Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

CHAPTER XXXI

“The three Mr. Wiggins’s” – The “Crops” – Hair-powdering – The powdering closet – Cost of clothes – Economy in hats – Taxing hats – Eye-glasses – “The Green Man” at Brighton – Eccentricities in dress.

“THE THREE Mr. Wiggins’s” are real “Bond Street Loungers,” and are portraits of Lord Llandaff and his brothers, the Hon. Montagu, and George, Matthews. They were dandies of the purest water, with their white waistcoats and white satin knee-ribbons. The title is taken from a farce by Allingham, called “Mrs. Wiggins,” played at the Haymarket, May 27, 1803. It is very laughable, and turns upon the adventures of an old man named Wiggins, and three Mrs. Wiggins’s. It was very popular, and gave the title to another caricature of Gillray’s.

As will be seen, they wore powder, but this curious fashion was on its last legs – the Crops, or advanced Whigs, having given it its death blow; still, it struggled on for some years yet. There is a little story told in the Morning Herald of the 20th of June, 1804, which will bear reproduction: “The following conversation occurred on Monday last, in the Gallery of the House of Commons. A gentleman, very much powdered, happened to sit before another who did not wear any. During the course of the debate the son of powder in front, frequently annoyed, by his nodding, or rather his noddle, his neighbour in the rear, for which he apologized, as often as any notice was taken of it. At last, the influence of Morpheus became so powerful, that the rear rank man found his arm perfectly painted with powder, in such a manner as to produce some ignition in his temper, and repel his annoyer with a little more spunk46 than he showed on any of the former occasions. This being resented, the other presented his arm, and said, ‘Sir, you should not be angry; for, if I wished for such an ornament as this, I should, this morning, have left that office to my hair-dresser. I am a man of such independence that I would not, willingly, be indebted to you for a single meal, and here you have forced on me a bushel. If I had been your greatest enemy, you could do nothing more severe, than to pulverize me; and, as I have given you no intentional offence, I must beg of you, in future, not to dust my jacket.’ This sally had all the effect for which it was intended, and, instead of exchanging cards, the affair ended, like some senatorial speeches, in a laugh.”

As all the members of the family, including the domestics had to be powdered, most houses of any pretension had a small room set apart for the performance, called “the powdering room,” or closet, where the person to be operated upon went behind two curtains, and, by putting the head between the two, the body was screened from the powder, and the head received its due quantity, without injury to the clothes.

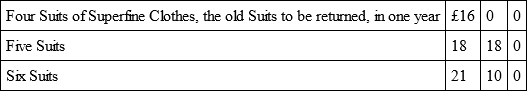

Still, all the world was not rich, and, therefore, with some, economy in clothing was a necessity. As is usual, when a want appears, it is met; and in this case it certainly was, in a (to us) novel manner —Morning Post January 12, 1805: “Interesting to the Public. W Welsford, Tailor, No. 142, Bishopsgate Street, respectfully informs the Public, that he continues to pursue the plan, originally adopted by him, six years since, of SUPPLYING CLOTHES, on the following terms: —

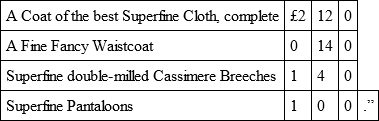

“Those Gentlemen who should not prefer the above Contract, may be supplied at the undermentioned reduced price:

Nor was this the only practical economy in dress in that age. Hats, which were then, as a rule, made of Beaver, were somewhat expensive articles; and, in looking diligently over the newspapers of the times, I found that here, again, a want arose, and was met. These Beaver hats got shabby, and could be repaired; a firm advertising that “after several years’ practice they have brought the Art of Rebeavering Old Hats to greater perfection than it is possible to conceive; indeed, they are the only persons that have brought it to perfection; for, by their method, they can make a gentleman’s old hat (apparently not worth a shilling) as good as it was when new… Gentlemen who prefer Silk hats, may have them silked, and made waterproof.”

Hats were rendered dearer than they would, otherwise, have been, by their having to pay a tax – the only portion of personal clothing which did so. This tax, of course, was evaded; so we find, in the Morning Post, May 20, 1810, the following “Caution to Hatters. A Custom prevailing among hatters, of pasting the stamp upon the lining, by which the same stamp may frequently be sold with different hats successively, they are required by the Commissioners of the Stamp Duties, to conform, in selling hats, to the provisions of the Act of the 36th of George III., cap. 125, secs. 3, 4, 7, 9, which directs that the lining, or inside covering of every hat shall, itself, be stamped; and it is the intention of the Commissioners to prosecute for the penalties of that Act, inflicted on all persons guilty of violating its regulations. Persons purchasing hats are requested to be careful in seeing that they are duly stamped upon the lining itself, and not by a separate piece of linen affixed to it; and reminded that the Act above-mentioned (sec. 10) inflicts a penalty of £10 upon persons buying, or wearing, hats not legally stamped.”

We have seen it recommended to the Bond Street Lounger that it was absolutely necessary for him to have an eye-glass suspended from his button-hole; and the same fashion is mentioned in the Morning Post, August 28, 1806: “The town has been long amused with the quizzing glasses of our modern fops, happily ridiculed by a door-key in O’Keefe’s whimsical farce of The Farmer. A Buck has lately made his appearance in Bond Street, daily, between two and four o’clock, with a Telescope, which he occasionally applies to his eye, as he has a glimpse of some object passing on the other side of the street, worth peeping at. At the present season, we cannot but recommend this practice to our fashionable readers, who remain in the Metropolis. It indicates friendship, as it shows a disposition to regard those who are at a distance.”

There have been, in all ages of fashion, some who outvied the common herd in eccentricity of costume; and the early nineteenth century was no exception to the rule. It is true that it had not, in the time of which I write, arisen to the dignity of a “pea-green Haines;” but still, it could show its “Green Man.” “Brighton, September 25, 1806. Among the personages attracting, here, public notice, is an original, or would-be original, generally known by the appellation of ‘the Green Man.’ He is dressed in green pantaloons, green waistcoat, green frock, green cravat; and his ears, whiskers, eyebrows, and chin, are better powdered than his head, which is, however, covered with flour. He eats nothing but green fruits and vegetables; has his rooms painted green, and furnished with a green sofa, green chairs, green tables, green bed, and green curtains. His gig, his livery, his portmanteau, his gloves, and his whip, are all green. With a green silk handkerchief in his hand and a large watch chain, with green seals fastened to the green buttons of his green waistcoat, he parades every day on the Steyne, and in the libraries, erect like a statue, walking, or, rather, moving to music, smiling and singing, as well contented with his own dear self, as well as all those round him, who are not few.” That he had money was evident, for his green food, including, as it did, choice fruit, would sometimes cost him a guinea a day; besides which, he was seen at every place of amusement, and spent his money lavishly. Eventually, he turned out to be a lunatic, and, after throwing himself out of windows, and off a cliff, he was taken care of.

The two preceding illustrations are manifest exaggerations of costume; but the germ of truth which supplies the satire is there; and, with them, the men’s dress of this period is closed.

CHAPTER XXXII

Ladies’ dress – French costume – Madame Recamier – The classical style – “Progress of the toilet” – False hair – Hair-dresser’s advertisement – The Royal Family and dress – Curiosities of costume.

IN LADIES’ dress more allowance must be made for the caprices of fashion; it always has been their prescriptive right to exercise their ingenuity, and fancy, in adorning their persons; and, save that the head-dress is somewhat caricatured, the next illustration gives a very good idea of the style of dress adopted by ladies at the commencement of 1800, some phases of which we are familiar with, owing to their recent reproduction – such as the décolletée dress, and clinging, and diaphonous skirt, as well as the long gloves.

However, the eccentricities of English costume, at this period, were as nothing compared with their French sisters. The Countess of Brownlow,47 speaking, as an eye-witness, says: “The Peace of 1802 brought, I suppose, many French to England; but I only remember one, the celebrated Madame Recamier, who created a sensation, partly by her beauty, but still more by her dress, which was vastly unlike the unsophisticated style, and poke bonnets, of the English women. She appeared in Kensington Gardens, à l’antique, a muslin dress clinging to her form like the folds of the drapery on a statue; her hair in a plait at the back, and falling in small ringlets round her face, and greasy with huile antique; a large veil thrown over the head, completed her attire, that not unnaturally caused her to be followed and stared at.”

The French Revolution and early Consulate were eminently classical, as regards ladies’ dress; and, as a matter of course, the mode was followed in England, but never to the extent that it was in France. No one can doubt the beauty of this style of dress; but it was one totally unfitted for out-door use, and even for evening dress. It was very slight, and then only fitted for the young and graceful, certainly not for the middle-aged and rotund.

There was a ladies’ magazine, which began in 1806, called La belle Assemblée; and a very good magazine it is. In it, of course, are numerous fashion plates; but I take it that they were then, much as now, intended to be looked at as indications of the fashion, more than the fashion itself. Certainly, in the contemporaneous prints, I have never met with any costume like them, and I much prefer for accuracy of detail, to go to the pictorial satirist, who, if he did somewhat exaggerate, did so on a given basis, an actual costume; and, moreover, threw some life and expression into his groups, which render them better worth looking at, than the meaningless lay-figures, which serve as pegs, on which to hang the clothes of the fashion-monger.

The next three illustrations, which, although designed by an amateur, are etched by Gillray, give us a glimpse of the mysteries of the toilet such as might be sought for in vain elsewhere; they are particularly valuable, as they are in no way exaggerated, and supply details otherwise unprocurable.

After these revelations, no one will be surprised to find that ladies wore false hair. It has been done in all ages: when done, it is no secret, even from casual observers. It was thoroughly understood that it was worn, for was there not always standing witness in the windows of Ross in Bishopsgate Street, and especially in the two bow windows of Cryer, 68, Cornhill – one of which had twenty blocks of gentleman’s, and the other twenty-one of lady’s perukes. One West-end coiffeur thus advertises —Morning Post, March 18, 1800:

“Correct Imitations of Nature.“To Ladies of Rank and Fashion“T. Bowman’s House and Shop being now repaired, is re-opened with every conveniency and accommodation. His new Stock consists of:

“I. Full Dress Head-dresses, made of long hair, judiciously matched, and made to correspond with Nature in every part; the colours genuine; they will dress in any style the best head of hair is capable of; and, in beauty, are far superior. Price 4, 5, 6½, 8, 10, 12, 15, and 20 guineas.

“II. Real Natural Curl Head-dresses. These cannot be described; they must be seen. Price 5 guineas.

“III. Forced Natural Curl Head-dresses are made of such of the Natural Curled Hairs, as have not a sufficient curl; therefore it is assisted by Art: with fine points, of a soft and silky texture, very beautiful. Price 4 guineas.

“IV. Plain Curled Head-dresses are made of Hair, originally straight, but curled by baking, boiled, &c. Price 3 guineas.

“V. The Tresse à la Grecque, when put over the short head-dress, is a complete full dress. Price half-a-guinea, 1, 1½, 2, 3, 4, and 5 guineas.

“In order to account for the apparent high prices of the above, it is necessary to observe, that there are as many qualities of Hair as of Silk, Fur, or Wool (the guinea, and the guinea and a half Wigs, as they are called, can only be made of the refuse, or of Hair procured in this Country); all that Bowman uses is collected at Fairs, from the French Peasants, on the Continent, which (from the present48 convulsed state) is now very dear; as, notwithstanding the artful and false insinuations of interested persons, the importation of last year is not more than one-fifth of former years, and no part of it Men’s Hair.

“☞One thing T. B. intreats Ladies to observe, that he does not expose, or dress his best articles on Heads, Poupées, or Dolls, for Show, the common trick at the Cheap Shops, to hide Defects, as many Ladies know to their cost. His Head-dresses are, until they are sold, the same as a Head of Hair that wants cutting; they are then cut and trimmed to suit the Countenance, or fancy, of the wearer. No article is sold that is not in every respect perfect in fitting; and the most disinterested advice given as to what is fashionable, proper, and becoming. Ladies’ Hair dressed at 3s. 6d., 5s., and 7s. 6d. – No. 102, New Bond Street.”

A few days later on, the same paper (March 21, 1800) relates a fearful story. “Yesterday a bald-pated lady lost her wig on Westminster Bridge; and, to complete her mortification, a near-sighted gentleman, who was passing at the time, addressed the back of her head, in mistake for her face, with a speech of condolence.”

In June of the same year, the same paper takes the ladies to task for their décolletée dresses. “The ladies continue to uncover their necks behind, and well they may; for, since they are covering them before, they cannot be so much afraid of back-biting.”

The Queen and the Princesses set practical lessons in social economy to the ladies of England. The latter were not ashamed to embroider their own dresses for a drawing-room, and the Queen, in order to encourage home manufactures, used Spitalfields silk, or stuffs made in this country; and “stuff balls,” like our “calico” ditto, were not uncommon.

At the end of the first decade of the century costumes became even more bizarre; although, of course, Les Invisibles is an exaggeration. The ordinary out-door dress of ladies of this year is shown in the two following illustrations.

CHAPTER XXXIII

Diversions of people of fashion – Daily life of the King – Children – Education – Girls’ education – Matrimonial advertisements – Gretna Green marriages – Story of a wedding ring – Wife selling – “A woman to let.”

THE ESSAYISTS of Anne’s time did good work, and left precious material for Social History behind them, when they good-humouredly made fun of the little follies of the day; and two satirical prints of Rowlandson’s follow so well in their footprints that I must needs transcribe them. “May 1, 1802. A Man of Fashion’s Journal. ‘Queer dreams, owing to Sir Richard’s claret, always drink too much of it – rose at one – dressed by half-past three – took an hour’s ride – a good horse, my last purchase, remember to sell him again – nothing like variety – dined at six with Sir Richard – said several good things – forgot ‘em all – in high spirits – quizzed a parson – drank three bottles, and loung’d to the theatre – not quite clear about the play – comedy or tragedy – forget which – saw the last act – Kemble toll loll – not quite certain whether it was Kemble or not – Mrs. Siddons monstrous fine – got into a hack – set down in St. James’s Street – dipp’d a little with the boys at hazards – confounded bad luck – lost all my money.’”

“May 1, 1802. A Woman of Fashion’s Journal. ‘Dreamt of the Captain – certainly a fine man – counted my card money – lost considerably – never play again with the Dowager – breakfasted at two, … dined at seven at Lady Rackett’s – the Captain there – more than usually agreeable – went to the Opera – the Captain in the party – house prodigiously crowded – my ci devant husband in the opposite box – rather mal à propos– but no matter —telles choses sont– looked into Lady Squander’s roût– positively a mob – sat down to cards – in great luck – won a cool hundred of my Lord Lackwit, and fifty of the Baron – returned home at five in the morning – indulged in half an hour’s reflection – resolved on reformation, and erased my name from the Picn-ic Society.’”

This style of life was taken more from the Prince of Wales than the King, whose way of living was very simple; and, although this book is intended more to show the daily life of the middle classes, than that of Royalty, still a sketch of the third George’s private daily life cannot be otherwise than interesting. It was this quiet, unassuming daily life of the King, together with his affliction, which won him the hearts of his people.

Morning Post, November 7, 1806: “When the King rises, which is generally about half-past seven o’clock, he proceeds immediately to the Queen’s saloon, where His Majesty is met by one of the Princesses; generally either Augusta, Sophia, or Amelia; for each, in turn, attend their revered Parents. From thence the Sovereign and his Daughter, attended by the Lady in Waiting, proceed to the Chapel, in the Castle, wherein Divine Service is performed by the Dean, or Sub-Dean: the ceremony occupies about an hour. Thus the time passes until nine o’clock, when the King, instead of proceeding to his own apartment, and breakfasting alone, now takes that meal with the Queen, and the five Princesses. The table is always set out in the Queen’s noble breakfasting-room, which has been recently decorated with very excellent modern hangings, and, since the late improvements by Mr. Wyatt, commands a most delightful and extensive prospect of the Little Park. The breakfast does not occupy more than half an hour. The King and Queen sit at the head of the table, according to seniority. Etiquette, in every other respect is strictly adhered to. On entering the room the usual forms are observed, according to rank. After breakfast, the King generally rides out on horseback, attended by his Equerries; three of the Princesses, namely, Augusta, Sophia, and Amelia, are usually of the party. Instead of only walking his horse, His Majesty now proceeds at a good round trot. When the weather is unfavourable, the King retires to his favourite sitting-room, and sends for Generals Fitzroy, or Manners, to play at chess with him. His Majesty, who knows the game well, is highly pleased when he beats the former – that gentleman being an excellent player. The King dines regularly at two o’clock; the Queen and Princesses at four. His Majesty visits, and takes a glass of wine with them, at five. After this period, public business is frequently transacted by the King in his own study, wherein he is attended by his Private Secretary, Colonel Taylor. The evening is, as usual, passed at cards, in the Queen’s Drawing-room, where three tables are set out. To these parties many of the principal nobility, &c., residing in the neighbourhood, are invited. When the Castle clock strikes ten, the visitors retire. The supper is then set out, but that is merely a matter of form, and of which none of the Family partake. These illustrious personages retire at eleven o’clock to rest for the night, and sleep in undisturbed repose until they rise in the morning. The journal of one day is the history of the whole year.”

Children were, in those days, “seen and not heard;” and were very different to the precocious little prigs of the present time. The nursery was their place, and not the unlimited society of, and association with, their elders, as now. When the time for school came, the boys were taught a principally classical education, which was considered, as now, an absolute necessity for a gentleman. Modern languages, with the exception of French and Italian, were not taught. German and the Northern languages were unknown, and Spanish only came to be known during, and after, the Peninsular War. There was no necessity for learning them. As a rule, people did not travel, and, if they did, their courier did all the conversation for them; and there was no foreign literature to speak of which would induce a man to take the trouble to learn languages. The physical sciences were in their infancy, and chemistry, with its wonderful outcome of electricity, was in its veriest babyhood: so that boys were not cumbered with too much learning.

As to young ladies’ education, they had, as they must devoutly have blessed, had they the gift of prescience, no Girton, nor Newnham, nor St. Margaret’s, nor Somerville Halls. Their brains were not addled by exams, or Oxford degrees. Here is their curriculum of study, with its value, in the year 1800. “Terms: – The Young Ladies are boarded, and taught the English and French languages, with grammatical purity and correctness, history and needle-works, for twenty-five guineas per annum, washing included; parlour boarders, forty guineas a year; day boarders, three guineas per quarter; day scholars, a guinea and a half. No entrance money expected, either from boarders or day scholars. Writing, arithmetic, music, dancing, Italian, geography, the use of the globes, and astronomy, taught by professors of eminence and established merit. – Wanted a young lady of a docile disposition, and genteel address, as an apprentice, or half-boarder; she will enjoy many advantages which are not to be met with in the generality of schools. Terms thirty guineas for two years.”

A few years of school, and then, how to get a husband – the same then, as it is now, and ever will be. Matrimonial advertisements were very common, and bear the stamp of authenticity; but the following beats all I have yet seen: “Matrimony – To Noblemen, Ladies, or Gentlemen. Any Nobleman, Lady, or Gentleman, having a female friend who has been unfortunate, whom they would like to see comfortably settled, and treated with delicacy and kindness, and that might, notwithstanding errors, have an opportunity of moving in superior life, by an Union with a Gentleman holding rank in His Majesty’s service, who has been long in possession of a regular and handsome establishment, and whose age, manners, and person, are such (as well as Connections) as, it is to be presumed, will not be objected to, may, by addressing a few lines, post paid, to B. Price, Esqre., to be left at the Bar of the Cambridge Coffee House, Newman Street, form a most desirable Matrimonial union for their friend. The Advertiser is serious, and therefore hopes no one will answer this from idle motives, as much care has been taken to prevent persons from gaining any information, to gratify idle curiosity. The most inviolable honour and secrecy may be relied on, and is expected to be observed throughout the treaty. If the Lady is not naturally vicious, and candour is resorted to, the Gentleman will study, by every means in his power, to promote domestic felicity.”

Marriage at Gretna Green was then in full force, and many were the Couples who went post on that Northern road, and were married by the blacksmith – as we see in Rowlandson’s picture. These Marriages, which were, according to the law of Scotland, perfectly legal and binding, provided the contracting parties avowed themselves to be man and wife before witnesses, were only made illegal by Act of Parliament in 1856, and now it is necessary for one of the parties married, to have resided in Scotland for twenty-one days.