Полная версия:

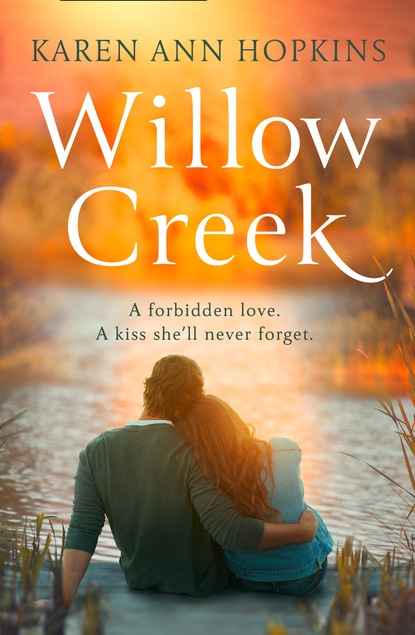

Willow Creek

I shook my head vigorously. “No, no. You don’t have to worry about that with me and Rowan. He’s just training the horses so we don’t lose the ranch. That’s it. I don’t even like him much.”

Momma looked at me with the arch of her eyebrows that signaled firm wisdom, making me catch my breath. “I hope that’s true, for your sake, and that we might be able to hold onto the ranch.” She pinned me with a steady gaze. “Mark my words, Katie. If that boy finds out his father and I were in a relationship before his mother came along, he might not finish the job. That’s a chance we can’t take.”

Her warning settled over me like a heavy winter blanket. I didn’t like secrets under the best of circumstances, but keeping something like this to myself wouldn’t be such a big deal if it weren’t for Rowan and his penetrating eyes. He probably thought my daddy was the bad guy, but in truth his own father was even worse.

I nodded reluctantly, agreeing, and glanced back up. I spotted Rowan coming from the barn with the saddle in his arms.

“Oh, great,” I mumbled, jogging down the porch steps.

“Wait,” Momma called out. She picked up the two glasses of lemonade and followed me down the steps. “He must be dying of thirst by now.” When I frowned back at her, she added, “The sins of the father don’t belong to the son. As long as you keep the relationship business-only, you’ll be fine, Katie. We’ll all be fine.”

I took the glasses without meeting her gaze. Of course, she was absolutely right. I needed Rowan to train the horses; that’s all I needed from him. Any flirty looks he might shoot my way meant nothing. He was probably a player, just like his ol’ dad. I’d heard stories of the Amish partying, dating non-Amish, and going wild before they finally settled down in their communities. That was probably what had happened with James Coblentz. He’d taken a fancy to my mom and had a little fun before he found an Amish woman to cook, clean, and warm his bed at night. I wouldn’t fall into the same trap as Momma.

As I approached Rowan, holding the glasses in my hands, I admitted to myself that it was a shame the man was once again off limits. He finally noticed me and set the saddle down on the fence railing. I tried not to look at his broad shoulders and slim hips, but that meant looking him in the eye.

When he saw the lemonade, he smiled and tipped his hat. His brows lifted and his eyes widened. He left Remington and shimmied between the fence railings to meet me.

I caught a whiff of his musky sweat mixed with horse hair and leather. When I looked up, shielding my eyes from the sunshine, he stepped closer. His tall frame blocked the sunlight and I suddenly ached for those strong, muscled arms to encircle me.

“You read my mind.” He gestured at one of the glasses of lemonade.

I held it out to him but before he took it, he abruptly kneeled in the dirt beside me. I dropped my gaze.

“Hey, girl, do you remember me?” Rowan ran his hands through my dog’s fur in the same gentle way

he touched Remington. “She must be getting on in years,” he commented, still petting Lady.

I nodded once, at a loss for words. Lady didn’t like anyone but Momma and me. The electric meter-reading guy couldn’t even climb out of his truck for fear of getting bitten. And here she was, after six years of not seeing Rowan, rolling onto her back and letting him rub her belly. She’d turned back into a panting, squirming puppy for him.

Staring at Rowan’s crouched form over my dog, I knew I was a goner.

Rowan finished off the lemonade with a swig and handed me the glass. “That was refreshing. Thank you.”

“Momma made it,” I said quickly.

Rowan smiled a little and grasped Remington’s lead line. The horse had been resting in the sun, eyes closed and head dropped. The slight touch on the rope connected to his halter brought him fully alert. His ears pricked forward and he turned to look at Rowan.

I set the glasses onto the ground and crossed my arms over the railing to watch Rowan lead the colt around the pen a couple of times. Occasionally he stopped Remington and turned him in tight circles. The horse moved in a willing way. He almost seemed a little tired.

When Rowan dropped the rope and said, “Whoa,” Remington slid to a stop, licking his lips. The mouth action showed that the horse was giving in to Rowan, trusting him as his master.

I cocked my head and studied Rowan’s movements. He walked around the horse with a casual demeanor that neither threatened Remington, nor made him feel that Rowan was a pushover. The man’s strides were free and easy, his posture loose. He crossed the pen with his head lowered most of the time, seeming to ignore the horse altogether. I wasn’t fooled. My trained eyes picked up Rowan’s subtle glances and his slightly cocked head and listening ears. He was always aware of where Remington was and what he was doing.

I tried not to notice Rowan’s athletic physique and the bulge of muscles where his shirt sleeves were rolled up. Suspenders slipped over wide shoulders, and dust stained the sweaty, cream-colored material. When he spoke to Remington, his voice was quiet yet firm. Even though it had to be over eighty-five degrees, a shiver raced up my neck when Rowan spoke my name.

“Katie, I think we’re ready for the saddle.”

I almost protested, wishing he’d give Remington a few more days of ground training, for Rowan’s own safety, but with twelve other colts to break, there wasn’t the luxury of time to go slow with the palomino. I nodded, giving Rowan the go-ahead to try the saddle again.

This time Rowan placed the pad and saddle down on the horse’s back at the same time. He probably didn’t want Remington to have much time to figure out what was happening. The longer a smart horse like Remington had to think, the more danger the trainer was in.

In a smooth action, Rowan pulled the girth under the belly and secured the tie strap. In an even quicker motion, Rowan slipped his boot into the stirrup and lightly swung his other leg over Remington’s back. A warm breeze lifted the horse’s white mane, bringing with it the scent of the grass that was curing in the hayloft. I breathed the sweet scent in deeply and then held my breath, waiting for Remington to explode.

Rowan sat deep in the saddle, slightly hunched, with his long legs barely touching Remington’s sides. He slid just the toes of his boots into the stirrups while he leaned over and rubbed the golden neck.

“There, boy. That’s not so bad, is it?” he asked in a coaxing voice.

When he made the same clucking sound he’d made earlier to get Remington moving off on the rope, I gripped the rail. Lady gave a low whine, as if she understood how temperamental the horse was and that Rowan was in danger.

The barnyard quieted; even the birds seemed to pause their singing to see what happened next.

Remington shifted his weight, spreading his legs further out to the sides, stubbornly not moving. Rowan made the noise again and this time, he brushed his boot heels into the colt’s sides. Remington surged forward awkwardly. His balance was off with the man’s weight straddling his back for the first time. Rowan lifted his hands, using his expertise to easily control his own balance as Remington trotted bouncily around the pen. Whenever the horse started to lose impulsion, Rowan urged him forward with clucks and his forward seat. I let out a breath and began to enjoy the training session. The horse listened to the man, speeding up and slowing down on cue. When Remington’s golden coat was slick and shiny with sweat and his breathing was heavy, Rowan sat back and said, “Whoa, boy,” with a firm voice.

Remington remembered the words and their meaning. He seemed relieved when he planted his four feet on the ground and immediately dropped his head to rest.

“I’m impressed,” I admitted.

“Strong-willed horses like this one need a job to do more than most. He wants to be a part of a team. He’ll make a great horse when we’re finished with him.”

That he’d said we’re made me wonder at his choice of words. After all, Rowan was the one training the horse, not me. I let the thought go. My arm was beginning to throb and I had to get ready for work if I was going to make my shift on time. I’d missed several days for Daddy’s burial, and although Billy had been more than accommodating with my time off, I didn’t want to push the restaurant owner’s generosity too far. Besides, Momma and I needed the money.

“How long can you stay today?” I asked.

Rowan looked at his watch and leaned back, resting his hand on Remington’s croup. “Our driver should be picking me up in about a half hour, I reckon. I have to work with the building crew this afternoon.”

I tried not to let the disappointment show on my face. I knew when I’d hired Rowan that he had other jobs to keep up with and that training the horses wouldn’t be his sole priority. I responded with as cheery a voice as I could manage. “All righty. Can you come back tomorrow?”

Rowan lifted the rope and clucked to Remington, waking him from his tired trance. He took a few steps to reach me at the fence and stopped again when Rowan said, “Whoa.”

“The schoolhouse benefit dinner is tomorrow night and I’m signed on to help some of the other men put up the tent and clean out the tie stalls for the horses.” He must have read the disappointment on my face, because he quickly added, “I can plan to come over after the auction and maybe even later today.” He glanced around. “Your barn and pen are well lit and it’ll be cooler at night.” He pursed his lips, frowning. “That’s something I really envy you of: electric lights at night.”

I grinned back but I couldn’t help asking, “Why don’t your people use electricity anyway?”

His spine straightened. “If I had a dollar for every time someone asked me that question—”

I cut him off. “Sorry, you don’t have to explain it to me.” My skin bristled with agitation that I’d been so stupidly forward. The Amish had their own culture and even though I didn’t understand half of why or what they did, their religion deserved respect like anyone else’s.

Rowan removed his hat and dragged his fingers through his thick, dark hair. An image of Momma and Rowan’s father kissing sprang to mind. I quickly looked down the driveway. Maybe it would have been better if Momma had never told me about her and James Coblentz. The idea of her romance with an Amish man was mind-blowing enough but the images dancing around in my head were downright disturbing. The only reason I could fathom that she’d shared a glimpse into her past with me was to make sure I didn’t make the same mistake with Rowan that she had made with his father. Momma had never been good at telling me what to do. Her parenting skills were much more subtle than that. By retelling the story of her disastrous relationship with an Amish man, she’d gotten the message across loud and clear. Even if my friendship with Rowan blossomed into something deeper while he trained the horses, it didn’t matter. He was Amish and therefore off limits.

“I didn’t mean that I didn’t want to explain it to you, just that it’s something I figured most people would understand by now.” His brow lifted and he managed a weak smile. “You know, there are hundreds and thousands of us, and our communities have spread to most of the States and Canada.”

“I hadn’t really ever thought about the Amish population before.” I shifted my gaze back to Rowan’s face.

“We don’t use electricity for several reasons but the main one is that it opens our homes up to the outside world through the electric lines.”

I scrunched my face, shaking my head. “That doesn’t make any sense. What about gas? I’ve heard your people use natural gas for lights and the stove, and to run your refrigerators.”

His smile disappeared and his lips thinned. “Just because it’s the way we do things, doesn’t make it perfect.” His mouth twitched and then broke out into a wide grin.

I snorted out a laugh and began to pivot away when he cleared his throat.

“Have you ever been to the benefit dinner?”

I shook my head. I’d been tempted on a few occasions but I was always working or doing something else, it seemed.

Rowan’s voice dropped lower and he leaned forward over Remington’s neck. The horse stepped sideways and I guessed he believed his resting session was over. “You should come. There’s good food, and we raise the money to pay for our teacher’s salary and our little school’s maintenance. There’s an auction at seven o’clock and everything from wooden furniture and crafts to doves and goats will sell. The quilt my Ma and the other ladies are sewing will be raffled off, too.”

“Sounds fun, but I have work tomorrow.” I pulled my cellphone from my back pocket, checking the time. “I’m running late for today’s shift. I have to go. I’ll tell Momma to leave the gate open tonight and tomorrow, so you can come on up and work with the horses after dark, if you have the time.”

“You won’t be here tonight?” Rowan’s voice was guarded, almost rough.

“I normally pull a double shift on Fridays. Sometimes I don’t get home until after midnight. It just depends on how busy the restaurant is.”

“I see.”

Rowan’s expression was tight and his eyes downcast. If I was a betting woman, I’d say he was disappointed that he might not see me for a couple of days.

I smothered my satisfied smile with my hand. “You’re doing a great job with Remington. He really is the worst of the bunch. After today, I’m hopeful that you might actually succeed and get the training done by sale day.”

He tipped his hat. “Oh, there’s no doubt I’ll have them colts trained up in time.”

His confidence caused my muscles to ease and my nerves to quiet. It would still be a small miracle, but the Amish man was determined, making it a little less of a long shot.

Lady led the way back to the house when Rowan called out, “If you don’t mind me asking, where do you work?”

I paused to look back. “At Billy’s Diner and Saloon. Have you ever eaten there?”

“Can’t say I have.”

“I’m sure your standards are fairly high, with all I’ve heard about how delicious Amish cooking is, but the steak sandwich, with a baked macaroni cheese side, is really good.”

“Maybe I’ll check it out sometime,” he replied.

I turned away and kept walking. I’d never seen any Amish people in Billy’s before. Someone had said it had to do with the word saloon in the restaurant’s name ‒ and that the Amish didn’t frequent places that sold alcohol.

As I climbed the porch steps, my heartrate sped up. I had a feeling Rowan would be true to his word. He’d be the first Amish person to dine in the restaurant and, if my instincts were correct, he wouldn’t wait too long to check out Billy’s Diner.

Six

Rowan

When I closed the door behind me the smell of baked goodness assailed my senses. I breathed in deeply and looked around. The kitchen was empty and I let go a sigh of relief. I wasn’t in the mood for conversation with family. It had been a hot afternoon on the roof of a garage the crew had built for a fellow in town. The beating sun had burned the back of my neck and the side of my temple ached where Martin had dropped a board on my head as I’d climbed up the ladder behind him. I rubbed the throbbing spot and crossed the room to the refrigerator. I grabbed a cold bottle of water from the top shelf and sat down at the table. A dozen pies were lined up and cooling on the counter. The breeze stirring the curtains above the sink was still warm, even though the sun had dropped low in the sky. I still had to feed the horses and calves.

I wasn’t surprised that Ma wasn’t around. She’d told me that morning that she would be visiting Martha Miller this evening ‒ something about needing a few more stitches on the raffle quilt to make it perfect ‒ and that Father would take her over with the buggy. He wanted to see Tim’s new team of Belgian horses anyway. There was a small piece of paper on the table. I reached out and dragged the note over with my fingers.

Your dinner is in the fridge. Nathaniel came along with us but your sister stayed home.

Please keep an eye on her. I don’t want her getting into any mischief. Mother

I leaned back in the chair. I’d seen the plate with the pork chop and potatoes when I’d fetched the water but I wasn’t hungry and had ignored it. I cocked my head and listened. The house was quiet, except for the dull ticking sound of the old clock on the fireplace mantle in the adjoining room. Where was Rebecca?

Like horses breaking from the gate in a race, my heart began pounding. I stood up and hurried into the hallway, glancing into the parlor first. The sofa and chair were empty. The room was shadowed and only a small strip of the floor was lit by the low, buttery light shining in through the window. I passed the painting of the white farmhouse in the snow, and the scripture verse in the corner popped out at me:

“But godliness with contentment is great gain. For we brought nothing into the world, and we can take nothing out of it.”1 Timothy 6:6-7

Even though the house was stuffy, a chill penetrated the skin on my arms. I took two steps at a time as I climbed the staircase to the second floor. Mother and Father had expected me to arrive home sooner. The mischief they worried Rebecca might get into had to do with their idea of her rebellion and had nothing to do with her troubled state of mind. After our conversation about what had become of poor Lucinda, I was more afraid that Rebecca was thinking about death and its promise of freedom from our restrictive world.

I stopped in front of Rebecca’s bedroom door and held my breath. The door was shut. Slowly I turned the knob and pushed. The last rays of daylight spilled through the west-facing window. Beneath those splendid rays, I found Rebecca sitting on the floor. Her back was to me and her head was bent. She was very still except for an occasional bob of her head. I hadn’t relaxed enough to take a proper breath. Careful not to startle my sister, I stepped lightly. It wasn’t until I reached the warmth of the fading sunshine that I saw the white plastic plugs in her ears. They were connected to thin wires that draped around her neck, attaching to a small technology device. It looked like a cellphone, but smaller.

I was close enough to hear the muffled beat of music and realized she was listening to a song. I knelt beside her and leaned over. Rebecca couldn’t hear me and her eyes were closed. Her mouth was parted and her lips mouthed silent words. The tight paleness of her face made me shiver, but it was what she was holding in her hands that made me shrink back, rocking onto the heels of my boots.

In one hand she held a drawing pencil and in the other a sketch book. I forced myself to take a closer look at the picture Rebecca had drawn. It was of a girl ‒ or maybe a young woman ‒ with long hair, blowing across her eyes. Her neck was thrown back, raising her face to a dark sky. The girl was naked with a bent leg and her long hair hiding the lower part of her body. A breast was exposed. The fact that she’d drawn such a scandalous picture barely penetrated my mind. It wasn’t the girl’s nakedness that was shocking; it was the look on her face that held me in a stony grip. The mouth twisted open grotesquely in a scream that I was sure if I closed my eyes I would be able to hear. Then I noticed the girl’s fingers digging into her thigh and the blood drops dribbling down her skin. The girl’s tightly curled toes completed the tortured image. My gaze quickly lifted to the paintings decorating the pale blue walls.

Rebecca was a self-taught artist. She began doodling as a child. All she’d ever wanted for her birthday presents was painting supplies, and Father had even let her use the back side of the toolshed as a canvas for her ever-changing color experiments. Early on, everyone had praised her for her growing abilities, but over time, Mother and Father became annoyed by the increasing time she spent painting, time that took her away from her many tedious chores.

Now, as I looked at her creations, I suddenly realized just how gifted my sister was. There was a picture of Rebecca’s round-barreled black pony standing knee deep in lush, green grass. Butterflies of all colors and sizes dotted the landscape. Wild chicory added blue splashes here and there in the pasture. Another painting captured the friendly warmth of the family farmhouse and red barns surrounded by hills and forest. The picture above Rebecca’s bed was of a brilliant red sunset over a cornfield. All of her artwork was expertly painted and beautiful to behold. Even the painting she’d done in the downstairs foyer, with its lonely house on the snowy hill and the melancholy Bible verse attached, was still striking.

But this newest drawing grasped in her hands was something altogether different. The black and charcoal grey strokes were harsh and the image of the pained girl, disturbing. If this was a glimpse into Rebecca’s soul, she was doomed.

This drawing was a cry for help if I ever saw one. I reached out and tapped her shoulder. She jumped up and slammed the sketchbook closed. Her gray eyes were wide and surprised.

She pulled the plugs from her ears and groaned, “Why are you sneaking up on me, Rowan?”

The hostile look of betrayal aimed at me made me take a step back. Annoyance prickled my insides. “If you didn’t have those things in your ears you would have surely heard me enter the room,” I shot back.

Rebecca glanced down at the white ear plugs and then clenched them in her balled fist. “Are you going to tell Da and Ma?” she asked.

I shook my head. “Of course not.”

Her shoulders dropped and a small smile tugged at the corner of her mouth before she turned back to her writing desk. She opened the drawer and pulled out a Bible. I inclined my head, watching curiously as she opened the book and set the slender device and the plugs into an opening she’d carved away from the pages.

A short gasp bubbled up from my throat. “Are you kidding me? You chopped up a Bible to make a hiding spot for your phone?”

“It’s not a phone ‒ just an iPod.” She glanced back over her shoulder. “You listen to music with it. That’s all.”

I rubbed my forehead vigorously. “I thought you were going to try to behave yourself, Rebecca. Father and Mother are on to you, and now the bishop is involved. You’re treading in dangerous waters.”

Rebecca faced me, her arms crossed. She leaned against the desk in a casual way that most people would have found disrespectful. When she was in this kind of mood, it unnerved me the most. Instead of looking back with her usually sad, desperate eyes, she glared at me. Her drawn features were filled with combative tension. I swallowed and braced for her anger.

Her voice was calm and quiet when she spoke. “There’s nothing wrong with listening to music while I draw. If I weren’t Amish, no one would even notice, let alone think to punish me.”

I plopped down on the edge of her bed and stared at the wooden floor. She was absolutely right, but that didn’t matter at all. Because we were Amish, our ways were different to the outside world. Rebecca understood that, so there was no point in arguing with her.

“You’re smarter than this. If it really is your intention to leave the community, then do it the right way ‒ with a sound plan.”

Rebecca’s eyes glowed. “You’re going to help me?”

I inhaled sharply. “If that’s what you really want, yes, I’ll help you. But you have to be patient. It’s going to take some time to sort things out.”

“What things?” Her eyes were as wide as saucers as she stood up straight and tall.