Полная версия:

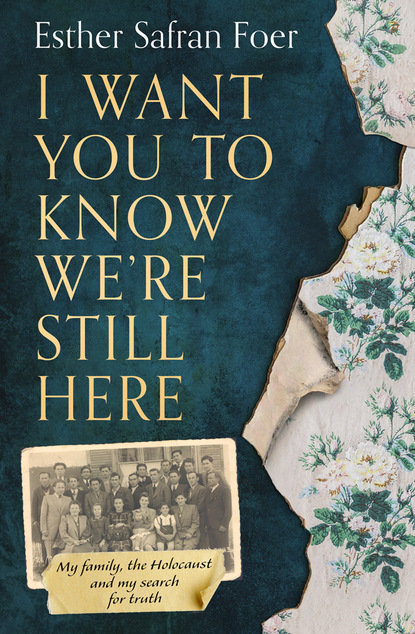

I Want You to Know We’re Still Here

“Memory begat memory begat memory,” Jonathan writes of his fictitious “Trachimbrod,” and it is in fact in these memories that my knowledge of the real Trochenbrod resides. Over the years, this search has led me to voraciously absorb every detail and anecdote that I can find, to assemble information about Trochenbrod piecemeal, like the shards of memory in my glass jars:

We know that after the rain fell, the air smelled like wildflowers.

That there was mud.

And geese.

And snakes.

And these snakes, according to one survivor, were so plentiful that they would come into the houses and the children would play with them and feed them at mealtimes, like pets. Once, a rabbi came to Trochenbrod and, hearing the complaints, said, “I will drive them away!” The rabbi went out into the field, tore up some grass, and threw it into the next field while uttering some words—a prayer, or a spell, or a shopping list, or a curse. Whatever it was, it worked, and that was the end of the snake infestation in Trochenbrod. Or so the story goes.

We know, from the interviews and memoirs of survivors, there were good solid houses, on high foundations, rectangular, with dirt floors.

A prosperous town, the population was 99 percent Jewish.

A thriving commercial center, it was the place to shop.

Some believe Sholem Aleichem visited Trochenbrod and drew inspiration there for his character Tevye the Dairyman.

The smell of freshly baked bread infused the air as the Sabbath approached, and in the summer, with the windows open, it might have been possible to hear everyone in town singing the same songs on the Sabbath, as though the village was one big family at one great meal.

The shtetl is gone and yet it still shapes my life. I have spent what seems like a lifetime gathering testimony from books and documentaries, from the few family photos that remain, from survivors’ accounts, from oral histories, from reunions of survivors, and from the visit to Trochenbrod that I would undertake in 2009, with my son Frank. My home office overflows with papers and photographs, with large three-ring binders labeled “Trochenbrod,” with boxes and folders full of documents and family stories. With map reproductions—some of such ancient provenance they look like they ought to be peopled by dragons and mythical beasts. With letters—tucked inside a folder, one of them five pages long, in neat, handwritten Yiddish from Itzhak Kimelblat in Brazil, eager to tell me his story, to maintain a connection to this vanished place.

While much of what I know about my family history has been deliberately and painstakingly assembled, a lifelong research project that has sent me on a scavenger hunt through libraries, the Internet, and around the globe, the broad outline of Trochenbrod’s history requires no excavation—the arc of its inception to its violent decimation is readily accessible from the history books.

Trochenbrod was part of the Second Polish Republic before it was part of the Soviet Union before it was occupied by Nazi Germany as part of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact—or the German–Soviet Non-Aggression Pact or the Nazi German–Soviet Treaty of Non-Aggression, depending on which Wikipedia entry you prefer or where you stood in relation to the tanks.

Without getting too deep into the weeds of history, it is worth considering how it is that Jews wound up cultivating this marshy parcel of land, with its remote location, its poor soil, and its many snakes. Avrom Bendavid-Val, who was driven by a similar compulsion to explore Trochenbrod, notes in his book The Heavens Are Empty that Jews were not historically known as farmers, perhaps because of the conflict between religious practices and the demands of agrarian life—or maybe simply because of prohibitions against Jews owning land.

The short answer is that this part of Ukraine wound up, in the late 1700s, in what was known as Russia’s Pale of Settlement, which stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea and was home to between five and six million Jews.

It was in many ways idyllic and in more ways not. Jews were subject to heavy taxation, conscription into the Russian army, and were denied many civil rights. But they could avoid some of the more draconian measures if they agreed to cultivate farmland, which is what resulted in the creation of the Jewish shtetl of Trochenbrod.

These things I know from history books. What I have been able to gather from piecing together family history is more prosaic:

I know that my father’s mother, Brucha, and her family lived in Trochenbrod, one house away from where her brother Yurchem and sister-in-law Sosel lived.

That a few houses farther up, on the same side of the road, were cousins Avrom and Sara Bisker.

That next door to them was Peretz Bisker, father of Ida Bisker Kogod, grandfather of Bob Kogod, whom we met in the United States. On the other side of the street were the Kimelblats, whose son Shai married my father’s half sister, Choma.

I know that in Trochenbrod everyone had a nickname, something I learned later was important in identifying people. I would also learn that nicknames were derived from either a shortcoming or a profession. Accordingly, there was Chaim Nutta, the shoemaker. And Shaul Avramchick, who was known as the big eater; “Belly Button” Itzy, who was a government-appointed rabbi. There was Leib “the big one” and Leib “the small one.” There was Itzy “with the nose” and Helchick the butcher and Ephraim “who cries in the synagogue” and Pinchas the carpenter and Yankel the blacksmith and Chava the midwife and Ydel “the dumb one,” and I could go on and on, and perhaps I should, because part of the point of this narrative is to keep these stories alive.

Despite my efforts, it remains the case that I know virtually nothing about the Safran side, my paternal grandfather’s family. I don’t know whether my grandfather had any siblings or where he came from. I hired a researcher in Ukraine in 2005 to try to find documents that might shed light on my grandfather’s family. He found nothing and believes my grandfather Yosef Safran came from elsewhere, probably a larger town. The only record that I could find is a 1929 Polish business directory available on the Internet, which lists a “Szafran” doing business in Trochenbrod.

Actually, I learned years later that my grandmother’s family, the Biskers, didn’t exactly come from Trochenbrod but from its adjacent sister village, called Lozisht. The two were connected, along a single road, and always thought of together.

While my father had some distant cousins in the United States, none of them knew him before he immigrated. His closest relatives were three first cousins living in Israel. From them I learned that my grandmother Brucha remarried and my father had a half sister, Choma or Nechoma. My father’s cousin Shmuel Bisker told me that my father was not only his cousin but his best friend.

I know that, according to Shmuel, my father was the best student for miles around and that he always had “a head for business.”

I know, from my mother, that my father was always running: building a business, going from one store to the next. In the end, maybe there was finally no more running left in him.

I know, from reflection, that outlasting the war didn’t necessarily mean surviving.

There is only one picture of my father taken before my parents met: It’s the black-and-white photo of him, another man, and two women. My mother told me that she met the other man in the photograph twice, when he came to see my father in Lutsk. She remembers my father taking great care of the man, and she thinks the man was always smiling—in her mind this was because he was proud that he had helped to save my father. She said the man came to Lutsk because he wanted my father to return to their village to live and to marry his daughter.

When I asked my mother why she didn’t know more or ask questions, she said that after the war people didn’t want to talk about the past. This must have been especially true when survivors, like my father, remarried and started new families. They wanted to move on and focus on building new lives. Then, when they came to the United States, no one asked questions. American relatives were either afraid to ask or afraid to hear what had happened in Europe. Maybe they didn’t know how to ask. Or maybe they felt guilty for not having done more to help their families.

And yet, after the passage of all this time, there is a need to remember, to take whatever fragments I can find and piece together a vanished shtetl where the living quarters and the stables for the horses and cattle were sometimes one and the same, and where the chickens were kept behind the stove, and the potatoes under the bed, and in the winter, during the heavy freeze, the calves were kept inside the house. Where there were not only snakes but a flame. And every evening the flame could be seen glowing near the forest. Sometimes the flame would be large and sometimes small. Sometimes it would appear low down near the ground, and at other times it would leap high. As with the snakes, the people in Trochenbrod grew accustomed to it. When a person went up close to take a look at the flame, it disappeared. Whether or not there really was such a flame, or the snakes were pets, or Trochenbrod was an inspiration for Sholem Aleichem, this vanished shtetl was so colorful, so magically rendered by its former inhabitants, that it’s no wonder my son Jonathan turned it into a work of fiction.

We know there was a strong work ethic and fertile soil in Trochenbrod.

There were dairy farms, leather factories, a glass factory, retail shops, school buildings, synagogues.

The children who grew up in Trochenbrod were strong and healthy—a “Trochenbrod boy,” it was said, “could knock out ten peasants!”

There was only one Christian family—under Polish law, the postmaster could not be Jewish.

Jewish families from neighboring villages sent their girls to Trochenbrod for fattening before marriage.

The entire town came out to celebrate weddings.

Gentile women came from nearby villages to milk the cows on the Sabbath.

The town had one main, unpaved road, running through Trochenbrod and up through Lozisht. It was lined by bollards meant to prevent the horses from slipping into the drainage ditches alongside the thoroughfare.

Menorahs for Chanukah were crafted from halved potatoes (the ones, perhaps, that were kept under the bed) into which a small hole would be made, and oil poured, and a piece of cotton lit.

Behind each house was farmland, behind which was forest.

There was no electricity.

Mud bears repeating twice.

When the Germans arrived in 1941, the Trochenbroders did not, at first, panic. They had lived under German rule before, and in fact many remembered that, during World War I, the Germans served as quasi-protectors from the Russians.

We know that even if the people of Trochenbrod did sense that something was about to happen, the way that my mother knew, a certain stasis may have set in. It is easy, with hindsight, to sense that one should flee, but when I try to imagine myself in that situation, I understand how hard it would be to leave behind everything I had ever known. To simply walk away from your life, your friends, your home, your few possessions. Besides, there was the possibility that some of the stories circulating at the time, about what had happened to others, were perhaps not true. Or maybe they were true, but whatever had happened to them couldn’t possibly happen again.

This is why the people of Trochenbrod were later referred to as luftmenschen, which translates to “airmen” or to “one who is not a realist,” because they did not believe the truth.

Some of the Jews were employed by the Germans to police their own, and they were called Judenrat.

The Ukrainians from neighboring villages were encouraged to rampage.

On August 9, 1942, twenty men from a German extermination unit arrived: Einsatzgruppe C.

There were eleven army trucks.

The Jews were ordered to the center of town. This included Trochenbroders and Jews from eastern Poland who were escaping the Nazis.

They were told to line up and to put a hand on the shoulder of the person in front of them.

The Germans took pictures and measured the length and width of these people standing in line, the Jewish population, so that they could then use those measurements to calculate the depth and width of the necessary graves.

But the calculations would not be entirely accurate, because some of these Jews were shot, randomly, along the way.

They were told they would now relocate to a ghetto.

On August 11, people were taken two hundred at a time to the pit and shot in what is known as the first “Aktion.”

Five hundred to one thousand people remained alive.

Some of them fled into the forest. But then, on Yom Kippur, September 21, many of them emerged from the woods, hungry and frozen, to celebrate Yom Kippur together, and the Germans were waiting.

By the time this was over, roughly sixty Jews were left.

Germans worked the land for a while, after the Jews were gone, until the Jewish partisans, who were resistance fighters, came back and destroyed some of the village.

We know from Israelis born in Trochenbrod that, after that, the Soviets destroyed the rest of what remained. The Soviets wanted to erase physical evidence of a Jewish settlement, so they carried off any remnants and incorporated the land into a kolkhoz, a Soviet collective farm, ironically named “New Life.”

What I know about how my father managed to escape the massacre of his ghetto is largely because of his cousin. Ida Bisker Kogod, meeting my father for the first time in the United States, dared to ask him how he survived. He told her that he and a friend, another Jew in their ghetto, were sent by the Nazis on a work detail to repair windows in a train station some distance away. It was during that time that the Nazis decided to liquidate the ghetto in Chetvertnia, where he and his family had been taken. When my father and his friend returned, a Ukrainian with a horse and wagon told him that everyone had been massacred. According to my mother, my father said that his first instinct was to turn himself in and die with the rest of his family. The Ukrainian, as the story goes, told him he could do that later, but meanwhile he hid him in his wagon and covered him with straw. He allowed my father to stay with him for only one night, afraid that if my father was found in his house, the Ukrainian farmer and his family would be murdered.

I don’t know where my father was during most of the war. One former Trochenbroder told me that he is sure he went east, all the way to Moscow. I can’t imagine how that is possible and I will probably never know. What I do know is that at least at the end of the war he was hiding in the home of a neighbor, the one in the picture that my mother managed to save. He survived because one righteous person risked his life and those of his wife and children by letting my father hide in the barn behind his house. I don’t know for how long or when during the time of the German occupation he hid there. The man’s children stood guard outside, taking turns pretending to play as a way to keep watch for any approaching Germans. Fortunately, after the exterminations, the Germans entered the village only intermittently.

The picture has some scribbling on the back. Over the years, we tried to make sense of it but couldn’t. The one word that we could make out was something like “Augustine,” which we thought might be part of an address. Maybe it was a town. Or a street. Or a person.

This was the photograph that Jonathan took with him, years later, as he left for the trip to Trochenbrod that gave rise to Everything Is Illuminated. He had set out to find Augustine.

4

In the wedding photograph, such as it is, my father wears an elegant dark suit and a crisp white shirt. His tie is striped, and what appears to be a new fedora sits atop his head. The camera has caught him with his eyes half open, which is halfway more than my mother’s, closed beneath the white veil that obscures her face.

Were they thinking about the past with those hooded eyes or conjuring some better future? Who can say? What is evident from this photo, however, is my mother’s trademark superstition. Something, or someone, has been disappeared—literally cut out of the picture. It’s no neat job, this erasure. Unlike the discreet photoshopped removals of today, this one more closely resembles a decapitation. When I asked my mother who this was, she explained that two weddings took place that day, one right after the other, which was bad luck. Presumably she meant the other couple had been excised from this photograph, but it’s really hard to tell, because there are two other random people visible here, as well as a pair of hands.

I have one other picture that looks like it was taken either right before or right after the wedding. My father is in the same suit and tie. My mother and father look so happy, close to each other, with their heads pressed together. My mother, with her hair pulled back, is wearing a beautiful dress with a large brooch. It is my favorite picture of my parents, and this is how I like to think of them, looking radiant, even if their happiness was brief.

My parents on their wedding day.

At least I have these mementos, along with the tattered ketubah, a Jewish wedding contract, mended over the years with now-yellowing tape. This I found tucked inside my mother’s sturdy secret cardboard box, carefully covered with decorative Con-Tact paper and always hidden in the back of a closet until I was able to retrieve it many years later. Part of the ketubah is missing, torn neatly along the seam, but unlike the deliberate doctoring of the photograph, this missing part appears to be unintended, just an unfortunate consequence of age. The ketubah is quite large and decorative, preprinted with blanks to fill in.

My parents married in Lodz, about seventy-five miles southwest of Warsaw, on May 5, 1945, according to DP-camp documents that I found. They had known each other only a few months, after meeting in Lutsk, in western Ukraine—the largest city in the vicinity of their respective shtetls and a gathering place for Jewish survivors. By the standards of the time, they were practically an old couple. Quick marriages were typical among refugees. Some couples married after meeting only weeks before, according to my mother. “Life wasn’t normal,” she explained. There was no time to worry about normal, whatever that meant or had once meant. These were people who had lost everything and everyone—entirely, tragically, literally. They were eager to begin life again, to start families, or new families. To close their eyes and commit to life.

I was talking with a friend whose parents were also married in Poland at around the same time. When I told him that my parents were married on May 5, he looked right at me and said, “No, they weren’t.” How did he know? He said his parents were married in another Polish city on May 1 and that I needed to check the ketubah carefully. He was right. May 5 was a Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, a time when weddings are not performed, except after sundown. The ketubah has the Hebrew date of the eighteenth day of the month of Iyar, which is the Jewish holiday of Lag B’Omer, the same holiday on which my mother says she was born. Omer is a forty-nine-day somber period between the festivals of Passover and Shavuot; the origins of the holiday are unclear. But we do know that the thirty-third day of this period, Lag B’Omer, offers a break from the mourning and is the one day during this period when Jewish weddings are permitted.

Jews desperate to start new lives, whatever they may have believed after what they had been through, were waiting for the thirty-third day, for an official Jewish wedding. It is the day my parents got married and the day my friend’s parents got married along with many other Jewish refugee couples. In 1945 Lag B’Omer was on May 1. Interestingly, this was the day after Hitler committed suicide. Just a few days later, on May 7, the Germans surrendered, ending the war in Europe.

Lodz, where my parents married and where I was born, was the second-largest Jewish community in prewar Poland, after Warsaw. Warsaw was totally destroyed in the war. Lodz, however, survived German occupation with relatively little physical damage. One-third of Lodz’s population had been Jewish prior to the war. Of the approximately 233,000 Jews in Lodz at that time, about 200,000 were forced to live in the city’s ghetto, and it is estimated that somewhere between only 5,000 and 7,000 Jews from the ghetto survived. By 1946 the number had swelled to about 50,000 Jews, most from elsewhere in Europe, who saw it as a waystation and crossroads from the east as they tried to escape a Europe that clearly did not want them.

My parents lived in an apartment in Lodz that had once been occupied by a murdered Jewish family; the city was full of empty homes and businesses that had previously belonged to Jews.

They shared their first apartment with another Jewish refugee couple, who were also expecting a baby. Whoever managed the doling out of these vacant apartments must have figured this was a good match: Both women were expecting their first child, without any family members to help, so they would presumably benefit from mutual support.

The couples agreed that the first mother to give birth would get the best bedroom and the other mother would help take care of the new family and cook for them. Then they would change places when the next baby was born.

There is no official record that I have been able to find of my arrival in a Lodz hospital on March 17, 1946. I slid into the world right under the iron curtain. Days before I was born, on March 5, 1946, Winston Churchill gave one of his most famous speeches, at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, announcing “… an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe … and all are subject, in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and in some cases increasing measure of control from Moscow.”

A researcher that I hired to find my birth certificate was unable to locate any documents. Apparently, at that time in Poland, births were not automatically recorded. My parents would have had to make an effort to register the birth, and it’s possible that they had seen enough to know that being on any official registry at this moment in history would be unlikely to do me any good.

“Everything is going to be good” was the gist of the messages delivered to my mother while she lay on a bed in the hallway of the hospital, alone, unanesthetized, and ready to give birth to her first child, although I would later learn that I was not my father’s first child. My father was not allowed to be with her during her very long labor, but at least he managed to send encouraging notes.

Esther Brucha Safran. I was named for my two murdered grandmothers: my mother’s mother, Esther Weinberg Bronstein, and my father’s mother, Brucha Bisker Safran Kuperschmit. By coincidence it was also Purim, the celebration of Queen Esther, the unexpected queen of ancient Persia, who saved the Jews.

My name may have been intended to keep the memory of my grandmothers alive, but I seemed to intuitively understand from the beginning that my role was to bring joy. To point my family toward a brighter future while carrying with me the names of two murdered grandmothers. Whether I succeeded I can’t say with certainty, but I have tried.

It must have seemed a miracle to my father—a baby girl, alive, with a chest that could rise and fall, after his first daughter, the one he never spoke of to me, was murdered.