Полная версия

Полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

For this great Pope, however, there was no greater teacher of any of the serious philosophical, ethical and theological problems than this Saint of the Thirteenth Century. His position in the matter would only seem exaggerated to those who do not appreciate Pope Leo's marvelous practical intelligence, and Saint Thomas's exhaustive treatment of most of the questions that have always been uppermost in the minds of men. While, with characteristic humility, he considered himself scarcely more than a commentator on Aristotle, his natural genius was eminently original and he added much more of his own than what he took from his master. There can be no doubt that his was one of the most gifted minds in all humanity's history and that for profundity of intelligence he deserves to be classed with Plato and Aristotle, as his great disciple Dante is placed between Homer and Shakespeare. Those who know St. Thomas the best, and have spent their lives in the study of him, not only cordially welcomed but ardently applauded Pope Leo's commendation of him, and considered that lofty as was his praise there was not a word they would have changed even in such a laudatory passage as the following:

"While, therefore, we hold that every word of wisdom, every useful thing by whomsoever discovered or planned, ought to be received with a willing and grateful mind. We exhort you, Venerable Brethren, in all earnestness to restore the golden wisdom of St. Thomas, and to spread it far and wide for the defense and beauty of the Catholic faith, for the good of society, and for the advantage of all the sciences. The wisdom of St. Thomas, We say—for if anything is taken up with too great subtlety by the scholastic doctors, or too carelessly stated—if there is anything that ill agrees with the discoveries of a later age, or, in a word, improbable in whatever way, it does not enter Our mind, to propose that for imitation to Our age. Let carefully selected teachers endeavor to implant the doctrines of Thomas Aquinas in the minds of students, and set forth clearly his solidity and excellence over others. Let the academies already founded or to be founded by you illustrate and defend this doctrine, and use it for refutation of prevailing errors. But, lest the false for the true or the corrupt for the pure be drunk in, be watchful that the doctrine of Thomas be drawn from his own fountains, or at least from those rivulets which derived from the very fount, have thus far flowed, according to the established agreement of learned men, pure and clear; be careful to guard the minds of youth from those which are said to flow thence, but in reality are gathered from strange and unwholesome streams."

Tributes quite as laudatory are not lacking from modern secular writers and while there have been many derogatory remarks, these have always come from men who either knew Aquinas only at second hand, or who confess that they had been unable to read him understandingly. The praise all comes from men who have spent years in the study of his writings.

A recent writer in the Dublin Review (January, 1906) sums up his appreciation of one of St. Thomas's works, his masterly book in philosophy, as follows:

"The Summa contra Gentiles is an historical monument of the first importance for the history of philosophy. In the variety of its contents, it is a perfect encyclopedia of the learning of the day. By it we can fix the high-water mark of Thirteenth Century thought, for it contains the lectures of a doctor second to none in the great school of thought then flourishing—the University of Paris. It is by the study of such books that one enters into the mental life of the period at which they were written; not by the hasty perusal of histories of philosophy. No student of the Contra Gentiles is likely to acquiesce in the statement that the Middle Ages were a time when mankind seemed to have lost the power of thinking for themselves. Medieval people thought for themselves, thoughts curiously different from ours and profitable to study."

Here is a similar high tribute for Aquinas's great work on Theology from his modern biographer, Father Vaughan:

"The 'Summa Theologica' is a mighty synthesis, thrown into technical and scientific form, of the Catholic traditions of East and West, of the infallible dicta of the Sacred Page, and of the most enlightened conclusions of human reason, gathered from the soaring intuitions of the Academy, and the rigid severity of the Lyceum.

"Its author was a man endowed with the characteristic notes of the three great Fathers of Greek Philosophy: he possessed the intellectual honesty and precision of Socrates, the analytical keenness of Aristotle, and that yearning after wisdom and light which was the distinguishing mark of 'Plato the divine,' and which has ever been one of the essential conditions of the highest intuitions of religion."

As a matter of fact it was the very greatness of Thomas Aquinas, and the great group of contemporaries who were so close to him, that produced an unfortunate effect on subsequent thinking and teaching in Europe. These men were so surpassing in their grasp of the whole round of human thought, that their works came to be worshiped more or less as fetishes, and men did not think for themselves but appealed to them as authorities. It is a great but an unfortunate tribute to the scholastics of the Thirteenth Century that subsequent generations for many hundred years not only did not think that they could improve on them, but even hesitated to entertain the notion that they could equal them. Turner in his History of Philosophy has pointed out this fact clearly and has attributed to it, to a great extent, the decadence of scholastic philosophy.

"The causes of the decay of scholastic philosophy were both internal and external. The internal causes are to be found in the condition of Scholastic philosophy at the beginning of the Fourteenth Century. The great work of Christian syncretism had been completed by the masters of the preceding period; revelation and science had been harmonized; contribution had been levied on the pagan philosophies of Greece and Arabia, and whatever truth these philosophies had possessed had been utilized to form the basis of a rational exposition of Christian revelation. The efforts of Roger Bacon and of Alfred the Great to reform scientific method had failed; the sciences were not cultivated. There was, therefore, no source of development, and nothing was left for the later Scholastics except to dispute as to the meaning of principles, to comment on the text of this master or of that, and to subtilize to such an extent that Scholasticism soon became a synonym for captious quibbling. The great Thomistic principle that in philosophy the argument from authority is the weakest of all arguments was forgotten; Aristotle, St. Thomas, or Scotus became the criterion of truth, and as Solomon, whose youthful wisdom had astonished the world, profaned his old age by the worship of idols, the philosophy of the schools, in the days of its decadence, turned from the service of truth to prostrate itself before the shrine of a master. Dialectic, which in the Thirteenth Century had been regarded as the instrument of knowledge, now became an object of study for the sake of display; and to this fault of method was added a fault of style—an uncouthness and barbarity of terminology which bewilder the modern reader."

The appreciation of St. Thomas in his own time is the greatest tribute to the critical faculty of the century that could be made. "Genius is praised but starves," in the words of the old Roman poet. Certainly most of the geniuses of the world have met with anything but their proper meed of appreciation in their own time. This is not true, however, during our Thirteenth Century. We have already shown how the artists, and especially Giotto, (at the end of the Thirteenth Century Giotto was only twenty-four years old) were appreciated, and how much attention Dante began to attract from his contemporaries, and we may add that all the great scholars of the period had a following that insured the wide publication of their works, at a time when this had to be accomplished by slow and patient hand-labor. The appreciation for Thomas, indeed, came near proving inimical to his completion of his important works in philosophy and theology. Many places in Europe wanted to have the opportunity to hear him. We have only reintroduced the practise of exchanging university professors in very recent years. This was quite a common practise in the Thirteenth Century, however, and so St. Thomas, after having been professor at Paris and later at Rome, taught for a while at Naples and then at a number of the Italian universities.

Everywhere he went he was noted for the kindliness of his disposition and for his power to make friends. Looked upon as the greatest thinker of his time it would be easy to expect that there should be some signs of consciousness of this, and as a consequence some of that unpleasant self-assertion which so often makes great intellectual geniuses unpopular. Thomas, however, never seems to have had any over-appreciation of his own talents, but, realizing how little he knew compared to the whole round of knowledge, and how superficial his thinking was compared to the depth of the mysteries he was trying, not to solve but to treat satisfactorily, it must be admitted that there was no question of conceit having a place in his life. This must account for the universal friendship of all who came in contact with him. The popes insisted on having him as a professor at the Roman university in which they were so much interested, and which they wished to make one of the greatest universities of the time. Here Thomas was brought in contact with ecclesiastics from all over the world and helped to form the mind of the time. Those who think the popes of the Middle Ages opposed to education should study the records of this Roman university.

Thomas became the great friend of successive popes, some of whom had been brought in contact with him during his years of studying and teaching at Rome and Paris. This gave him many privileges and abundant encouragement, but finally came near ruining his career as a philosophic writer and teacher, since his papal friends wished to raise him to high ecclesiastical dignities. Urban IV. seems first to have thought of this but his successor Clement IV., one of the noblest churchmen of the period, who had himself wished to decline the papacy, actually made out the Bull, creating Thomas Archbishop of Naples. When this document was in due course presented to Aquinas, far from giving him any pleasure it proved a source of grief and pain. He saw the chance to do his life-work slipping from him. This was so evident to his friend the Pope that he withdrew the Bull and St. Thomas was left in peace during the rest of his career, and allowed to prosecute that one great object to which he had dedicated his mighty intellect. This was the summing up of all human knowledge in a work that would show the relation of the Creator to the creature, and apply the great principles of Greek philosophy to the sublime truths of Christianity. Had Thomas consented to accept the Archbishopric of Naples in all human probability, as Thomas's great English biographer remarks, the Summa Theologica would never have been written. It seems not unlikely that the dignity was pressed upon him by the Pope partly at the solicitation of powerful members of his family, who hoped in this to have some compensation for their relative's having abandoned his opportunities for military and worldly glory. It is fortunate that their efforts failed, and it is only one of the many examples in history of the short-sightedness there may be in considerations that seem founded on the highest human prudence.

Thomas was left free then to go on with his great work, and during the next five years he applied every spare moment to the completion of his Summa. More students have pronounced this the greatest work ever written than is true for any other text-book that has ever been used in schools. That it should be the basis of modern theological teaching after seven centuries is of itself quite sufficient to proclaim its merit. The men who are most enthusiastic about it are those who have used it the longest and who know it the best.

St. Thomas's English biographer, the Very Rev. Roger Bede Vaughan, who is a worthy member of that distinguished Vaughan family who have given so many zealous ecclesiastics to the English Church and so many scholars to support the cause of Christianity, can scarcely say enough of this great work, nor of its place in the realm of theology. When it is recalled that Father Vaughan was not a member of St. Thomas's own order, the Dominicans, but of the Benedictines, it will be seen that it was not because of any esprit de corps, but out of the depths of his great admiration for the saint, that his words of praise were written:

"It has been shown abundantly that no writer before the Angelical's day could have created a synthesis of all knowledge. The greatest of the classic Fathers have been treated of, and the reasons of their inability are evident. As for the scholastics who more immediately preceded the Angelical, their minds were not ripe for so great and complete a work: the fullness of time had not yet come. Very possibly had not Albert the Great and Alexander (of Hales) preceded him, St. Thomas would not have been prepared to write his master-work; just as, most probably, Newton would never have discovered the law of gravitation had it not been for the previous labors of Galileo and of Kepler. But just as the English astronomer stands solitary in his greatness, though surrounded and succeeded by men of extraordinary eminence, so also the Angelical stands by himself alone, although Albertus Magnus was a genius, Alexander was a theological king, and Bonaventure a seraphic doctor. Just as the Principia is a work unique, unreachable, so, too, is the 'Summa Theologica' of the great Angelical. Just as Dante stands alone among the poets, so stands St. Thomas in the schools."

Probably the most marvelous thing about the life of St. Thomas is his capacity for work. His written books fill up some twenty folios in their most complete edition. This of itself would seem to be enough to occupy a lifetime without anything more. His written works, however, represent apparently only the products of his hours at leisure. He was only a little more than fifty when he died and he had been a university professor at Cologne, at Bologna, at Paris, at Rome, and at Naples. In spite of the amount of work that he was thus asked to do, his order, the Dominican, constantly called on him to busy himself with certain of its internal affairs. On one occasion at least he visited England in order to attend a Dominican Chapter at Oxford, and the better part of several years at Paris was occupied with his labors to secure for his brethren a proper place in the university, so that they might act as teachers and yet have suitable opportunities for the education and the discipline of the members of the Order.

Verily it would seem as though his days must have been at least twice as long as those of the ordinary scholar and student to accomplish so much; yet he is only a type of the monks of the Middle Ages, of whom so many people seem to think that their principal traits were to be fat and lazy. Thomas was fat, as we know from the picture of him which shows him before a desk from which a special segment has been removed to accommodate more conveniently a rather abnormal abdominal development, but as to laziness, surely the last thing that would occur to anyone who knows anything about him, would be to accuse him of it. Clearly those who accept the ancient notion of monkish laziness will never understand the Middle Ages. The great educational progress of the Thirteenth Century was due almost entirely to monks.

There is another extremely interesting side to the intellectual character of Thomas Aquinas which is usually not realized by the ordinary student of philosophy and theology, and still less perhaps by those who are interested in him from an educational standpoint. This is his poetical faculty. For Thomas as for many of the great intellectual geniuses of the modern time, the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist was one of the most wondrously satisfying devotional mysteries of Christianity and the subject of special devotion. In our own time the great Cardinal Newman manifested this same attitude of mind. Thomas because of his well-known devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, was asked by the Pope to write the office for the then recently established feast of Corpus Christi. There are always certain hymns incorporated in the offices of the different Feast days. It might ordinarily have been expected that a scholar like Aquinas would write the prose portions of the office, leaving the hymns for some other hand, or selecting hymns from some older sacred poetry. Thomas, however, wrote both hymns and prose, and, surprising as it may be, his hymns are some of the most beautiful that have ever been composed and remain the admiration of posterity.

It must not be forgotten in this regard that Thomas's career occurred during the period when Latin hymn writing was at its apogee. The Dies Irae and the Stabat Mater were both written during the Thirteenth Century, and the most precious Latin hymns of all times were composed during the century and a half from 1150 to 1300. Aquinas's hymns do not fail to challenge comparison even with the greatest of these. While he had an eminently devotional subject, it must not be forgotten that certain supremely difficult theological problems were involved in the expression of devotion to the Blessed Sacrament. In spite of the difficulties, Thomas succeeded in making not only good theology but great poetry. A portion of one of his hymns, the Tantum Ergo, has been perhaps more used in church services than any other, with the possible exception of the Dies Irae. Another one of his beautiful hymns that especially deserves to be admired, is less well known and so I have ventured to quote three selected stanzas of it, as an illustration of Thomas's command over rhyme and rhythm in the Latin tongue.24

Adoro te devote, latens Deitas, Quae sub his figuris vere latitas. Tibi se cor meum totum subjicit, Quia te contemplans totum deficit. Visus, tactus, gustus, in te fallitur, Sed auditu solo tute creditur: Credo quidquid dixit Dei filius Nihil veritatis verbo verius.And the less musical but wonderfully significative fourth, stanza—

Plagas sicut Thomas non intueor, Deum tamen meum te confiteor, Fac me tibi semper magis credere, In te spem habere, te diligere.Only the ardent study of many years will give anything like an adequate idea of the great schoolman's universal genius. I am content if I have conveyed a few hints that will help to a beginning of an acquaintance with one of the half dozen supreme minds of our race.

Hidden God, devoutly I adore thee, Truly present underneath these veils: All my heart subdues itself before thee. Since it all before thee faints and fails. Not to sight, or taste, or touch be credit. Hearing only do we trust secure; I believe, for God the Son hath said it— Word of truth that ever shall endure. … Though I look not on thy wounds with Thomas, Thee, my Lord, and thee, my God, I call: Make me more and more believe thy promise, Hope in thee, and love thee over all.]

XVIII

ST. LOUIS THE MONARCH

If large numbers of men are to be ruled by one of their number, as seems more or less inevitable in the ordinary course of things, then, without doubt, the best model of what such a monarch's life should be, is to be found in that of Louis IX., who for nearly half a century was the ruler of France during our period. Of all the rulers of men of whom we have record in history he probably took his duties most seriously, with most regard for others, and least for himself and for his family. There is not a single relation of life in which he is not distinguished and in which his career is not worth studying, as an example of what can be done by a simple, earnest, self-forgetful man, to make life better and happier for all those who come in contact with him.

His relations with his mother are those of an affectionate son in whom indeed, from his easy compliance with her wishes in his younger years one might suspect some weakness, but whose strength of character is displayed at every turn once he himself assumed the reins of government. After many years of ruling however, when his departure on the Crusade compelled him to be absent from the kingdom it was to her he turned again to act as his representative and the wisdom of the choice no one can question. As a husband Louis' life was a model, and though he could not accomplish the impossible, and was not able to keep the relations of his mother and his wife as cordial as he would have liked them to be, judging from human experience generally it is hard to think this constitutes any serious blot on his fair name. As a father, few men have ever thought less of material advantages for their children, or more of the necessity for having them realize that happiness in life does not consist in the possession of many things, but rather in the accomplishment of duty and in the recognition of the fact that the giving of happiness to others constitutes the best source of felicity for one's self. His letters and instructions to his children, as preserved for us by Joinville and other contemporaries, give us perhaps the most taking picture of the man that we have, and round out a personality, which, while it has in the telling French phrase "the defects of its virtues," is surely one of the most beautiful characters that has ever been seen upon earth, in a man who took an active and extremely important part in the great events of the world of his time.

The salient points of his character are his devotion to the three great needs of humanity as they present themselves in his time. He made it the aim of his life that men should have justice, and education, and when for any misfortune they needed it,—charity; and every portion of his career is taken up with successful achievement in these great departments of social action. It is well known that when he became conscious that the judges sometimes abused their power and gave sentences for partial reasons, the monarch himself took up the onerous duty of hearing appeals and succeeded in making the judges of his kingdom realize, that only the strictest justice would save them from the king's displeasure, and condign punishment. For an unjust judge there was short shrift. The old tree at Versailles, under which he used to hear the causes of the poor who appealed to him, stood for many centuries as a reminder of Louis' precious effort to make the dispensing of justice equal to all men. When the duty of hearing appeals took up too much of his time it was transferred to worthy shoulders, and so the important phase of jurisprudence in France relating to appeals, came to be thoroughly established as a part of the organic law of the kingdom.

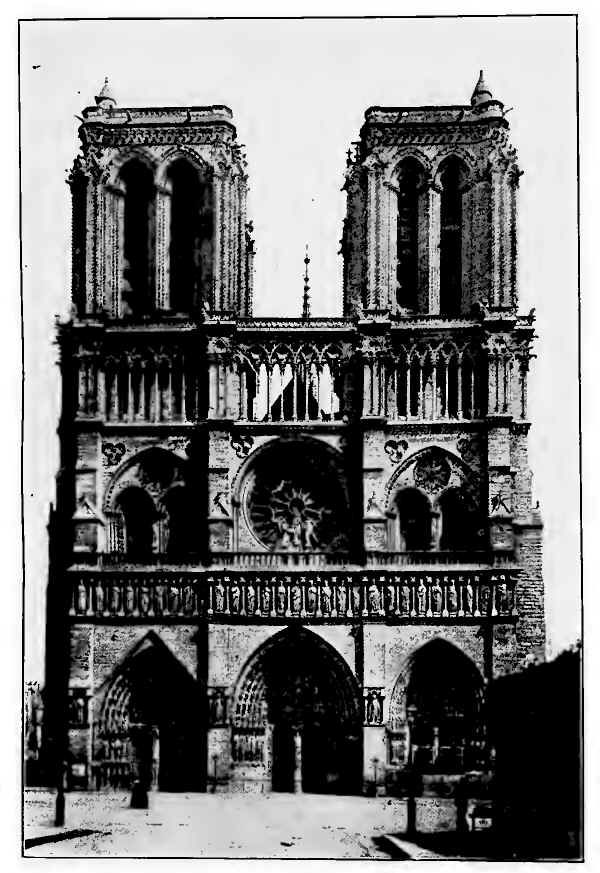

NOTRE DAME (PARIS)

As regards education, too much can not be said of Louis' influence. It is to him more than to anybody else that the University of Paris owes the success it achieved as a great institution of learning at the end of the Thirteenth Century. Had the monarch been opposed to the spread of education with any idea that it might possibly undermine his authority, had he even been indifferent to it, Paris would not have come to be the educational center of the world. As it was, Louis not only encouraged it in every way, but also acted as the patron of great subsidiary institutions which were to add to its prestige and enhance its facilities. Among the most noteworthy is the Sorbonne. La Sainte Chapelle deserves to be mentioned, however, and the library attached to it, which owed its foundation and development to Louis, were important factors in attracting students to Paris and in furnishing them interestingly suggestive material for thought and the development of taste during their residence there. His patronage of Vincent of Beauvais, the encyclopedist, was but a further manifestation of his interest in everything educational. His benefactions to the Hotel Dieu must be considered rather under the head of charity, and yet they also serve to represent his encouragement of medical education and of the proper care for the poor in educated hands.