Полная версия

Полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

With regard to what was accomplished in philosophic and theologic prose, examples will be found in the chapter on St. Thomas Aquinas, which prove beyond all doubt the utter simplicity, the directness, and the power of the prose of the Thirteenth Century. In the medical works of the time there was less directness, but always a simplicity that made them commendable. In general, university writers were influenced by the scholastic methods and we find it reflected constantly in their works. In the minds of many people this would be enough at once to condemn it. It will usually be found, however, as we have noted before, that those who are readiest to condemn scholastic writing know nothing about it, or so little that their opinion is not worth considering. Usually they have whatever knowledge they think they possess, at second hand. Sometimes all that they have read of scholastic philosophy are some particularly obscure passages on abstruse subjects, selected by some prejudiced historian, in order to show how impossible was the philosophic writing of these centuries of the later Middle Ages.

There are other opinions, however, that are of quite different significance and value. We shall quote but one of them, written by Professor Saintsbury of the University of Edinburgh, who in his volume on the Flourishing of Romance and the Rise of Allegory (the Twelfth and Thirteenth centuries) of his Periods of European Literature, has shown how sympathetically the prose writing of the Thirteenth Century may appeal even to a scholarly modern, whose main interests have been all his life in literature. Far from thinking that prose was spoiled by scholasticism. Prof. Saintsbury considers that scholasticism was the fortunate training school in which all the possibilities of modern prose were brought out and naturally introduced into the budding languages of the time. He says:

"However this may be" (whether the science of the Nineteenth Century after an equal interval will be of any more positive value, whether it will not have even less comparative interest than that which appertains to the scholasticism of the Thirteenth Century) "the claim modest, and even meager as it may seem to some, which has been here once more put forward for this scholasticism—the claim of a far-reaching educative influence in mere language, in mere system of arrangement and expression, will remain valid. If at the outset of the career of modern languages, men had thought with the looseness of modern thought, had indulged in the haphazard slovenliness of modern logic, had popularized theology and vulgarized rhetoric, as we have seen both popularized and vulgarized since, we should indeed have been in evil case. It used to be thought clever to moralize and to felicitate mankind over the rejection of the stays, the fetters, the prison in which its thought was medievally kept. The justice or the injustice, the taste or the vulgarity of these moralizings, of these felicitations, may not concern us here. But in expression, as distinguished from thought, the value of the discipline to which these youthful languages was subjected is not likely now to be denied by any scholar who has paid attention to the subject. It would have been perhaps a pity if thought had not gone through other phases; it would certainly have been a pity if the tongues had been subjected to the fullest influence of Latin constraint. But that the more lawless of them benefited by that constraint there can be no doubt whatever. The influence of form which the best Latin hymns of the Middle Ages exercised in poetry, the influence in vocabulary and in logical arrangement which scholasticism exercised in prose are beyond dispute: and even those who will not pardon literature, whatever its historic and educative importance be, for being something less than masterly in itself, will find it difficult to maintain the exclusion of the Cur Deus Homo, and impossible to refuse admission to the Dies Irae."

Besides this philosophic and scientific prose, there were two forms of writing of which this century presents a copious number of examples. These are the chronicles and biographies of the time and the stories of travelers and explorers. These latter we have treated in a separate chapter. The chronicles of the time deserve to be studied with patient attention by anyone who wishes to know the prose writers of the century and the character of the men of that time and their outlook on life. It is usually considered that chroniclers are rather tiresome old fogies who talk much and say very little, who accept all sorts of legends on insufficient authority and who like to fill up their pages with wonderful things regardless of their truth. In this regard it must not be forgotten that in times almost within the memory of men still alive, Herodotus now looked upon deservedly as the Father of History and one of the great historical writers of all time, was considered to have a place among these chroniclers, and his works were ranked scarcely higher, except for the purity of their Greek style.

The first of the great chroniclers in a modern tongue was the famous Geoffrey de Villehardouin, who was not only a writer of, but an actor in the scenes which he describes. He was enrolled among the elite of French Chivalry, in that Crusade at the beginning of the Thirteenth Century, which resulted in the foundation of the Greco-Latin Empire. His book entitled "The Conquest of Constantinople," includes the story of the expedition during the years from 1198 to 1207. Modern war correspondents have seldom succeeded in giving a more vivid picture of the events of which they were witnesses than this first French chronicler of the Thirteenth Century. It is evident that the work was composed with the idea that it should be recited, as had been the old poetic Chansons de Geste, in the castles of the nobles and before assemblages of the people, perhaps on fair days and other times when they were gathered together. The consequence is that it is written in a lively straightforward style with direct appeals to its auditors.

It contains not a few passages of highly poetic description which show that the chronicler was himself a literary man of no mean order and probably well versed in the effusions of the old poets of this country. His description of the fleet of the Crusaders as it was about to set sail for the East and then his description of its arrival before the imposing walls of the Imperial City, are the best examples of this, and have not been surpassed even by modern writers on similar topics.

Though the French writer was beyond all doubt not familiar with the Grecian writers and knew nothing of Xenophon, there is a constant reminder of the Greek historian in his work. Xenophon's simple directness, his thorough-going sincerity, the impression he produces of absolute good faith and confidence in the completeness of the picture, so that one feels that one has been present almost at many of the scenes described, are all to be encountered in his medieval successor. Villehardouin went far ahead of his predecessors, the chroniclers of foregoing centuries, in his careful devotion to truth. A French writer has declared that to Villehardouin must be ascribed the foundation of historical probity. None of his facts, stated as such, has ever been impugned, and though his long speeches must necessarily have been his own composition, there seems no doubt that they contain the ideas which had been expressed on various occasions, and besides were composed with due reference to the character of the speaker and convey something of his special style of expression.

Prof. Saintsbury in his article in the Encyclopedia Britannica on Villehardouin, sums up very strikingly the place that this first great vernacular historian's book must occupy.

He says: "It is not impertinent, and at the same time an excuse for what has been already said, to repeat that Villehardouin's book, brief as it is, is in reality one of the capital books of literature, not merely for its merit, but because it is the most authentic and the most striking embodiment in the contemporary literature of the sentiments which determined the action of a great and important period of history. There are but very few books which hold this position, and Villehardouin's is one of them. If every other contemporary record of the crusades perished, we should still be able by aid of this to understand and realize what the mental attitude of crusaders, of Teutonic Knights, and the rest was, and without this we should lack the earliest, the most undoubtedly genuine, and the most characteristic of all such records. The very inconsistency with which Villehardouin is chargeable, the absence of compunction with which he relates the changing of a sacred religious pilgrimage into something by no means unlike a mere filibustering raid on a great scale, add a charm to the book. For, religious as it is, it is entirely free from the very slightest touch of hypocrisy or, indeed, of self-consciousness of any kind. The famous description of the Crusades, gesta Dei per Francos, was evidently to Villehardouin a plain matter-of-fact description and it no more occurred to him to doubt the divine favor being extended to the expeditions against Alexius or Theodore than to doubt that it was shown to expeditions against Saracens and Turks."

PONTE ALLE GRAZIE (FLORENCE, LAPO)

PORTA ROMANA GATE, (FLORENCE, N. PISANO)

It was especially in the exploitation of biographical material that the Thirteenth Century chroniclers were at their best. Any one who recalls Carlyle's unstinted admiration of Jocelyn of Brakelonds' life of Abbot Sampson in his essays Past and Present, will be sure that at least one writer in England had succeeded in pleasing so difficult a critic in this rather thorny mode of literary expression. It is easy to say too much or too little about the virtues and the vices of a man whose biography one has chosen to write. Jocelyn's simple, straightforward story would seem to fulfill the best canons of modern criticism in this respect. Probably no more vivid picture of a man and his ways was ever given until Boswell's Johnson. Nor was the English chronicler alone in this respect. The Sieur de Joinville's biographical studies of the life of Louis IX. furnish another example of this literary mode at its best, and modern writers of biography could not do better than go back to read these intimate pictures of the life of a great king, which are not flattered nor overdrawn but give us the man as he actually was.

The English biographic chronicler of the olden time could picture exciting scenes without any waste of words. A specimen of his work will serve to show the merit of his style. After reading it one is not likely to be surprised that Carlyle should have so taken the Chronicler to heart nor been so enthusiastic in his praise. It is the very type of that impressionism in style that has once more in the course of time become the fad of our own day.

"The abbot was informed that the church of Woolpit was vacant, Walter of Coutances being chosen to the bishopric of Lincoln. He presently convened the prior and great part of the convent, and taking up his story thus began: 'You well know what trouble I had in respect of the church of Woolpit; and in order that it should be obtained for your exclusive use I journeyed to Rome at your instance, in the time of the schism between Pope Alexander and Octavian. I passed through Italy at that time when all clerks bearing letters of our lord the Pope Alexander were taken. Some were imprisoned, some hanged, and some, with nose and lips cut off, sent forward to the pope, to his shame and confusion. I, however, pretended to be Scotch; and putting on the garb of a Scotchman, and the gesture of one, I often brandished my staff, in the way they use that weapon called, a gaveloc, at those who mocked me, using threatening language, after the manner of the Scotch. To those that met and questioned me as to who I was, I answered nothing, but, "Ride ride Rome, turne Cantwereberei." This did I to conceal myself and my errand, and that I should get to Rome safer in the guise of a Scotchman.

"'Having obtained letters from the pope, even as I wished, on my return I passed by a certain castle, as my way led me from the city; and behold the officers thereof came about me, laying hold upon me, and saying, "This vagabond who makes himself out to be a Scotchman is either a spy or bears letters from the false pope Alexander." And while they examined my ragged clothes, and my boots, and my breeches, and even the old shoes which I carried over my shoulders, after the fashion of the Scotch, I thrust my hand into the little wallet which I carried, wherein was contained the letter of our lord the pope, placed under a little cup I had for drinking. The Lord God and St. Edmund so permitting, I drew out both the letter and the cup together, so that, extending my arm aloft, I held the letter underneath the cup. They could see the cup plain enough, but they did not see the letter; and so I got clear out of their hands, in the name of the Lord. Whatever money I had about me they took away; therefore I had to beg from door to door, without any payment, until I arrived in England.'"

Another excellent example of the biographic prose of the century, though this is the vernacular, is Joinville's life of St. Louis, without doubt one of the precious biographical treasures of all times. It contains a vivid portrait of Louis IX., made by a man who knew him well personally, took part with him in some of the important actions of the book, and in general was an active personage in the affairs of the time. Those who think that rapid picturesque description such as vividly recalls deeds of battle was reserved for the modern war correspondent, should read certain portions of Joinville's book. As an example we have ventured to quote the page on which the seneschal historian himself recounts the role which he played in the famous battle of Mansourah, at which, with the Count de Soissons and Pierre de Neuville, he defended a small bridge against the enemy under a hail of arrows.

He says: "Before us there were two sergeants of the king, one of whom was named William de Boon and the other John of Gamaches. Against these the Turks who had placed themselves between the river and the little tributary, led a whole mob of villains on foot, who hurled at them clods of turf or whatever came to hand. Never could they make them recoil upon us, however. As a last resort the Turks sent forward a foot soldier who three times launched Greek fire at them. Once William de Boon received the pot of green fire upon his buckler. If the fire had touched anything on him he would have been entirely burned up. We at the rear were all covered by arrows which had missed the Sergeants. It happened that I found a waistcoat which had been stuffed by one of the Saracens. I turned the open side of it towards me and made a shield out of the vest which rendered me great service, for I was wounded by their arrows in only five places though my horse was wounded in fifteen. One of my own men brought me a banner with my arms and a lance. Every time then that we saw that they were pressing the Royal Sergeants we charged upon them and they fled. The good Count Soissons, from the point at which we were, joked with me and said 'Senechal, let us hoot out this rabble, for by the headdress of God (this was his favorite oath) we shall talk over this day you and I many a time in our ladies' halls.'"

We have said that the writing of the Thirteenth Century must have been done to a great extent for the sake of the women of the time, and that its very existence was a proof that the women possessed a degree of culture, that might not be realized from the few details that have been preserved to us of their education and habits of life. In this last passage of Joinville we have the proof of this, since evidently the telling of the stories of these days of battle was done mainly in order that the women folks might have their share in the excitement of the campaign, and might be enabled vividly to appreciate what the dangers had been and how gloriously their lords had triumphed. At every period of the world's history it was true that literature was mainly made for women and that some of the best portions of it always concerned them very closely.

We have purposely left till last, the greatest of the chroniclers of the Thirteenth Century, Matthew Paris, the Author of the Historia Major, who owes his surname doubtless to the fact that he was educated at the University of Paris. Instead of trying to tell anything about him from our own slight personal knowledge, we prefer to quote the passage from Green's History of the English People, in which one of the greatest of our modern English historians pays such a magnificent tribute to his colleague of the earlier times:

"The story of this period of misrule has been preserved for us by an annalist whose pages glow with the new outburst of patriotic feeling which this common expression of the people and the clergy had produced. Matthew Paris is the greatest, as he is in reality the last of our monastic historians. The school of St. Albans survived indeed till a far later time, but the writers dwindle into mere annalists whose view is bounded by the Abbey precincts, and whose work is as colorless as it is jejune. In Matthew the breadth and precision of the narrative, the copiousness of his information on topics whether national or European, the general fairness and justice of his comments, are only surpassed by the patriotic fire and enthusiasm of the whole. He had succeeded Roger of Wendover as Chronicler of St. Albans; and the Greater Chronicle, with the abridgement of it which has long passed under the name of Matthew of Westminster, a "History of the English," and the "Lives of the Earlier Abbots," were only a few among the voluminous works which attest his prodigious industry. He was an eminent artist as well as a historian, and many of the manuscripts which are preserved are illustrated by his own hand. A large circle of correspondents—bishops like Grosseteste, ministers like Hubert de Burgh, officials like Alexander de Swinford—furnished him with minute accounts of political and ecclesiastical proceedings. Pilgrims from the East and Papal agents brought news of foreign events to his scriptorium at St. Albans. He had access to and quotes largely from state documents, charters, and exchequer rolls. The frequency of the royal visits to the abbey brought him a store of political intelligence and Henry himself contributed to the great chronicle which has preserved with so terrible a faithfulness the memory of his weakness and misgovernment. On one solemn feast-day the King recognized Matthew, and bidding him sit on the middle step between the floor and the throne, begged him to write the story of the day's proceedings. While on a visit to St. Albans he invited him to his table and chamber, and enumerated by name two hundred and fifty of the English barons for his information. But all this royal patronage has left little mark on his work. "The case," as he says, "of historical writers is hard, for if they tell the truth they provoke men, and if they write what is false they offend God." With all the fullness of the school of court historians, such as Benedict or Hoveden, Matthew Paris combines an independence and patriotism which is strange to their pages. He denounces with the same unsparing energy the oppression of the Papacy and the King. His point of view is neither that of a courtier nor of a Churchman, but of an Englishman, and the new national tone of his chronicle is but an echo of the national sentiment which at last bound nobles and yeomen and Churchmen together into an English people."

We of the Twentieth Century are a people of information and encyclopedias rather than of literature, so that we shall surely appreciate one important specimen of the prose writing of the Thirteenth Century since it comprises the first modern encyclopedia. Its author was the famous Vincent of Beauvais. Vincent consulted all the authors, sacred and profane, that he could possibly lay hands on, and the number of them was indeed prodigious. It has often been said by men supposed to be authorities in history, that the historians of the Middle Ages had at their disposition only a small number of books, and that above all they were not familiar with the older historians. While this was true as regards the Greek, it was not for the Latin historical writers. Vincent of Beauvais has quotations from Caesar's De Bello Gallico, from Sallust's Catiline and Jugurtha, from Quintus Curtius, from Suetonius and from Valerius Maximus and finally from Justin's Abridgement of Trogus Pompeius.

Vincent had the advantage of having at his disposition the numerous libraries of the monasteries throughout France, the extent of which, usually unrealized in modern times, will be appreciated from our special chapter on the subject. Besides he consulted the documents in the chapter houses of the Cathedrals especially those of Paris, of Rouen, of Laon, of Beauvais and of Bayeux, which were particularly rich in collections of documents. It might be thought that these libraries and archives would be closely guarded. Far from being closed to writers from the outer world they were accessible to all to such an extent, indeed, that a number of them are mentioned by Vincent as public institutions.

His method of collecting his information is interesting, because it shows the system employed by him is practically that which has obtained down to our own day. He made use for his immense investigation of a whole army of young assistants, most of whom were furnished him by his own order, the Dominicans. He makes special mention in a number of places of quotations due to their collaboration. The costliness of maintaining such a system would have made the completion of the work absolutely impossible were it not for the liberality of King Louis IX., who generously offered to defray the expenses of the composition. Vincent has acknowledged this by declaring in his prefatorial letter to the King that, "you have always liberally given assistance even to the work of gathering the materials."

ST. CATHERINE'S (LÜBECK)

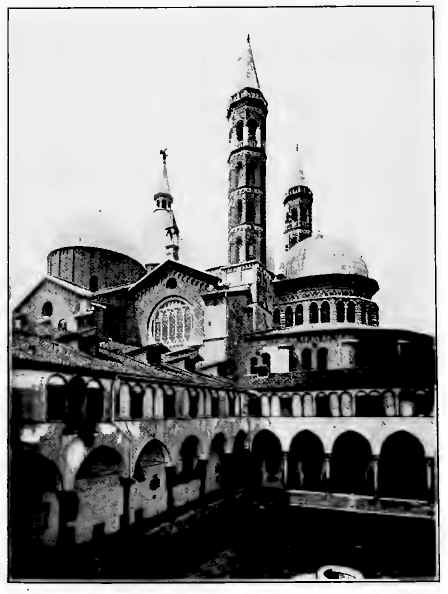

CHURCH AND CLOISTERS, SAN ANTONIO (PADUA)

Vincent's method of writing is quite as interesting as his method of compilation of facts. The great Dominican was not satisfied with being merely a source of information. The philosophy of history has received its greatest Christian contribution from St. Augustine's City of God. In this an attempt was made to trace the meaning and causal sequence of events as well as their mere external connection and place in time. In a lesser medieval way Vincent tried deliberately to imitate this and besides writing history attempted to trace the philosophy of it. For him, as for the great French philosophic historian Bossuet in his Universal History five centuries later, everything runs its provided race from the creation to the redemption and then on toward the consummation of the world. He describes at first the commencements of the Church from the time of Abel, through its progress under the Patriarchs, the Prophets, Judges, Kings, and leaders of the people, down to the Birth of Christ. He traces the history of the Apostles and of the first Disciples, though he makes it a point to find place for the famous deeds of the great men of Pagan antiquity. He notes the commencement of Empires and Kingdoms, their glory, their decadence, their ruin, and the Sovereigns who made them illustrious in peace and war. There was much that was defective in the details of history as they were traced by Vincent, much that was lacking in completeness, but the intention was evidently the best, and patience and labor were devoted to the sources of history at his command. Perhaps never more than at the present moment have we been in a position to realize that history at its best can be so full of defects even after further centuries of consultation of documents and printed materials, that we are not likely to be in the mood to blame this first modern historian very much. As for the other portions of his encyclopedia, biographic, literary and scientific, they were not only freely consulted by his contemporaries and successors, but we find traces of their influence in the writings and also in the decorative work of the next two centuries. We have already spoken of the use of his book in the provision of subjects for the ornamentation of Cathedrals and the same thing might be said of edifices of other kinds.