Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Tales from Dickens

It was in a quiet part of London that Lucie and her father lived, all alone save for the faithful Miss Pross. They had little furniture, for they were quite poor, but Lucie made the most of everything. Doctor Manette had recovered his mind, but not all of his memory. Sometimes he would get up in the night and walk up and down, up and down, for hours. At such times Lucie would hurry to him and walk up and down with him till he was calm again. She never knew why he did this, but she came to believe he was trying vainly to remember all that had happened in those lost years which he had forgotten. He kept his prison bench and tools always by him, but as time went on he gradually used them less and less often.

Mr. Lorry, with his flaxen wig and constant smile, came to tea every Sunday with them and helped to keep Doctor Manette cheerful. Sometimes Darnay, Sydney Carton and Mr. Lorry would meet there together, but of them all, Darnay came oftenest, and soon it was easy to see that he was in love with Lucie.

Sydney Carton, too, was in love with her, but he was perfectly aware that he was quite undeserving, and that Lucie could never love him in return. She was the last dream of his wild, careless life, the life he had wasted and thrown away. Once he told her this, and said that, although he could never be anything to her himself, he would give his life gladly to save any one who was near and dear to her.

Lucie fell in love with Darnay at length and one day they were married and went away on their wedding journey.

Until then, since his rescue, Lucie had never been out of Doctor Manette's sight. Now, though he was glad for her happiness, yet he felt the pain of the separation so keenly that it unhinged his mind again. Miss Pross and Mr. Lorry found him next morning making shoes at the old prison bench and for nine days he did not know them at all. At last, however, he recovered, and then, lest the sight of it affect him, one day when he was not there they chopped the bench to pieces and burned it up.

But her father was better after Lucie came back with her husband, and they took up their quiet life again. Darnay loved Lucie devotedly. He supported himself still by teaching. Mr. Lorry came from the bank oftener to tea and Sydney Carton more rarely, and their life was peaceful and content.

Once after his marriage, his cruel uncle, the Marquis de St. Evrémonde, sent for Darnay to come to France on family matters. Darnay went, but declined to remain or to do the other's bidding.

But his uncle's evil life was soon to be ended. While Darnay was there the marquis was murdered one night in his bed by a grief-crazed laborer, whose little child his carriage had run over.

Darnay returned to England, shocked and horrified the more at the indifference of the life led by his race in France. Although now, by the death of his uncle, he had himself become the Marquis de St. Evrémonde, yet he would not lay claim to the title, and left all the estates in charge of one of the house servants, an honest steward named Gabelle.

He had intended after his return to Lucie to settle all these affairs and to dispose of the property, which he felt it wrong for him to hold; but in the peace and happiness of his life in England he put it off and did nothing further.

And this neglect of Darnay's – as important things neglected are apt to prove – came before long to be the cause of terrible misfortune and agony to them all.

II

DARNAY CAUGHT IN THE NET

While these things were happening in London, the one city of this tale, other very different events were occurring in the other city of the story – Paris, the French capital.

The indifference and harsh oppression of the court and the nobles toward the poor had gone on increasing day by day, and day by day the latter had grown more sullen and resentful. All the while the downtrodden people of Paris were plotting secretly to rise in rebellion, kill the king and queen and all the nobles, seize their riches and govern France themselves.

The center of this plotting was Defarge, the keeper of the wine shop, who had cared for Doctor Manette when he had first been released from prison. Defarge and those he trusted met and planned often in the very room where Mr. Lorry and Lucie had found her father making shoes. They kept a record of all acts of cruelty toward the poor committed by the nobility, determining that, when they themselves should be strong enough, those thus guilty should be killed, their fine houses burned, and all their descendants put to death, so that not even their names should remain in France. This was a wicked and awful determination, but these poor, wretched people had been made to suffer all their lives, and their parents before them, and centuries of oppression had killed all their pity and made them as fierce as wild beasts that only wait for their cages to be opened to destroy all in their path.

They were afraid, of course, to keep any written list of persons whom they had thus condemned, so Madame Defarge, the wife of the wine seller, used to knit the names in fine stitches into a long piece of knitting that she seemed always at work on.

Madame Defarge was a stout woman with big coarse hands and eyes that never seemed to look at any one, yet saw everything that happened. She was as strong as a man and every one was somewhat afraid of her. She was even crueler and more resolute than her husband. She would sit knitting all day long in the dirty wine shop, watching and listening, and knitting in the names of people whom she hoped soon to see killed.

One of the hated names that she knitted over and over again was "Evrémonde." The laborer who, in the madness of his grief for his dead child, had murdered the Marquis de St. Evrémonde, Darnay's hard-hearted uncle, had been caught and hanged; and, because of this, Defarge and his wife and the other plotters had condemned all of the name of Evrémonde to death.

Meanwhile the king and queen of France and all their gay and careless court of nobles feasted and danced as heedlessly as ever. They did not see the storm rising. The bitter taxes still went on. The wine shop of Defarge looked as peaceful as ever, but the men who drank there now were dreaming of murder and revenge. And the half-starved women, who sat and looked on as the gilded coaches of the rich rolled through the streets, were sullenly waiting – watching Madame Defarge as she silently knitted, knitted into her work names of those whom the people had condemned to death without mercy.

One day this frightful human storm, which for so many years had been gathering in France, burst over Paris. The poor people rose by thousands, seized whatever weapons they could get – guns, axes, or even stones of the street – and, led by Defarge and his tigerish wife, set out to avenge their wrongs. Their rage turned first of all against the Bastille, the old stone prison in which so many of their kind had died, where Doctor Manette for eighteen years had made shoes. They beat down the thick walls and butchered the soldiers who defended it, and released the prisoners. And wherever they saw one of the king's uniforms they hanged the wearer to the nearest lamp post. It was the beginning of the terrible Revolution in France that was to end in the murder of thousands of innocent lives. It was the beginning of a time when Paris's streets were to run with blood, when all the worst passions of the people were loosed, and when they went mad with the joy of revenge.

The storm spread over France – to the village where stood the great château of the Evrémonde family, and the peasants set fire to it and burned it to the ground. And Gabelle (the servant who had been left in charge by Darnay, the new Marquis de St. Evrémonde, whom they had never seen, but yet hated) they seized and put in prison. They stormed the royal palace and arrested the king and queen, threw all who bore noble names or titles into dungeons, and, as they had planned, set up a government of their own.

Darnay, safe in London with Lucie, knew little and thought less of all this, till he received a pitiful letter from Gabelle, who expected each morning to be dragged out to be killed, telling of the plight into which his faithfulness had brought him, and beseeching his master's aid.

This letter made Darnay most uneasy. He blamed himself, because he knew it was his fault that Gabelle had been left so long in such a dangerous post. He did not forget that his own family, the Evrémondes, had been greatly hated. But he thought the fact that he himself had refused to be one of them, and had given his sympathy rather to the people they oppressed, would make it possible for him to obtain Gabelle's release. And with this idea he determined to go himself to Paris.

He knew the very thought of his going, now that France was mad with violence, would frighten Lucie, so he determined not to tell her. He packed some clothing hurriedly and left secretly, sending a letter back telling her where and why he was going. And by the time she read this he was well on his way from England.

Darnay had expected to find no trouble in his errand and little personal risk in his journey, but as soon as he landed on the shores of France he discovered his mistake. He had only to give his real name, "the Marquis de St. Evrémonde," which he was obliged to do if he would help Gabelle, and the title was the signal for rude threats and ill treatment. Once in, he could not go back, and he felt as if a monstrous net were closing around him (as indeed, it was) from which there was no escape.

He was sent on to Paris under a guard of soldiers, and there he was at once put into prison to be tried – and in all probability condemned to death – as one of the hated noble class whom the people were now killing as fast as they could.

The great room of the prison to which he was taken Darnay found full of ladies and gentlemen, most of them rich and titled, the men chatting, the women reading or doing embroidery, all courteous and polite, as if they sat in their own splendid homes, instead of in a prison from which most of them could issue only to a dreadful death. He was allowed to remain here only a few moments; then he was taken to an empty cell and left alone.

It happened that the bank of which Mr. Lorry was agent had an office also in Paris, and the old gentleman had come there on business the day before Darnay arrived. Mr. Lorry was an Englishman born, and for him there was no danger. He knew nothing of the arrest of Darnay until a day or two later, when, as he sat in his room, Doctor Manette and Lucie entered, just arrived from London, deeply agitated and in great fear for Darnay's safety.

As soon as Lucie had read her husband's letter she had followed at once with her father and Miss Pross. Doctor Manette, knowing Darnay's real name and title (for, before he married Lucie, he had told her father everything concerning himself), feared danger for him. But he had reasoned that his own long imprisonment in the Bastille – the building the people had first destroyed – would make him a favorite, and render him able to aid Darnay if danger came. On the way, they had heard the sad news of his arrest, and had come at once to Mr. Lorry to consider what might best be done.

While they talked, through the window they saw a great crowd of people come rushing into the courtyard of the building to sharpen weapons at a huge grindstone that stood there. They were going to murder the prisoners with which the jails were by this time full!

Fearful that he would be too late to save Darnay, Doctor Manette rushed to the yard, his white hair streaming in the wind, and told the leaders of the mob who he was – how he had been imprisoned for eighteen years in the Bastille, and that now one of his kindred, by some unknown error, had been seized. They cheered him, lifted him on their shoulders and rushed away to demand for him the release of Darnay, while Lucie, in tears, with Mr. Lorry and Miss Pross, waited all night for tidings.

But none came that night. The rescue had not proved easy. Next day Defarge, the wine shop keeper, brought a short note to Lucie from Darnay at the prison, but it was four days before Doctor Manette returned to the house. He had, indeed, by the story of his own sufferings, saved Darnay's life for the time being, but the prisoner, he had been told, could not be released without trial.

For this trial they waited, day after day. The time passed slowly and terribly. Prisoners were no longer murdered without trial, but few escaped the death penalty. The king and queen were beheaded. Thousands were put to death merely on suspicion, and thousands more were thrown into prison to await their turn. This was that dreadful period which has always since been called "The Reign of Terror," when no one felt sure of his safety.

There was a certain window in the prison through which Darnay sometimes found a chance to look, and from which he could see one dingy street corner. On this corner, every afternoon, Lucie took her station for hours, rain or shine. She never missed a day, and thus at long intervals her husband got a view of her.

So months passed till a year had gone. All the while Doctor Manette, now become a well-known figure in Paris, worked hard for Darnay's release. And at length his turn came to be tried and he was brought before the drunken, ignorant men who called themselves judge and jury.

He told how he had years before renounced his family and title, left France, and supported himself rather than be a burden on the peasantry. He told how he had married a woman of French birth, the only daughter of the good Doctor Manette, whom all Paris knew, and had come to Paris now of his own accord to help a poor servant who was in danger through his fault.

The story caught the fancy of the changeable crowd in the room. They cheered and applauded it. When he was acquitted they were quite as pleased as if he had been condemned to be beheaded, and put him in a great chair and carried him home in triumph to Lucie.

There was only one there, perhaps, who did not rejoice at the result, and that was the cold, cruel wife of the wine seller, Madame Defarge, who had knitted the name "Evrémonde" so many times into her knitting.

III

SYDNEY CARTON'S SACRIFICE

That same night of his release all the happiness of Darnay and Lucie was suddenly broken. Soldiers came and again arrested him. Defarge and his wife were the accusers this time, and he was to be retried.

The first one to bring this fresh piece of bad news to Mr. Lorry was Sydney Carton, the reckless and dissipated young lawyer. Probably he had heard, in London, of Lucie's trouble, and out of his love for her, which he always carried hidden in his heart, had come to Paris to try to aid her husband. He had arrived only to hear, at the same time, of the acquittal and the rearrest.

As Carton walked along the street thinking sadly of Lucie's new grief, he saw a man whose face and figure seemed familiar. Following, he soon recognized him as the English spy, Barsad, whose false testimony, years before in London, had come so near convicting Darnay when he was tried for treason. Barsad (who, as it happened, was now a turnkey in the very prison where Darnay was confined) had left London to become a spy in France, first on the side of the king and then on the side of the people.

At the time of this story England was so hated by France that if the people had known of Barsad's career in London they would have cut off his head at once. Carton, who was well aware of this, threatened the spy with his knowledge and made him swear that if worst came to worst and Darnay were condemned, he would admit Carton to the cell to see him once before he was taken to execution. Why Carton asked this Barsad could not guess, but to save himself he had to promise.

Next day Darnay was tried for the second time. When the judge asked for the accusation, Defarge laid a paper before him.

It was a letter that had been found when the Bastille fell, in the cell that had been occupied for eighteen years by Doctor Manette. He had written it before his reason left him, and hidden it behind a loosened stone in the wall; and in it he had told the story of his own unjust arrest. Defarge read it aloud to the jury. And this was the terrible tale it told:

The Marquis de St. Evrémonde (the cruel uncle of Darnay), when he was a young man, had dreadfully wronged a young peasant woman, had caused her husband's death and killed her brother with his own hand. As the brother lay dying from the sword wound, Doctor Manette, then also a young man, had been called to attend him, and so, by accident, had learned the whole. Horrified at the wicked wrong, he wrote of it in a letter to the Minister of Justice. The Marquis whom it accused learned of this, and, to put Doctor Manette out of the way, had him arrested secretly, taken from his wife and baby daughter and thrown into a secret cell of the Bastille, where he had lived those eighteen years, not knowing whether his wife and child lived or died. He waited ten years for release, and when none came, at last, feeling his mind giving way, he wrote the account, which he concealed in the cell wall, denouncing the family of Evrémonde and all their descendants.

The reading of this paper by Defarge, as may be guessed, aroused all the murderous passions of the people in the court room. There was a further reason for Madame Defarge's hatred, for the poor woman whom Darnay's uncle had so wronged had been her own sister! In vain old Doctor Manette pleaded. That his own daughter was now Darnay's wife made no difference in their eyes. The jury at once found Darnay guilty and sentenced him to die by the guillotine the next morning.

Lucie fainted when the sentence was pronounced. Sydney Carton, who had witnessed the trial, lifted her and bore her to a carriage. When they reached home he carried her up the stairs and laid her on a couch.

Before he went, he bent down and touched her cheek with his lips, and they heard him whisper: "For a life you love!"

They did not know until next day what he meant.

Carton had, in fact, formed a desperate plan to rescue Lucie's husband, whom he so much resembled in face and figure, even though it meant his own death. He went to Mr. Lorry and made him promise to have ready next morning passports and a coach and swift horses to leave Paris for England with Doctor Manette, Lucie and himself, telling him that if they delayed longer, Lucie's life and her father's also would be lost.

Next, Carton bought a quantity of a drug whose fumes would render a man insensible, and with this in his pocket early next morning he went to the spy, Barsad, and bade him redeem his promise and take him to the cell where Darnay waited for the signal of death.

Darnay was seated, writing a last letter to Lucie, when Carton entered. Pretending that he wished him to write something that he dictated, Carton stood over him and held the phial of the drug to his face. In a moment the other was unconscious. Then Carton changed clothes with him and called in the spy, directing him to take the unconscious man, who now seemed to be Sydney Carton instead of Charles Darnay, to Mr. Lorry's house. He himself was to take the prisoner's place and suffer the penalty.

The plan worked well. Darnay, who would not have allowed this sacrifice if he had known, was carried safely and without discovery, past the guards. Mr. Lorry, guessing what had happened when he saw the unconscious figure, took coach at once with him, Doctor Manette and Lucie, and started for England that very hour. Miss Pross was left to follow them in another carriage.

While Miss Pross sat waiting in the empty house, who should come in but the terrible Madame Defarge! The latter had made up her mind, as Carton had suspected, to denounce Lucie also. It was against the law to mourn for any one who had been condemned as an enemy to France, and the woman was sure, of course, that Lucie would be mourning for her husband, who was to die within the hour. So she stopped on her way to the execution to see Lucie and thus have evidence against her.

When Madame Defarge entered, Miss Pross read the hatred and evil purpose in her face. The grim old nurse knew if it were known that Lucie had gone, the coach would be pursued and brought back. So she planted herself in front of the door of Lucie's room, and would not let Madame Defarge open it.

The savage Frenchwoman tried to tear her away, but Miss Pross seized her around the waist, and held her back. The other drew a loaded pistol from her breast to shoot her, but in the struggle it went off and killed Madame Defarge herself.

Then Miss Pross, all of a tremble, locked the door, threw the key into the river, took a carriage and followed after the coach.

Not long after the unconscious Darnay, with Lucie and Doctor Manette, passed the gates of Paris, the jailer came to the cell where Sydney Carton sat and called him. It was the summons to die. And with his thoughts on Lucie, whom he had always hopelessly loved, and on her husband, whom he had thus saved to her, he went almost gladly.

A poor little seamstress rode in the death cart beside him. She was so small and weak that she feared to die, and Carton held her cold hand all the way and comforted her to the end. Cruel women of the people sat about the guillotine knitting and counting with their stitches, as each poor victim died. And when Carton's turn came, thinking he was Darnay, the hated Marquis de St. Evrémonde, they cursed him and laughed.

Men said of him about the city that night that it was the peacefullest man's face ever beheld there. If they could have read his thought, if he could have spoken it in words it would have been these:

"I see the lives, for which I lay down mine, peaceful and happy in that England I shall see no more. I see Lucie and Darnay with a child that bears my name, and I see that I shall hold a place in their hearts for ever. I see her weeping for me on the anniversary of this day. I see the blot I threw upon my name faded away, and I know that till they die neither shall be more honored in the soul of the other than I am honored in the souls of both. It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known!"

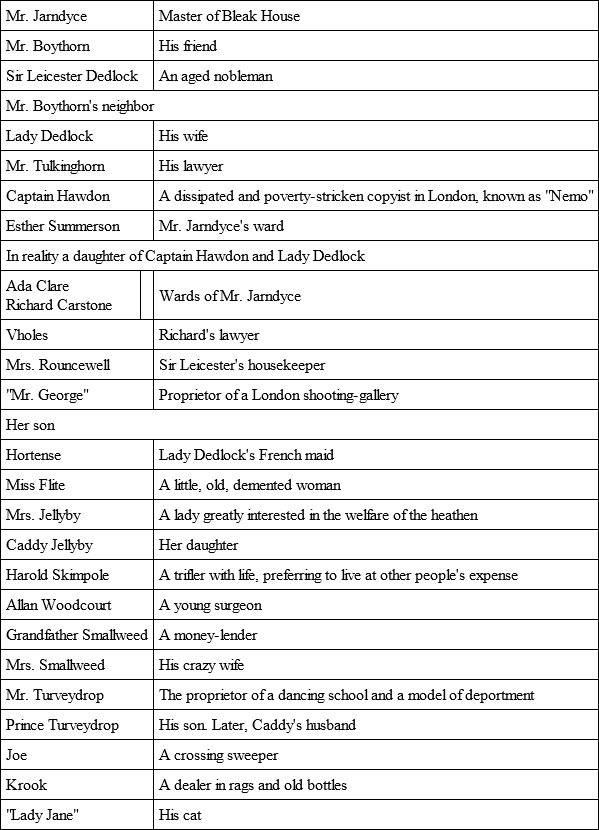

BLEAK HOUSE

BLEAK HOUSE

I

THE COURT OF CHANCERY

An Englishman named Jarndyce, once upon a time having made a great fortune, died and left a great will. The persons appointed to carry out its provisions could not agree; they fell to disputing among themselves and went to law over it.

The court which in England decides such suits is called the Court of Chancery. Its action is slow and its delays many, so that men generally consider it a huge misfortune to be obliged to have anything to do with it. Sometimes it has kept cases undecided for many years, till the heirs concerned were dead and gone; and often when the decision came at last there was no money left to be divided, because it had all been eaten up by the costs of the suit. Lawyers inherited some cases from their fathers, who themselves had made a living by them, and many suits had become so twisted that nobody alive could have told at last what they really meant.

Such came to be the case with the Jarndyce will. It had been tried for so many years that the very name had become a joke. Those who began it were long since dead and their heirs either knew nothing of it or had given up hope of its ever being ended.

The only one who seemed to be interested in it was a little old woman named Miss Flite, whom delay and despair in a suit of her own had made half crazy. For many years she had attended the Chancery Court every day and many thoughtless people made fun of her.

She was wretchedly poor and lived in a small room over a rag-and-bottle shop kept by a man named Krook. Here she had a great number of birds in little cages – larks and linnets and goldfinches. She had given them names to represent the different things which the cruel Chancery Court required to carry on these shameful suits, such as Hope, Youth, Rest, Ashes, Ruin, Despair, Madness, Folly, Words, Plunder and Jargon. She used to say that when the Jarndyce case was decided she would open the cages and let the birds all go.