скачать книгу бесплатно

‘I’m like so –’ she made a face of horror and despair, a mask of tragedy and abandonment ‘– when I even like listen to you, you know what I mean? It was like this one time, at my friend’s house, you know, it was just like …’

‘You don’t have to like listen,’ Nick said.

‘Yeah, but I can’t help it, you know, I’m stuck in here.’

The door opened, and there was the eleven-year-old. He had been dressed by his mummy. He wore an ironed white short-sleeved shirt and blue trousers; his shoes were black lace-ups. He himself wore a cheerful, open expression, his black hair cut short at the back and sides, sticking up somewhat on top. Behind him was Mrs Khan, smoking.

‘Hi, kids,’ she said. ‘Having a good time? This is Basil. That’s Anita, and that’s …’

‘Nick,’ said Nick, and ‘Nathan,’ said Nathan.

‘That’s right. You know Mrs Osborne, don’t you? Have you met Basil before? He’s not in your school yet, are you, Basil?’

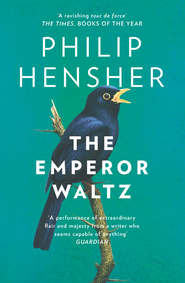

‘No, Mrs Khan,’ Basil said. ‘But I’m in the same orchestra as Anita. She plays the violin and I play the cello, though I’m only in the seventh desk back. We’re rehearsing Dvo

ák’s Eighth Symphony and the Emperor Waltz at the moment. The cello’s not really my main instrument, though. My main instrument’s the organ, but you can’t play that in orchestras apart from a few pieces. For instance, did you know Mahler’s Eighth Symphony has a part for an organ?’

‘I never knew that,’ Mrs Khan said, puffing on her cigarette. ‘That you were in the same orchestra as Anita. We must have a word with your mum, and then we can pick you up together rather than both turning out every week. That would save a lot of effort.’

‘Oh, it’s not an effort for Mummy,’ Basil said. ‘She says she enjoys the drive and I’m happy to be with her as much as possible, since the divorce, you know.’

Nick and Nathan exchanged incredulous glances of joy.

‘Oh, yes,’ Mrs Khan said, with an air of distaste. ‘Of course. Well, I must be getting back downstairs. There’s lots of food there, on the tray, look – my daughter and these two haven’t started it yet. I’m happy to see she has some manners still. If there’s anything else you need, just come downstairs. Bina’s cooking in the kitchen and she’ll help you out, help you to find anything. There’s some dessert, which she’ll bring up when you want it, it’s her special dessert, you’ll love it. You’d make everyone so happy if you ate the salad, too, kids. Well, I live in hope. See you all later.’

She left, closing the door.

‘Is this your father’s study?’ Basil Osborne said. He went round the room, looking in particular at all the books. ‘What do you think of the Emperor Waltz, Anita? It’s hard, isn’t it, harder than you think it’s going to be, but it’s satisfying when you get it right. I didn’t think I knew it, but I’d heard it before, somewhere. I know you, I’ve seen you a lot, but we’ve never said hello or anything like that.’

Anita was looking at him with disbelief.

‘So, Basil,’ Nick said heavily. ‘You play the organ.’

‘Yes, that’s right,’ Basil said. ‘I don’t have one at home, of course! I have to go and practise it in St Leonard’s Church, you know, the one up by the bus terminus. They let me come in on Tuesdays and Thursdays after school. Shall I sit here?’

‘Is it a big organ?’ Nathan said. ‘Do you like a big organ, Basil?’

‘Well, I’ve seen bigger organs, perhaps in cathedrals,’ said Basil. ‘But I’ve never played a really big one, I’ve only played on quite medium-sized organs, like the one in St Leonard’s. Is that food for us? Golly. It looks delish. Can we start on it or are we waiting for someone?’

‘Does it give you a lot of pleasure,’ Nick said ‘When you sit on a really big organ.’

‘Well, I don’t know that the size of the organ makes all that much difference,’ Basil said. ‘But I wouldn’t know. It’s true that even a moderate-sized one, when it’s going at full tilt, can be really exciting.’

‘So when you see a big organ,’ Nathan said, ‘I bet you can’t wait to sit on it.’

‘I don’t know that that’s really what organists think,’ Basil said, puzzled.

‘Oh, shut up,’ Anita said. ‘They’re being horrible, don’t pay any attention. Do you want some food? There’s plenty. That’s like lemon squash or you can have some Coke. There’s some like orange juice as well.’

Basil scrambled up from the beanbag and started filling his plate with food. It was as if he were in a race and might end without enough.

‘Take your time, man, take your time. Ain’t no ting,’ Nathan said.

‘You talk like black people do,’ Basil said gleefully, with an air of discovery. ‘There’s a boy in my class called Silas who comes from Jamaica, at least his parents do, he was born here, and sometimes he talks like his grandmother talks and he sounds just like you do. This looks really good, I like everything here. It was nice of your mother to make all this food specially for us.’

‘Yes, she knew how to make food that appeals to people who talk like a boy called Silas’s grandmother,’ Anita said. ‘Ah, Basil, you make me laugh, you really do.’

‘That ain’t true,’ Nick said. ‘Do I look I’m laughing, man?’

‘True that,’ Anita said, in Nick and Nathan’s style. Then she went into hostess mode. ‘Take your plate and sit down, Basil – there’s plenty of food, you can go back for more later. And some squash? Or Coke? There’s more downstairs if we finish this bottle.’

‘Like I say, man, take your time, ain’t no ting,’ Nick said.

‘Skeen, man,’ Nathan said. ‘Is it time to get wavey, man?’

‘Because Anita, that OJ, that Coke, that lemon squash and shit, well, I look forward to that, but there is something that you can put into those things to make them a less long, alie?’ Nick said.

‘I have literally less than no idea what you’re talking about,’ Anita said. ‘Anyway.’

‘Anita,’ Nick said. ‘Have you got any vodka that we can maybe put into the OJ?’

Anita looked from one to the other; she did not look at Basil, who had a samosa in hand and was, frozen, examining them all with interest. ‘Have I got any vodka?’ she said.

‘Vodka, yeah,’ Nathan said. ‘I know you do, girl.’

‘Is there anything else with your banter? Some like rum for the Coke or some gin for the lemon squash and shit or anything else completely random, you know what I mean?’

‘Oh, man, who’s the fool now, bro?’ Nathan said.

‘Well, I don’t know about that,’ Basil said. ‘I don’t think it’s a very good idea if your parents come upstairs at the end of the night and you’re all stinking of booze and can’t get up because you’re so drunk. They’ll smell it on you straight away. I could always tell when my daddy had been drinking because you could smell it on him, even the next morning, and he always said, Never again.’

‘And I suppose he did, though?’ Anita said.

‘Yes, he certainly did, sometimes in the same evening as the morning when he’d said, Never again or sometimes the next day. That was certainly a pie-crust promise.’

‘That was what are you even saying?’ Nick said.

‘That was a pie-crust promise, I said,’ Basil said.

‘What the fuck is a pricrust promise?’ Nathan said.

‘Not pricrust, pie-crust,’ Basil said. ‘It’s like the crust of a pie. Easily made, easily broken. Have you never heard that before?’

‘No, I ain’t never heard nothing like that before, man,’ Nick said. ‘Did you hear it when you were sitting on some massive organ, you might have misheard somewhat, man.’

‘Yeah, you so pricrust,’ Nathan said to Nick. ‘Easy to break, you are.’

‘So, boys,’ Anita said. ‘I’m not going to give you rum, because, you know, he’s right, it smells when the parents like come upstairs at the end of the evening? And gin less so but still it smells in the room and they’re definitely going to come in in some like totally random way and they’re going to like smell it? But vodka, that’s cool, we can put a little Mr V in our Mrs OJ and they won’t smell that. I’ve done that before? Like this one time at like my friend’s house, this is my friend Alice, we got like so wasted, and no one could tell, though her mum, the next day … We can do that, sure.’

‘I’ve never had vodka,’ Basil said, with the air of a reminiscing old colonel. ‘I’ve had a glass of champagne at my uncle’s wedding, when he got married to Carol, that’s his second wife, and once Polly, who’s my daddy’s girlfriend, she let me taste a bit of her margarita –’ and as Anita left the room, he turned to Nathan to go on ‘– because she likes making herself cocktails before dinner and I was there one night on a Saturday and my mummy was supposed to pick me up, only she thought that my daddy was supposed to bring me over, and I was still there when Polly had made her margarita and was putting their dinner in the oven – they get readymeals from Marks & Spencer, my daddy says Polly can’t cook and they like different things. I didn’t know,’ Basil went on confidingly, turning from Nathan to Nick, as Nathan, open-mouthed with disgust, got to his stockinged feet and followed Anita out, ‘I didn’t know about the margarita, whether I liked it or not, it was really strange. I don’t know what was in that, it was more of a mixture. But I’ve never had vodka. Oh, and once this boy in our class brought a can of beer to school and we all had a taste, I really don’t know why people like that, it was horrible.’

‘Yeah, you talking to yourself, man,’ Nick said. ‘I don’t know why you think anyone in this room even listening to what you

4. (#ulink_276dc819-6655-544a-94fd-5366dee1e346)

‘Well, that is kind of you,’ Vivienne Osborne was saying. ‘Just a very weak one. I’ve been so looking forward to this, I can’t tell you – I’ve had such a week at work.’

‘I do like your blouse,’ Shabnam Khan said.

‘It’s new, actually,’ Vivienne said. ‘I bought it only yesterday in Marks & Spencer – I shouldn’t say, but we all do, don’t we? It’s such good quality, and much better than it used to be, I mean from the point of view of fashion. You really wouldn’t know sometimes that it wasn’t from some Italian designer in Bond Street.’

‘What do you do, Vivienne?’ Charles Carraway said.

‘Me? I teach economics at one of the London colleges – you won’t have heard of it, I won’t even embarrass you by asking you.’

‘Try me,’ Charles Carraway said drily.

‘Oh, I shall, I shall,’ Vivienne said, with a lowering of her head, a glance upwards with her eyes that dated her to the early 1980s. She had seemed, initially, confused and unprepared as she had come in, handing coat and umbrella and glimpsed son over to Shabnam as if she had thought that Shabnam might be the housekeeper named Bina. Now she appeared to have resources of flirtatiousness, directed for the moment at Charles Carraway. ‘It’s called London Cosmopolitan University – people say it sounds like a cocktail. So you haven’t heard of it and now we can move on.’

‘I think I do know the name,’ Charles said. ‘Is it in Bethnal Green?’

‘Close,’ Vivienne said. ‘Oh, thank you so much, a lovely weak gin and tonic. Perfect. No, we’re in Fulham, actually. But I’m thrilled that you’ve heard of it. Thank you so much –’ she gestured with her drink, which spilt a little ‘– for asking me. I’ve just recently been going through the dreaded breakdown-and-separation-and-divorce from my husband,’ she explained, turning to Caroline Carraway and making quotation marks in the air, ‘though, Heaven knows, there wasn’t much to dread about that, it was really quite a relief in the end. We had a long period of not getting on, then of him moving into the spare bedroom, then of spending time avoiding each other in the house, I think he ate at the Chiswick Pizza Express every night for a month, and then his girlfriend, who I wasn’t supposed to know about, moved to a slightly larger place and he decided to move out. It was really not just a relief but a real pleasure for Basil and I when my husband moved out. That would have been two years ago. But nobody asks a divorced woman with a great lump of a son out for dinner. This is so kind of you – I mean to make the most of it. And you must come round to mine for dinner too! Very soon. Single women can entertain and make a success of it, I mean to show you. You have a son, don’t you, Caroline?’

‘They’re upstairs,’ Caroline said. ‘Actually, there are two. They’re twins. Do you like it, there, at the Cosmopolitan University?’

She had tried, apparently, to say the name of the university without altering her tone; she had almost succeeded.

‘It is a silly name, I know,’ Vivienne said. ‘But they decided when they turned into a university to appeal to Asian students, students from Asia I mean, which was very forward-thinking of them, and now we’re all quite used to the name and hardly notice how silly it is any more. Well, it would be nicer if my ex-husband, soon-to-be-ex husband, no, really ex-husband now, of course, didn’t also work there, so I see him all the time and occasionally have to deal with him. He’s the registrar. So I’m looking for another job, somewhere else.’

‘It shouldn’t be hard,’ Michael Khan said. ‘Economists must be so in demand everywhere, these days, with things in the shape they’re in.’

‘Oh, thank you, thank you, but I’m not really that sort of economist,’ Vivienne said. ‘But it’s nice of you to say so. The thing is, after my husband left, it was really an immense relief. For Basil, too – Basil’s my son, Shabnam – Shabnam? It is Shabnam, isn’t it? You get good at names in my trade. Now, you know, this is an awfully unfashionable thing to say, but I really am enjoying being single, for the first time in years, decades, since I was fifteen perhaps, maybe ever! Anyway. Basil, too. Well, that is kind of you – I will have another drink, a very weak one, though, please, Michael.’

‘And an olive?’ Caroline said, passing over a ceramic bowl. She herself would not touch olives, death to the digestion, straight to the hips.

‘Thank you,’ Vivienne said, hovering and then judiciously taking one, as if she were judging produce in the market. ‘The truth of the matter is that

5. (#ulink_25951478-b417-5116-8164-bb59ea59aaf9)

‘Give it me in my Coke,’ Nathan said. ‘I don’t like that OJ, I drink Coke, me.’

‘Oh, my God.’ Anita took her half-full bottle of Stolichnaya vodka and poured an inch into a glass. ‘Vodka and Coke, that’s a terrible drink, that’s a really like thirteen-year-old’s drink when you’ll drink anything? Oh, I forgot, you are thirteen. And you, Nathan, what do you want?’

‘I’m Nick,’ Nick said. ‘That’s Nathan. Can’t you tell us apart?’

‘No, I can’t remember,’ Anita said. ‘What do you want?’

‘I’m going to have some vodka with OJ,’ Nick said. ‘That’s how you drink vodka, fool.’

‘I’m drinking vodka how I like it,’ Nathan said. ‘Fool.’

‘And you, Basil?’ Anita said. ‘Do you want to try some?’

‘It’s not horrible, is it?’ Basil said. ‘But just a little bit, so I know what the taste of it is like. I don’t want to become addicted or an alcoholic. But just a little bit and mostly orange juice. It won’t taste horrible, will it, Anita? Promise?’

‘Promise,’ Anita said. She poured an inch or so into Basil’s glass; she dropped ice cubes into his drink; she took a slice of lemon from a plate where it had been sliced into half moons; she filled the glass with orange juice from the cardboard carton. She handed it to him, and Basil drank immediately from it, as if getting the drinking of poison over with.

‘Steady, mate,’ Nick said.

‘Mummy always said that I ought to be given the taste of alcohol when I was younger, like Granny giving me a glass of champagne to make sure what it tasted like, because she said if I did – if I did I would get used to it and never have a problem with it. But Mummy said that Granny had done the same with Daddy. My daddy does drink a bit too much, I think, and when he’s been drinking, he has a tendency to light a cigarette or two, and that I just don’t understand one bit. You know what? I really quite like this. You can’t taste the vodka, though I don’t know what vodka tastes like, it just makes the orange juice taste really orangey. I could drink this all night. Does it do the same for your Coke, Nathan?’

‘I’m Nathan, fool,’ Nathan said.

‘Yes, I know,’ Basil said, puzzled. ‘That’s what I called you.’

Nick brought his knees almost to his chest with laughing. ‘Ah, he got you, man,’ he said, punching himself on the breastbone. ‘He got you. He said does it do the same for your Coke, Nathan, and you said I’m Nathan, fool, though he’d said Nathan, and you weren’t listening, man, you just know everyone’s going to call you Nick when they mean Nathan, you don’t own your name, man, this wallad, he owned you, wallad.’

‘The fuck up,’ Nathan said. ‘Ain’t amusing, wallad.’

‘That was pretty funny,’ Anita said. ‘He was so like cross, too? Do it again, do something funny, Basil.’

‘Well, I can do this,’ Basil said, and he pulled a face, his long lower lip out and his hands to his ears. But they looked at him and did not laugh. ‘Most people think that’s awfully funny, it’s my best face. I can’t be funny to order. I didn’t know I was being funny when I called him Nathan, because that’s his name anyway. Mostly it isn’t funny when you call somebody by their right name, so I don’t know why it was funny then. I like this drink, Anita, can I have another one?’

‘Take it steady, wallad, take it steady,’ Nick said. ‘That stuff is lethal, man. You going end crunk in five minutes you take it like that. Wavey, man, wavey.’

‘This ain’t bad,’ Nathan said. ‘Vodka/Coke, it’s sick, man. But I want something better, me, I want me a safe ting.’

‘Happz, man?’ Nick said, and made that gesture with his hands, a casting down of a viscous liquid, like Spiderman throwing jizz to the floor.

‘Alie,’ Nathan said. ‘I want me a safe ting.’ He wailed upwards as if in song.

‘Oh, my God,’ Anita said. ‘Keep it down or my dad’ll be up and he’ll like know you’ve been drinking, it was like at my friend’s house once, this is my friend Alice, I was just saying, we brought in this bottle of voddie and asked her mum just for a couple of cartons of Tropicana, and we like just, this is like four of us, me and Alice and Katie and Alice, the other Alice who we don’t really like that much, you know what I mean, but we were like getting out of it, and making all this like noise, you know what I mean, and suddenly there’s this amazing noise on the stairs, like a herd of buffalo coming upstairs, and it’s like Alice’s dad telling us to keep it down, but we managed to like shove the bottle under the bed just before he came in so that was just about OK.’

‘I want me a safe ting,’ Nathan said, still crooning what he had said, but more quietly.

‘Here it is,’ Nick said, standing up. His jeans hung down below his buttocks, showing a pair of red 2XL underpants; he reached down and from his back pocket extracted the small bottle labelled Jungle Juice.

‘Well, you’re not going to get at all drunk on a tiny bottle of that,’ Basil said, in a mature, scoffing voice.

‘You don’t be drinking it, man,’ Nathan said. ‘You watch and learn, my friend, watch and learn.’

‘I can’t believe that you’ve brought some poppers out with you. It’s like we’re in a gay disco circa 1996,’ Anita said. ‘Where did you get that, your boyfriend?’

‘Fuck you, man,’ Nick said, giving it to Nathan. ‘Ain’t no gay ting.’

‘That is like so gay,’ Anita said.

‘It’s safe, man,’ Nathan said. He grinned; he unscrewed the lid of the bottle. He placed one forefinger against one nostril, and put the bottle to the other where he sniffed noisily. He put another forefinger to the other nostril, and sniffed in the other nostril. He clamped his thumb to the top of the bottle, and handed it to his twin. Nick did exactly the same, going from right nostril to left.