Полная версия:

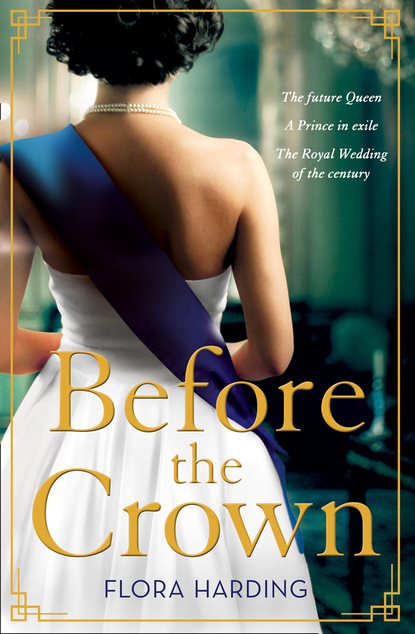

Before the Crown

Before the Crown

FLORA HARDING

One More Chapter

a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © Flora Harding 2020

Cover design by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

Flora Harding asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This is a work of fiction. Every reasonable attempt to verify the facts against available documentation has been made.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook ISBN: 9780008387532

UK B Format Paperback ISBN: 9780008387549

Canada Trade Paperback ISBN: 9780008411701

UK Audiobook ISBN: 9780008406448

US Audiobook ISBN: 9780008412074

Version: 2020-06-15

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1: Windsor Castle, December 1943

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12: Cairo, April 1944

Chapter 13

Chapter 14: London, 8 May 1945

Chapter 15

Chapter 16: Buckingham Palace, January 1946

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21: Germany, Schloss Salem, April 1946

Chapter 22

Chapter 23: Café de Paris, Monte Carlo, April 1946

Chapter 24: Buckingham Palace, May 1946

Chapter 25: Balmoral Castle, August 1946

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29: London, October 1946

Chapter 30: Portsmouth, 1 February 1947

Chapter 31: South Africa, February 1947

Chapter 32

Chapter 33: London, May 1947

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37: London, June 1947

Chapter 38

Chapter 39: London, July 1947

Chapter 40: Buckingham Palace, July 1947

Chapter 41: London, July 1947

Chapter 42: Balmoral Castle, August 1947

Chapter 43: London, October 1947

Chapter 44

Chapter 45: Buckingham Palace, November 1947

Chapter 46

Chapter 47: London, November 1947

Chapter 48: Buckingham Palace, November 1947

Chapter 49: Buckingham Palace, November 1947

Chapter 50: Kensington Palace, 20th November 1947

Chapter 51: Buckingham Palace, 20th November 1947

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

Windsor Castle, December 1943

He’s not there.

Elizabeth has her eye pressed to the chink in the curtains. The velvet is worn and smells musty. It reeks of mothballs and greasepaint, of old productions carefully rehearsed, suppressed giggles, and first night nerves.

In front of the stage, she can see the audience beginning to fill up the rows of chairs. Some are taking their seats in deferential silence, others look around, defiantly casual about finding themselves in the castle. The splendid gilt of the Waterloo Chamber is dulled now by neglect, its walls stripped of famous portraits, but it retains plenty of its original grandeur. The carpets had been rolled up and stored at the beginning of the war, and now the great hall echoes with the scraping of chairs, the subdued burble of conversation, and the clearing of throats.

The front row is empty still.

‘Is he here?’ Margaret whispers, crowding at her shoulder.

‘Not yet.’ Elizabeth steps back from the curtains, disappointment a leaden weight in her stomach which is already rolling queasily with anticipation and stage fright. This will be the fifth performance of Aladdin, and though she knows all her lines, still there is that moment when the curtains are hauled back and the terror of failure clutches at her throat.

‘Let me see.’ Margaret elbows her sister aside and takes her place at the curtain as if she can conjure Prince Philip of Greece into space by the sheer force of her will.

Sometimes Margaret’s will is so strong, Elizabeth almost believes she could succeed but on this occasion her sister’s drooping shoulders indicate failure. She lets the curtains drop back into place and turns back to the stage, kicking at her satin skirts.

‘Papa said Philip would come,’ she pouts.

‘For Christmas,’ Elizabeth reminds her, trying to disguise the dullness in her voice. ‘He didn’t promise to come for the pantomime. Something may have come up.’

Margaret stares. ‘Something more important than joining the King and Queen to watch their two daughters perform?’

‘Philip’s a prince. He’s not going to be impressed by a couple of princesses.’ It is Elizabeth’s secret worry. She has spent her whole life being special, and now, the one time it matters, she may not be – at least, not for Philip.

It’s been two years since Philip of Greece took tea with the King and Queen. Elizabeth and Margaret sat enthralled as he entertained them with his wartime experiences at sea, deliberately making light of his own part and playing up the funny side of things. For Elizabeth, whose only memory of Philip up to that point had been of a bumptious cadet who had showed off terribly, it had been a revelation. The swaggering boy had been replaced by a young man who was everything a prince should be: brave, witty, charming.

And handsome. The memory of those penetrating blue eyes has been a tiny, insistent throb inside her ever since.

Not long afterwards, the royal family were invited to a party at Coppins, where Philip was staying with his cousin, Marina, Duchess of Kent. Philip asked Elizabeth to dance, either out of kindness or out of duty. She knew that much. She was fifteen and tongue-tied, burningly aware of his hand at her waist, his palm pressed against hers.

She is seventeen now. She longs for him to see that she has grown up.

‘He ought to want to come and see us,’ says Margaret stubbornly. She’s been looking forward to impressing him with her acting skills. ‘Especially you,’ she adds, uncharacteristically ceding centre stage to Elizabeth. ‘He’s been writing to you.’

‘Sometimes.’ Ever cautious, Elizabeth won’t even admit to her sister how she has pounced on Philip’s rare letters, how many times she has read and reread them, smoothing out the creases in the paper. They have told her nothing because what could they say? That he has remembered her, that’s all. But it has been enough. ‘He probably writes to lots of people.’

‘Lilibet, you’re going to be Queen of England one day. You are not “lots of people”.’ Exasperated, Margaret stalks across the stage, her heels clacking on the wooden boards.

‘Margaret!’ There is a hiss from the back of the stage where Crawfie, their governess, is beckoning. ‘You too, Lilibet. The King and Queen are just coming in now. You need to take your places for the show.’

Elizabeth draws a breath. It doesn’t matter that Philip isn’t here. She will not be disappointed. He is coming for Christmas. She will see him soon.

Beyond the curtains she can hear the rumble and scrape of chairs being pushed back as the audience stands for her parents.

‘Quick, into the basket!’ Cyril Woods scampers across the stage. Elizabeth likes him. He is jaunty and bright-eyed, and he dances and sings nearly as well as Margaret. The two of them carry her scenes, Elizabeth knows. She learns her lines and moves when she is supposed to, but she doesn’t have Margaret’s dazzle. Next to her sister, she is muted, dull. That is how she feels, anyway.

But she is the elder; she will be Queen. So she has the starring role. It is Elizabeth who is playing Aladdin, in a shockingly short jacket and tights that make her feel very exposed. Margaret is Princess Roxana, which she doesn’t mind as she gets to wear a gorgeously embroidered silk robe and a tiara.

For the opening scene, they are to jump out of a huge laundry basket. The back has been cut out so they can crouch behind it. There isn’t much room and Cyril keeps touching her leg by accident. ‘Sorry,’ he mutters. ‘Sorry.’

Elizabeth’s heart is thudding. Oh, how she hates this moment before the curtain goes up! Her mind has gone blank. Her costume is too tight and she can’t remember a single line. The wicker basket is tickling her cheek and her legs are already stiffening. As the Guards’ orchestra strikes up the fanfare, she is gripped by the longing to leap up and bolt from the stage, to run out into the Upper Ward and down to the stables. To ride far, ride fast, to a place where there is no one to fail and no one to please and no duty to be done.

But she cannot do that. The show is one of the few contributions she can make to the war effort. Proceeds will go to the Royal Household Knitting Wool Fund to provide comforts for the troops who are fighting for their country, Elizabeth reminds herself sternly. They aren’t allowed to run away. All that is being asked of her is to sing and dance. What kind of example would she set if she were to refuse even that?

It is too late now in any case. The orchestra is reaching a crescendo, the drums are rolling and there is a swishing of velvet and a creaking of ropes as the curtains are hauled back.

‘You’re on!’ Cyril jabs Elizabeth in the side and she springs up, tossing the lid of the basket aside. Her sudden appearance provokes laughter, which increases as Margaret pops up beside her, but Elizabeth doesn’t even notice.

Philip is in the front row, sitting next to her mother, and he is looking right at her. His expression is astounded and a smile is just starting to curve his cool mouth.

Elizabeth’s heart swells. Her doubts are forgotten. All at once she can sparkle like Margaret. Her feet are lighter, her smile brighter. She can dance, she can sing. She can arch a brow and cast a knowing look at the audience.

She can make Philip laugh.

He is there. That is all that matters.

Chapter 2

Next to the Queen, Philip is trying not to make it obvious that he is nursing the hangover from hell. Why in God’s name did he drink so much last night? But it was his last chance to see Osla before Christmas.

It was fun, at least what Philip remembered of it. They danced at The 400 and then somehow a party congregated in Osla’s flat where they ate the Russian salad she made with powdered egg. Last night it hadn’t seemed disgusting, but the liquid paraffin dressing is still roiling in his stomach. He slept on the sofa and he should have stayed there instead of making the fatal error of returning to the flat in Chester Street where he found a letter from Mountbatten urging him to present himself at Windsor Castle as soon as possible.

Letters from Uncle Dickie are hard to ignore.

‘Your grandfather was a king,’ Mountbatten said the last time Philip had seen him. ‘You’re a prince, connected to most of the royal houses of Europe. But what have you got to call your own? Barely more than the clothes you stand up in.’

‘And that sweetheart of a car you gave me for my twenty-first birthday.’ Philip loves his MG.

Mountbatten was not to be diverted. ‘You know what I mean, Philip. You’re a personable fellow, and Lilibet will be Queen one day. Make yourself agreeable to her, as I hear you’re more than capable of doing. Dammit, you owe it to your family and to yourself. The war won’t last forever, and then what will you do? You’re not a British citizen and you won’t be able to stay in the Navy.’

Philip can’t imagine the war being over. It seems to have been going on forever. If Philip is as honest with himself as he tries to be, he has been enjoying the war.

There are flashes of terror, of course, but more of adrenalin and anticipation. In unguarded moments, the screams of injured men echo, and memories of flames and thrashing limbs and the vicious rat-tat-tatting of machine guns surge and spin in his head, leaving him stranded on the edge of an abyss, temporarily unable to catch his breath, but when that happens he simply pushes them away. It is war, that is all, and he hasn’t suffered so much as a scratch.

Philip prefers to think of the pitch of the ship and the dazzling Mediterranean light. The sense of liberation as they ease away from the quay. The stomach-clenching excitement when the order for battle stations crackles out of the speakers.

It is harder here, he thinks. The country is exhausted, its cities bombed, its people grey-faced and worn down by rationing and blackouts. In London, Philip walks past ruined buildings without noticing them anymore. Once, he was with a party heading for the Café Royal only to discover that it had been bombed barely minutes before. Dust still hung in the air. There were bodies lying on the pavement, men in evening dress, women in furs and diamonds that glittered in the moonlight. The looters were already there, stripping away jewels from the dead and dying, pulling up satin dresses to rip off nylon stockings.

Philip remembers stepping past and going on to The 400 instead.

That’s how it is during a war. Nobody knows when the next bomb will drop, when the torpedo will hit, when that Messerschmitt will slide out from behind a cloud and shoot you down. There’s a febrile edge to socialising. The knowledge that each night might be the last time you dance, or laugh over cocktails, or kiss a girl, makes it hard to be sensible and go home early to bed. So they stay up, determinedly dancing and drinking and laughing, squeezing every last drop of enjoyment out of an evening.

It is a world away from Windsor Castle. Here, in the Waterloo Chamber, there is little sign of the chaos and destruction elsewhere. The famous Lawrence portraits have been taken down and in their place – Philip squints to make sure he hasn’t imagined this – are bizarre cartoon characters. But otherwise little seems to have changed since the previous century. The King even leant across the Queen to tell Philip that the stage and curtains are the very same ones used by Queen Victoria’s children for their theatricals.

Philip’s head is aching, a ferocious grinding that jabs every time anyone shifts in a chair, sending it scraping across the floor. He feels fuzzy and stale. Perhaps he really is coming down with the flu that was his excuse for not arriving until last night?

‘Go and help with the pantomime,’ Mountbatten urged.

‘I’m not prancing around on stage making a fool of myself in front of the King!’

‘Make yourself useful backstage, then. There must be something you could do. It’d go down very well. The King and Queen like that kind of thing.’

The more Mountbatten pushes, the more Philip digs in his heels. He’s like a dog being dragged to a bath.

‘Philip, you’re halfway there.’ Uncle Dickie can’t understand why Philip is so reluctant to press his case. ‘The King said Lilibet was very taken with you when you saw them in ’41. She’s been writing to you, hasn’t she?’

‘Occasionally.’ Philip knows he’s being contrary but he can’t help himself. Elizabeth’s letters have been more than occasional. Written seriously in a childish hand, he has found them obscurely touching, though he will never admit as much to his ambitious uncle. He is deliberately keeping things light. He is grateful that she hasn’t embarrassed him by asking for his photograph, and he has been careful never to suggest that he would welcome one from her. That would be taking things a step too far. ‘She’s just a young girl, Uncle Dickie. She hasn’t got much to say.’

Mountbatten waved that away. ‘I hope you’re writing back?’

‘When I can. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but there’s a war on.’

‘You seem to have time to go drinking and dancing on shore leave,’ his uncle had pointed out.

‘I do write.’ Not that he had much to say either.

The truth is that he has struggled to remember much about Elizabeth. A quiet girl, sturdy and sensible, she has always been there at various family events like his cousin Marina’s wedding to the Duke of Kent and naturally she had been at her father’s coronation, which Philip remembered clearly. They had played croquet together at the Naval College in 1939 when Uncle Dickie, that old intriguer, had somehow arranged for Philip to look after the two princesses while the King and Queen attended chapel. There had been mumps, or measles, or some medical reason why Elizabeth and Margaret hadn’t gone too.

Philip wouldn’t be surprised if Mountbatten had engineered the whole outbreak just to put his nephew in front of the King’s oldest daughter. Not that Philip thought it had done much good. Elizabeth was painfully shy, he seems to remember, and rather chunky. He had hardly been able to get a word out of her. There had been a good tea on the royal yacht, though. He remembers that.

Good Lord, his head hurts. If only he’d been able to find an aspirin but it wasn’t the kind of thing you asked for the moment you were ushered into the Crimson Drawing Room where the King and Queen were greeting their guests for the pantomime.

The last thing Philip wants to do right now is to sit through a pantomime. The Waterloo Chamber is so big it must be impossible to heat at the best of times but with the royal family anxious to share in the country’s wartime privations there isn’t so much as an electric bar to warm the air and the cold is penetrating. He envies the Queen her fur coat.

In spite of the cold, he’s very tired. Osla’s sofa isn’t the most comfortable of beds. The effort of suppressing a yawn leaves the muscles in his cheek aching. Surreptitiously he pinches the bridge of his nose between his thumb and forefinger. The last thing he can afford to do is nod off. For all his recalcitrance, he knows Mountbatten is right and he needs to make a good impression on the King.

‘And the Queen,’ his uncle warned. ‘You’ll have to work harder with her. It’s not at all helpful of your grandmother and great aunts to keep referring to her as a common Scottish girl!’

So far the Queen has been charm itself, but Philip is aware that her sweet smile is at variance with her sharp blue eyes.

At last, the main lights go out and the orchestra gets going. There’s some rousing music and just as Philip is seizing the opportunity to slide down in his seat, the curtains are dragged open. The drum roll bangs a conclusion, the lid of the laundry basket on stage is tossed aside and up pops none other than Princess Elizabeth, heiress presumptive to the English throne.

There’s a tiny moment of silence when she seems to be looking straight at him, and he’s so taken aback that at first he can only stare back, his headache forgotten, before he starts to grin at the sheer absurdity of it.

Then she smiles – another shock, as he doesn’t remember her smiling like that – and starts to sing as she comes out from behind the basket. She is wearing a red and gold Chinese jacket and filling it out very nicely indeed. The jacket reaches her thighs. Beneath it, she is wearing only a pair of satin shorts and silk stockings that reveal surprisingly shapely legs.

Philip whistles to himself and sits a little straighter.

He watches with new interest as Elizabeth tap dances across the stage. The show is better than he had expected, he has to admit, and he even finds himself laughing out loud at the more groan-worthy jokes. Princess Margaret is very pretty and undoubtedly the better performer. She has a better voice and is a better actor, but Philip’s eyes keep going back to Elizabeth. She is positively sparkling.

She must be seventeen by now, he calculates. He hasn’t realised what a difference two years can make. Uncle Dickie’s exhortations to fix his interest with her suddenly don’t seem quite as tiresome.

Chapter 3

Elizabeth feels as if she is smiling with every cell in her body as she joins hands with Margaret and the rest of the cast and bows. The curtains fall into place with a dull swish. Never has she danced so well, sung so well. Dressed as a washerwoman in a sackcloth dress and an apron, she sang ‘We’re Three Daily ’Elps’ with Margaret and Cyril and thrilled at the sight of Philip throwing his head back and laughing. No tight smiles or simpers for Philip of Greece.

She is trembling with excitement and anticipation as they leave the stage, but when Philip comes backstage to congratulate her, her confidence evaporates abruptly. After dreaming of him for so long, the reality of him is intimidating. He is taller than she remembers, the lines of his face harder, the icy eyes bluer. He seems to take up more than his fair share of air so that her breath shortens and she feels twitchy and exposed.

He comes in with the King and Queen and his intimidatingly elegant cousin, Marina, Duchess of Kent with her languid, tilted smile and exotic accent. Elizabeth remembers being a bridesmaid at Marina’s wedding to her uncle George. Philip was there, too, but he was just a boy then, an alien creature Elizabeth watched out of the corner of her eye. Uncle George was killed on active service last year, and Marina is facing her widowhood with courage. She is effortlessly beautiful and has a warmth, a kindness and an easy charm that Elizabeth admires and envies.

‘What fun that was!’ Marina kisses Elizabeth warmly. ‘You were marvellous, darling.’

Elizabeth smiles and thanks her, and kisses her parents, but all the time she can feel her gaze being dragged to Philip, who is standing a little behind them. She doesn’t want to look at him, she is determined not to, in fact, but it is as if her eyes are iron filings being sucked remorselessly towards a magnet. When the others move on, he lingers, and she doesn’t know whether to be delighted or terrified.

‘I say, that was terrific,’ he says warmly. ‘Very funny indeed.’

‘Thank you.’ The old terrible shyness clamps around her throat. She is still wearing the costume with the jacket and tights and she turns the saucy cap she has worn on stage between her hands, keeping her eyes firmly fixed on it. ‘Mr Tannar, the headmaster of the Royal School, wrote the script, so it’s nothing to do with me really.’

‘I don’t agree. A script isn’t any good without good actors. I enjoyed it. The laundry scene was very funny. Especially with the iron burning through all those “unmentionables”.’