Полная версия

Полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 3 (of 9)

I shall avail myself of the opportunity by a vessel which is to sail in a few days, of sending proper information and instructions to our commissioners on the subject of the late, as well as of the future, interferences of the Spanish officers to our prejudice with the Indians, and for the establishment of common rules of conduct for the two nations.

I have the honor to be, with the most perfect respect and attachment, Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO MESSRS. CARMICHAEL AND SHORT

Philadelphia, November 3, 1792.Gentlemen,—I wrote you on the 14th of last month; since which some other incidents and documents have occurred, bearing relation to the subject of that letter. I therefore now enclose you a duplicate of that letter.

Copy of a letter from the Governor of Georgia, with the deposition it covered of a Mr. Hull, and an original passport, signed by Olivier, wherein he styles himself commissary for his Catholic Majesty with the Creeks.

Copy of a letter from Messrs. Viar and Jaudenes to myself, dated October the 29th, with that of the extract of a letter of September the 24th, from the Baron de Carondelet to them.

Copy of my answer of No. 1, to them, and copy of a letter from myself to the President, stating a conversation with those gentlemen.

From those papers you will find that we have been constantly endeavoring, by every possible means, to keep peace with the Creeks; that in order to do this, we have even suspended and still suspend the running a fair boundary between them and us, as agreed on by themselves, and having for its object the precise definition of their and our lands, so as to prevent encroachment on either side, and that we have constantly endeavored to keep them at peace with the Spanish settlements also; that Spain on the contrary, or at least the officers of her governments, since the arrival of the Baron de Carondelet, have undertaken to keep an agent among the Creeks, have excited them and the other southern Indians to commence a war against us, have furnished them with arms and ammunition for the express purpose of carrying on that war, and prevented the Creeks from running the boundary which would have removed the cause of difference from between us. Messrs. Viar and Jaudenes explain the ground of interference on the fact of the Spanish claim to that territory, and on an article in our treaty with the Creeks, putting themselves under our protection. But besides that you already know the nullity of their pretended claim to the territory, they had themselves set the example of endeavoring to strengthen that claim by the treaty mentioned in the letter of the Baron de Carondelet, and by the employment of an agent among them. The establishment of our boundary, committed to you, will, of course, remove the grounds of all future pretence to interfere with the Indians within our territory, and it was to such only that the treaty of New York stipulated protection; for we take for granted, that Spain will be ready to agree to the principle, that neither party has a right to stipulate protection or interference with the Indian nations inhabiting the territory of the other. But it is extremely material also, with sincerity and good faith, to patronize the peace of each other with the neighboring savages. We are quite disposed to believe that the late wicked excitements to war, have proceeded from the Baron de Carondelet himself, without any authority from his court. But if so, have we not reason to expect the removal of such an officer from our neighborhood, as an evidence of the disavowal of his proceedings? He has produced against us a serious war. He says in his letter, indeed, that he has suspended it. But this he has not done, nor possibly can he do it. The Indians are more easily engaged in a war than withdrawn from it. They have made the attack in force on our frontiers, whether with or without his consent, and will oblige us to a severe punishment of their aggression. We trust that you will be able to settle principles of a friendly concert between us and Spain, with respect to the neighboring Indians; and if not, that you will endeavor to apprize us of what we may expect, that we may no longer be tied up by principles, which, in that case, would be inconsistent with duty and self-preservation.

I have the honor to be, with sentiments of perfect esteem and respect, Gentlemen, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

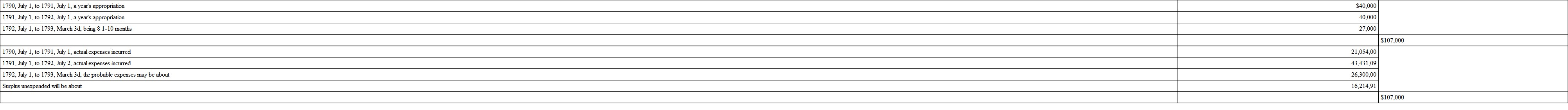

Philadelphia, November 3, 1792.Sir,—In order to enable you to lay before Congress the account required by law of the application of the moneys appropriated to foreign purposes through the agency of the Department of State, I have now the honor to transmit to you the two statements, Nos. 1 and 2, herein enclosed, comprehending the period of two years preceding the 1st day of July last.

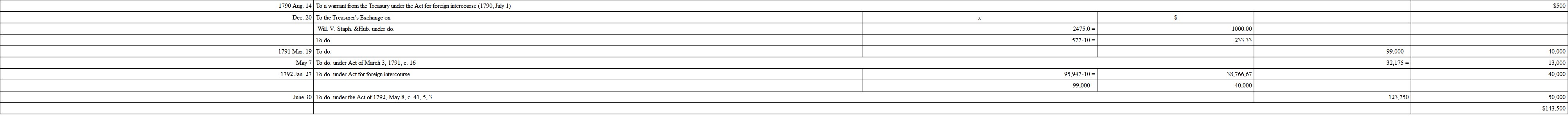

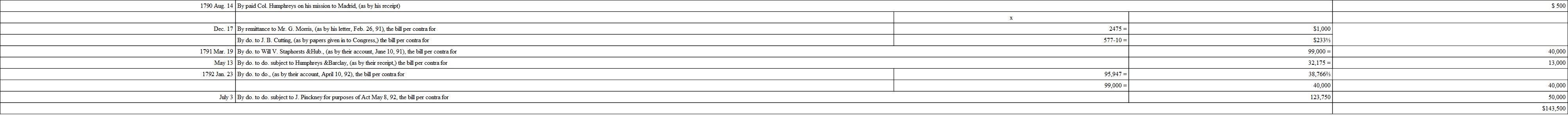

The first statement is of the sums paid from the Treasury under the act allowing the annual fund of $40,000 for the purpose of foreign intercourse, as also under the acts of March 3, 1791, c. 16, and May 1792, c. 41, 5, 3, allowing other sums for special purposes. By this it will appear, that, except the sum of $500 paid to Colonel Humphreys on his departure, the rest has all been received in bills of exchange, which identical bills have been immediately remitted to Europe, either to those to whom they were due for services, or to the bankers of the United States in Amsterdam, to be paid out by them to persons performing services abroad. This general view has been given in order to transfer the debt of these sums from the Department of State to those to whom they have been delivered.

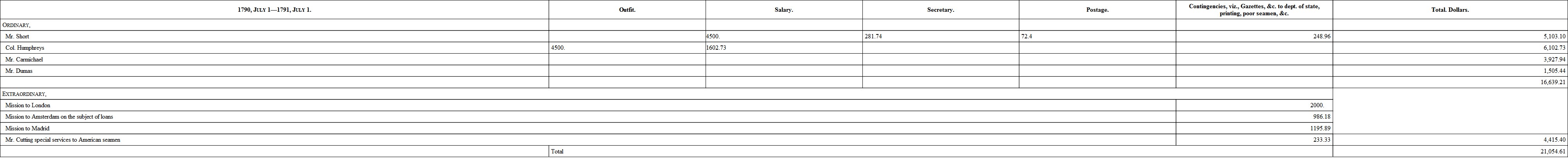

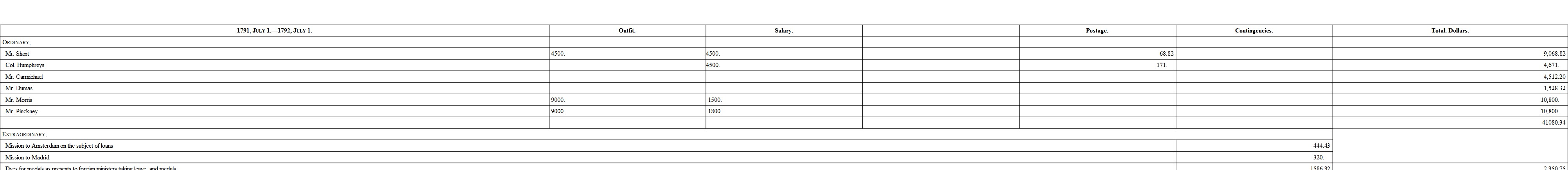

But in order to give to Congress a view of the specific application of these moneys, the particular accounts rendered by those who have received them, have been analyzed, and the payments made to them have been reduced under general heads, so as to show at one view the amount of the sums which each has received for every distinct species of service or disbursement, as well as their several totals. This is the statement No. 2, and it respects the annual fund of $40,000 only, the special funds of the acts of 1791 and 1792, having been not yet so far administered as to admit of any statement.

I had presented to the Auditor the statement No. 1, with the vouchers, and also the special accounts rendered by the several persons who have received these moneys, but, on consideration, he thought himself not authorized, by any law, to proceed to their examination. I am, therefore, to hope, Sir, that authority may be given to the Auditor, or some other person, to examine the general account and vouchers of the Department of State, as well as to raise special accounts against the persons into whose hands the moneys pass, and to settle the same from time to time on behalf of the public.

I have the honor to be, with sentiments of the most perfect respect and attachment, Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE IN ACCOUNT WITH THE U. S.

Dr.

Cr.

Analyses of the Expenses of the United States for their intercourse with Foreign Nations from July 1, 1790, to July 1, '91, and from July 1, '91, to July 1, '92, taken from the accounts of Messrs. Short, Humphreys, Morris, Pinckney, Willincks, Van Staphorsts, Hubbard, given to the auditor.

Thomas Jefferson having had the honor at different times heretofore of giving to the President conjectural estimate of expenses of our foreign establishment, has that of now laying before him, in page 1 of the enclosed paper, a statement of the whole amount of the foreign fund from the commencement to the expiration of the act, which will be on the 3d March next, with the actual expenses to the 1st of July last, and the conjectural ones from thence through the remaining eight months, and the balance which will probably remain.

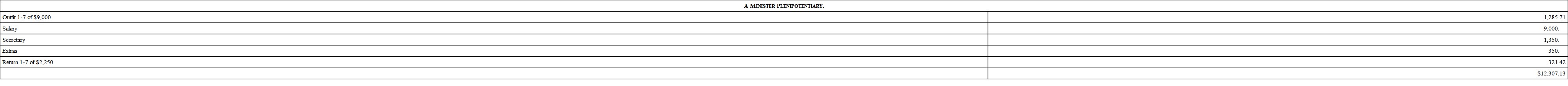

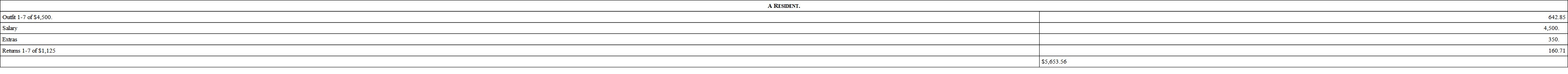

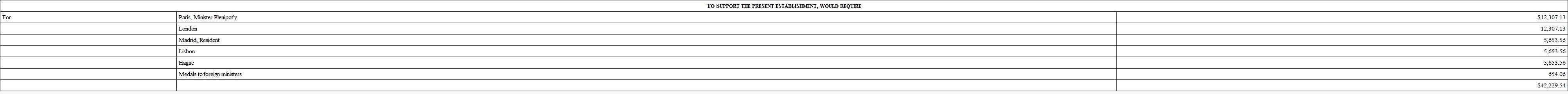

Page 2, shows the probable annual expense of our present establishment, and its excess above the funds allowed, and in another column the reduced establishment necessary and most proper to bring it within the limits of the funds supposing it should be continued.

November 5, 1792.

Estimate of the funds of $40,000 for foreign intercourse and its application.

November 5, 1792.

Estimate of the ordinary expense of the different diplomatic grades annually.

Medals to foreign ministers, suppose 5 to be kept here and changed once in 7 years, will be about $654.06 annually.

November 5, 1792.

Gentlemen of the Senate,—According to the directions of the law, I now lay before you a statement of the administration of the funds appropriated to certain foreign purposes, together with a letter from the Secretary of State, explaining the same.

November 5, 1792.

TO THE MAYOR, MUNICIPAL OFFICERS AND PROCUREUR OF THE COMMUNITY OF MARSEILLES

Philadelphia, November 6, 1792.Gentlemen,—Your letter of the 24th of August, is just now received by the President of the United States, and I have it in charge from him to communicate to you the particular satisfaction he feels at the expressions of fraternity towards our nation therein contained, to assure you that he desires sincerely the most speedy relief to France from her general difficulties, and will be happy to be instrumental in removing the special ones of the city of Marseilles in particular, by encouraging supplies of wheat and flour to be sent thither. Our harvest having been plentiful, our merchants would of course feel sufficient inducements, in the assurances you give of a ready sale and good price, were it not for the apprehensions of the Barbary cruisers. Certain arrangements for a Convoy, and the time, place, and manner of getting under its protection, would remove these apprehensions; but it may be doubtful whether these can be notified to them in time to prepare their adventures. They shall certainly, however, be informed of the wants of your city, and the inducements to go to it, and on this, and all other occasions, I beg leave to recommend our commerce to the patronage of your municipality, and to tender to you the homage of those sentiments of respect and attachment, with which I have the honor to be, Gentlemen, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO COLONEL HUMPHREYS

Philadelphia, November 6, 1792.Dear Sir,—We have never known so long an interval during which there has not been a single vessel going to Lisbon. Hence it is that I am so late in acknowledging the receipt of your letters from No. 54 to 58 inclusive, and that I am obliged to do it by the way of London, and consequently cannot send you the newspapers as usual.

The summer has been chiefly past in endeavoring to bring the north-western Indians to peace, and in preparing for a vigorous operation against them the ensuing summer, if peace should not be made. As yet no symptoms of it appear on their part. In the meantime there is danger of a war being kindled up on our south-western frontiers by the Indians in that quarter, excited, as we have reason to believe, by some Spanish officers. We trust that it has not been with the authority of their government.

To counterbalance these evils, we have had the blessing of another plentiful harvest of the principal grains. Tobacco and Indian corn have suffered from the early frosts. We have very earnest demands for supplies of grain from Marseilles; but the Algerine cruisers are an impediment. Would it be practicable for you, without awaiting a general treaty, to obtain permission for our flour to be carried to Portugal? nothing is more demonstrable than that this restriction is highly injurious to Portugal as well as to us.

Congress assembled yesterday, the President will meet them to-day, and I will enclose you a copy of his speech whereby you will see the chief objects which will be under their consideration during the present session. Your newspapers shall be sent by the very first vessel bound to Lisbon directly. I am, with sentiments of great and sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

P. S. November 7. After writing this letter, your No. 59 came to hand. It seems then that, so far from giving new liberties to our corn trade, Portugal contemplates the prohibition of it, by giving that trade exclusively to Naples. What would she say should we give her wine-trade exclusive to France and Spain. It is well known that far the greatest portion of the wine we consume, is from Portugal and its dependancies, and it must be foreseen that from the natural increase of population in these States, the demand will become equal to the uttermost abilities of Portugal to supply, even when her last foot of land shall be put into culture. Can a wise statesman seriously think of risking such a prospect as this? To me it seems incredible; and if the fact be so, I have no doubt you will interpose your opposition with the minister, developing to him all the consequences which such a measure would have on the happiness of the two nations. He should reflect that nothing but habit has produced in this country a preference of their wines over the superior wines of France, and that if once that habit is interrupted by an absolute prohibition it will never be recovered.

TO GOUVERNEUR MORRIS

Philadelphia, November 7, 1792.Dear Sir,—My last to you was of the 15th of October; since which I have received your Nos. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7. Though mine went by a conveyance directly to Bordeaux, and may therefore probably get safe to you, yet I think it proper, lest it should miscarry, to repeat to you the following paragraph from it.

* * * * *I am perfectly sensible that your situation must, ere this reaches you, have been delicate and difficult; and though the occasion is probably over, and your part taken of necessity, so that instructions now would be too late, yet I think it just to express our sentiments on the subject, as a sanction of what you have probably done. Whenever the scene became personally dangerous to you, it was proper you should leave it, as well from personal as public motives. But what degree of danger should be awaited, to what distance or place you should retire, are circumstances which must rest with your own discretion, it being impossible to prescribe them from hence. With what kind of government you may do business, is another question. It accords with our principles to acknowledge any government to be rightful, which is formed by the will of the nation substantially declared. The late government was of this kind, and was accordingly acknowledged by all the branches of ours. So, any alteration of it which shall be made by the will of the nation substantially declared, will doubtless be acknowledged in like manner. With such a government every kind of business may be done. But there are some matters which, I conceive, might be transacted with a government de facto; such, for instance, as the reforming the unfriendly restrictions on our commerce and navigation. Such cases you will readily distinguish as they occur. With respect to this particular reformation of their regulations, we cannot be too pressing for its attainment, as every day's continuance gives it additional firmness, and endangers its taking root in their habits and constitution; and, indeed, I think they should be told, as soon as they are in a condition to act, that if they do not revoke the late innovations, we must lay additional and equivalent burthens on French ships, by name. Your conduct in the case of M. de Bonne Carrere, is approved entirely. We think it of great consequence to the friendship of the two nations, to have a minister here in whose dispositions we have confidence. Congress assembled the day before yesterday. I enclose you a paper containing the President's speech, whereby you will see the chief objects of the present session. Your difficulties as to the settlements of our accounts with France and as to the payment of the foreign officers, will have been removed by the letter of the Secretary of the Treasury, of which, for fear it should have miscarried, I now enclose you a duplicate. Should a conveyance for the present letter offer to any port of France directly, your newspapers will accompany it. Otherwise, I shall send it through Mr. Pinckney, and retain the newspapers as usual, for a direct conveyance.

I am, with great and sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO COLONEL HUMPHREYS

Philadelphia, November 8, 1792.Dear Sir,—You were not unapprised of the reluctance with which I came into my present office, and I came into it with a determination to quit it as soon as decency would permit. Nor was it long before I fixed on the termination of our first federal cycle of four years as the proper moment. That moment is now approaching, and is to me as land was to Columbus in his first American voyage. The object of this private letter is to desire that your future public letters may be addressed to the Secretary of State by title and not by name, until you know who he will be, as otherwise your letters arriving here after the 3d of March, would incur the expense, delay, and risk of travelling six hundred miles by post after their arrival here. I may perhaps take the liberty of sometimes troubling you with a line from my retirement, and shall be ever happy to hear from you, and to give you every proof of the sincere esteem and respect, with which I have the honor to be, dear Sir, your affectionate friend and servant.

P. S. We yesterday received information of the conclusion of peace with the Wabash and Illinois Indians. This forms a broad separation between the northern and southern war-tribes.

TO T. M. RANDOLPH, JR

Philadelphia, November 16, 1792.Dear Sir,—Congress have not yet entered into any important business. An attempt has been made to give further extent to the influence of the Executive over the Legislature, by permitting the heads of departments to attend the House and explain their measures vivâ voce. But it was negatived by a majority of 35 to 11, which gives us some hope of the increase of the republican vote. However, no trying question enables us yet to judge, nor indeed is there reason to expect from this Congress many instances of conversion, though some will probably have been effected by the expression of the public sentiment in the late election. For, as far as we have heard, the event has been generally in favor of republican, and against the aristocratical candidates. In this State the election has been triumphantly carried by the republicans; their antagonists having got but 2 out of 11 members, and the vote of this State can generally turn the balance. Freneau's paper is getting into Massachusetts, under the patronage of Hancock; and Samuel Adams, and Mr. Ames, the colossus of the monocrats and paper men, will either be left out or hard run. The people of that State are republican; but hitherto they have heard nothing but the hymns and lauds chanted by Fenno. My love to my dear Martha, and am, dear Sir, yours affectionately.

TO M. DE TERNANT

Philadelphia, November 20, 1792.Sir,—Your letter on the subject of further supplies to the colony of St. Domingo, has been duly received and considered. When the distresses of that colony first broke forth, we thought we could not better evidence our friendship to that and to the mother country also, than to step in to its relief, on your application, without waiting a formal authorization from the National Assembly. As the case was unforeseen, so it was unprovided for on their part, and we did what we doubted not they would have desired us to do, had there been time to make the application, and what we presumed they would sanction as soon as known to them. We have now been going on more than a twelve-month, in making advances for the relief of the colony, without having, as yet, received any such sanction; for the decree of four millions of livres in aid of the colony, besides the circuitous and informal manner by which we became acquainted with it, describes and applies to operations very different from those which have actually taken place. The wants of the colony appear likely to continue, and their reliance on our supplies to become habitual. We feel every disposition to continue our efforts for administering to those wants; but that cautious attention to forms which would have been unfriendly in the first moment, becomes a duty to ourselves, when the business assumes the appearance of long continuance, and respectful also to the National Assembly itself, who have a right to prescribe the line of an interference so materially interesting to the mother country and the colony.

By the estimate you were pleased to deliver me, we perceive that there will be wanting, to carry the colony through the month of December, between thirty and forty thousand dollars, in addition to the sums before engaged to you. I am authorized to inform you, that the sum of forty thousand dollars shall be paid to your orders at the treasury of the United States, and to assure you, that we feel no abatement in our dispositions to contribute these aids from time to time, as they shall be wanting, for the necessary subsistence of the colony; but the want of express approbation from the national Legislature, must ere long produce a presumption that they contemplate perhaps other modes of relieving the colony, and dictate to us the propriety of doing only what they shall have regularly and previously sanctioned. Their decree before mentioned, contemplates purchases made in the United States only. In this they might probably have in view, as well to keep the business of providing supplies under a single direction, as that these supplies should be bought where they can be had cheapest, and where the same sum will consequently effect the greatest measure of relief to the colony. It is our wish as undoubtedly it must be yours, that the moneys we furnish be applied strictly in the line they prescribe. We understand, however, that there are in the hands of our citizens, some bills drawn by the administration of the colony, for articles of subsistence delivered there. It seems just, that such of them should be paid as were received before bona fide notice that that mode of supply was not bottomed on the funds furnished to you by the United States, and we recommend them to you accordingly.

I have the honor to be, with sentiments of the most perfect esteem and respect. Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO MR. PINCKNEY

Philadelphia, December 3, 1792.Dear Sir,—

* * * * *I do not write you a public letter by the packet because there is really no subject for it. The elections for Congress have produced a decided majority in favor of the republican interest. They complain, you know, that the influence and patronage of the Executive is to become so great as to govern the Legislature. They endeavored a few days ago to take away one means of influence by condemning references to the heads of department. They failed by a majority of five votes. They were more successful in their endeavor to prevent the introduction of a new means of influence, that of admitting the heads of department to deliberate occasionally in the House in explanation of their measures. The proposition for their admission was rejected by a pretty general vote. I think we may consider the tide of this government as now at the fullest, and that it will, from the commencement of the next session of Congress, retire and subside into the true principles of the Constitution. An alarm has been endeavored to be sounded as if the republican interest was indisposed to the payment of the public debt. Besides the general object of the calumny, it was meant to answer the special one of electioneering. Its falsehood was so notorious that it produced little effect. They endeavored with as little success to conjure up the ghost of anti-federalism, and to have it believed that this and republicanism were the same, and that both were Jacobinism. But those who felt themselves republicans and federalists too, were little moved by this artifice; so that the result of the election has been promising. The occasion of electing a Vice-President has been seized as a proper one for expressing the public sense on the doctrines of the monocrats. There will be a strong vote against Mr. Adams, but the strength of his personal worth and his services will, I think, prevail over the demerit of his political creed.