Полная версия:

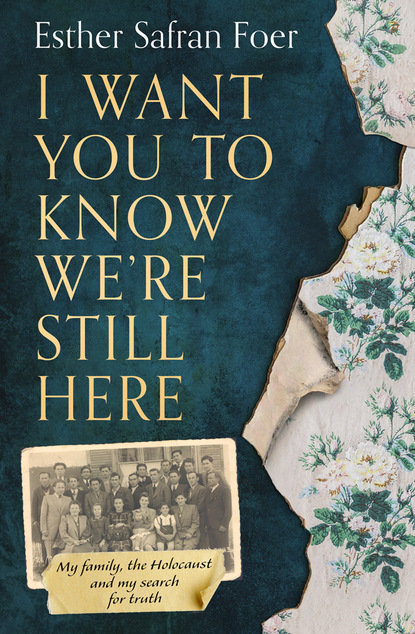

I Want You to Know We’re Still Here

Other stories began to emerge, often toggling between harrowing war stories and the minutiae of everyday life. The horrors become familiar with time, but the banal details can take on an almost magical quality, which might account for the instinct of artists to make the shtetl into a fairy tale.

It was a wonderful little town with nice people. Plain people. Hardworking.

We had a library. We had a doctor. We had a dentist.

The houses were made of brick.

And of wood.

They were nice houses.

Next door to us lived two brothers.

They were butchers.

We had horses.

And wagons.

We had nice clothes and beautiful shoes.

On the Sabbath, there was chicken, beef sometimes, turkey maybe twice a year for the big holidays.

Schmaltz was a big thing. Here, you don’t want the fat, you throw it away. There, when you go to the butcher—I remember this—they used to beg the butcher should give them a little bit of fat …

And Trochenbrod, where I went once in a while, in the summer, because there was everything: fresh milk, fresh sour cream, like yogurt. Smetana. From the smetana you made butter … Very tasty … everything was fresh there, fruits …

We continued to press my mother for details, sometimes conducting formal interviews. Frank decided to write about his grandmother for his high school senior project, and over the course of six weeks in 1992 he spent several days each week with her, a tape recorder running as he took her shopping, with all of those coupons in hand, in search of that week’s bargains. She has also been interviewed by volunteers from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, by writers and filmmakers, by other family members, and by an anthropologist cousin, who was interested in details on Kolki. I have hours and hours of taped interviews done during different stages in her life.

There were recurring motifs: the winter coat, the sister who ran after her, the pair of shoes. Beautiful Lifsha, my mother’s twenty-five-year-old half sister, and Lifsha’s two daughters, and her husband, David Shuster, who had been conscripted into the Polish army to fight the Nazis.

My mother remembered going with Lifsha and the rest of the family to see David off. “We all cried and cried,” my mother said, “because we thought we might never see him again.”

David survived; Lifsha and their daughters did not. Lifsha was killed in such a terrible way that my mother hesitated to speak of it, until she did, cryptically, referring to a million rapes. It’s not entirely clear to me when Lifsha died, but from what I have been able to piece together, she was one of the first killed in the initial days of the invasion, as was my mother’s maternal grandfather, Yosef Weinberg. He had been in one of the four synagogues in the village for morning prayers when the Nazis came. The doors were bolted and the synagogue set on fire.

Pesha and her mother, Esther, and her paternal grandmother Chava, along with Lifsha’s daughters, ages two and five, were taken to a ghetto set up for Jews, where they survived for about a year. Pesha managed to sneak out of the ghetto to see whether she could trade some silver spoons for food for the family and was shot on sight. Not long after, Chava and Esther, each holding one of Lifsha’s children in their arms, were shot over an open pit.

And then, amid the horror of these awful stories, my mother took a poignant detour:

Before the war, there had been a man. A dentist. He asked her to go for a ride in his canoe, but she did not go, even though she liked him. He came to visit her, but nothing happened—she seemed both intrigued and a little frightened by his attention. He was about ten years older—or maybe five or maybe twenty years older. The age gap seemed to vary with each rendering of the story, and once she opened up about it, I heard it many times. I might ask my mother a question about the river and it would lead her back to the dentist, the man who asked her to go with him for a ride in the canoe.

And here—in this man with his boat—it is possible to see the genesis of just about every sweeping wartime love story. Apparently, there was another, more serious boyfriend, who at some point later, after the war, after he enlisted to take revenge on the Nazis, after he was badly wounded, somehow managed to find Ethel’s address, to write, or have someone else write, a postcard with the message: “Don’t wait for me. Go and get married.” And she did. She married and she buried her husband and then she married again, and somehow, after my mother had been maybe fifteen or twenty years in the States, this man’s sister, remarkably, found Ethel and told her what had happened to him. “For two, three days I couldn’t eat,” my mother said.

What had happened to him? I don’t know. It’s one of many questions, another fragment of another story, that I’ll never have an answer to.

Even with just these sketchy details, I can still imagine the scene, my mother overcome with emotion, now remarried, living in suburban America, running a grocery store. She has children and stepchildren; she has a complicated and in many ways difficult life. And now this unexpected news from the past, information about a long-lost love. I can see the telephone receiver pressed to her ear, her fingers nervously playing with the long looping cord.

She communicates with the sister for a while, clandestinely. But then, whatever it is that is going on, she decides to let it go.

“This is what happened,” she says simply, years later. “You know, what a terrible war.”

I would later learn this was only one of my mother’s postwar suitors. David Shuster, who had been married to Lifsha, asked my mother to marry him after the war. This is an old Jewish shtetl tradition—a widower marries the unmarried younger sister. But my mother refused him; she told me she couldn’t marry her sister’s husband. David seemed to understand and was respectful of her answer—he even gave her money for a new coat.

They saw each other years later in Israel. By that time, David had remarried and he now had another daughter and a stepson. He told my mother that he always kept a hidden picture of Lifsha with him.

Kolki. It was a wonderful town, with nice, plain, hardworking people, my mother said.

In the prewar years, there were few cars. If one came through, everyone ran after it, because it was such a wonder.

There was no indoor plumbing and no electricity, except in two or three homes, including my great-grandfather’s—the one with the piano.

The ovens provided heat.

Water came from the nearby Styr River or from wells. If you could afford it, water was delivered by a man who carried it in buckets on his shoulders.

Laundry was washed by boiling some of this water on the stove.

Wednesday was market day, when most of the shopping took place. My mother described it as a kind of bazaar or flea market, where you could see everything from horses and cows to blueberries and butter. There were little stores, usually attached to people’s houses—tailors, shoemakers, bakers, carpenters—and a doctor and, of course, the dentist.

There were a number of different synagogues in Kolki—at least four small synagogues that my mother could remember, some organized by profession. For example, there was the schneider’s shul (the tailor’s synagogue) and one for the more prosperous merchants, like my mother’s rich grandfather, and there were synagogues based on the rabbi’s orientation. My mother, when asked, couldn’t remember ever actually going into one of the synagogues, although she recalled playing outside during the Jewish High Holidays.

My parents were born in the same region—in what is now western Ukraine and was then eastern Poland—but not the same town. Trochenbrod and Kolki were only about thirteen miles apart, and there were lots of family overlaps and visits between the towns.

There really is such a thing as Jewish geography. If you are a member of the tribe, you learn not to express surprise when you realize that your next-door neighbor is related to your best childhood friend or that his daughter has just married your cousin. Or that the boy in your son’s fourth-grade class is in fact a distant cousin.

“This town is a shtetl,” you might say. Except it’s more than just one town. It’s the world.

My mother had an anecdote she liked to tell about a visitor from the United States who was walking down the street in Kolki when a woman stuck her head out the window and yelled to him: “Do you know my Benjamin? He lives in New York.” As if America were such a small place that everyone knew everyone the way they did in Kolki. No punch line survives, but the answer could very well have been yes.

Like me, my mother had a confusing birth date. She knew that she was born in 1920 in Kolki on Lag B’Omer, a minor Jewish holiday that is considered a “happy day” in the middle of a period of sadness between Passover and Shavuot, a day for parties and bonfires. In the shtetl, dates were easy to mark if they coincided with a Jewish holiday. In 1920, Lag B’Omer fell on May 6. All of my mother’s official documents from the displaced-persons camps and her U.S. citizenship papers, however, show a birth date of June 15, 1920. When I pressed her on why the mix-up of dates for her and for me, she said that my father did it—that he scrambled all of the dates. In retrospect, since he clearly changed my birth date intentionally, my guess is he decided to mix up the others, as well.

Stories handed down from one generation to another change our behavior, but whether that leads to a desire to learn more or to silence the past, who can say. This question is central to a body of thought called postmemory, a term first introduced by writer and Columbia professor Marianne Hirsch. The idea is that traumatic memories live on from one generation to the next, even if the later generation was not there to experience these events directly. She suggests that the stories one grows up with are transmitted so affectively that they seem to constitute memories in their own right. That these inherited memories—traumatic fragments of events—defy narrative reconstruction.

Like so much else in our family story, scrambled birthdays seem to me one more detail, one more traumatic fragment of events that defy narrative reconstruction.

And yet piling fragment upon fragment is the best I can do, in the jars that line my mantel and in the story of my family, and it does add up to a picture that is something of a whole.

Like the recitation of names at a Yizkor service, a prayer for the departed, I am compelled to recite these fragments of my family history, to simply list the names, because sometimes that is the best we can do. There are no tombstones to mark the graves, so at least on these pages, the names reside.

There is my maternal great-grandmother Rose, or Reizel as she was called in Kolki, who would sometimes take my mother to Trochenbrod to visit her sister-in-law Sara Weinberg Bisker, who happened to be married to my father’s cousin.

And my mother’s older half sister, Lifsha, who was married to David Shuster. They met when he came from Trochenbrod to Kolki on business. Apparently, it was love at first sight. I have a number of pictures of Lifsha, with groups of friends, playing a balalaika, pictures with her husband and with one of their daughters, and a beautiful picture of her walking elegantly down the main street of Kolki with two of her aunts, her husband, David, her grandmother, and some cousins. “Shabbat walk in Kolki 1937” is written on the back of a photograph of a group of my female relatives, all of them wearing black, looking glamorous and carefree. If not for the inscription, I would have thought they were in Paris.

My mother’s parents were Esther Weinberg and Srulach Bronstein, or Braunshtein, depending on who is doing the spelling. They were both widowed, their first spouses having died of tuberculosis.

My widowed grandmother Esther had a son in her first marriage who died and whose name I don’t even know. My grandfather Srulach had a daughter, Lifsha, who became part of their new family.

Ethel, my mother, was the firstborn of my grandparents’ second marriage. Her life was a new start for this fractured family.

Four years after my mother was born, Esther and Srulach had another daughter, Pesha—she of the shoes. Pesha was the quiet child, which is about the most I could get out of my mother, who almost never talked about her younger sister, other than to keep going back to the shoes.

My grandmother Esther came from a religious family that lived in a dorf, or village, called Kolikovich (Kulikowicze), near Kolki, along the Styr River. It had only a handful of families, and my grandmother’s family may have been the only Jews.

My great-grandfather Yosef Weinberg was a tall, religious man, known for a fierce temper.

My great-grandmother Rose, or Reizel, was a tiny gentle woman, revered by her children and grandchildren. Like almost all of the Jews of Kolki, my great-grandparents and even my grandparents were related, either as cousins or through marriage.

My great-grandfather Yosef Weinberg’s first cousin Itzak Sahm was married to my great-grandmother Rose’s twin sister, Feiga.

Yosef and Rose’s oldest daughter, Chia, sister of my grandmother Esther, married one of my grandfather Srulach’s cousins. Two sisters married two cousins. And it goes on.

I wish I had more stories to attach to these names. A name is not a life, but sometimes it’s the best we can do, and even in flattened form, this recitation is my way of merging memory with history.

One night recently, when I couldn’t sleep, I went downstairs to my computer and started googling the name of the sanatorium in Poland where my maternal grandfather sought treatment and where he ultimately died. Remembering the name my mother had once mentioned, I tried several different spellings and finally stumbled on the TB sanatorium in Otwock, Poland, sixteen miles from Warsaw. The town apparently had a microclimate that made it a perfect place to treat patients with lung diseases. Isaac Bashevis Singer wrote about Otwock and its “crystal clear air.” Following several links, I found the Otwock Jewish cemetery, which had a database of graves. One of those graves was that of “Israel Shlomo Bronstein, son of Natan Tzvi,” whom we knew as Nissan. My grandfather’s nickname was Srulach, although his given name was Israel. He died on March 14, 1927, and to my surprise, the website included an actual picture of his tombstone. I had a match! Now I had the exact date of his death and even my grandfather’s middle name, Shlomo. I ran upstairs to tell Bert, who did not entirely share my enthusiasm in the middle of the night. My husband may be interested in my discoveries, but for him they can wait for sunrise.

As it happens, this is the only surviving tombstone of any of my immediate ancestors in all of Europe. Generations of my family lived in this part of the world, but all of their graves have either been destroyed or plowed over, or their bodies rest in mass graves, with no record of them anywhere other than in the Yad Vashem Holocaust database, if someone thought to enter their names.

My mother remained haunted all her life by the fact that she never said goodbye to her mother, who stood silently as she packed her things. She left without a plan. Just a winter coat, a pair of scissors, a change of clothes, and Pesha’s shoes.

In the town square, she joined four of her girlfriends, Sura Kleiman, Bryna Weiman, Kittle Dricker, and Sura Mechlin. Together they followed the retreating Russian army and stayed ahead of the approaching Germans. But the five women were quickly separated in the chaos of their exodus. Three remained together and my mother ended up with Sura Mechlin, the one she knew least well. They spent the rest of the war as virtual sisters. All five of them survived and built new lives in Israel, Canada, and, in my mother’s case, in the United States.

My mother and Sura traveled by horse-drawn wagon for a few days on the road east, with a Russian man my mother had worked with at a store in Kolki. But as the Soviet troops retreated, they saw the horse, wagon, and able-bodied young man and immediately requisitioned him. Before he left, however, he handed my mother a small suitcase and told her not to open it until he was gone. And here my mother did indeed have luck: The suitcase turned out to be filled with money that the man had taken from the store as he left. It was enough to get my mother and Sura started on their journey, even if it didn’t last long.

The two “new sisters” kept moving east, following the retreating army, sleeping in barns and fields at night. They figured out how to hide stolen potatoes in the lining of their pants. People they met along the way sometimes gave them food. From the farmers, a little milk and maybe honey. Sometimes they just had to go hungry.

One difficult day’s quest for survival led to another as they moved ever farther into Russia. They wandered the country for the ensuing three years, walking, hitching rides, sometimes hanging off trains. The grueling pace took a toll. My mother’s legs swelled from all the walking. At one point, she developed sores from malnutrition, and Sura tended to her, sometimes helping her to dress. They became dependent on each other as they traveled, eventually making their way into Asia and figuring out how to survive moment to moment.

During the war, about one million Jews from the former Soviet Union, including Poland, managed to escape into Russia, with a significant number making it all the way into Central Asia, like my mother and Sura. It has been estimated that about 300,000 of these died due to disease and starvation, while others died as Soviet soldiers.

“I was the lucky one,” my mother would say. “The others were in very, very bad shape, the ones I left behind.”

My mother was the boss, Sura told me years later, when I first met her in Israel in 1999. Sura brought me a Kiddush cup, celebrating life, from her home as a gift to remember her by.

“If there were just ten grains of rice to put in water to make soup, Ethel insisted we save two for the next day,” Sura said. They walked for miles, mostly by night, sometimes exchanging a little rice with local families for soap to wash themselves. My mother repeatedly told Sura that they had to save something so they could buy new dresses when they went home to see their families again.

They worked on farms and even in factories, making gun parts for the Soviet army. They found themselves in Kazakhstan and then, for a while, they worked in a city near Tashkent, Uzbekistan. The distance from Kolki to Tashkent is nearly 2,600 miles, if you use a direct route, about the same as the distance from New York to Los Angeles. Ethel and Sura hardly took a direct route, and much of the trip was on foot. But they were determined to make it, even as they watched people along the way giving up.

Sometime in 1944, when the war was not yet over, my mother and Sura heard that Kolki and neighboring shtetls had been liberated, so they immediately began to calculate how to go back home. They finally obtained a permit to leave Uzbekistan and go to the front lines in the west to offer medical support. Having survived this long, they had no interest in going to the front lines. Along the way they met a group of teenage Jewish girls who had become experts at forging documents and who produced falsified documents that would allow my mother and Sura to avoid the battles and go to Kolki.

They wrote a letter to Stalin—or at least he was the intended recipient—and somehow, somewhere, they received a letter from the Russian authorities saying all the Jews in Kolki had been killed. My mother and Sura refused to believe it. Even though the war wasn’t actually over, they went home.

When they finally arrived in Kolki, they met Sura’s brother-in-law, who had survived by hiding in the woods. He recounted everything that had happened to their families, person by person. After he told the handful of other returning survivors who returned to Kolki what had happened to their families, he left for Palestine, where, according to my mother, who met him years later, he literally never spoke another word.

I wish I knew more about him. I wish I had more details—my mother told me that she wished she’d had paper and pencil to record their journey, but she was too busy surviving. I can at least tell you what I know.

When they returned, my mother was able to identify her house—or her former house—which had been burned down; the wheel from the “oil factory” in the backyard was still there, sticking out of the ground.

As my mother wept, a woman on the other side of the street walked by, wearing her sister Lifsha’s dress. There was no mistaking the dress, because it had been sent by an American relative.

My mother and Sura wanted to say Kaddish for their families, but the mass grave was in the forest outside the village, and they were warned against going into the woods.

A neighbor my mother knew, seeing that she and Sura were hungry, offered them a meal that included a piece of meat. Sura ate, but my mother wouldn’t touch the meat. She recounted this story for Jonathan, when he was writing his book about vegetarianism, Eating Animals.

“He saved your life,” Jonathan said.

“I didn’t eat it.”

“You didn’t eat it?”

“It was pork. I wouldn’t eat pork.”

“Why?”

“What do you mean why?”

“What, because it wasn’t kosher?”

“Of course.”

“But not even to save your life?”

“If nothing matters, there’s nothing to save.”

3

My father’s story proved more difficult to excavate. He died when I was eight, an event that is still difficult for me to talk about. Even as I have pieced together a plausible history, he remains an enigma; the more I learn, the less I know, both about him and his experience during the war.

There are no pictures of my father growing up, none of his prewar family, of his parents, who are my grandparents. No pictures of his sister and her husband, who are my aunt and uncle.

Bits and pieces of information have come together over the years from cousins in Israel and from other Trochenbrod survivors, in Brazil and Israel, from conversations in Ukraine, and from documents that only recently were made available through the Holocaust Museum. I have utilized every available ancestry tool I could find and have located long-lost relatives as well as ones I didn’t know existed but none directly linked to my paternal grandfather’s family. I have pieced together an impressive archive, but the reality is that it is easier to find information on—or at least references to—the fictitious shtetl that sprang from Jonathan’s imagination than it is to find details about the place where my father actually lived.

I have come to accept that I will never know my father’s full story: how he survived the war, the precise details of what he endured, of what haunted him and continued to cast shadows even on the new life he made in America. What I do know is that solving the mystery of the black-and-white photograph of my father and the family that hid him during the war, and of finding Trochenbrod—or at least assembling fragments of events, piecing together a narrative of the sister that I never knew—has been, for me, the way of finding my father.

I am writing today in my chilly basement office, wrapped in my Trochenbrod hoodie. It was given to Jonathan on the movie set of his adapted novel, which, were one to write a fairy-tale end to this tragic story, would pretty much sum up how strange and unexpected this journey for my father’s past has proven to be.