Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Tales from Dickens

This was a great grief to her at first, but on the day when Mr. Jarndyce came into her sick-room and held her in his arms and said, "My dear, dear girl!" she thought, "He has seen me and is fonder of me than before. So what have I to mourn for?" She thought of Allan Woodcourt, too, the young surgeon somewhere on the sea, and she was glad that, if he had loved her before he sailed away, he had not told her so. Now, she told herself, when they met again and he saw her so sadly changed he would have given her no promise he need regret.

When she was able to travel, Esther went for a short stay at the house of Mr. Boythorn, and there, walking under the trees she grew stronger.

One day, as she sat in the park that surrounded the house, she saw Lady Dedlock coming toward her, and seeing how pale and agitated she was, Esther felt the same odd sensation she had felt in the church. Lady Dedlock threw herself sobbing at her feet, and put her arms around her and kissed her, as she told her that she was her unhappy mother, who must keep her secret for the sake of her husband, Sir Leicester.

Esther thought her heart must break with both grief and joy at once. But she comforted Lady Dedlock, and told her nothing would ever change her love for her, and they parted with tears and kisses.

Another surprise of a different sort awaited Esther on her return to Bleak House. Mr. Jarndyce told her that he loved her and asked her if she would marry him. And, remembering how tender he had always been, and knowing that he loved her in spite of her disfigured face, she said yes.

But one day – the very day he returned – Esther saw Allan Woodcourt on the street. Somehow at the first glimpse of him she knew that she had loved him all along. Then she remembered that she had promised to marry Mr. Jarndyce, and she began to tremble and ran away without speaking to Woodcourt at all.

But they soon met, and this time it was Joe the crossing sweeper who brought them together. Woodcourt found the poor ragged wanderer in the street, so ill that he could hardly walk. He had recovered from smallpox, but it had left him so weak that he had become a prey to consumption. The kind-hearted surgeon took the boy to little Miss Flite and they found him a place to stay in Mr. George's shooting-gallery, where they did what they could for him, and where Esther and Mr. Jarndyce came to see him.

Joe was greatly troubled when he learned he had brought the smallpox to Bleak House, and one day he got some one to write out for him in very large letters that he was sorry and hoped Esther and all the others would forgive him. And this was his will.

On the last day Allan Woodcourt sat beside him, "Joe, my poor fellow," he said.

"I hear you, sir, but it's dark – let me catch your hand."

"Joe, can you say what I say?"

"I'll say anything as you do, sir, for I know it's good."

"Our Father."

"Our Father; yes, that's very good, sir."

"Which art in Heaven."

"Art in Heaven. Is the light a-comin', sir?"

"Hallowed be thy name."

"Hallowed be – thy – "

But the light had come at last. Little Joe was dead.

IV

ESTHER BECOMES THE MISTRESS OF BLEAK HOUSE

When the last bit of proof was fast in his possession Mr. Tulkinghorn, pluming himself on the cleverness with which he had wormed his way into Lady Dedlock's secret, went to her at her London home and informed her of all he had discovered, delighting in the fear and dread which she could not help showing. She knew now that this cruel man would always hold his knowledge over her head, torturing her with the threat of making it known to her husband.

Some hours after he had gone home, she followed him there to beg him not to tell her husband what he had discovered. But all was dark in the lawyer's house. She rang the private bell twice, but there was no answer, and she returned in despair.

By a coincidence some one else had been seen to call at Mr. Tulkinghorn's that same night. This was Mr. George, of the shooting-gallery, who came to get back the letter he had loaned to the lawyer.

When morning came it was found that a dreadful deed had been done that night. Mr. Tulkinghorn was found lying dead on the floor of his private apartment, shot through the heart. All the secrets he had so cunningly discovered and gloated over with such delight had not been able to save his life there in that room.

Mr. Tulkinghorn was so well-known that the murder made a great sensation. The police went at once to the shooting-gallery to arrest Mr. George and he was put into jail.

He was able later to prove his innocence, however, and, all in all, his arrest turned out to be a fortunate thing. For by means of it old Mrs. Rouncewell, Lady Dedlock's housekeeper, discovered that he was her own son George, who had gone off to be a soldier so many years before. He had made up his mind not to return till he was prospering. But somehow this time had never come; bad fortune had followed him and he had been ashamed to go back.

But though he had acted so wrongly he had never lost his love for his mother, and was glad to give up the shooting-gallery and go with Mrs. Rouncewell to become Sir Leicester's personal attendant.

At first, after the death of Mr. Tulkinghorn, Lady Dedlock had hoped that her dread and fear were now ended, but she soon found that this was not to be. The telltale bundle of letters was in the possession of a detective whom the cruel lawyer had long ago called to his aid, and the detective, thinking Lady Dedlock herself might have had something to do with the murder, thought it his duty to tell all that his dead employer had discovered to Sir Leicester.

It was a fearful shock to the haughty baronet to find so many tongues had been busy with the name his wife had borne so proudly. When the detective finished, Sir Leicester fell unconscious, and when he came to his senses had lost the power to speak.

They laid him on his bed, sent for doctors and went to tell Lady Dedlock, but she had disappeared.

Almost at one and the same moment the unhappy woman had learned not only that the detective had told his story to Sir Leicester, but that she herself was suspected of the murder. These two blows were more than she could bear. She put on a cloak and veil and, leaving all her money and jewels behind her, with a note for her husband, went out into the shrill, frosty wind. The note read:

"If I am sought for or accused of his murder, believe I am wholly innocent. I have no home left, I will trouble you no more. May you forget me and forgive me."

They gave Sir Leicester this note, and great agony came to the stricken man's heart. He had always loved and honored her, and he loved her no less now for what had been told him. Nor did he believe for a moment that she could be guilty of the murder. He wrote on a slate the words, "Forgive – find," and the detective started at once to overtake the fleeing woman.

He went first to Esther, to whom he told the sad outcome, and together they began the search. For two days they labored, tracing Lady Dedlock's movements step by step, through the pelting snow and wind, across the frozen wastes outside of London, where brick-kilns burned and where she had exchanged clothes with a poor laboring woman, the better to elude pursuit – then back to London again, where at last they found her.

But it was too late. She was lying frozen in the snow, at the gate of the cemetery where Captain Hawdon, the copyist whom she had once loved, lay buried.

So Lady Dedlock's secret was hidden at last by death. Only the detective, whose business was silence, Sir Leicester her husband, and Esther her daughter, knew what her misery had been or the strange circumstances of her flight, for the police soon succeeded in tracing the murder of Mr. Tulkinghorn to Hortense, the revengeful French maid whom he had threatened to put in prison.

One other shadow fell on Esther's life before the clouds cleared away for ever.

Grandfather Smallweed, rummaging among the papers in Krook's shop, found an old will, and this proved to be a last will made by the original Jarndyce, whose affairs the Court of Chancery had been all these years trying to settle. This will bequeathed the greater part of the fortune to Richard Carstone, and its discovery, of course, would have put a stop to the famous suit.

But the suit stopped of its own accord, for it was found now that there was no longer any fortune left to go to law about or to be willed to anybody. All the money had been eaten up by the costs.

After all the years of hope and strain, this disappointment was too much for Richard, and he died that night, at the very hour when poor crazed little Miss Flite (as she had said she would do when the famous suit ended) gave all her caged birds their liberty.

The time came at length, after the widowed Ada and her baby boy had come to make their home with Mr. Jarndyce, when Esther felt that she should fulfil her promise and become the mistress of Bleak House. So she told her guardian she was ready to marry him when he wished. He appointed a day, and she began to prepare her wedding-clothes.

But Mr. Jarndyce, true-hearted and generous as he had always been, had an idea very different from this in his mind. He had found, on Allan Woodcourt's return from his voyage, that the young surgeon still loved Esther. His keen eye had seen that she loved him in return, and he well knew that if she married him, Jarndyce, it would be because of her promise and because her grateful heart could not find it possible to refuse him. So, wishing most of all her happiness, he determined to give up his own love for her sake.

He bought a house in the town in which Woodcourt had decided to practise medicine, remodeled it and named it "Bleak House," after his own. When it was finished in the way he knew Esther liked best, he took her to see it, telling her it was to be a present from him to the surgeon to repay him for his kindness to little Joe.

Then, when she had seen it all, he told her that he had guessed her love for Woodcourt, and that, though she married the surgeon and not himself, she would still be carrying out her promise and would still become the mistress of "Bleak House."

When she lifted her tearful face from his shoulder she saw that Woodcourt was standing near them.

"This is 'Bleak House,'" said Jarndyce. "This day I give this house its little mistress, and, before God, it is the brightest day of my life!"

HARD TIMES

HARD TIMES

I

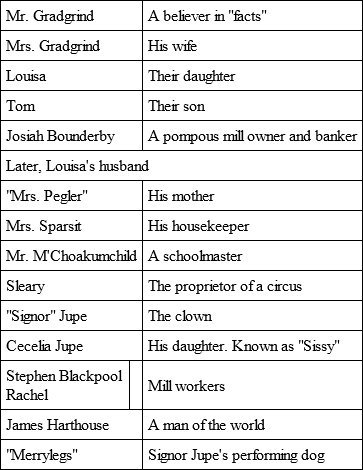

MR. GRADGRIND AND HIS "SYSTEM"

In a cheerless house called Stone Lodge, in Coketown, a factory town in England, where great weaving mills made the sky a blur of soot and smoke, lived a man named Gradgrind. He was an obstinate, stubborn man, with a square wall of a forehead and a wide, thin, set mouth. His head was bald and shining, covered with knobs like the crust of a plum pie, and skirted with bristling hair. He had grown rich in the hardware business, and was a school director of the town.

He believed in nothing but "facts." Everything in the world to him was good only to weigh and measure, and wherever he went one would have thought he carried in his pocket a rule and scales and the multiplication table. He seemed a kind of human cannon loaded to the muzzle with facts.

"Now, what I want is facts!" he used to say to Mr. M'Choakumchild, the schoolmaster. "Teach boys and girls nothing but facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Nothing else is of any service to anybody. Stick to facts, sir."

He had several children whom he had brought up according to this system of his, and they led wretched lives. No little Gradgrind child had ever seen a face in the moon, or learned Mother Goose or listened to fairy stories, or read The Arabian Nights. They all hated Coketown, always rattling and throbbing with machinery; they hated its houses all built of brick as red as an Indian's face, and its black canal and river purple with dyes. And most of all they hated facts.

Louisa, the eldest daughter, looked jaded, for her imagination was quite starved under their teachings. Tom, her younger brother, was defiant and sullen. "I wish," he used to say, "that I could collect all the facts and all the figures in the world, and all the people who found them out, and I wish I could put a thousand pounds of gunpowder under them and blow them all up together!"

Louisa was generous, and the only love she knew was for her selfish, worthless brother, who repaid her with very little affection. Of their mother they saw very little; she was a thin, white, pink-eyed bundle of shawls, feeble and ailing, and had too little mind to oppose her husband in anything.

Strangely enough, Mr. Gradgrind had once had a tender heart, and down beneath the facts of his system he had it still, though it had been covered up so long that nobody would have guessed it. Least of all, perhaps, his own children.

Mr. Gradgrind's intimate friend, – one whom he was foolish enough to admire, – was Josiah Bounderby, a big, loud, staring man with a puffed head whose skin was stretched so tight it seemed to hold his eyes open. He owned the Coketown mills and a bank besides, and was very rich and pompous.

Bounderby was a precious hypocrite, of an odd sort. His greatest pride was to talk continually of his former poverty and wretchedness, and he delighted to tell everybody that he had been born in a ditch, deserted by his wicked mother, and brought up a vagabond by a drunken grandmother – from which low state he had made himself wealthy and respected by his own unaided efforts.

Now, this was not in the least true. As a matter of fact, his grandmother had been a respectable, honest soul, and his mother had pinched and saved to bring him up decently, had given him some schooling, and finally apprenticed him in a good trade. But Bounderby was so ungrateful and so anxious to have people think he himself deserved all the credit, that after he became rich he forbade his mother even to tell any one who she was, and made her live in a little shop in the country forty miles from Coketown.

But in her good and simple heart the old woman was so proud of her son that she used to spend all her little savings to come into town, sometimes walking a good part of the way, cleanly and plainly dressed, and with her spare shawl and umbrella, just to watch him go into his fine house or to look in admiration at the mills or the fine bank he owned. On such occasions she called herself "Mrs. Pegler," and thought no one else would be the wiser.

The house in which Bounderby lived had no ornaments. It was cold and lonely and rich. He made his mill-hands more than earn their wages, and when any of them complained, he sneered that they wanted to be fed on turtle-soup and venison with a golden spoon.

Bounderby had for housekeeper a Mrs. Sparsit, who talked a great deal of her genteel birth, rich relatives and of the better days she had once seen. She was a busybody, and when she sat of an evening cutting out embroidery with sharp scissors, her bushy eyebrows and Roman nose made her look like a hawk picking out the eyes of a very tough little bird. In her own mind she had set her cap at Bounderby.

So firmly had Mr. Gradgrind put his trust in the gospel of facts which he had taught Louisa and Tom that he was greatly shocked one day to catch them (instead of studying any one of the dry sciences ending in "ology" which he made them learn) peeping through the knot holes in a wooden pavilion along the road at the performance of a traveling circus.

The circus, which was run by a man named Sleary, had settled itself in the neighborhood for some time to come, and all the performers meanwhile boarded in a near-by public house, The Pegasus's Arms. The show was given every day, and at the moment of Mr. Gradgrind's appearance one "Signor" Jupe, the clown, was showing the tricks of his trained dog, Merrylegs, and entertaining the audience with his choicest jokes.

Mr. Gradgrind, dumb with amazement, seized both Louisa and Tom and led them home, repeating at intervals, with indignation: "What would Mr. Bounderby say!"

This question was soon answered, for the latter was at Stone Lodge when they arrived. He reminded Mr. Gradgrind that there was an evil influence in the school the children attended, which no doubt had led them to such idle pursuits – this evil influence being the little daughter of Jupe, the circus clown. And Bounderby advised Mr. Gradgrind to have the child put out of the school at once.

The name of the clown's little daughter was Cecelia, but every one called her Sissy. She was a dark-eyed, dark-haired, appealing child, frowned upon by Mr. M'Choakumchild, the schoolmaster, because somehow many figures would not stay in her head at one time.

When the circus first came, her father, who loved her very much, had brought her to the Gradgrind house and begged that she be allowed to attend school. Mr. Gradgrind had consented. Now, however, at Bounderby's advice, he wished he had not done so, and started off with the other to The Pegasus's Arms to find Signor Jupe and deny to little Sissy the right of any more schooling.

Poor Jupe had been in great trouble that day. For a long time he had felt that he was growing too old for the circus business. His joints were getting stiff, he missed in his tumbling, and he could no longer make the people laugh as he had once done. He knew that before long Sleary would be obliged to discharge him, and this he thought he could not bear to have Sissy see.

He had therefore made up his mind to leave the company and disappear. He was too poor to take Sissy with him, so, loving her as he did, he decided to leave her there where at least she had some friends. He had come to this melancholy conclusion this very day, and had sent Sissy out on an errand so that he might slip away, accompanied only by his dog, Merrylegs, while she was absent.

Sissy was returning when she met Mr. Gradgrind and Bounderby, and came with them to find her father. But at the public house she met only sympathizing looks, for all of the performers had guessed what her father had done. They told her as gently as they could, but poor Sissy was at first broken-hearted in her grief and was comforted only by the assurance that her father would certainly come back to her before long.

While Sissy wept Mr. Gradgrind had been pondering. He saw here an excellent chance to put his "system" to the test. To take this untaught girl and bring her up from the start entirely on facts would be a good experiment. With this in view, then, he proposed to take Sissy to his house and to care for and teach her, provided she promised to have nothing further to do with the circus or its members.

Sissy knew how anxious her father had been to have her learn, so she agreed, and was taken at once to Stone Lodge and set to work upon facts.

But alas! Mr. Gradgrind's education seemed to make Sissy low-spirited, but no wiser. Every day she watched and longed for some message from her father, but none came. She was loving and lovable, and Louisa liked her and comforted her as well as she could. But Louisa was far too unhappy herself to be of much help to any one else.

Several years went by. Sissy's father had never returned. She had grown into a quiet, lovely girl, the only ray of light in that gloomy home. Mr. Gradgrind had realized one of his ambitions, had been elected to Parliament and now spent much time in London. Mrs. Gradgrind was yet feebler and more ailing. Tom had grown to be a young man, a selfish and idle one, and Bounderby had made him a clerk in his bank. Louisa, not blind to her brother's faults, but loving him devotedly, had become, in this time, an especial object of Bounderby's notice.

Indeed, the mill owner had determined to marry her. Louisa had always been repelled by his coarseness and rough ways, and when he proposed for her hand she shrank from the thought. If her father had ever encouraged her confidence she might then have thrown herself on his breast and told him all that she felt, but to Mr. Gradgrind marriage was only a cold fact with no romance in it, and his manner chilled her. Tom, in his utter selfishness, thought only of what a good thing it would be for him if his sister married his employer, and urged it on her with no regard whatever for her own liking.

At length, thinking, as long as she had never been allowed to have a sentiment that could not be put down in black and white, that it did not much matter whom she married after all, and believing that at least it would help Tom, she consented.

She married Bounderby, the richest man in Coketown, and went to live in his fine house, while Mrs. Sparsit, the housekeeper, angry and revengeful, found herself compelled to move into small rooms over Bounderby's bank.

II

THE ROBBERY OF BOUNDERBY'S BANK

In one of Bounderby's weaving mills a man named Stephen Blackpool had worked for years. He was sturdy and honest, but had a stooping frame, a knitted brow and iron-gray hair, for in his forty years he had known much trouble.

Many years before he had married; unhappily, for through no fault or failing of his own, his wife took to drink, left off work, and became a shame and a disgrace to the town. When she could get no money to buy drink with, she sold his furniture, and often he would come home from the mill to find the rooms stripped of all their belongings and his wife stretched on the floor in drunken slumber. At last he was compelled to pay her to stay away, and even then he lived in daily fear lest she return to disgrace him afresh.

What made this harder for Stephen to bear was the true love he had for a sweet, patient, working woman in the mill named Rachel. She had an oval, delicate face, with gentle eyes and dark, shining hair. She knew his story and loved him, too. He could not marry her, because his own wife stood in the way, nor could he even see or walk with her often, for fear busy tongues might talk of it, but he watched every flutter of her shawl.

One night Stephen went home to his lodging to find his wife returned. She was lying drunk across his bed, a besotted creature, stained and splashed, and evil to look at. All that night he sat sleepless and sick at heart.

Next day, at the noon hour, he went to his employer's house to ask his advice. He knew the law sometimes released two people from the marriage tie when one or the other lived wickedly, and his whole heart longed to marry Rachel.

But Bounderby told him bluntly that the law he had in mind was only for rich men, who could afford to spend a great deal of money. And he further added (according to his usual custom) that he had no doubt Stephen would soon be demanding the turtle-soup and venison and the golden spoon.

Stephen went home that night hopeless, knowing what he should find there. But Rachel had heard and was there before him. She had tidied the room and was tending the woman who was his wife. It seemed to Stephen, as he saw her in her work of mercy, there was an angel's halo about her head.

Soon the wretched creature she had aided passed out of his daily life again to go he knew not where, and this act of Rachel's remained to make his love and longing greater.

About this time a stranger came to Coketown. He was James Harthouse, a suave, polished man of the world, good-looking, well-dressed, with a gallant yet indolent manner and bold eyes.

Being wealthy, he had tried the army, tried a Government position, tried Jerusalem, tried yachting and found himself bored by them all. At last he had tried facts and figures, having some idea these might help in politics. In London he had met the great believer in facts, Mr. Gradgrind, and had been sent by him to Coketown to make the acquaintance of his friend Bounderby. Harthouse thus met the mill owner, who introduced him to Louisa, now his wife.

The year of married life had not been a happy one for her. She was reserved and watchful and cold as ever, but Harthouse easily saw that she was ashamed of Bounderby's bragging talk and shrank from his coarseness as from a blow. He soon perceived, too, that the only love she had for any one was given to Tom, though the latter little deserved it. In his own mind Harthouse called her father a machine, her brother a whelp and her husband a bear.