Полная версия

Полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 3 (of 9)

I am, with great and sincere esteem, my dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO DR. GILMER

Philadelphia, December 15, 1792.Dear Doctor,—I received only two days ago your favor of October 9, by Mr. Everett. He is now under the small-pox. I am rejoiced with the account he gives me of the invigoration of your system, and am anxious for your persevering in any course of regimen which may long preserve you to us. We have just received the glorious news of the Prussian army being obliged to retreat, and hope it will be followed by some proper catastrophe on them. This news has given wry faces to our monocrats here, but sincere joy to the great body of the citizens. It arrived only in the afternoon of yesterday, and the bells were rung and some illuminations took place in the evening. A proposition has been made to Congress to begin sinking the public debt by a tax on pleasure horses; that is to say, on all horses not employed for the draught or farm. It is said there is not a horse of that description eastward of New York. And as to call this a direct tax would oblige them to proportion it among the States according to the census, they choose to class it among the indirect taxes. We have a glimmering hope of peace from the northern Indians, but from those of the south there is danger of war. Wheat is at a dollar and a fifth here. Do not sell yours till the market begins to fall. You may lose a penny or two in the bushel then, but might lose a shilling or two now. Present me affectionately to Mrs. Gilmer. Yours, sincerely.

TO MR. MERCER

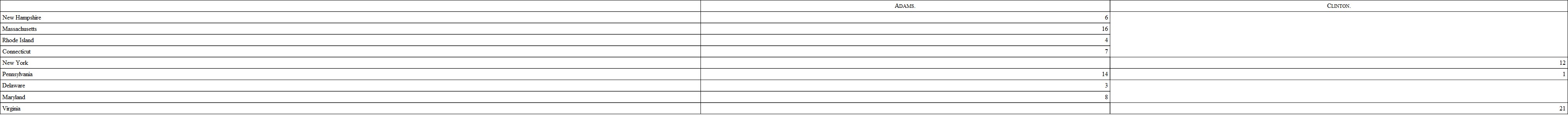

Philadelphia, December 19, 1792.Dear Sir,—I received yesterday your favor of the 13th. I had been waiting two or three days in expectation of vessels said to be in the river, and by which we hope more particular accounts of the late affairs in France. It has turned out that there were no such vessels arriving as had been pretended. However I think we may safely rely that the Duke of Brunswick has retreated, and it is certainly possible enough that between famine, disease, and a country abounding with defiles, he may suffer some considerable catastrophe. The monocrats here still affect to disbelieve all this, while the republicans are rejoicing and taking to themselves the name of Jacobins, which two months ago was fixed on them by way of stigma. The votes for Vice-President, as far as hitherto known, stands thus:

Bankrupt bill is brought on with some very threatening features to landed and farming men, who are in danger of being drawn into its vortex. It assumes the right of seizing and selling lands, and so cuts the knotty question of the Constitution whether the General Government may direct the transmission of land by descent or otherwise. The post-office is not within my department, but that of the treasury. I note duly what you say of Mr. Skinner, but I don't believe any bill on weights and measures will be passed. Adieu. Yours, affectionately.

TO MR. RUTHERFORD

Philadelphia, December 25, 1792.Sir,—I have considered, with all the attention which the shortness of the time would permit, the two motions which you were pleased to put into my hands yesterday afternoon, on the subject of weights and measures, now under reference to a committee of the Senate, and will take the liberty of making a few observations thereon.

The first, I presume, is intended as a basis for the adoption of that alternative of the report on measures and weights, which proposed retaining the present system, and fixing its several parts by a reference to a rod vibrating seconds, under the circumstances therein explained; and to fulfil its object, I think the resolutions there proposed should be followed by this: "that the standard by which the said measures of length, surface, and capacity shall be fixed, shall be an uniform cylindrical rod of iron, of such length as in latitude forty-five degrees, in the level of the ocean, and in a cellar or other place of uniform natural temperature, shall perform its vibrations in small and equal arcs, in one second of mean time; and that rain water be the substance, to some definite mass of which, the said weights shall be referred." Without this, the committee employed to prepare a bill on those resolutions, would be uninstructed as to the principles by which the Senate mean to fix their measures of length, and the substance by which they will fix their weights.

The second motion is a middle proposition between the first and the last alternatives in the report. It agrees with the first in some of the present measures and weights, and with the last, in compounding and dividing them decimally. If this should be thought best, I take the liberty of proposing the following alterations of these resolutions:

2d. For "metal" substitute "iron." The object is to have one determinate standard. But the different metals having different degrees of expansibility, there would be as many different standards as there are metals, were that generic term to be used. A specific one seems preferable, and "iron" the best, because the least variable by expansion.

3d. I should think it better to omit the chain of 66 feet, because it introduces a series which is not decimal, viz., 1. 66. 80. and because it is absolutely useless. As a measure of length, it is unknown to the mass of our citizens; and if retained for the purpose of superficial measure, the foot will supply its place, and fix the acre as in the fourth resolution.

4th. For the same reason, I propose to omit the words "or shall be ten chains in length and one in breadth."

5th. This resolution would stand better, if it omitted the words "shall be one foot square, and one foot and twenty cents of a foot deep, and," because the second description is perfect, and too plain to need explanation. Or if the first expression be preferred, the second may be omitted, as perfectly tautologous.

6th. I propose to leave out the words "shall be equal to the pound avoirdupois now in use, and," for the reasons suggested in the second resolution, to wit, that our object is, to have one determinate standard. The pound avoirdupois now in use is an indefinite thing. The committee of parliament reported variations among the standard weights of the exchequer. Different persons weighing the cubic foot of water, have made it, some more, and some less than one thousand ounces avoirdupois; according as their weights had been tested by the lighter or heavier standard weights of the exchequer. If the pound now in use be declared a standard, as well as the weight of sixteen thousand cubic cents of a foot in water, it may hereafter perhaps be insisted that these two definitions are different, and that, being of equal authority, either may be used, and so the standard pound be rendered as uncertain as at present.

7th. For the same reason, I propose to omit the words "equal to seven grains troy." The true ratio between the avoirdupois and troy weights, is a very contested one. The equation of seven thousand grains troy to the pound avoirdupois, is only one of several opinions, and is indebted perhaps to its integral form for its prevalence. The introduction either of the troy or avoirdupois weight into the definition of our unit, will throw that unit under the uncertainties now enveloping the troy and avoirdupois weights.

When the House of Representatives were pleased to refer to me the subject of weights and measures, I was uninformed as to the hypothesis on which I was to take it up; to wit, whether on that, that our citizens would not approve of any material change in the present system, or on the other, that they were ripe for a complete reformation. I therefore proposed plans for each alternative. In contemplating these, I had occasion to examine well all the middle ground between the two, and among others which presented themselves to my mind, was the plan of establishing one of the known weights and measures as the unit in each class; to wit, in the measures of lines, of surfaces, and of solids, and in weights, and to compound and divide them decimally. In the measures of weights, I had thought of the ounce as the best unit, because, calling it the thousandth part of a cubic foot of water, it fell into the decimal series, formed a happy link of connection with the system of measures on the one side, and of coins on the other, by admitting an equality with the dollar, without changing the value of that or its alloy materially. But on the whole, I abandoned this middle proposition, on the supposition that if our fellow citizens were ripe for advancing so great a length towards reformation, as to retain only four known points of the very numerous series to which they were habituated, to wit, the foot, the acre, the bushel, and the ounce, abandoning all the multiples and subdivisions of them, or recurring for their value to the tables which would be formed, they would probably be ripe for taking the whole step, giving up these four points also, and making the reformation complete; and the rather, as in the present series and the one to be proposed, there would be so many points of very near approximation, as aided in the same manner by tables, would not increase their difficulties perhaps, indeed, would lessen them by the greater simplicity of the links by which the several members of the system are connected together. Perhaps, however, I was wrong in this supposition. The representatives of the people in Congress are alone competent to judge of the general disposition of the people, and to what precise point of reformation they are ready to go. On this, therefore, I do not presume to give an opinion, nor to pronounce between the comparative expediency of the three propositions; but shall be ready to give whatever aid I can to any of them which shall be adopted by the Legislature.

I have the honor to be, with perfect respect, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO MR. PINCKNEY

Philadelphia, December 30, 1792.Dear Sir,—My last letters to you have been of the 13th and 20th of November, since which I have received yours of September 19. We are anxious to hear that the person substituted in the place of the one deceased is gone on that business. You do not mention your prospect of finding for the mint the officers we were desirous of procuring. On this subject, I will add to what was before mentioned to you, that if you can get artists really eminent, and on the salaries fixed by the law, we shall be glad of them; but that experience of the persons we have found here, would induce us to be contented with them rather than to take those who are not eminent, or who would expect more than the legal salaries. A greater difficulty has been experienced in procuring copper for the mint than we expected. Mr. Rittenhouse, the Director, having been advised that it might be had on advantageous terms from Sweden, has written me a letter on that subject, a copy of which I enclose you, with the bill of exchange it covered. I should not have troubled you with them, had our resident in Holland been in place. But on account of his absence, I am obliged to ask the favor of you to take such measures as your situation will admit, for procuring such a quantity of copper, to be brought us from Sweden, as this bill will enable you. It is presumed that the commercial relations of London with every part of Europe will furnish ready means of executing this commission. We as yet get no answer from Mr. Hammond on the general subject of the execution of the treaty. He says he is waiting for instructions. It would be well to urge, in your conversations with the minister, the necessity of giving Mr. Hammond such instructions and latitude as will enable him to proceed of himself. If on every move we are to await new instructions from the other side the Atlantic, it will be a long business indeed. You express a wish in your letter to be generally advised as to the tenor of your conduct, in consequence of the late revolution in France, the questions relative to which, you observe, incidentally present themselves to you. It is impossible to foresee the particular circumstances which may require you to decide and act on that question. But, principles being understood, their application will be less embarrassing. We certainly cannot deny to other nations that principle whereon our government is founded, that every nation has a right to govern itself internally under what forms it pleases, and to change these forms at its own will; and externally to transact business with other nations through whatever organ it chooses, whether that be a King, Convention, Assembly, Committee, President, or whatever it be. The only thing essential is, the will of the nation. Taking this as your polar star, you can hardly err. I shall send you by the first vessel which sails (the packet excepted on account of postage) two dozen plans of the city of Washington in the Federal Government, which you are desired to display, not for sale, but for public inspection, wherever they may be most seen by those descriptions of people worthy and likely to be attracted to it, dividing the plans among the cities of London and Edinburgh chiefly, but sending some also to Glasgow, Bristol, Dublin, &c. Mr. Taylor tells me he sends you the public papers by every vessel going from hence to London. They will keep you informed of the proceedings of Congress, and other occurrences worthy your knowledge. I have the honor to be, with great and sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

P. S. Though I have mentioned Sweden as the most likely place to get copper from, on the best terms, yet if you can be satisfied it may be got on better terms elsewhere, it is left to your discretion to get it elsewhere.

TO MR. SHORT

Philadelphia, January 3, 1793.Dear Sir,—My last private letter to you was of October 16, since which I have received your Nos. 103, 107, 108, 109, 110, 112, 113 and 114 and yesterday your private one of September 15, came to hand. The tone of your letters had for some time given me pain, on account of the extreme warmth with which they censured the proceedings of the Jacobins of France. I considered that sect as the same with the Republican patriots, and the Feuillants as the Monarchical patriots, well known in the early part of the Revolution, and but little distant in their views, both having in object the establishment of a free constitution, differing only on the question whether their chief Executive should be hereditary or not. The Jacobins (as since called) yielded to the Feuillants, and tried the experiment of retaining their hereditary Executive. The experiment failed completely, and would have brought on the re-establishment of despotism had it been pursued. The Jacobins knew this, and that the expunging that office was of absolute necessity. And the nation was with them in opinion, for however they might have been formerly for the constitution framed by the first assembly, they were come over from their hope in it, and were now generally Jacobins. In the struggle which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent. These I deplore as much as any body, and shall deplore some of them to the day of my death. But I deplore them as I should have done had they fallen in battle. It was necessary to use the arm of the people, a machine not quite so blind as balls and bombs, but blind to a certain degree. A few of their cordial friends met at their hands the fate of enemies. But time and truth will rescue and embalm their memories, while their posterity will be enjoying that very liberty for which they would never have hesitated to offer up their lives. The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed I would have seen half the earth desolated; were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than as it now is. I have expressed to you my sentiments, because they are really those of ninety-nine in an hundred of our citizens. The universal feasts, and rejoicings which have lately been had on account of the successes of the French, showed the genuine effusions of their hearts. You have been wounded by the sufferings of your friends, and have by this circumstance been hurried into a temper of mind which would be extremely disrelished if known to your countrymen. The rescue of 224.68.1460.916.83. had never permitted me to discover the light in which he viewed it, and as I was more anxious that you should satisfy him than me, I had still avoided explanations with you on the subject. But your 113. induced him to break silence, and to notice the extreme acrimony of your expressions. He added that he had been informed the sentiments you expressed in your conversations were equally offensive to our allies, and that you should consider yourself as the representative of your country, and that what you say might be imputed to your constituents. He desired me therefore to write to you on this subject. He added that he considered 729.633.224.939.1243. 1210.741.1683.1460.216.1407.890.1416.1212.674.125.633.1450. 1559.182. there are in the United States some characters of opposite principles; some of them are high in office, others possessing great wealth, and all of them hostile to France, and fondly looking to England as the staff of their hope. These I named to you on a former occasion. Their prospects have certainly not brightened. Excepting them, this country is entirely republican, friends to the Constitution, anxious to preserve it, and to have it administered according to its own republican principles. The little party above mentioned have espoused it only as a stepping-stone to monarchy, and have endeavored to approximate it to that in its administration in order to render its final transition more easy. The successes of republicanism in France have given the coup de grace to their prospects, and I hope to their projects. I have developed to you faithfully the sentiments of your country, that you may govern yourself accordingly. I know your republicanism to be pure, and that it is no decay of that which has embittered you against its votaries in France, but too great a sensibility at the partial evil which its object has been accomplished there. I have written to you in the style to which I have been always accustomed with you, and which perhaps it is time I should lay aside. But while old men are sensible enough of their own advance in years, they do not sufficiently recollect it in those whom they have seen young. In writing, too, the last private letter which will probably be written under present circumstances, in contemplating that your correspondence will shortly be turned over to I know not whom, but certainly to some one not in the habit of considering your interests with the same fostering anxieties I do, I have presented things without reserve, satisfied you will ascribe what I have said to its true motive, use it for your own best interest, and in that fulfil completely what I had in view. With respect to the subject of your letter of Sept. 15, you will be sensible that many considerations would prevent my undertaking the reformation of a system with which I am so soon to take leave. It is but common decency to leave to my successor the moulding of his own business. Not knowing how otherwise to convey this letter to you with certainty, I shall appeal to the friendship and honor of the Spanish commissioners here, to give it the protection of their cover, as a letter of private nature altogether. We have no remarkable event here lately but the death of Dr. Lee, nor have I anything new to communicate to you of your friends or affairs. I am, with unalterable affection and wishes for your prosperity, my dear Sir, your sincere friend and servant.

TO MR. RANDOLPH

Philadelphia, January 7, 1793.Dear Sir,—Our news from France continues to be good, and to promise a continuance; the event of the revolution there is now little doubted of, even by its enemies, the sensations it has produced here, and the indications of them in the public papers, have shown that the form our own government was to take depended much more on the events of France than anybody had before imagined. The tide which after our former relaxed government, took a violent course towards the opposite extreme, and seemed ready to hang everything round with the tassels and baubles of monarchy, is now getting track as we hope to a just mean, a government of laws addressed to the reason of the people and not to their weaknesses. The daily papers show it more than those you receive. An attempt in the House of Representatives to stop the recruiting service has been rejected. Indeed, the conferences for peace, agreed to by the Indians, do not promise much, as we have reason to believe they will insist on taking back lands purchased at former treaties. Maria is well; we hope all are so at Monticello. My best love to my dear Martha, and am, most affectionately, dear Sir, yours, &c.

TO MR. GALLATIN

Philadelphia, January 25, 1793.Sir,—Mr. Segaux called on me this morning to ask a statement of the experiment which was made in Virginia by a Mr. Mazzie, for the raising vines and making wines, and desired I would address it to you. Mr. Mazzie was an Italian, and brought over with him about a dozen laborers of his own country, bound to serve him four or five years. We made up a subscription for him of £2,000 sterling, and he began his experiment on a piece of land adjoining to mine. His intention was, before the time of his people should expire, to import more from Italy. He planted a considerable vineyard, and attended to it with great diligence for three years. The war then came on, the time of his people soon expired, some of them enlisted, others chose to settle on other lands and labor for themselves; some were taken away by the gentlemen of the country for gardeners, so that there did not remain a single one with him, and the interruption of navigation prevented his importing others. In this state of things he was himself employed by the State of Virginia to go to Europe as their agent to do some particular business. He rented his place to General Riedesel, whose horses in one week destroyed the whole labor of three or four years; and thus ended an experiment which, from every appearance, would in a year or two more have established the practicability of that branch of culture in America. This is the sum of the experiment as exactly as I am able to state it from memory, after such an interval of time, and I consign it to you in whose hands I know it will be applied with candor, if it contains anything applicable to the case for which it has been asked.

I have the honor to be, with great esteem and respect, Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO MRS. RANDOLPH

Philadelphia, January 26, 1793.My Dear Martha,—

* * * * *I have for some time past been under an agitation of mind which I scarcely ever experienced before, produced by a check on my purpose of returning home at the close of this session of Congress. My operations at Monticello had been all made to bear upon that point of time, my mind was fixed on it with a fondness which was extreme, the purpose firmly declared to the President, when I became assailed from all quarters with a variety of objections. Among these it was urged that my return just when I had been attacked in the public papers, would injure me in the eyes of the public, who would suppose I either withdrew from investigation, or because I had not tone of mind sufficient to meet slander. The only reward I ever wished on my retirement was to carry with me nothing like a disapprobation of the public. These representations have, for some weeks past, shaken a determination which I had thought the whole world could not have shaken. I have not yet finally made up my mind on the subject, nor changed my declaration to the President. But having perfect reliance in the disinterested friendship of some of those who have counseled and urged it strongly; believing that they can see and judge better a question between the public and myself than I can, I feel a possibility that I may be detained here into the summer. A few days will decide. In the meantime I have permitted my house to be rented after the middle of March, have sold such of my furniture as would not suit Monticello, and am packing up the rest and storing it ready to be shipped off to Richmond as soon as the season of good sea weather comes on. A circumstance which weighs on me next to the weightiest is the trouble which, I foresee, I shall be constrained to ask Mr. Randolph to undertake. Having taken from other pursuits a number of hands to execute several purposes which I had in view this year, I cannot abandon those purposes and lose their labor altogether. I must, therefore, select the most important and least troublesome of them, the execution of my canal, and (without embarrassing him with any details which Clarkson and George are equal to) get him to tell them always what is to be done and how, and to attend to the levelling the bottom; but on this I shall write him particularly if I defer my departure. I have not received the letter which Mr. Carr wrote to me from Richmond, nor any other from him since I left Monticello. My best affections to him, Mr. Randolph and your fireside, and am, with sincere love, my dear Martha, yours.