Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

If, however, the times were somewhat gross feeding, yet, early in the century, they also knew the pinch, if not of absolute hunger, yet of that which comes nigh akin to it – scarcity. As we have seen in the History of the decade, bread stuffs were, through bad harvests, very dear; and the strictest attention to economy in their use, even when mixed with inferior substitutes, practised. The unreasoning public laid the whole of the rise in price on the shoulders of the middle-men, or factors; and they were branded with the then opprobrious, but now obsolete, term of “Forestallers and Regraters.” Take one plaintive wail, which appeared in the Morning Post of March 7, 1800: “We are told that one cause of the high price of Corn is, the consequence of the practice of selling by sample, instead of the Corn being fairly brought to market. The middle-man buys the Corn, but desires the farmer to keep it for him, until he wants it; or, in other words, until he finds the price suits his expectations.” This rage against “forestalling” was, of course, very senseless; but it had the advantage of being applied indiscriminately, and to every description of food. Two women at Bristol were imprisoned for “forestalling” a cart load of mackerel; whilst the trial of Waddington for “forestalling” hops is almost a cause célèbre. Now, hops could hardly be construed into food; and, after having carefully read his trial, I can but come to the conclusion that he was a very hardly-used man, and was imprisoned for nothing at all.42 I merely mention his case as a proof of the senseless irritation which the price of food caused upon the unreasoning public.

Food had to be looked for anywhere. The Continent was no field for speculation; a bad harvest had been universal; and, besides, we were at war. Then, for the first time, was India drawn upon for our food supply, and the East India Company – that greatest marvel of all trade – offered every facility towards the export of rice. Their instructions were as follow: “That every ship, which takes on board three quarters of her registered tonnage in rice, shall have liberty to fill up with such goods as have been usually imported by country ships. That ships embarking in this adventure shall be allowed to carry out exports from this country. That they shall be excused the payment of the Company’s duty of 3 per cent., on the rice so imported. That, after the ship shall have been approved by the Company’s surveyors, the risk of the rice which she brings, shall be on account of Government, which will save the owners the expense of insurance. That, in case the price of rice shall, on the ships’ arrival, be under from 32s. to 29s. the hundredweight, the difference between what it may sell for, and the above rates shall be made good to the owners, on the following conditions – That the ship which departs from her port of lading, within one month from the promulgation of these orders, shall be guaranteed 32s. the hundredweight; if in two months, 31s.; if in three months, 30s.; and if in four months, 29s. But, that dependence may be safely placed on the rice being of superior quality, that is, equal, at least, to the best cargo of rice, it shall be purchased by an agent appointed by Government. Coppered ships to be preferred, and, although Convoy43 will, if possible, be obtained for them, they must not be detained for Convoy.”

CHAPTER XXIX

Parliamentary Committee on the high price of provisions – Bounty on imported corn, and on rice from India and America – The “Brown Bread Bill” – Prosecution of bakers for light weight – Punishment of a butcher for having bad meat – Price of beef, mutton, and poultry – Cattle shows – Supply of food from France – Great fall in prices here – Hotels, &c. – A clerical dessert.

PARLIAMENT bestirred itself in the matter of food supply, not only in appointing “a Committee to consider the high price of provisions,” who made their first report on the 24th of November, 1800; but Mr. Dudley Ryder (afterwards Earl of Harrowby) moved, on the 12th of November, in the same year, the following resolutions, which were agreed to: —

“1. That the average price at which foreign corn shall be sold in London, should be ascertained, and published, in the London Gazette.

“2. That there be given on every quarter of wheat, weighing 424 lbs., which shall be imported into the port of London, or into any of the principal ports of each district of Great Britain, before the 1st of October, 1801, a bounty equal to the sum by which the said average price in London, published in the Gazette, in the third week after the importation of such wheat, shall be less than 100s. per quarter.

“3. That there shall be given on every quarter of barley, weighing 352 lbs., which shall be imported into the port of London, or any of the principal ports of each district of Great Britain before the 1st of October, 1801, a bounty equal to the sum by which the said average price in London, published in the Gazette in the third week after the importation of such barley, shall be less than 45s. per quarter.

“4. That there be given on every quarter of rye, weighing 408 lbs., which shall be imported into the port of London, or into any of the principal ports of each district of Great Britain, before the 1st of October, 1801, a bounty equal to the sum by which the said average price in London, published in the Gazette of the third week after the importation of such rye, shall be less than 65s. per quarter.

“5. That there be given on every quarter of oats, weighing 280 lbs., which shall be imported into the port of London, or into any of the principal ports of each district of Great Britain, before the 1st of October, 1801, a bounty equal to the sum by which the average price in London, published in the Gazette in the third week after the importation of such oats, shall be less than 30s. per quarter.

“6. That there be given on every barrel of superfine wheaten flour, of 196 lbs. weight, which shall be imported into such ports before the 1st of October, 1801, and sold by public sale by auction, within two months after importation, a bounty equal to the sum by which the actual price of each barrel of such flour so sold, shall be less than 70s.

“7. That there be given on every barrel of fine wheaten flour, of 196 lbs. weight, which shall be imported into such ports before the 1st of October, 1801, and sold by public sale, by auction, within two months after importation, a bounty equal to the sum by which the actual price of each barrel of such flour so sold shall be less than 68s.

“8. That there be given on every cwt. of rice which shall be imported into such ports in any ship which shall have cleared out from any port in the East Indies before the 1st of September, 1801, and which shall be sold by public sale, a bounty equal to the sum by which the actual price of each cwt. of rice so sold shall be less than 32s.

“9. That there be given on every cwt. of rice, from America, which shall be imported into such ports, before the 1st of October, 1801, and sold by public sale by auction, within two months after importation, a bounty equal to the sum by which the actual price of each cwt. of such rice so sold, shall be less than 35s.”

Thus we see that the paternal government of that day did all they could to find food for the hungry; and it is somewhat curious to note the commencement of a trade for food, with two countries like India and the United States of America. Still more did the Government attempt to alleviate the distress by passing an Act (41 Geo. III. c. 16), forbidding the manufacture of fine bread, and enacting that all bread should contain the whole meal —i. e., all the bran, &c. – and be what we term “brown bread.” Indeed the Act was called, popularly, “The Brown Bread Bill.” It came into force on the 16th of January, 1801, a date which was afterwards extended to the 31st of January, but did not last long; its repeal receiving the Royal Assent on the 26th of February of the same year.

So also the authorities did good service in prosecuting bakers for light weight; and the law punished them heavily. I will only make one quotation —Morning Post, February 5, 1801. “Public Office, Bow Street. Light Bread. Several complaints having been made against a baker in the neighbourhood of Bloomsbury, for selling bread short of weight, he was, yesterday, summoned on two informations; the one for selling a quartern loaf deficient of its proper weight eight ounces, and the other for a quartern loaf wanting four ounces. A warrant was also issued to weigh all the bread in his shop, when 29 quartern loaves were seized, which wanted, together, 58 ounces, of their proper weight; the light bread was brought to the office, and the defendant appeared to answer the charges. The parties were sworn as to the purchase of the first two loaves, which being proved, and the loaves being weighed in the presence of the Magistrates, the defendant was convicted in the full penalty of five shillings per ounce for the twelve ounces they were deficient; and, Mr. Ford observing that as the parties complaining were entitled to one moiety of the penalty, he could not with justice remit any part of it.

“Respecting the other 29 loaves, as it was the report of the officers who executed the warrant, that there were a considerable number more found in his shop that were of full weight, it was the opinion of him, and the other Magistrates then present, that the fine should be mitigated to 2s. per ounce, amounting to £5 16s., which the defendant was, accordingly, obliged to pay, and the 29 loaves, which, of course, were forfeited, Mr. Ford ordered to be distributed to the poor.

“A search warrant was also executed at the shop of a baker near Drury Lane, against whom an information had also been laid for selling light bread; but, it being near three o’clock in the afternoon when the officers went to the shop, very little bread remained, out of which, however, they found eight quarterns, three half quarterns, and four twopenny loaves, short of weight 28 ounces, and on which the baker was adjudged to pay 2s. per ounce, and the bread was disposed of in the same manner as the other.”

As we have seen, the price of bread in London was regulated by the civic authorities, according to the price of flour – and it is gratifying to find that they fearlessly exercised their functions. September 1, 1801: “A number of Bakers were summoned to produce their bills of parcels of flour purchased by them during the last two weeks, according to the returns. Many of them were very irregular which they said was owing to the mealmen not giving in their bills of parcels with the price at the time of delivering the flour. They were ordered to attend on a future day, when the mealmen will be summoned to answer that complaint.”

Nor were the bakers, alone, subject to this vigilance, the butchers were well looked after, and, if evil doers, were punished in a way worthy of the times of the “Liber Albus.” Vide the Morning Post, April 16, 1800: “Yesterday, the carcase of a calf which was condemned by the Lord Mayor, as being unwholesome, was burnt before the butcher’s door, in Whitechapel. His Lordship commended the Inquest of Portsoken Ward very much for their exertions in this business, and hoped it would be an example to others, that when warm weather comes on they may have an eye to stalls covered with meat almost putrified, and very injurious to the health of their fellow citizens.”

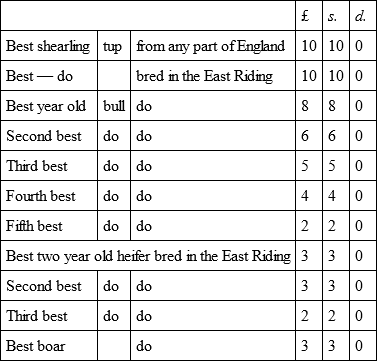

Just at that time meat was extraordinarily high in price – in May, only a few weeks after the above quotation, beef was 1s. 6d. and mutton 1s. 3d. per lb., whilst fowls were 6s. 6d. each, and every other article of food at proportionally high rates. Yet, as was only natural, every means were taken to increase the food supply. Cattle shows were inaugurated, and great interest was taken in them by the neighbouring gentry. As an example we will take one held in September, 1801, where Mr. Tatton Sykes was judge, and there were such well-known county gentlemen present as Mr. Denison, Major Osbaldeston, Major Topham, &c., &c. The prizes were not high; but, then, as now, in agricultural contests, honour went before the money value of the prize.

But, with the treaty of peace with France came comparative plenty. The French were keen enough to, at once, take advantage of the resumption of friendly relations; and, knowing that an era of cheaper food was to be inaugurated, prices fell rapidly here. For instance, no sooner did the news of peace reach Ireland, than the price of pork fell, in some markets from 63s. to 30s. per cwt.; and beef dropped to 33s. 6d. or 30s. 6d. per cwt. Butter, and other farm produce had proportionable reductions. In London, one shopkeeper somewhat whimsically notified the change. At the time of illumination for the peace, he displayed a transparency, on one side of which was a quartern loaf, under which were the words, “I am coming down,” and by its side appeared a pot of porter, which rejoined, “So am I.”

When the pioneer boat, loaded with provisions from France, arrived at Portsmouth, the authorities were at a loss as to what to do with her; so she was detained until an order could be received permitting her to trade and depart within 24 hours. Her cargo was sold out at once, and no wonder, for she sold pigs at 16s. each, turkeys 2s. 6d. each, and fowls 2s. a couple, whilst eggs were going at 1s. 6d. a score.

Whilst on this subject, mention may be made of the kind of provision made for the men’s feeding, otherwise than at home. The Hotel proper, as we know it, was but in its infancy; and, as far as I can gather, there were but some fifteen hotels in London. This does not, of course, include the large coaching inns, which made up beds, because they catered for a fleeting population; nor does it take cognizance of the coffee houses, many of which made up beds, especially for visitors from various counties, where they might possibly meet with friends, or hear the last news about them, and see the county newspaper; whilst all, without exception, and most of the taverns, supplied their customers with dinners, and other food – in fact, they acted as victuallers, and not as the keepers of drinkeries, as now. There were, besides, many of the cheaper class of eating houses, called cook shops, scattered over every part of the town, at which a plentiful dinner might be obtained at, from a shilling, to eighteenpence. In addition, there were very many à la mode beef houses, and soup shops, so that every taste, and purse, was consulted.

Before closing these notes on feeding, early in the century, I must chronicle a “little dinner.” Morning Post, July 26, 1800: “At a village in Cheshire, last year, three clergymen, after dinner, ate fourteen quarts of nuts, and, during their sitting, drank six bottles of port wine, and NO other liquor!”

CHAPTER XXX

Men’s dress – the “Jean de Bry” coat – Short coats fashionable at watering-places – “All Bond Street trembled as he strode” – Rules for the behaviour of a “Bond Street Lounger.”

OF DRESS, either of men, or women, there is little to chronicle during this ten years. The mutations during a similar period, at the close of the previous century, had been so numerous, and radical, as to be sufficient to satisfy any ordinary being; so that, with the exception of the ordinary changes of fashion, which tailors, and milliners will impose upon their victims, there is little to record.

At the commencement of the year 1800, men wore what were then called “Jean de Bry” coats, so named from a French statesman, who was somewhat prominent during the French Revolution – born 1760, died 1834. The accompanying illustration is somewhat exaggerated, not so much as regards the padding on the shoulders, as to the Hessian boots, which latter might, almost, have passed a critical examination, had it not have been that they are furnished with bells, instead of tassels. The coat was padded at the shoulders, to give breadth, and buttoned tight to show the slimness of the waist; yet, as this, under ordinary circumstances, would have hidden the waistcoat – the coat had to be made short-waisted.

Then, the same year, only towards its close, came a craze for short coats, or jackets, resembling the Spencers, but they did not last long, being only fashionable at Brighton, Cheltenham, &c. There seems to have been very little change until 1802, when a modification of the Jean de Bry coat was worn, with the collar increasing very much in height, and boots were discarded in walking.

The portrait of Colonel Duff, afterwards Lord Fyfe, on the next page, is only introduced as an exemplar of costume, and not as a “Bond Street Lounger,” of whom we hear so much, and, as not only may many of my readers like to know something about him, but his character is so amusingly sketched by a contemporary, and the account gives such a vivid picture of the manners of the times, that I transcribe it. It is from the Morning Post of the 6th of February, 1800; and, after premising that the Lounger is comfortably settled at an hotel, the following instructions are given him, as being necessary to establish his character as a young man of fashion. “In short, find fault with every single article, without exception, d – n the waiter at almost regular intervals, and never let him stand one moment still, but ‘keep him eternally moving;’ having it in remembrance that he is only an unfortunate, and wretched subordinate, of course, a stranger to feelings which are an ornament to Human Nature; with this recollection on your part that the more illiberal the abuse he has from you, the greater will be his admiration of your superior abilities, and Gentleman-like qualifications.

Confirm him in the opinion he has so justly imbibed, by swearing the fish is not warm through; the poultry is old, and ‘tough as your Grandmother’; the pastry is made with butter, rank Irish; the cheese, which they call Stilton, is nothing but pale Suffolk; the malt liquor damnable, a mere infusion of malt, tobacco, and cocculus Indicus; the port musty; the sherry sour; and the whole of the dinner and dessert were ‘infernally infamous,’ and, of course, not fit for the entertainment of a Gentleman; conclude the lecture with an oblique hint, that without better accommodations, and more ready attention, you shall be under the necessity of leaving the house for a more comfortable situation. This spirited declaration at starting will answer a variety of purposes, but none so essential as an anticipated objection to the payment of your bill whenever it may be presented. With no small degree of personal ostentation, give the waiter your name ‘because you have ordered your letters there, and, as they will be of importance, beg they may be taken care of, particularly those written in a female hand, of which description, many may be expected.

“Having thus introduced you to, and fixed you, recruit-like, in good quarters, I consider it almost unnecessary to say, however bad you may imagine the wine, I doubt not your own prudence will point out the characteristic necessity for drinking enough, not only to afford you the credit of reeling to bed by the aid of the banister, but the collateral comfort of calling yourself ‘damned queer’ in the morning, owing entirely to the villainous adulteration of the wine, for, when mild and genuine, you can take off three bottles ‘without winking or blinking.’ When rousing from your last somniferous reverie in the morning, ring the bell with no small degree of energy, which will serve to convince the whole family you are awake; upon the entrance of either chamberlain or chambermaid, vociferate half a dozen questions in succession, without waiting for a single reply. As, What morning is it? does it hail, rain, or shine? Is it a frost? Is my breakfast ready? Has anybody enquired for me? Is my groom here? &c., &c. And here it becomes directly in point to observe, that a groom is become so evidently necessary to the ton of the present day (particularly in the neighbourhood of Bond Street) that a great number of Gentlemen keep a groom, who cannot (except upon credit) keep a horse; but then, they are always upon ‘the look out for horses;’ and, till they are obtained, the employment of the groom is the embellishment of both ends of his master, by first dressing his head, and then polishing his boots and shoes.

“The trifling ceremonies of the morning gone through, you will sally forth in search of adventures, taking that great Mart of every virtue, ‘Bond Street,’ in your way. Here it will be impossible for you (between the hours of twelve and four) to remain, even a few minutes, without falling in with various ‘feathers of your wing,’ so true it is, in the language of Rowe, ‘you herd together,’ that you cannot fear being long alone. So soon as three of you are met, adopt a Knight of the Bath’s motto, and become literally ‘Tria juncta in uno,’ or, in other words, link your arms so as to engross the whole breadth of the pavement; the fun of driving fine women, and old dons, into the gutter, is exquisite, and, of course, constitutes a laugh of the most humane sensibility. Never make these excursions without spurs, it will afford not only presumptive proof of your really keeping a horse, but the lucky opportunity of hooking a fine girl by the gown, apron, or petticoat; and, while she is under the distressing mortification of disentangling herself, you and your companions can add to her dilemma by some indelicate innuendo, and, in the moment of extrication, walk off with an exulting exclamation of having ‘cracked the muslin.’ Let it be a fixed rule never to be seen in the Lounge without a stick, or cane; this, dangling in a string, may accidentally get between the feet of any female in passing; if she falls, in consequence, that can be no fault of yours, but the effect of her indiscretion.

“By way of relief to the sameness of the scene, throw yourself loungingly into a chair at Owen’s,44 cut up a pine with the greatest sang froid, amuse yourself with a jelly or two, and, after viewing with a happy indifference whatever may present itself, throw down a guinea (without condescending to ask a question) and walk off; this will not only be politically inculcating an idea of your seeming liberality upon the present; but paving the way to credit upon a future occasion. I had hitherto omitted to mention the necessity for previously providing yourself with a glass (suspended from your button-hole by a string) the want of which will inevitably brand you with vulgarity, if not with indigence; for the true (and, formerly, ‘unsophisticated’) breed of Old John Bull is so very much altered by bad crosses, and a deficiency in constitutional stamina, equally affecting the optic nerves, that there are very few men of fashion can see clear beyond the tip of the nose.

“At the breaking up of the parade, stroll, as it were, accidentally into the Prince of Wales’s Coffee house, in Conduit Street, walk up with the greatest ease, and consummate confidence to every box, in rotation; look at everybody with an inexplicable hauteur, bordering upon contempt; for, although it is most likely you will know little or nothing of them, the great object is, that they should have a perfect knowledge of you. Having repeatedly, and vociferously, called the waiter when he is most engaged, and, at each time asked him various questions equally frivolous and insignificant, seem to skim the surface of the Morning Post (if disengaged), humming the March in Blue Beard,45 to show the versatility of your genius; when, finding you have made yourself sufficiently conspicuous, and an object of general attention (or rather attraction), suddenly leave the room, but not without such an emphatical mode of shutting the door, as may afford to the various companies, and individuals, a most striking proof of your departure.”