Полная версия:

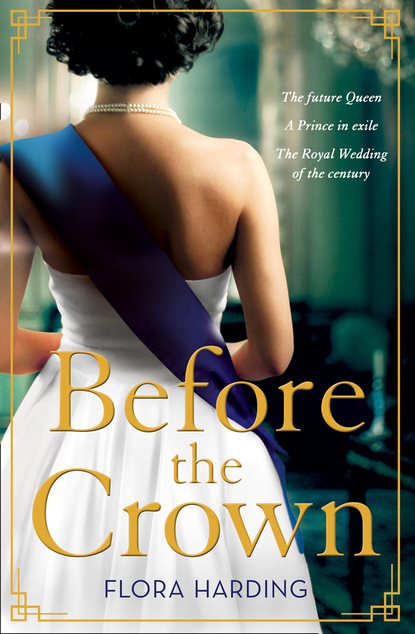

Before the Crown

‘Did you envy them?’

‘Not really. We were just curious. It’s hard to imagine what life is like for other people, isn’t it? Probably those children were walking past and wondering what it was like to live in a palace, but for us it was just the way things were. How they are.’

‘You’re lucky,’ Philip says, and she smiles faintly.

‘It doesn’t always feel that way. I know how privileged I am, but it does come at a price. I don’t have a choice about the life I get to lead.’

He looks down at her. ‘What would you choose if you could?’

‘Oh … nothing exciting. Just to live in the country with dogs and horses.’ She sighs a little. ‘I suppose you think that’s very dull,’ she adds, flushing a little.

A smile twitches the corner of his mouth. ‘Well, it’s not what I would choose, I have to admit. But if it’s what you want …’

‘I might want it but I’m not going to get it,’ Elizabeth says. ‘I might have been able to if Uncle David had done his duty, but he chose to put his personal feelings above that. Papa has had to pay the price for that decision, and I will too. Of course there are worse fates, but no, I don’t always feel lucky.’

Philip has his hands jammed into the pockets of his tweed jacket. ‘Actually, I was thinking about your family,’ he says. ‘About how close you are. Your parents, your sister. It’s been very nice for me to see that. I do envy you that.’

‘Yes, I am lucky in my family,’ she acknowledges, her face softening as she thinks of her beloved father, her bright, charming mother, and Margaret, so quick and so talented, so funny and spirited. Too spirited, sometimes. ‘Of course, Margaret and I have our moments, but I suppose all sisters have those.’

One of the dogs has dropped behind as it determinedly investigates some scent. Elizabeth turns and whistles for it, and after a moment, the dog grudgingly leaves the smell and trots towards them.

‘Jane,’ Elizabeth says fondly. ‘She’s getting on now and she likes to do what she wants. She’s the matriarch,’ she explains, glancing around at the corgis. ‘That’s her daughter and granddaughter … and over there is her great-granddaughter.’

Why is she talking about dogs? Philip can’t possibly be interested. She is just putting off the moment.

The water is dripping from the peak of his cap and the shoulders of his jacket are spangled with rain. She has been enjoying the walk but he must be soaked, she realises with a guilty look. ‘Shall we turn back?’ she asks.

Chapter 10

Philip is glad to agree. There is rain trickling down beneath his collar and his hands are frozen. He has never thought that he would remember with nostalgia those sweltering days aboard Valiant after the Chinese stokers jumped ship in Puerto Rico. Stripped to their shorts, stinking and sweating, he and his fellow midshipmen had to shovel coal into the ship’s furnaces all the way to Virginia and he had dreamt of a cold, wet winter day.

No longer.

‘You have sisters, don’t you?’ Elizabeth asks after a moment. ‘Are you close to them?’

She doesn’t ask about his parents. She must know that they have lived separate lives for many years.

‘I wouldn’t say close. I’m the baby of the family and my sisters are all much older than I am. They’re very … boisterous.’

In his memory, his ears ring with the noise his sisters create when they are all together. They’re all restless movement, jumping up and down, and swirling their skirts, a mass of swooping scented kisses and talking over each other and shrieks of laughter. Their conversation is a vibrant mixture of English, French, and German as forgetting a word in one language they would switch to another and then carry on in that until they went off at a tangent and into a new language that for some reason seemed better suited to it.

‘I’m very fond of all of them,’ he says. ‘Especially Cecile. She was killed in an air crash in 1937.’

‘What a tragedy,’ Elizabeth says.

‘Don, her husband, and my two nephews were with her. They were coming over here to a wedding. Cecile was heavily pregnant.’ A muscle jerks in Philip’s cheek. ‘She gave birth on the flight, perhaps even during the crash. The baby died with her. It never had a chance to live.’

‘I’m sorry.’ Elizabeth’s voice is so quiet that Philip barely hears her. He is remembering the sound of the gun carriages laden with coffins trundling over the cobbled streets of Darmstadt. He was sixteen. He flew to Germany from Gordonstoun and followed the coffins with his brothers-in-law in their Nazi uniforms, Uncle Dickie a row behind. Philip’s memories are blurred but he remembers his uncle’s hand on his shoulder during the funeral. He remembers the heavy tread of feet, the silent crowds watching. The sullen sky spitting sleety pellets of ice. The occasional stiff-armed salute and murmurs of ‘Heil Hitler’.

The yawning disbelief and horror: that could not be Cecile with her dancing eyes and burble of laughter shut up in that box.

He swallows down the memories. What is the point of wallowing in them? What’s done is done.

‘Margarita, Dolla – that’s Theodora – and Sophie – we call her Tiny – are still in Germany.’ Philip’s voice is even. All three were married to senior German officers. ‘For obvious reasons, I haven’t seen them for a while.’

‘That must be difficult for you.’

Philip isn’t going to admit to finding anything difficult. Isn’t that what Gordonstoun and the war has taught him? You get on with what you have to do. You don’t wring your hands and complain about your lot.

‘The war is difficult for everyone,’ he says almost curtly. ‘We are not the only family divided by war.’

Elizabeth glances at him. ‘I know,’ she says coolly. ‘My grandfather and Kaiser Wilhelm were cousins.’

The Great War had taught the British royal family to be chary of their German relations. They had changed their name to Windsor and insisted that the Battenbergs, descended from Queen Victoria and British to the back teeth, forfeit their princely title.

‘Your sisters’ German husbands will be your biggest handicap,’ Uncle Dickie warned him. ‘Distance yourself from them as far as possible.’

Why should he distance himself even further from his own sisters? God knows he has little enough family life to look back on, Philip thinks bitterly. His father is in Monte Carlo, his mother in Athens.

‘I see now why you think I am lucky,’ says Elizabeth. The wind is slapping the ends of her scarf against her chin and she wrestles with the slippery material as she attempts to retie it. ‘And I am. I have a family and a home.’

‘I haven’t had a home since I was nine,’ Philip is appalled to hear himself say, and he scowls, hunching his shoulders against the cold. He can feel her clear eyes on his profile and cringes inwardly, sure she has heard the bitterness edging his voice.

‘Is that when you were sent to school?’

‘Yes,’ he says stiffly, still ashamed of what he let slip. He is supposed to be charming Elizabeth, not telling her sob stories of his childhood. ‘Until then, we were living in Paris but it was a somewhat hand-to-mouth existence. Pretty ramshackle, in fact.’

That was better. Make light of the whole business. Because he had been happy at Saint-Cloud. Why wouldn’t he be? He’d been just a boy, oblivious to any undercurrents. His pretty mother’s favourite, an adored autumn child. Indulged by his genial father and fussed over by his older sisters even as they accused him of being spoilt. Nanny Roose had been the only sensible figure in the household.

‘Then … my mother became ill,’ he goes on. He doesn’t want to brush his mother under the carpet. Elizabeth must surely be aware of the times Princess Alice spent in sanatoriums, in any case. Still, he has the sense of stepping onto quaking ground.

His adoring mother, who had grown vaguer and more withdrawn, her eccentricities losing their charm as Philip was abandoned for spirituality and she declared herself a saint and a bride of Christ. There had been that miserable Christmas at Saint-Cloud when Alice took herself off to a hotel in Grasse, leaving his father, his sisters, and Philip to fend for themselves.

But it was fine, Philip reminds himself hastily. He was an energetic child, easily distracted. He had a bicycle he had saved up to buy for himself and there was plenty of fun to be had at school and mischief to be got into with his best friends the Koo brothers. He still winces at memories of steeplechases organised at the Chinese embassy where they lived, shouting and tussling between the precious china artefacts. No wonder Madame Koo had been glad to see the back of him when he went home!

‘Everything happened about the same time,’ he tells Elizabeth carefully. ‘My mother was unwell, my father went to live in the South of France, and my sisters all married. So that was the end of family life, I suppose. I just had to get on with it. You do. One does.’

One thing about Elizabeth, he realises, is that she is not going to gush or probe or be excessively sympathetic. Her restraint is obscurely restful, and in a perverse way only makes him want to tell her more about his unsettled childhood.

‘My parents wanted me to have a British education so I was sent to Cheam and my Mountbatten uncles stood as guardians while I was over here. Uncle Georgie – David’s father – was the one who came to sports days and prizegivings. He and Nada had a pretty colourful and tempestuous life together,’ he says, thinking wryly how that must be the understatement of the year. A Russian princess, Nada shrugged off scandal and her unconventional outlook is just one of the reasons Philip loves her.

‘They were wonderful to me,’ is all he tells Elizabeth, whose knowledge of sex is, he guesses, limited, to say the least. ‘I spent most of my half-terms with them, which is why David and I are so close.’

‘You still saw your family, though?’

‘Oh, yes. I’ve got relatives all over Europe, so we’d have big family meet ups with my sisters and my father, and various uncles and aunts and cousins. I never knew where I’d be spending the holidays. Someone would write and tell me to get myself to Wolfsgarten or Panker or Bucharest or wherever and I’d pack my trunk and catch a train.’

‘You must have been a very self-reliant child,’ Elizabeth comments.

He shrugs. ‘I thought it was normal, just like your childhood was normal for you. And those holidays were always fun, with everyone descending on a particular relative, and various cousins to play with. We had no shortage of places to stay and it’s not as if there wasn’t plenty of room. You know what those palaces and castles are like.’

‘No, I don’t.’ The sleet has eased at last and Elizabeth knuckles the wet from her cheeks. ‘I’ve never left the country. Balmoral is the furthest I’ve been.’

Philip is taken aback. He knew their experiences have been different, but not quite how different. ‘Oh … I suppose not,’ he says. He might envy Elizabeth her family, but how stultifyingly decorous and boring her childhood must have been, shuttling between Windsor, Buckingham Palace, Balmoral, and Sandringham, always surrounded by deferential courtiers.

‘So what are they like, these places?’ she asks.

‘Huge,’ says Philip briefly. ‘Most of them would make Buckingham Palace look cosy.’

‘Really?’ Elizabeth laughs in disbelief. ‘We always used to joke that you need a bicycle to get around BP.’

‘Wolfsgarten is the same. Some of the palaces are pretty dilapidated, too. I used to go and stay with my cousin Helen because Michael, her son, is more my age, and we had lots of good times there. He became King of Romania when he was five, though of course that didn’t mean much to us then. He was just a playmate. They had a crumbling palace near Bucharest but when it was very hot in the summer we used to like going up to Peles Castle at Sinaia in the Carpathian Mountains. It’s like something out of a fairy story, all turrets and towers and courtyards. Michael’s grandmother told the most marvellous stories in her bedroom. I always called her Aunt Missie, and if we were naughty, we weren’t allowed to go and say goodnight to her and hear a story. It was the worst punishment!’

He smiles at the memory and then breaks off, realising he has been running on. ‘Sorry. There’s nothing worse than someone rabbiting on about people and places you don’t know.’

‘I like hearing about your childhood,’ Elizabeth says. ‘It’s so different from mine. Go on. Where else did you go?’

‘Well, my sisters and I spent a few holidays near Le Touquet when I was younger with the Foufounis family. Like mine, they’re Greek émigrés and I was great friends with their children, Ria, Ianni and Hélène. They had a terrifying Scottish nanny they called Aunty.’ He smiles reminiscently. ‘Ianni and I used to get into all kinds of trouble.’

His memories of Berck Plage are muddled now, he finds. Dusty tracks. Sand between his toes. The weight of Madame Foufounis’s Persian rug on his shoulder when he and Ianni had the grand idea of pretending to be carpet salesmen like the Arabs on the beach. Poor Ria, up to her hips in plaster. The sinking feeling that followed the smash of a vase, knowing Aunty was rolling up her sleeves to deliver a sound spanking. Philip preferred his spankings from Nanny Roose, who was firm but fair.

‘And then there was Panker, the Hesses’s summer house on the Baltic Coast. There were always lots of us there too, a mass of children running around. We spent all day on the beach. I just remember miles of white sand and glittering water and a huge, windy sky and this marvellous light …’

He trails off. Without warning, his throat has snapped shut, clogged with a hard, complicated knot of memories.

Chapter 11

Elizabeth glances at him. For a time, he had been relaxed talking about his childhood, but clearly some memory has proved too much. A muscle is working in his clenched jaw. He looks furious and she suspects that it is with himself for sharing so much with her.

She is glad that he has. She wants to know more about him. She needs to know more if she is going to suggest marriage.

The thought makes Elizabeth’s heart thump once, painfully, against her ribs. She still isn’t sure that she dares, but seeing him again, talking to him properly, has changed things for her. Before, she can admit that she was infatuated with the idea of Philip. He was young, handsome, a hero. How could she not have been?

But now, now she has a better sense of him. She likes his quickness and his humour, likes his impatience with protocol. He is brusque at times, and arrogant, but he has a presence that Elizabeth feels she herself still lacks.

It is her duty to marry and to have a family. She wants that for herself, too, and why not Philip? He is a prince, after all, and he comes from a family used, like hers, to dynastic alliances. Mountbatten is keen on the idea, her parents less so, that is clear.

Elizabeth has the strong sense that if she wants him, she has to do something about it herself.

So she has decided to say something to Philip. She is desperately nervous about scaring him off altogether but she doesn’t need to make a big production out of it, she has reassured herself. It is not as if he can’t know that his uncle is pushing the idea of a marriage. Why else would he be here, after all?

But nothing has been said formally. Elizabeth is tired of being a dutiful girl, sitting at home in Windsor and waiting for something to happen. She wants to know what Philip thinks.

She is just going to mention the idea and see what he says.

Although … that is easier said than done.

Elizabeth opens her mouth to say that she’d like to talk to him about something, but immediately changes her mind. She cannot spring a discussion like that on Philip without warning.

‘You’re lucky to have such happy memories,’ she says instead, her voice trembling slightly with nerves. ‘But then, I don’t suppose it was all holidays and there must have been times when you would have liked a home of your own to go to.’

‘Sometimes,’ he admits with a grudging look. ‘But the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence, isn’t it? It’s an alluring idea, but where would that home have been and what would have happened to it by now? And in any case, I’m a restless fellow. I’m like a dog that longs for a basket of its own but can’t settle. There’s a part of me that finds the idea of being tied to one place and one person utterly appalling.’

There’s a tiny pause. For Elizabeth, it is a moment of complete clarity. Well, there is her question answered before she has asked it. Perhaps it was as well to wait.

‘I see,’ she says in what she hopes is an expressionless voice, but Philip stops and swears under his breath.

‘I’m sorry,’ he says, taking off his cap and dragging his hand through his hair. ‘I’ve a tendency to speak without thinking sometimes. It’s a bad habit of mine.’

‘What would you have said if you had been thinking?’

‘I don’t know … I hope I wouldn’t have made the idea of commitment sound so ghastly, for a start.’

‘Even if it is?’

‘It isn’t,’ he insists. ‘At least, not always. Of course I’d like to get married one day. It’s just … I’m not sure how good I would be at it. I haven’t seen many examples of a successful marriage – your parents excepted.’ He stares at Elizabeth. ‘How do you do that?’

‘Do what?’

‘Say almost nothing and yet make me be more honest with you than I am with almost anyone else.’

‘I’d like to think we can be honest with each other,’ Elizabeth says, choosing her words with care. ‘I know why you’re here. I’m sure you had more exciting and enjoyable offers of where to spend Christmas.’

She holds up a hand as Philip opens his mouth to deny it. ‘It’s all right. We have a very quiet life here. It’s how we like it. At least,’ she amends with a wry smile, ‘Mummy, Papa, and I do. Margaret would probably like more excitement.’

Calling the dogs, Elizabeth sets off once more. Now that they have started, she feels more composed and the conversation they need to have will likely be easier if they are walking. ‘I know Uncle Dickie thinks a match between us would be good thing … one day. You’re a prince, I’m a princess. We would both expect to marry … one day. Neither of us has a vast pool of potential partners to choose from.’ She is rather proud of her steady voice. ‘Things are different for us. We need to be pragmatic when it comes to marriage, so I perfectly understand why you’d want to come and … look me over, as it were.’

‘You make it sound as if I’m some horse trainer inspecting a prize filly!’

‘It comes down to the same thing, doesn’t it?’ Elizabeth’s cheeks are pink. ‘Breeding, bloodlines, finding the right match.’

‘You don’t think it’s about finding someone to love?’

The colour in her cheeks deepens at the thread of amusement in his voice.

‘I think my options, frankly, are limited. Yours are much wider. If you don’t want to, you needn’t marry at all. I, on the other hand, won’t have a choice in the matter. But I do want to get married,’ she adds honestly.

‘One day?’

‘Yes, one day.’

‘If you can find the right prince.’

‘Yes,’ she agrees on a breath.

Philip is silent for a while, clearly thinking. Their footsteps make no sound on the wet grass but Elizabeth can hear the dogs trotting busily around them, a whirr of wings as one of them flushes a pheasant from cover. The slow, steady drip of damp from the trees.

‘All right, I’ll be honest,’ he says eventually. ‘I don’t know what I want. Uncle Dickie does think I should try and sweep you off your feet, but you’re not someone who can be swept away, are you?’

How little he knows about her, Elizabeth thinks. He has occupied her thoughts for two whole years. She is grateful for the stolid expression that makes her hard to read. Some things – many things, in fact – she prefers to keep to herself. She is only young, but she has her pride and she has no intention of letting Philip know how desperately she wants him.

Because what he says is only partly true. She can’t be swept away by emotion, but only because she won’t let herself. The strength of her own feelings frightens her at times, so she keeps them firmly locked down. She doesn’t dare let them go, not when she has seen the effect her father’s sudden outbursts of temper have on people around him. Not when she knows how her Uncle David was punished for giving in to his emotions.

‘It’s too hard to plan anything while we’re still at war,’ Philip goes on. ‘I never know if a torpedo has got my name on it, and I want to live. If this damnable war has taught us anything, surely it’s that we should make the most of our opportunities. There’s so much I’d like to see and do, so much to be discovered; the thought of being tied down makes me itchy.’

Elizabeth keeps her hands in her pockets and her eyes down. They haven’t all learnt the same thing from the war. It has taught her not about opportunity but the price of duty. The responsibility of leading a country at war has weighed heavily on her father. She has seen the hollow exhaustion in his eyes, the care carved into his face.

A lifetime of duty is not much to look forward to, but she has seen the cost of shirking duty too. Her Uncle David chose love over duty and was exiled not just from his country but from his family too. Elizabeth will not risk the same fate. She does not dare. Better by far to keep her feelings under tight control.

‘But one day,’ Philip says hesitantly, ‘after the war … if you’re still looking for a prince …’

‘I could keep you in mind, perhaps?’ she offers when he leaves the sentence dangling.

He looks at her seriously. ‘I hope you will,’ he says. ‘I hope, if nothing else, we can be friends.’

Elizabeth’s face relaxes into a smile. ‘I hope so too.’

‘Will you keep writing to me?’

‘If you’d like me to.’

‘I would. Real letters,’ he says. ‘Not polite ones. Let me know what you’re thinking and feeling.’

‘If you’ll do the same.’

‘I will,’ says Philip. ‘I’ll be a better correspondent, I promise, and after the war …’

‘We’ll see,’ Elizabeth finishes for him, and he grins at her.

‘Yes, let’s see.’

Surreptitiously, Elizabeth lets a long breath leak out of her. In the end, the conversation has gone better than she has dared hope. Philip was never going to make a dramatic declaration of love. He is too honest for that, and no vows have been made, but they have made a proper connection. He has not ruled out a future together one day. And in the meantime, she has something to hope for and her pride is intact.

That evening is an enchanted one for Elizabeth. In contrast to the quiet Christmas gathering, the King and Queen have invited a number of guests for an informal party. Normally, her shyness makes such events an ordeal, but tonight Elizabeth is shining with happiness.

‘You look very pretty, Lilibet,’ her father says fondly, and Elizabeth realises with a start that for once she feels pretty. It is because Philip is there, because they are friends.

The King is not the only one who notices. ‘You’re the belle of the ball tonight,’ says Margaret, a little miffed as she is usually the one everyone looks at, the one who makes everyone smile. ‘Is that a new dress?’ she asks suspiciously.

‘Of course not. Honestly, Margaret, where would I get a new dress?’ Still, Elizabeth knows her eyes are sparkling, her cheeks becomingly flushed.

Even stern Tommy Lascelles unbends to compliment her on her looks, only to break off with a frown when he sees Philip and David moving furniture.

‘Your Royal Highness,’ he addresses Philip, tight-lipped. ‘Is there a problem?’

Philip glances up at him. ‘It’s time the party got going. We’re just rolling up the carpet so we can dance.’