Полная версия

Полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

“At one, the ox and sheep being considered to be sufficiently done, they were taken up. The Bachelors had previously caused boards to be laid from the scene of action to a box, which had been prepared for Her Majesty, and the Royal Family, to survey it from. They graciously accepted the invitation of the Bachelors, to view it close. Their path was railed off and lined by Bachelors, acting as constables, to keep off the crowd. They appeared much gratified by the spectacle, walked round the apparatus and returned to their box. Her Majesty walked with the Duke of York. The Royal party were followed by the Mayor and Corporation. The animals were now placed on dishes to be carved, and several persons, attending for that purpose, immediately set to work. The Bachelors still remained at their posts to keep the crowd off, and a party of them offered the first slice to their illustrious visitors, which was accepted. Shortly after the carving had commenced, and the pudding had began to be distributed, the efforts of the Bachelors to keep off the crowd became useless; some of the Royal Blues, on horseback, assisted in endeavouring to repel them, but without effect. The pudding was now thrown to those who remained at a distance, and now a hundred scrambles were seen in the same instant. The bread was next distributed in a similar way, and, lastly, the meat; a considerable quantity of it was thrown to a butcher, who, elevated above the crowd, catching large pieces in one hand, and holding a knife in the other, cut smaller pieces off, letting them fall into the hands of those beneath who were on the alert to catch them. The pudding,31 meat, and bread, being thus distributed, the crowd were finally regaled with what was denominated a ‘sop in the pan;’ that is, with having the mashed potatoes, gravy, &c., thrown over them.”

Later in the day, Bachelors’ Acre was the scene of renewed festivity, no less than a bull bait. “A fine sturdy animal, kept for the purpose, given to the Bachelors for their amusement, by the same gentleman who gave the ox, was baited; and, in the opinion of the amateurs of bull baiting, furnished fine sport; but, at length, his skin was cut by the rope so much that he bled profusely, and, as it was thought he could not recover, he was led off to be slaughtered.”

At Frogmore, the King gave a fête, and a display of fireworks at night. Everything went off very well, except a portion of the water pageant, which was not a success. “Two cars, or chariots, drawn by seahorses, in one of whom (sic) was a figure of Britannia, in the other a representation of Neptune, appeared majestically moving on the bosom of the lake, followed by four boats filled with persons dressed to represent tritons, &c. These last were to have been composed of choristers, we understand, who were to have sung ‘God save the King,’ on the water, but, unfortunately, the crowd assembled was so immense, that those who were to have sung could not gain entrance. The high treat this could not but have afforded, was, in consequence, lost to the company.”

The Jews celebrated the Jubilee with much enthusiasm, and, in the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, after hearing a sermon preached on a text from Levit. xxv. 13: “In the year of this Jubilee ye shall return every man unto his possession,” we are told “the whole of the 21st Psalm was sung in most expressive style, to the tune of ‘God save the King.’”

In spite of the want of unanimity as to the expediency of a general illumination, there were plenty of transparencies, and even letters of cut-glass. I give descriptions of two of the most important.

“Stubbs’s in Piccadilly, exhibited three transparencies of various dimensions. In the centre was a portrait of His Majesty, in his robes, seated in his coronation chair; the figure was nine feet in height, and the canvas occupied 20 square feet. On the right hand of the King was placed the crown, on a crimson velvet cushion, supported by a table, ornamented with embroidery. Over His Majesty’s head appeared Fame, with her attributes; in her left hand a wreath of laurel leaves; her right pointing to a glory. At the feet of the Sovereign was a group of boys representing Bacchanalians, with cornucopia. Underneath appeared a tablet with the words ‘Anno Regni 50. Oct. 25, 1809.’ On the right and left of the above transparency, were placed representations of the two most celebrated oak-trees in England, and two landscapes – the one of Windsor, and the other of Kew.”

“Messrs. Rundell and Bridge’s, Ludgate Hill. In the centre His Majesty is sitting on his throne, dressed in his coronation robes; on his right, Wisdom, represented by Minerva, with her helmet, ægis, and spear; Justice with her scales and sword; on his left, Fortitude holding a pillar, and Piety with her Bible. Next to Wisdom, Victory is decorating two wreathed columns with oak garlands and gold medallions bearing the names of several successful engagements on land – as Alexandria, Talavera, Vimiera, Assaye, &c. Behind the figure of Fortitude, a female figure is placing garlands and medallions on two other wreathed columns, bearing the names of naval victories – as the First of June, St. Vincent’s, Trafalgar, &c. The base of the throne is guarded by Mars sitting, and Neptune rising, holding his trident, and declaring the triumphs obtained in his dominions; on the base between Mars and Neptune, are boys representing the liberal arts, in basso-relievo. The figures are the size of life.”

The disastrous end of the campaign known as the Walcheren Expedition, brings the year to a somewhat melancholy conclusion, for on Christmas Day, Admiral Otway’s squadron, with all the transports, arrived in the Downs, from Walcheren.

Consols began at 67⅛, and ended at 70, with remarkably little fluctuation. The top price of wheat in January was 90s. 10d., and at the end of December 102s. 10d. It did reach 109s. 6d. in the middle of October – a price we are never likely to see. The quartern loaf, of course, varied in like proportion – January 1s. 2¾d., December 1s. 4¼d., reaching in October 1s. 5d.

CHAPTER XVIII

1810The Scheldt Expedition – The Earl of Chatham and Sir Richard Strachan – The citizens of London and the King – General Fast – Financial disorganization – Issue of stamped dollars – How they were smuggled out of the country – John Gale Jones and John Dean before the House of Commons – Sir Francis Burdett interferes – Publishes libel in Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register– Debate in the House – Sir Francis Burdett committed to the Tower.

ALTHOUGH the Walcheren Expedition was undertaken, and failed, in 1809, it was criticized by the country, both in and out of Parliament, in this year.

It started in all its pride, and glory, on the 28th of July, 1809, a beautiful fleet of thirty-nine sail of the line, thirty-six frigates, besides accompanying gunboats and transports. These were under the command of Sir Richard Strachan, Admiral Otway, and Lord Gardner; whilst the land force of forty thousand men was under the chief command of the Earl of Chatham, who was somewhat notorious for his indolence and inefficiency.

At first, the destination of the fleet was kept a profound secret, but it soon leaked out that Vlissing, or Flushing, in the Island of Walcheren, which lies at the mouth of the Scheldt, was the point aimed at. Middleburgh surrendered to the English on the 2nd of August, and on the 15th after a fearful bombardment, the town of Flushing surrendered. General Monnet, the commander, and over five thousand men were taken prisoners of war.

Nothing was done to take advantage of this success, and, on the 27th of August, when Sir Richard Strachan waited upon the Earl of Chatham to learn the steps he intended to take, he found, to his great disgust, that the latter had come to the conclusion not to advance.

About the middle of September, the Earl, finding that a large army was collecting at Antwerp, thought it would be more prudent to leave with a portion of his army for England, and accordingly did so. He resolved to keep Flushing, and the Island of Walcheren, to guard the mouth of the Scheldt, and keep it open for British commerce; but it was a swampy, pestilential place, and the men sickened, and died of fever, until, at last, the wretched remnant of this fine army was obliged to return, and, on the 23rd of December, 1809, Flushing was evacuated.

Popular indignation was very fierce with regard to the Earl of Chatham, and a scathing epigram was made on him, of which there are scarce two versions alike.

“Lord Chatham, with his sword undrawn,Stood, waiting for Sir Richard Strachan;Sir Richard, longing to be at ‘em,Stood waiting for the Earl of Chatham.”32The Caricaturists, of course, could not leave such a subject alone, and Rowlandson drew two (September 14, 1809). “A design for a Monument to be erected in commemoration of the glorious and never to be forgotten Grand Expedition, so ably planned and executed in the year 1809.” There is nothing particularly witty about this print. Amongst other things it has a shield on which is William, the great Earl of Chatham, obscured by clouds; and the supporters are on one side a “British seaman in the dumps,” and on the other “John Bull, somewhat gloomy, but for what, it is difficult to guess after so glorious an achievement.” The motto is —

“Great Chatham, with one hundred thousand men,To Flushing sailed, and then sailed back again.”And ten days later – on the 24th of September – he published “General Chatham’s marvellous return from his Exhibition of Fireworks.”

The citizens of London were highly indignant at the incapacity displayed by the Earl of Chatham, and in December, they, through the Lord Mayor, memorialized the King, begging him to cause inquiry to be made as to the cause of the failure of the expedition; but George the Third did not brook interference, and he gave them a right royal snubbing. His answer was as follows:

“I thank you for your expressions of duty and attachment to me and to my family.

The recent Expedition to the Scheldt was directed to several objects of great importance to the interest of my Allies, and to the security of my dominions.

I regret that, of these objects, a part, only, has been accomplished. I have not judged it necessary to direct any Military Inquiry into the conduct of my Commanders by Sea or Land, in this conjoint service.

It will be for my Parliament, in their wisdom, to ask for such information, or to take such measures upon this subject as they shall judge most conducive to the public good.”

But the citizens, who bore their share of the war right nobly, would not stand this, and they held a Common Hall on the 9th of January, 1810, and instructed their representatives to move, or support, an Address to His Majesty, praying for an inquiry into the failures of the late expeditions to Spain, Portugal, and Holland. They drew up a similar address, and asserted a right to deliver such address, or petition, to the King upon his throne.

Nothing, however, came of it, and when Parliament was opened, by Commission, on the 23rd of January, 1810, that part of His Majesty’s speech relating to the Walcheren Expedition was extremely brief and unsatisfactory: “These considerations determined His Majesty to employ his forces on an expedition to the Scheldt. Although the principal ends of this expedition had not been attained, His Majesty confidently hopes that advantages, materially affecting the security of His Majesty’s dominions in the further prosecution of the war, will be found to result from the demolition of the docks, and arsenals, at Flushing. This important object His Majesty was enabled to accomplish, in consequence of the reduction of the Island of Walcheren by the valour of his fleets and armies. His Majesty has given directions that such documents and papers should be laid before you, as he trusts will afford satisfactory information upon the subject of this expedition.”

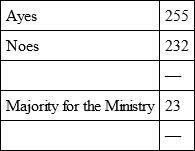

And Parliament had those papers, and fought over them many nights; held, also, a Select Committee on the Scheldt Expedition, and examined many officers thereon; and, finally, on the 30th of March, they divided on what was virtually a vote of censure on the Government, if not carried – a motion declaratory of the approbation of the House in the retention of Walcheren until its evacuation; when the numbers were —

John, Earl of Chatham, had, however, to bow to the storm, and resign his post of Master General of the Ordnance; but his Court favour soon befriended him again. Three years afterwards, he was made full General, and on the death of the Duke of York he was appointed Governor of Gibraltar.

The 28th of February was set apart for the Annual Day of Fasting and Humiliation, and in its routine it resembled all others. The Lords went to Westminster Abbey, the Commons to St. Margaret’s Church, and the Volunteers had Church Parades.

On the 1st of February, Mr. Francis Horner, M.P. for Wendover, moved for a variety of accounts, and returns, respecting the present state of the circulating medium, and the bullion trade. The price of gold was abnormally high, and paper proportionately depreciated. His conjecture to account for this – and it seems a highly probable one – was that the high price of gold might be produced partly by a larger circulation of Bank of England paper than was necessary, and partly by the new circumstances in which the foreign trade of this country was placed, by which a continual demand for bullion was produced, not merely to discharge the balance of trade, as in the ordinary state of things, but for the purpose of carrying on some of the most important branches of our commerce; such as the purchase of naval stores from the Baltic, and grain from countries under the control and dominion of the enemy.

Recourse was had to an issue of Dollars in order to relieve the monetary pressure; and we read in the Morning Post of February 22nd, “A large boat full of dollars is now on its way by the canal, from Birmingham. The dollars have all been re-stamped at Messrs. Bolton and Watts, and will be issued on their arrival at the Bank.” These must not be confounded with the old Spanish dollars which were stamped earlier in the century, and about which there was such an outcry as to the Bank refusing to retake them; but from the same handsome die as those struck in 1804 to guard against forgery – having on the Obverse, the King’s head, with the legend, “Georgius III. Dei Gratia”; and on the Reverse, the Royal Arms, within the garter, crowned, and the legend, “Britanniarum Rex. Fidei Defensor,” and the date.33

But these were snapped up, and smuggled out of the country, as we see by a paragraph in the same paper (March 9th): “Thirty thousand of the re-stamped dollars were seized on board a Dutch Schuyt in the river, a few days since. The public are, perhaps, little aware that the Dutch fishermen, who bring us plaice and eels, will receive nothing in return but gold and silver.” This doubtless was so, but no cargo of fish could have been worth 30,000 dollars.

Gold was scarce, as will be seen by the following note: (April 3rd): “Several ships were last week paid at Plymouth all in new gold coin; and, on Saturday last, the artificers belonging to the Dockyard, were paid their wages in new half-guineas. It was pleasing to see the smiles on the men’s countenances at the sight of these strangers. The Jews and slop merchants are busily employed in purchasing this desirable coin, and substituting provincial and other bank paper in its room.”

That a large, and profitable, trade was done in smuggling the gold coinage out of the country is evident. Morning Post, 28th of July: “Two fresh seizures have lately been made of guineas, which have for some time been so scarce that it is difficult to conceive whence the supply can have been drawn. A deposit of 9,000 guineas, was on Thursday discovered in a snug recess, at the head of the mast of a small vessel in the Thames, which had just discharged a cargo of French wheat; another seizure of 4,500 guineas was made at Deal on the preceding day.”

Morning Post, December 10, 1810: “The tide surveyor at Harwich seized, a few days since, on board a vessel at that port, twenty-two bars of gold, weighing 2,870 ounces. He found the gold concealed between the timbers of the vessel, under about thirty tons of shingle ballast.”

In writing the social history of this year, it would be impossible to keep silence as to the episode of Sir Francis Burdett’s behaviour, and subsequent treatment.

Curiously enough, it arose out of the Scheldt Expedition. On the 19th of February the Right Hon. Charles Yorke, M.P. for Cambridgeshire, rose, and complained of a breach of privilege in a placard printed by a certain John Dean – which was as follows: “Windham and Yorke, British Forum, 33, Bedford Street, Covent Garden, Monday, Feb. 19, 1810. Question: – Which was the greater outrage upon the public feeling, Mr. Yorke’s enforcement of the standing order to exclude strangers from the House of Commons, or Mr. Windham’s recent attack upon the liberty of the press? The great anxiety manifested by the public at this critical period to become acquainted with the proceedings of the House of Commons, and to ascertain who were the authors and promoters of the late calamitous expedition to the Scheldt, together with the violent attacks made by Mr. Windham on the newspaper reporters (whom he described as ‘bankrupts, lottery office keepers, footmen, and decayed tradesmen’) have stirred up the public feeling, and excited universal attention. The present question is therefore brought forward as a comparative inquiry, and may be justly expected to furnish a contested and interesting debate. Printed by J. Dean, 57, Wardour Street.” It was ordered that the said John Dean do attend at the bar of the house the next day.

He did so, and pleaded that he was employed to print the placard by John Gale Jones – and the interview ended with John Dean being committed to the custody of the Serjeant-at-Arms – and John Gale Jones, was ordered to attend the House next day.

When he appeared at the bar, he acknowledged that he was the author of the placard, and regretted that the printer should have been inconvenienced. That he had always considered it the privilege of every Englishman to animadvert on public measures, and the conduct of public men; but that, on looking over the paper again, he found he had erred, and, begging to express his contrition, he threw himself on the mercy of the House.

John Dean, meanwhile, had presented a petition, acknowledging printing the bill, but that it was done by his workmen without his personal attention. He was ordered to be brought to the bar, reprimanded, and discharged – all which came to pass. Gale, however, was committed to Newgate, where he remained until the 21st of June, when Parliament rose, in spite of a motion of Sir Samuel Romilly (April 16th) that he be discharged from his confinement; the House divided – Ayes 112; Noes 160; majority for his further imprisonment, 48.

On a previous occasion (March 12th), Sir Francis Burdett had moved his discharge, but, on a division, fourteen only were for it, and 153 against it. In his speech he denied the legal right of the House to commit any one to prison for such an offence – and he published in Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register of Saturday, March 24, 1810, a long address: “Sir Francis Burdett to his Constituents; denying the power of the House of Commons to imprison the People of England.” It is too long to reproduce, but its tone may be judged of, by the following extract: “At this moment, it is true, we see but one man actually in jail for having displeased those Gentlemen; but the fate of this one man (as is the effect of punishments) will deter others from expressing their opinions of the conduct of those who have had the power, to punish him. And, moreover, it is in the nature of all power, and especially of assumed and undefined power, to increase as it advances in age; and, as Magna Charta and the law of the land have not been sufficient to protect Mr. Jones; as we have seen him sent to jail for having described the conduct of one of the members, as an outrage upon public feeling, what security have we, unless this power of imprisonment be given up, that we shall not see other men sent to jail for stating their opinion respecting Rotten Boroughs, respecting Placemen, and Pensioners, sitting in the House; or, in short, for making any declaration, giving any opinion, stating any fact, betraying any feeling, whether by writing, by word of mouth, or by gesture, which may displease any of the Gentlemen assembled in St. Stephen’s Chapel?” This was supplemented by a most elaborate “Argument,” and on the 27th of March the attention of Parliament was called thereto by Mr. Lethbridge, M.P. for Somerset.

The alleged breach of privilege was read by a clerk, and Sir Francis was called upon to say whatever he could, in answer to the charge preferred against him. He admitted the authorship both of the Address and Argument and would stand the issue of them. Mr. Lethbridge then moved the following resolutions: “1st. Resolved that the Letter signed Francis Burdett, and the further Argument, which was published in the paper called Cobbett’s Weekly Register, on the 24th of this instant, is a libellous and scandalous paper, reflecting upon the just rights and privileges of this House. 2nd. Resolved, That Sir Francis Burdett, who suffered the above articles to be printed with his name, and by his authority, has been guilty of a violation of the privileges of this House.”

The debate was the fiercest of the session. It was adjourned to the 28th, and the 5th of April, when Mr. Lethbridge’s resolutions were agreed to without a division, and Sir Robert Salusbury, M.P. for Brecon, moved that Sir Francis Burdett be committed to the Tower. An amendment was proposed that he be reprimanded in his place; but, on being put, it was lost by 190 to 152 – 38, and at seven o’clock in the morning of the 6th of April, Sir Francis’s doom was decreed.

CHAPTER XIX

Warrant served on Sir Francis Burdett – He agrees to go to prison – Subsequently he declares the warrant illegal – His arrest – His journey to the Tower – The mob – His incarceration – The mob attack the military – Collision – Killed and wounded – Sir Francis’s letter to the Speaker – His release – Conduct of the mob.

UP TO this time the proceedings had been grave and dignified, but Sir Francis imported a ludicrous element into his capture.

Never was any arrest attempted in so gentlemanlike, and obliging a manner.34 At half-past seven o’clock in the morning, as soon as the division in the House of Commons was known, Mr. Jones Burdett, accompanied by Mr. O’Connor, who had remained all night at the House of Commons, set off in a post chaise to Wimbledon, and informed Sir Francis Burdett of the result. Sir Francis immediately mounted his horse, and rode to town. He found a letter on his table from Mr. Colman, the Serjeant-at-Arms, acquainting him that he had received a warrant, signed by the Speaker, to arrest and convey him to the Tower, and he begged to know when he might wait on him; that it was his wish to show him the utmost respect, and, therefore, if he preferred to take his horse, and ride to the Tower, he would meet him there.

To this very courteous and considerate letter, Sir Francis replied that he should be happy to receive him at noon next day. However, before this letter could reach the Serjeant-at-Arms, he called on Sir Francis, and verbally informed him that he had a warrant against him. Sir Francis told him he should be ready for him at twelve next day, and Mr. Colman bowed, and retired. Indeed it was so evidently the intention of the baronet to go to his place of durance quietly, that, in the evening, he sent a friend to the Tower to see if preparations had been made to receive him, and it was found that every consideration for his comfort had been taken.

But the urbane Serjeant-at-Arms, when he made his report to the Speaker, was mightily scolded by him for not executing his warrant, and at 8 p.m. he called, with a messenger, on Sir Francis, and told him that he had received a severe reprimand from the Speaker for not executing his warrant in the morning, and remaining with his prisoner.