that, on a remark being made to him that it was a wonder he could bear to witness the destruction of his property, he replied, “Why! where can a man warm himself better than at his own fire-side?” However, by his energy, he soon found temporary premises for his company, and, having obtained a special license from the Lord Chamberlain, he took the Lyceum and opened it on the 25th of September, or, within a week of the fire.

CHAPTER XL

The O. P. Riots – Causes of – Madame Catalani – Kemble’s refutation of charges – Opening of the theatre, and commencement of the riots – O. P. medals, &c. – “The house that Jack built” – A committee of examination – Their report – A reconciliation dinner – Acceptation of a compromise – “We are satisfied” – Theatre re-opens – Re-commencement of riots – The proprietors yield, and the riots end.

WE NOW come to the celebrated O. P. Riots, which find no parallel in our theatrical history, and which would require at least two thick volumes to exhaust. Never was there anything so senseless; never could people have been more persistently foolish; they would listen to no reason; they denied, or pooh-poohed, every fact.

O. P. represents “Old Prices,” and, as the management of the new theatre had raised the price of their entertainment, as they had a perfect right to do, these people demanded that only the old prices should be charged for admission. It was in vain that it was pointed out that very early notice was given of the intended rise, as indeed it was, directly after the destruction of the fire —vide Morning Post, September 24, 1808: “The Managers, we understand, intend to raise the price of admission, when they open at the Opera to 7s. for the boxes, and to 4s. for the pit. The admission for the galleries to remain as before. Much clamour has already been excited against this innovation, but we think unjustly.”

Had this been the only grumble, probably no more would have been heard of it, but all sorts of rumours got about – That the proprietors, of whom Kemble was one (and, except on the stage, he was not popular), would make a handsome profit out of the insurance, and sale of old materials; that the increased number of private boxes, with their ante-rooms, were built for the special purpose of serving as places of assignation for a debauched aristocracy; and, therefore, a virtuous public ought to rise in its wrath against them. And last, but not least, they tried to enlist patriotic feelings into the question, and appealed to the passions of the mob – (remember we were at war with the French, and the ignorant public could not discriminate much between the nationality of foreigners) as to whether it was fair to pay such enormous nightly sums to a foreigner – which sums were partly the cause of the rise in price – when native talent was going unappreciated.

This foreigner was Madame Angelica Catalani, a lady who was born at Sinigaglia, in 1779. At the early age of twelve, when at the convent of St. Lucia, at Gubbio, her beautiful voice was remarkable, and when she left the convent, at the age of fifteen, she was compelled to get a living on the stage, owing to her father’s ruin.

At sixteen, she made her début at Venice, in an opera by Nasolini; and she afterwards sang at Florence, at La Scala in Milan, at Trieste, Rome, and Naples. Her fame got her an engagement at Lisbon, where she married M. Valabrègue, a French officer attached to the Portuguese Embassy; but she still kept to her name of Catalani – at all events, on the stage. From Lisbon she went to Madrid, thence to Paris, where she only sang at concerts; and, finally, in October, 1806, she came to London, where she speedily became the rage. According to one biographer (Fétis), she gained immense sums here; but I much doubt his accuracy. He says: “In a single theatrical season which did not last more than four months, she gained about 180,000 francs (£7,200), which included her benefit. Besides that, she gained, in the same time, about 60,000 francs (£2,400) by soirées and private concerts. They gave her as much as 200 guineas for singing at Drury Lane, or Covent Garden – ‘God save the King,’ and ‘Rule, Britannia,’ and £2,000 sterling were paid her for a single musical fête.”

This, according to the scale paid her at Covent Garden, said by her opponents to be £75 per night, must be excessive; but the mob had neither sense, nor reason, in the matter; she was a foreigner, and native talent was neglected. Her name suggested a subject to the caricaturist, of which he speedily availed himself.

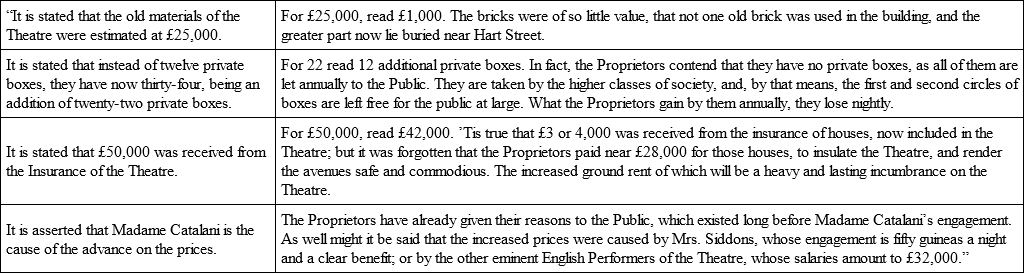

These were the principal indictments against Kemble (for he, as manager, had to bear the brunt of the riot) and the proprietors replied to them categorically —vide Morning Post, September 18, 1809:.

There was good sound sense in this refutation, yet something is wanting to explain more fully the riot which was to come, and which, at all events, was popularly supposed to relate to the structure of the building, and to the rise in prices. The following is much condensed from a contemporary account of the theatre:

“The Pit of this Theatre is very spacious… The two Galleries are comparatively small, there not being accommodation in the upper, for more than 150 or 200 persons! The Upper Gallery is divided into five compartments, and may thus be considered a tier of five boxes, with a separate door at the back of each. These doors open into a spacious lobby, one side of which is the back of the gallery, and the other the exterior wall of the Theatre, with the windows into the street. The lobby to the middle gallery beneath is similarly situated. Under the gallery is a row of private boxes, constituting the whole third tier! They consist of 26 in number, with a private room behind each. The Carpeting was laid down in these boxes on Saturday last; but the furniture of each, and also of the adjoining room, will be according to the taste of the several occupants, among whom are some of the Royal Dukes.”

And now I have to chronicle one of the most senseless phases of public opinion that ever made a page, or a paragraph, of history. The Theatre opened on September 18, 1809, with “Macbeth” and “The Quaker,” but not one word that was delivered on the stage could be heard by the audience.

When the curtain drew up, Kemble delivered an address, which was extremely classical – all about Æschylus, Thespis, and Sophocles, of which the people present knew nothing, until they saw the next morning’s papers. Instead of listening, they sang “God save the King” with all the power of their lungs, and in good order; but that once over, then, with one consent, they began to yell “No Kembles – no theatrical tyrants – no domineering Napoleons! – What! will you fight, will you faint, will you die, for a Shilling? – No imposition! – no extortion! – English charity. – Charity begins at home. – No foreigners – No Catalanis.”

Somebody in the boxes addressed the frantic mob, but nothing was heard of his speech, and a magistrate named Read, attended by several Bow Street officers, came on the stage, and produced the Riot Act; it was no good – he could not be heard, and yet, among the audience, were many men of position, and even some of the Royal Dukes.

The second night the row was as bad, and it now was becoming organized. People brought placards, which began mildly with “The Old Prices,” and afterwards developed into all sorts of curious things. One was displayed in the first circle of the boxes, and “Townsend,57 heading a posse of constables, rushed into the pit to seize this standard of sedition, together with the standard bearers. A contest ensued of the hottest kind, staffs and sticks were brandished in all directions; and, after repeated onsets and retreats, Townsend bore away a few of the standards, but failed in capturing the standard bearers. He retired with these imperfect trophies. But, as the oppositionists kept the field of battle, they claimed the victory, which they announced to the boxes and galleries with three cheers. The standard bearers in the boxes were not equally successful. They were but few in number, and not formed into a compact body, and had, besides, their rear and flanks open to the attack of the enemy. Some of them we saw seized from behind, and dragged most rudely out of the boxes, and treated, in every respect, with a rigour certainly beyond the law. One of them, who had all the appearance of a gentleman, was accompanied by a lady, who screamed at seeing the rudeness he suffered, and then flew out of the box to follow him. This vigorous activity on the part of the constables made the placards disappear for a time; but they were soon after hoisted again in the pit, and hailed with acclamations every time they were observed.”

On the third night the uproar was as great, many of the lights had been blown out, and the place was a perfect pandemonium; when Kemble, in dress suit of black, and chapeau bras, appeared, and obtained a momentary hearing. “Ladies and gentlemen,” said he, “permit me to assure you that the proprietors are most desirous to consult your wishes (loud and continued applause). I stand here, to know what you want.” If the noise and uproar could have been greater than before, it was after this brusque, and unfortunate, speech. “You know what we want – the question is insulting – Off! off! off!” For five minutes did the great man face his foes, and then he retired. Then some one in the boxes addressed the audience in a speech calculated to inflame, and augment, the riot; and Kemble once more came forward with a most sensible exposition as to the sum spent on the theatre, its appointments, and company. He might as well have spoken to the wind.

Night after night this scene of riot continued, varied only by the different noises – of bugle and tin horns, rattles, clubs, yelling, &c. – and the manifold placards, which differed each night, and were now not disturbed. There were O. P. medals struck – how many I know not – but there are three of them in the British Museum. One, which is struck both in white metal and bronze, has obv. John Bull riding an Ass (Kemble), and flogging him with two whips – Old and New Prices. Leg. FROM N TO O JACK YOU MUST GO; in exergue—

JOHN BULL’S ADVICE TO YOU, IS GO.’TIS BUT A STEP FROM N TO ORev. a P within an O, surrounded by laurel, and musical emblems. Leg. GOD SAVE THE KING; in exergue, May our rights and privileges remain unchanged. Another has obv. Kemble’s head with asses’ ears; and the third, which was struck when Mr. Clifford was being prosecuted for riot, has obv. Kemble’s head with a fool’s cap on; leg. OH! MY HEAD AITCHES; in exergue, OBSTINACY.

Then, too, the Caricaturists took up the tale and worked their wicked will upon the theme. I only reproduce one – by Isaac Cruikshank (father to George) which was published 28th September, 1809.

On the 22nd of September Kemble came forward and said, inter alia, that the proprietors, anxious that their conduct should be fully looked into, were desirous of submitting their books, and their accounts, to a committee of gentlemen of unimpeachable integrity and honour, by whose decision they would abide. Meanwhile the theatre would be closed, and Madame Catalani, cancelling her engagement, went to Ireland.

“THE DEPARTURE FOR IRELAND“When Grimalkin58 the Spy, took a peep at the house,And saw such confusion and strife,He stole to the Green-room as soft as a Mouse,And thus he address’d his dear wife:‘Mon Dieu! don’t sit purring, as if all was right,Our measure of meanness is full,We cannot stay here to be bark’d at all night,I’d rather be toss’d by a Bull.’”The committee of gentlemen (of whom the well-known John Julius Angerstein was one), published their report, and balance sheet, which was publicly advertised on the 4th of October, and they agreed that the profit to the shareholders on the capital, employed during the six years, was 6⅜ per cent. per annum, and that during that time they had paid £307,912. This, of course, would not satisfy the mob, and on the re-opening of the theatre on the 4th of October there was the same riot with its concomitant din of cat calls, rattles, horns, trumpets, bells, &c. For a few days the riot was not so bad, although it still continued; but, on the 9th of October, it broke out again, and the proprietors were compelled to take proceedings at Bow Street against some of the worst offenders. This had the effect, for a time, of stopping the horns, rattles, bells, bugles, &c., but the rioters only exchanged one noise for another, for now they imitated all the savage howlings of wild beasts, and it seemed as if Pidcock’s Menagerie had been turned into the theatre.