Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

But it was not every one who could afford to travel by stage coach, and for them was the stage waggon, or caravan, huge and cumbrous machines, with immensely broad wheels, so as to take a good grip of the road, and make light of the ruts. These machines, and the few canals then in existence, did the inland goods carriage of the whole of England. Slow and laborious was their work, but they poked a few passengers among the goods, and carried them very cheaply. They were a remnant of the previous century, and, in the pages of Smollett, and other writers, we hear a great deal of these waggons.

To give some idea of them, their route, and the time they used to take on their journey, I must make one example suffice, taken haphazard from a quantity. (1802.)

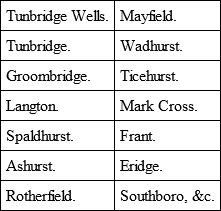

“Tunbridge Wells, and Tunbridge Original Waggon. To the Queen’s Head Inn, Borough.

“By J. Hunt.

“Late Chesseman and Morphew. Under an establishment of more than sixty years. Sets out from the New Inn, Tunbridge Wells, every Monday and Thursday morning, and arrives at the above Inn, every Tuesday and Friday morning, from whence it returns the same days at noon, and arrives at Tunbridge Wells every Wednesday and Saturday afternoon, and from September 1st to December 25th a Waggon sets out from Tunbridge Wells every Wednesday and Saturday morning, and arrives at the above Inn every Monday and Thursday morning, from whence it returns the same days at noon, and arrives at Tunbridge Wells every Tuesday and Friday afternoon, carrying goods and parcels to and from —

“No Money, Plate, Jewels, Writings, Watches, Rings, Lace, Glass, nor any Parcel above Five Pounds Value, will be accounted for, unless properly entered, and paid for as such.

“Waggons or Carts from Tunbridge Wells to Brighton, Eastbourne, &c., occasionally.”

Now Tunbridge is only thirty-six miles from London, and yet it took over twenty-four hours to reach.

Of course, those who had carriages of their own, or hired them, could go “post,” i. e., have fresh horses at certain recognized stations, leaving the tired ones behind them. This was of course travelling luxuriously, and people had to pay for it. In the latter part of the eighteenth century, there had been, well, not a famine, but a great scarcity of corn, and oats naturally rose, so much so that the postmasters had to raise their price, generally to 1s. 2d. per horse per mile, a price which seems to have obtained until the latter part of 1801, when among the advertisements of the Morning Post, September 23rd, I find, “Four Swans, Waltham Cross. Dean Wostenholme begs leave most respectfully to return thanks to the Noblemen and Gentlemen who have done him the honour to use his house, and to inform them that he has lowered the price of Posting to One Shilling per mile,” &c.

And there was, of course, the convenient hackney coach, which was generally the cast-off and used up carriage of some gentleman, whose arms, even, adorned the panels, a practice (the bearing of arms) which still obtains in our cabs. The fares were not extravagant, except in view of the different values of money. Every distance not exceeding one mile 1s., not exceeding one mile and a half, 1s. 6d., not exceeding two miles 2s., and so on. There were many other clauses, as to payment, waiting, radius, &c., but they are uninteresting.

A little book36 says: “The hackney coaches in London were formerly limited to 1,000; but, by an Act of Parliament, the number is increased. Hackney coachmen are, in general, depraved characters, and several of them have been convicted as receivers of stolen goods,” and it goes on to suggest their being licensed.

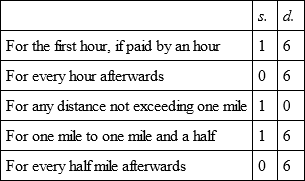

The old sedan chair was not obsolete, but was extensively used to take ladies to evening parties; and, as perhaps we may never again meet with a table of the chairmen’s charges, I had better take it:

RATES OF CHAIRMEN.37

In fact, their fares were almost identical with those of the hackney coachmen, and offending chairmen were subject to the same penalties.

The roads were kept up by means of turnpikes, exemption from payment of which was very rare; royalty, the mails, military officers, &c., on duty, and a few more, were all.

The main roads were good, and well kept; the bye, and occupation roads were bad. But on the main roads there was plenty of traffic to pay for repairs. It was essentially a horsey age – by which I do not mean to infer that our grand and great-grandfathers, copied their grooms either in their dress or manners, as the youth of this generation aspire to do; but the only means of locomotion for any distance was necessarily on horseback, or by means of horse-flesh. Every man could ride, and all wore boots and breeches when out of doors, a style of equine dress unsurpassed to this day.

The carriages were improving in build; no longer being low, and suspended by leather straps, they went to the other extreme, and were perched a-top of high C springs. The Times, January 17, 1803, says: “Many alterations have lately taken place in the building of carriages. The roofs are not so round, nor are the bodies hung so low, as they have been for the last two years. The circular springs have given place to whip springs; the reason is, the first are much more expensive, and are not so light in weight as the others. No boots are now used, but plain coach boxes, with open fore ends. Barouche boxes are now the ton. During the last summer ladies were much oftener seen travelling seated on the box than in the carriage. Hammer-cloths, except on state occasions, are quite out of date, and the dickey box is following their example. To show the difference between the carriages of the present day, and those built ten years ago, it is only necessary to add that in the year 1793 the weight of a fashionable carriage was about 1,900 pounds; a modern one weighs from 1,400 to 1,500.”

CHAPTER XXII

Amateur driving – “The Whip Club” – Their dress – “The Four in Hand Club” – Their dress – Other driving clubs – “Tommy Onslow” – Rotten Row.

CERTAIN of the jeunesse dorée took to driving, probably arising from the fact of riding outside the stage coaches, and being occasionally indulged with “handling the ribbons” and “tooling” the horses for a short distance – of course for a consideration, by means of which “the jarvey”38 made no mean addition to his income, which, by the by, was not a bad one, as every traveller gave him something, and all his refreshment at the various inns at which the coach stopped was furnished free. These young men started a “Whip Club,” and the following is a description of a “meet”:

“The Whip Club met on Monday morning in Park Lane, and proceeded from thence to dine at Harrow-on-the-Hill. There were fifteen barouche landaus with four horses to each; the drivers were all men of known skill in the science of charioteering. Lord Hawke, Mr. Buxton, and the Hon. Lincoln Stanhope were among the leaders.

“The following was the style of the set out: Yellow-bodied carriages, with whip springs and dickey boxes; cattle of a bright bay colour, with plain silver ornaments on the harness, and rosettes to the ears. Costume of the drivers: A light drab colour cloth coat made full, single breast, with three tiers of pockets, the skirts reaching to the ankles; a mother of pearl button of the size of a crown piece. Waistcoat, blue and yellow stripe, each stripe an inch in depth. Small cloths corded with silk plush, made to button over the calf of the leg, with sixteen strings and rosettes to each knee. The boots very short, and finished with very broad straps, which hung over the tops and down to the ankle. A hat three inches and a half deep in the crown only, and the same depth in the brim exactly. Each wore a large bouquet at the breast, thus resembling the coachmen of our nobility, who, on the natal day of our beloved sovereign, appear, in that respect, so peculiarly distinguished. The party moved along the road at a smart trot; the first whip gave some specimens of superiority at the outset by ‘cutting a fly off a leader’s ear.’”39

“ON THE WHIP CLUB“Two varying races are in Briton born,One courts a nation’s praises, one her scorn;Those pant her sons o’er tented fields to guide,Or steer her thunders thro’ the foaming tide;Whilst these, disgraceful born in luckless hour,Burn but to guide with skill a coach and four.To guess their sires each a sure clue affords,These are the coachmen’s sons, and those my Lord’s.Both follow Fame, pursuing different courses;Those, Britain, scourge thy foes – and these thy horses;Give them their due, nor let occasion slip;On those thy laurels lay – on these thy whip!”40According to the Morning Post, April 3, 1809, the title of the “Whip Club” was changed then to the “Four in Hand Club,” and their first meet is announced for the 28th of April. “So fine a cavalcade has not been witnessed in this country, at any period, as these gentlemen will exhibit on that day, in respect to elegantly tasteful new carriages and beautiful horses; the latter will be all high bred cattle, and their estimated value will exceed three hundred guineas each. All superfluous ornaments will be omitted on the harness; gilt, instead of plated furniture.”

The meet took place, as advised, in Cavendish Square, the costume of the drivers being as follows: A blue (single breast) coat, with a long waist, and brass buttons, on which were engraved the words “Four in Hand Club”; waistcoat of Kerseymere, ornamented with alternate stripes of blue and yellow; small clothes of white corduroy, made moderately high, and very long over the knee, buttoning in front over the shin bone. Boots very short, with long tops, only one outside strap to each, and one to the back; the latter were employed to keep the breeches in their proper longitudinal shape. Hat with a conical crown, and the Allen brim (whatever that was); box, or driving coat, of white drab cloth, with fifteen capes, two tiers of pockets, and an inside one for the Belcher handkerchief; cravat of white muslin spotted with black. Bouquets of myrtle, pink, and yellow geraniums were worn. In May of the same year, the club button had already gone out of fashion, and “Lord Hawke sported yesterday, as buttons, Queene Anne’s shillings; Mr. Ashurst displayed crown pieces.”

Fancy driving was not confined to one club; besides the “Four in Hand,” there were “The Barouche Club,” “The Defiance Club,” and “The Tandem Club.”

One of the most showy of these charioteers was a gentleman, who was irreverently termed “Tommy Onslow” (afterwards Lord Cranley), whose portrait is given here. So far did he imitate the regular Jehu that he had his legs swathed in hay-bands. Of him was written, under the picture of which the accompanying is only a portion —

“What can little T. O. do?Why, drive a Phaeton and Two!!Can little T. O. do no more?Yes, drive a Phaeton and Four!!!!”One of his driving feats may be chronicled (Morning Herald, June 26, 1802): “A curious bet was made last week, that Lord Cranley could drive a phaeton and four into a certain specified narrow passage, turn about, and return out of it, without accident to man, horse, or carriage. Whether it was Cranbourn, or Sidney’s Alley, or Russell Court, or the Ride of a Livery Stable, we cannot tell; but, without being able to state the particulars, we understand that the phaetonic feat was performed with dexterity and success, and that his Lordship was completely triumphant.”

In London, of course, the Park was the place for showing off both beautiful horses, and men’s riding, and the accompanying illustration portrays Lord Dillon, an accomplished rider, showing people

The costume here is specially noteworthy, as it shows a very advanced type of dandy.

That this was not the ordinary costume for riding in “the Row,” is shown in the accompanying illustration, where it is far more business-like, and fitted for the purpose.

As we see, from every contemporary print and painting, the horses were of a good serviceable type, as dissimilar as possible from our racer, but closely resembling a well-bred hunter. They had plenty of bottom, which was needful, for they were often called upon to perform what now would be considered as miracles of endurance. Take the following from the Annual Register, March 24, 1802, and bearing in mind the sea passage, without steam, and in a little tub of a boat, and it is marvellous: “Mr. Hunter performed his journey from Paris to London in twenty-two hours, the shortest space of time that journey has ever been made in.”

CHAPTER XXIII

“The Silent Highway” – Watermen – Their fares – Margate hoys – A religious hoy – The bridges over the Thames – The Pool – Water pageants – Necessity for Docks, and their building – Tunnel at Gravesend – Steamboat on the Thames – Canals.

THERE was, however, another highway, well called “the silent.” The river Thames was then really used for traffic, and numerous boats plied for hire from every “stair,” as the steps leading down to the river were called. The watermen were licensed by their Company, and had not yet left off wearing the coat and badge, now alas! obsolete – even the so-called “Doggett’s coat and badge” being now commuted for a money payment. These watermen were not overpaid, and had to work hard for their living. By their code of honour they ought to take a fare in strict rotation, as is done in our present cab ranks – but they were rather a rough lot, and sometimes used to squabble for a fare. Rowlandson gives us such a scene and places it at Wapping Old Stairs.

In 1803 they had, for their better regulation, to wear badges in their hats, and, according to the Times of July the 7th, the Lord Mayor fined several the full penalty of 40s. for disobeying this order, “but promised, if they brought him a certificate of wearing the badge, and other good behaviour, for one month, he would remit the fine.”

Their fares were not exorbitant, and they were generally given a little more – they could be hired, too, by the day, or half day, but this was a matter of agreement, generally from 7s. to 10s. 6d. per diem; and, in case of misbehaviour the number of his boat could be taken, and punishment fell swiftly upon the offender. Taking London Bridge as a centre, the longest journey up the river was to Windsor, and the fare was 14s. for the whole boat, or 2s. each person. Down the river Gravesend was the farthest, the fare for the whole boat being 6s. or 1s. each. These were afterwards increased to 21s. and 15s. respectively. Just to cross the water was cheap enough – 1d. below, and 2d. above the bridge, for each person. It would seem, however, as if some did not altogether abide by the legal fares, for “A Citizen” rushed into print in the Morning Post, September 6, 1810, with the following pitiful tale: “The other night, about nine o’clook, I took a boat (sculls41) at Westminster Bridge to Vauxhall, and offered the waterman, on landing, two shillings (four times his fare) in consideration of having three friends with me; he not only refused to take my money, but, with the greatest insolence, insisted upon having three shillings, to which extortion I was obliged to yield before he would suffer us to leave the shore, and he was aided in his robbery, by his fellows, who came mobbing round us.”

Gravesend was, as a rule, the “Ultima Thule” of the Cockney, although Margate was sometimes reached; but Margate and Ramsgate, to say nothing of Brighton, were considered too aristocratic for tradespeople to frequent, although some did go to Margate. For these long and venturesome voyages, boats called “Hoys” were used – one-masted boats, sometimes with a boom to the mainsail, and sometimes without; rigged very much like a cutter. They are said to have taken their name from being hailed (“Ahoy”) to stop to take in passengers.

People, evidently, thought a voyage on one of these “hoys” a desperate undertaking; for we read in a little tract, of the fearsomeness of the adventure. The gentleman who braves this voyage, is a clergyman, and is bound for Ramsgate. “Many of us who went on board, had left our dearer comforts behind us. ‘Ah!’ said I, ‘so must it be, my soul, when the “Master comes and calleth for thee.” My tender wife! my tender babes! my cordial friends!’… Our vessel, though it set sail with a fair wind, and gently fell down the river towards her destined port, yet once, or twice, was nearly striking against other vessels in the river.” And he winds up with, “About ten o’clock on Friday night we were brought safely into the harbour of Margate… How great are the advantages of navigation! By the skill and care of three men and a boy, a number of persons were in safety conveyed from one part, to another, of the kingdom!”

Sydney Smith in an article (1808) in the Edinburgh Review on “Methodism” quotes a letter in the Evangelical Magazine. “A Religious Hoy sets off every week for Margate. Religious passengers accommodated. To the Editor. Sir, – It afforded me considerable pleasure to see upon the Cover of your Magazine for the present month, an advertisement announcing the establishment of a packet, to sail weekly between London and Margate, during the season; which appears to have been set on foot for the accommodation of religious characters; and in which ‘no profane conversation is to be allowed.’ … Totally unconnected with the concern, and, personally, a stranger to the worthy owner, I take the liberty of recommending this vessel to the notice of my fellow Christians; persuaded that they will think themselves bound to patronize and encourage an undertaking that has the honour of our dear Redeemer for its professed object.”

There were but three bridges over the Thames – London, Blackfriars, and Westminster. London Bridge was doomed to come down. It was out of repair, and shaky; a good many arches blocked up, and those which were open had such a fall, as to be dangerous to shoot. Most of us can remember Blackfriars Bridge, and a good many Old Westminster Bridge, which was described in a London guidebook of 1802, as one of the most beautiful in the world. The same book says, “The banks of the Thames, contiguous to the bridges, and for a considerable extent, are lined with manufactories and warehouses; such as iron founders, dyers, soap and oil-makers, glass-makers, shot-makers, boat builders, &c. &c. To explore these will repay curiosity: in a variety of them, that powerful agent steam performs the work, and steam engines are daily erecting in others. They may be viewed by applying a day or two previous to the resident proprietors, and a small fee will satisfy the man who shows the works.”

The “Pool,” as that portion of the river Thames below London Bridge was called, was a forest of masts. Docks were few, and most of the ships had to anchor in the stream. Loading, and unloading, was performed in a quiet, and leisurely manner, quite foreign to the rush, and hurry of steam. Consequently, the ships lay longer at anchor, and, discharging in mid stream, necessitated a fleet of lighters and barges, which materially added to the crowded state of the river. Add to this the numerous rowing boats employed, either for business, or pleasure, and the river must have presented a far more animated appearance than it does now, with its few mercantile, and pleasure, steamers, and its steam tugs, and launches. Gay, too, were the water pageants, the City Companies barges, for the Lord Mayor’s Show, the Swan Upping, the Conservation of the Thames, and Civic junkettings generally; and then there were the Government barges, both belonging to the Admiralty, and Trinity House, as brave as gold and colour could make them; the latter making its annual pilgrimage to visit the Trinity almshouses at Deptford Strond – all the Brethren in uniform, with magnificent bouquets, and each thoughtfully provided with a huge bag of fancy cakes and biscuits, which they gave away to the rising generation. I can well remember being honoured with a cake, and a kindly pat on the head, from the great Duke of Wellington.

The pressure of the shipping was so great, extending as it did, in unbroken sequence, from London Bridge to Greenwich, that more dock accommodation was needed: the small ones, such as Hermitage and Shadwell Docks, being far too small to relieve the congested state of the river. In 1799 several plans were put forward for new Docks, and some were actually put in progress. The Bill for the West India Docks was passed in 1799. The first stone was laid on the 12th of July, 1800, and the docks were partly opened in the summer of 1802. The first stone of the London Docks was laid on the 26th of June, 1802, and the docks opened on the 30th of January, 1805; and, on the 4th of March of the same year, the foundation of the East India Docks was laid, and they were opened in 1806.

Early in 1801, a shaft was sunk at Gravesend, to tunnel under the Thames, which, although it ultimately came to nothing, showed the nascent power of civil engineering – then just budding – which has in later times borne such fruit as to make it the marvel of the century, in the great works undertaken and accomplished. Even in 1801, there was a steamboat on the Thames (Annual Register, July 1st): “An experiment took place on the river Thames, for the purpose of working a barge, or any other heavy craft, against tide, by means of a steam engine on a very simple construction. The moment the engine was set to work the barge was brought about, answering her helm quickly, and she made way against a strong current, at the rate of two miles and a half an hour.”

Commerce was developing, and the roads, with the heavy and cumbrous waggons, were insufficient for the growing trade. Railways, of course, were not yet, so their precursors, and present rivals, the canals, were made, in order to afford a cheap, and expeditious, means of intercommunication. In July, 1800, the Grand Junction Canal was opened from the Thames at Brentford, to Fenny Stratford in Buckinghamshire. A year afterwards, on the 10th of July, 1801, the Paddington Canal was opened for trade, with a grand aquatic procession, and some idea may be formed of the capital employed on these undertakings, when we find that even in January, 1804, the Grand Junction Canal had a paid-up capital of £1,350,000, and this, too, with land selling at a cheaper proportional rate than now.

CHAPTER XXIV

Condition of the streets of London – Old oil lamps – Improvement in lamps – Gas – Its introduction by Murdoch – Its adoption in London by Winsor – Opposition to it – Lyceum and other places lit with it – Its gradual adoption – The old tinder box – Improvements thereon.

LONDON was considered the best paved city in the world, and most likely it was; but it would hardly commend itself to our fastidious tastes. The main thoroughfares were flagged, and had kerbs; sewers under them, and gratings for the water to run from the gutters into them – but turn aside into a side street, and then you would find a narrow trottoir of “kidney” stones on end, provocative of corns, and ruinous to boots; no sewers to carry off the rain, which swelled the surcharged kennels until it met in one sheet of water across the road. Cellar flaps of wood, closed, or unclosed, and, if closed, often rotten, made pitfalls for all except the excessively wary. Insufficient scavenging and watering, and narrow, and often tortuous, streets, did not improve matters, and when once smallpox, or fever, got hold in these back streets, death held high carnival. Wretchedly lit, too, at night, by poor, miserable, twinkling oil lamps, flickering with every gust, and going out altogether with anything like a wind, always wanting the wicks trimming, and fresh oil, as is shown in the following graphic illustration.

In this, we see a lamp of a most primitive description, and that, too, used at a time when gas was a recognized source of light although not publicly employed. Of course there were improved oil lamps – notably those with the burners of the celebrated M. Argand – and science had already added the reflector, by means of which the amount of light could be increased, or concentrated. In the Times of May 23, 1803, is a description of a new street lamp: “A satisfactory experiment was first made on Friday evening last at the upper end of New Bond Street, to dissipate the great darkness which has too long prevailed in the streets of this metropolis. It consisted in the adaptation of twelve newly invented lamps with reflectors, in place of more than double that number of common ones; and notwithstanding the wetness of the evening, and other unfavourable circumstances, we were both pleased, and surprised to find that part of the street illuminated with at least twice the quantity of light usually seen, and that light uniformly spread, not merely on the footways, but even to the middle of the street, so that the faces of persons walking, the carriages passing, &c., could be distinctly seen; while the lamps and reflectors themselves, presented no disagreeable glare to the eye on looking at them, a fault which has been complained of in lamps furnished with refracting lenses.”