Полная версия:

Born to Be Posthumous

Reading insatiably, exploring Chicago’s cultural offerings with gusto, Gorey was refining the approach that would make him a species of one as an artist. Consciously or not, he was stuffing the curiosity cabinet of his mind with ideas and images (“I keep thinking, how can I use that?”) that would one day reappear, reimagined, in his art or writing.69

His forays into Chicago’s art scene undoubtedly acquainted him with what would turn out to be another of his great passions, surrealism. At her eponymous gallery, the pioneering dealer and curator Katharine Kuh showed Miró, Man Ray, and the surrealist-influenced Mexican modernist Rufino Tamayo, all in ’38, Gorey’s first year at Parker. Improbably enough, the town that loathed modernism—the Tribune poured scorn on Kuh, and Sanity in Art protested her shows—proved surprisingly congenial to surrealism. The Arts Club, a private sanctum for the city’s moneyed elite whose exhibitions were nonetheless open to the public, introduced Chicagoans to Salvador Dalí in a 1941 show and, in ’42, to André Masson and Max Ernst; Gorey could easily have seen these shows.

Truth be known, though, he never had much use for surrealist art, beyond Ernst’s collage novels and Magritte, who he once claimed was one of his three favorite painters. (Francis Bacon and Balthus were the other two.) Nonetheless, he was profoundly influenced by surrealist ideas. Asked, “Do you view yourself in the Surrealist tradition?” he said, “Yes. That philosophy appeals to me. I mean that is my philosophy if I have one, certainly in the literary way.”70

In his books, he often employs surrealism’s dream logic, as in the non sequitur causality of The Object-Lesson, in which an umbrella disengages itself “from the shrubbery, causing those nearby to recollect the miseries of childhood” and it becomes apparent, “despite the lack of library paste,” that something has happened to the vicar. Sometimes he makes use of Magritte’s hallucinatory conjunctions, as in The Prune People, in which prim, proper Edwardians with prunes for heads go matter-of-factly about their affairs. Or he imagines the inner lives of objects—a very surrealist thing to do—as in Les Passementeries Horribles, in which hapless Edwardians are menaced by ornamental tassels grown to monstrous size.

But even when he isn’t drawing on surrealism so obviously, his stories are often thick with that atmosphere of somnambulistic strangeness that is a surrealist trademark, as in the eerie, wordless The West Wing, a procession of frozen moments set in the usual Victorian-Edwardian mansion, in the usual crepuscular gloom, where everything—the enigmatic package tightly tied with twine in one room, the wave-ruffled water rising halfway up the walls in another, the nude man standing with his back to us on a balcony—manages to seem simultaneously like a clue in an Agatha Christie mystery and a symbol from Magritte’s The Key to Dreams.

Gorey was a surrealist’s surrealist: he understood that surrealism wasn’t just the bourgeoisie’s idea of dream imagery—limp watches, lobster telephones, the guy with the floating apple obscuring his face. It was meant to be an applied philosophy—a way of looking at everyday life, a way of being in the world. “What appeals to me most is an idea expressed by [the surrealist poet Paul] Éluard,” said Gorey. “He has a line about there being another world, but it’s in this one. And [the surrealist turned experimental novelist] Raymond Queneau said the world is not what it seems—but it isn’t anything else, either. Those two ideas are the bedrock of my approach.”71

He even went so far as to suggest that life, with its random juxtapositions and meaningless events, could be seen as a surrealist collage. “I tend to think life is pastiche,” he said, adding drolly, “I’m not sure what it’s a pastiche of—we haven’t found out yet.”

It was surrealism that led Gorey to what would become an overmastering passion: the ballet. In January of 1940, “I went off by myself to see the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo do Bacchanale,” he recalled, “because of its sets and costumes designed by Salvador Dalí, who had been sprung on me by Life magazine.”72 (At the age of fourteen, Gorey thought Dalí “was the cat’s ass.”)73

Bacchanale, unfortunately, was a letdown. But if Ted wasn’t swooning over Dalí’s decor—the dancers emerged from a ragged hole in the breast of the gargantuan swan in the backdrop—or his strenuously outrageous costumes (one dancer wore a fish head), he was bowled over by the ballerina who danced the role of Lola Montez in “enormous gold lamé bloomers encircled at their widest part by two rows of white teeth,” an appropriately surrealist getup that was the handiwork of the renowned costume maker Karinska.74 Gorey was entranced by Karinska’s creations; fifty-five years later, in his foreword to Costumes by Karinska, a book about her work, he rhapsodized about costumes “I have fondly remembered, some for over half a century,” such as “the satin and ruffled dresses for the cancan dancers in Gaîté Parisienne, whose combinations of colors I still think were the most gorgeous I ever saw.”75

As well, he liked Matisse’s brightly colored sets and abstract-patterned costumes for another ballet on the program, Rouge et Noir. As knots of dancers “formed and came apart” against the backdrop, a critic wrote, they created “wonderful blocks of color like an abstract painting set in motion.”76

Already Gorey’s omnivorous eye was drawn to set design, which he would dabble in for much of his artistic life, and to costumes, a fascination evident in the attention he lavished on his characters’ dress, poring over Dover books such as Everyday Fashions of the Twenties and Victorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper’s Bazaar to ensure they were period-perfect. In a sense, Gorey lived out his Karinska fantasy in his books, playing costumier to the casts of his stories (and, later, to the actors in his theatrical entertainments). On the page, where his imagination was unbounded by budget or tailoring skills, he conjured up outfits so dazzling they beg for the stage or the fashion runway.

His appetite whetted, he began going to the ballet off and on, though he wouldn’t become the obsessive balletomane we know until his conversion, sometime in the early ’50s, to the cult of Balanchine and the New York City Ballet (whose principal costumier, from 1963 to ’77, was Karinska).

By his senior year at Parker, Gorey had matured from a kid who liked to draw into the budding artist who would bloom at Harvard. Along with Mitchell and her friend Lucia Hathaway, he juried the school’s Annual Exhibit of Students’ Work (a more heroic undertaking than it sounds, since the show included 856 pieces of art, 22 of which were Gorey’s). He did the sets and costumes for the senior play and, as a member of the social committee, handled the posters and decorations for extracurricular events. Somehow he found time, on top of all this, to art-direct the 1942 yearbook.

Yet despite this whirlwind of artistic activity, Gorey was far from an eccentric loner, hunched over his drawing board on prom night. “Though a newcomer to Joan’s Class of ’42, Ted had claimed a central position in that class, owing to a jaunty individualism,” Patricia Albers asserts.77 What made Gorey stand out, Robert McCormick Adams recalls, was “a conscious point of view that was not so much critical as it was independent, and somehow coherent.” Central to that perspective was a wryly detached take on human affairs. “He was always putting his finger on ironies or absurdities,” says Adams. His wit and easygoing self-assurance won him invitations to parties and dances at places with names like the Columbia Yacht Club, and he was part of the gang that hung out at the Belden, a drugstore just down Clark Street where Parkerites yakked and swigged chocolate Cokes and showed off their newly acquired vice, smoking.

Yet among the class photos in the 1942 yearbook, we find a blank spot on the page where Gorey’s thumbnail should be. Apparently he managed (accidentally on purpose?) to miss picture day. Alongside his name is the obligatory jokey biography, which in this case is surprisingly prescient: “Brilliant student … Art addict … Romanticist … Little men in raccoon coats.”

The seventeen-year-old Ted who graduated from Parker on June 5, 1942, was more than just an art addict who doodled little men in raccoon coats. He’d already settled on a career in the arts, though he was sufficiently a child of the Depression to hedge his bohemianism with pragmatism, betting that commercial illustration was more likely to fatten his wallet than art for art’s sake. To that end, he’d taken several courses in commercial art and cartooning at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago while still at Parker and had spent two summers, and a few terms’ worth of Saturday sessions, studying at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. (Walt Disney was its most famous alum.)

Yet despite such preparations, Gorey set his sights not on art school but on Harvard. When asked, on the application, what he expected to get out of Harvard, he said, “I expect to get a good Fine Arts education so that I may enter the field of Fine Art or more probably, use it as a basis for entering the field of Commercial Art.”78

The “historical and cultural advantages in Boston” were a draw, too, he noted. “I have lived all of my life in the Middle West and after I graduated from eighth grade I took a trip East,” wrote Gorey. “I like New England better than any place I have ever been.”79 It’s no surprise that Gorey felt right at home amid the death’s heads grinning from the gravestones in Cambridge’s Old Burying Ground, the crypts and obelisks in Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery, and the brooding Victorians of Boston’s Back Bay, whose windows reminded Henry James of “candid inevitable eyes” watching each other “for revelations, indiscretions … or explosive breakages of the pane from within.”80

Herbert W. Smith, Parker’s principal, recommended Ted for the Harvard College National Scholarship. In his letter to the college, Smith judges him “a boy of real brilliance,” “highly gifted in art,” a front-runner “in any academic subjects in which swift reading and quick comprehension bring success,” though he tempers his praise with the observation that Gorey’s gifts can sometimes get the better of him: “He is the swiftest reader but not the most reflective,” says Smith, and “sometimes sacrifices accuracy to speed.” Still, there’s no denying his raw IQ: “He scores highest on such tests as the American Council of Psychological Examinations (100th percentile year after year).”81

Fascinatingly, the Harvard form includes a question about the applicant’s limitations (“physical, social, mental”), to which Smith replies that Gorey, as “the only child of a highly intelligent but divorced couple,” is prey to “social and financial insecurity.” He’s plagued, too, by occasional migraine headaches, an affliction that will bother him, on and off, for the rest of his life. These minor defects duly noted, Smith recommends him unreservedly; he is “an original and independent thinker” whose “boundless ambition and the direction of his development, quite as much as his high initial ability, make a career of unusual distinction seem likely.” Gorey was awarded a scholarship to Harvard.*

He was accepted by Harvard in May, but with the draft hanging over his head—America was at war, and Congress was considering lowering the age of eligibility from twenty-one to eighteen—he decided to postpone his matriculation. As his mother later explained in a letter to the Harvard Committee on Admission, “By fall we knew that the chances of going through college before he would be in the Army were very slight, and he decided to attend the Art Institute for the fall term until Congress should decide about drafting the 18 year old boys.”82 That November, Congress approved the lowering of the age of eligibility to eighteen; on December 5, FDR signed that decision into law. “When that was decided,” Helen wrote, “we felt that it would be wise for him to enter the University of Chicago, where he had also been awarded a scholarship, as there was just a chance that he might be able to get a year’s credit under the accelerated program.” Gorey began classes at U of C in February of 1943, the month he would turn eighteen.

Four months into his studies, his number came up in the national lottery run by the Selective Service. On May 27, Gorey was inducted into the US Army at Camp Grant, near Rockford, Illinois. In June, he was sent to Camp Roberts, in central California, just north of San Miguel, for four months of basic training. IQ tests were part of the induction process, and as Helen Gorey—never one to hide her son’s light under a bushel—recalled, “His grade in the Army intelligence test was 157, which was the highest mark they had ever had at Camp Grant at that time.”83 On completing his basic training, he underwent another round of examinations, after which he learned from the Board of Examiners, according to Helen, “that he had the highest marks they had seen.”

Army life, Gorey wrote to his friend and former Parker schoolmate Bea Rosen, was dull to the point of deadliness.84 At one point, he and his company were marched out into the wastelands around Camp Roberts and bivouacked there, God knows why, a state of affairs Gorey found “too, too feeble-making.”85 He and his fellow grunts were sleeping on brick-hard ground, he told Rosen, and subsisting on canned rations eaten cold. Dessert consisted of chocolate bars that tasted suspiciously like Ex-Lax and had “practically the same effect, if not more so.” His mood was not improved when he managed to drop a rifle on his foot. The army routine alternated between torment and tedium; that, along with the infernal heat and lunar desolation of the place, was driving him out of his gourd, he claimed.

Gorey’s voice on the page is something to hear, as far from the average GI writing home as Oscar Wilde’s arch quips are from Hemingway’s tough-guy bluster. He opens his letters to Rosen with stage-entrance salutations like “Darling,” closes them with high-flown effusions (“tidal waves of passion” is a typical sign-off), and adopts pet names (he’s “Theo”; Rosen is “Beatrix the light of my life”). He affects a knowingness, a world-weariness; he indulges in high-opera histrionics and flights of fancy. It’s the put-on persona of a teenage aesthete who has lived much of his young life between the covers of a book. Life, he insists, is a tear-sodden handkerchief, a crumpled straw in a soda glass sucked dry, a foot-draggingly gloomy procession of “frustrated desires” and “sex entanglements from what they tell me—I wouldn’t know … ”86 (Interesting to note that at eighteen—an age when most young men are feeling their oats—he’s already holding the subject of “sex entanglements” at arm’s length.)

Gorey’s letters are a study in camp. His tone is equal parts Sebastian Flyte, the charmingly unworldly idler from Brideshead Revisited, and the impulsive, outspoken Holly Golightly from Breakfast at Tiffany’s, down to Holly’s precious use of French to signal her cosmopolitan chic. In a letter to Rosen, Gorey sighs, “The ancient esprit d’aventure still lives but what can it do?”87

Gorey’s summer in “God’s garbage pit,” as he called it, wasn’t all cold canned rations and damp rot of the soul. Rummaging through the camp library in his never-ending search for something new to read, he happened on E. F. Benson’s Mapp and Lucia novels. “I first discovered them during World War II—quite by accident, although I prefer to think of it as Fate—in the library of Camp Roberts, California, where I took my basic training in the summer of 1943,” he remembered in “I Love Lucia,” an appreciation he wrote for the May 1986 issue of Vogue.88

Fate indeed: Benson’s comedies of manners arrived at just the right moment to influence Gorey’s emerging persona, that of an arch, Anglophilic aesthete. Wickedly witty and unimprovably English in their attention to small-town gossip and social jockeying, the Mapp and Lucia novels delight in the snobbery and pretensions of two smilingly vicious doyennes who elevate social climbing to a blood sport. As it happens, Benson (1867–1940) was gay, and the Mapp and Lucia novels are “cult classics … among gay readers,” according to the literary critic David Leon Higdon, beloved for “their campy exaggerations, social jealousies, and gentle but not altogether affectionate social satire.”89 Was Gorey drawn to Benson’s novels because he recognized in Benson’s voice a kindred style of mind, a covert consciousness that wore its wit as an invisibility cloak?

Whatever the reason, the books made a lasting impression on him: when asked about his favorite authors, he often mentioned Benson. “If I were driven to decide what to take along to a desert island,” he said in 1978, “it would be a toss-up among Jane Austen’s complete works, [the eleventh-century Japanese novel] The Tale of Genji, the ‘Lucia’ books, or one of the Trollope series,” adding, “I’ve read the ‘Lucia’ books so often I almost know them by heart.”90

Four months after his arrival at Camp Roberts, Gorey completed his basic training, in the course of which he, the overwrought aesthete, last seen dropping his rifle on his foot, managed to earn expert badges in pistol and rifle marksmanship.

Then the army had new marching orders for Private Gorey: he was to enroll in college under the auspices of the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). “Note well the utterly hysterical fact that the Army is sending me to college to study languages under ASTP,” he wrote Rosen.91 Launched in 1943, the ASTP was intended “to provide the continuous and accelerated flow of high grade technicians and specialists needed by the Army.”92 Soldiers who scored high on military IQ tests were sent to select universities—in uniform, on active duty, and still subject to military discipline—for fast-tracked courses in engineering, medicine, and any of thirty-four foreign languages. Gorey was assigned to study Japanese, perhaps in advance of the anticipated occupation of Japan, where US administrators would be needed.

He entered the University of Chicago in the winter quarter of 1943. On November 8, he began courses. Two days later, he was diagnosed with scarlet fever and hospitalized for six weeks. Back on his feet, he reentered the program and was transferred, on February 7, 1944, to something called Curriculum 71, which entailed studying conversational Japanese along with contemporary history and geography. Then, on March 22, the army, with its usual sagacity, shut down the program in mid-term, around five weeks before it would have ended. By Gorey’s tally, he’d had “only two months” of study.93

In June, or thereabouts, the army, again demonstrating the discernment for which it is universally admired, put PFC Gorey’s record-breaking IQ to good use: he was dispatched to Dugway Proving Ground, an army base in the Great Salt Lake Desert, to sit out the rest of the war as a company clerk.

* After Skeezix, the foundling left on a doorstep in the long-running newspaper strip Gasoline Alley.

* According to Elizabeth M. Tamny in an unedited early draft of her November 10, 2005, Chicago Reader feature, “What’s Gorey’s Story? The Formative Years of a Very Peculiar Man,” Gorey was awarded scholarships to the University of Chicago and Carnegie Mellon as well. Reportedly his was the highest score in the Midwest the year he took the college boards. Tamny cites her phone interview with Andreas Brown as the source of these details.

CHAPTER 2

MAUVE SUNSETS

Dugway, 1944–46

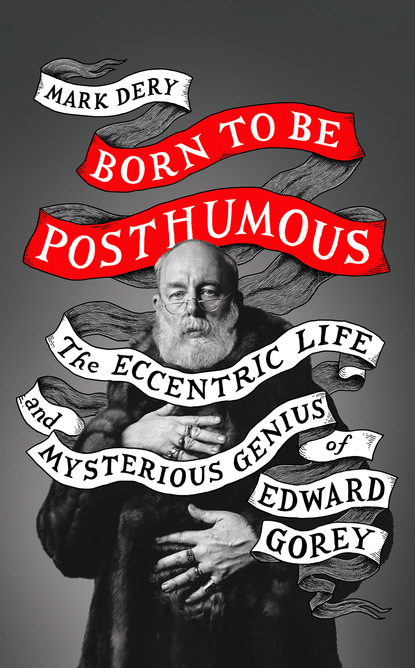

Private Gorey, US Army, circa 1943. (Elizabeth Morton, private collection)

Dugway sits about seventy-five miles southwest of Salt Lake City in a no-man’s-land the size of Rhode Island. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, the army had gone looking for a suitably godforsaken patch of land where its Chemical Warfare Service could test chemical, biological, and incendiary weapons. It found it in Dugway Valley, as far from human habitation as any place in the Lower Forty-Eight and cordoned off by mountain ranges, helpful in shielding top-secret experiments from prying eyes.

Dugway Proving Ground was “activated”—officially opened—on March 1, 1942; when Gorey arrived, a little more than two years later, it still had a ramshackle, frontier feel. The high-security areas devoted to top-secret research and testing would’ve been off-limits to Gorey, restricting him to a cluster of buildings about the size of a large city block, maybe two blocks at best.

All around lay wastelands: salt flats, sand dunes, and, from the base to the jagged mountains rearing up to the north and south, the never-ending desert, tufted with saltbush and sagebrush. The stillness was profound, a ringing in the mind. The sky was painfully clear, by day a vaulted blue vastness, at night a black dome powdered with stars.

Not for nothing was the base’s mimeographed newspaper called The Sandblast. “Dust from the local sand dunes, augmented by ancient lake-bed deposits (Lake Bonneville) and volcanic ash beds, pervaded everything each time the wind blew, which was most of the time,” a former Dugwayite recalled.1 New arrivals were greeted with the cheerful salutation, scrawled on the MP gatehouse, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here,” until top brass caught wind of the offending phrase and ordered it removed.2

Gorey was not enamored of Dugway. “It was a ghastly place, with the desert looming in every direction, so we kept ourselves sloshed on tequila, which wasn’t rationed,” he recalled in 1984. “The only thing the Army did for me was delay my going to college until I was twenty-one, and that I am grateful for.”3 His daily routine, as company clerk—technician fourth grade in the 9770th Technical Service Unit, in armyspeak—didn’t exactly challenge Camp Grant’s all-time high scorer on the army IQ test. He typed military correspondence, sorted mail, and kept the company’s books. “There was this one company: it had all of three people,” he remembered. “One man was in jail, one was in the hospital and one was AWOL for the entire time I was there. But every morning I had to type out this idiot report on the company’s progress.”4

It seems not to have occurred to Gorey, at the time, that swilling tequila and filing absurdist reports was preferable to crawling on your belly through the malarial swamps of some Pacific atoll under withering fire from the Japanese or rotting in a German POW camp. You had hot chow, cold beer—hell, even a bowling alley—and weekend passes to Salt Lake City. Best of all, your chances of dying were next to nil.

Of course, Ted had to grouse. His image, well defined by the time he arrived at Dugway, required that he do his best impression of Algernon Moncrieff from The Importance of Being Earnest, distraught at the impossibility of finding cucumber sandwiches in the middle of the desert. There’s no way of knowing how much of his horror was genuine and how much of it was part of a studied pose.

Gorey’s time at Dugway wasn’t all lugubrious attitudinizing. Relief arrived in the form of a dark-haired, bespectacled Spokane native named Bill Brandt. A gifted pianist and aspiring composer, Brandt was Dug-way’s librarian of classified materials, an assignment that freed him, on weekends, to work on his composing and counterpoint studies. (He would go on to a distinguished career as a professor of music at Washington State University.) “Bill was assigned to the Chemical Warfare Division and Gorey was assigned as company clerk,” Brandt’s wife, Jan, recalled. “Bill had to go to him to order supplies and one day found him reading an avant-garde book. Bill said, ‘Oh! You’re reading one of my favorite books.’ A conversation started and they found they had many interests in common.”5

Five years younger than Brandt, Gorey impressed the older man “as a spare, gawky … boy who played with words,” Jan remembers. Brandt, too, had a quick wit and a knack for wordplay—specifically, puns. Brandt’s own recollection, in an unpublished memoir, of his first encounter with the “new company clerk” portrays Gorey as “a slim, blond man, younger than I, who, I discovered, was literate, in contrast to the professional chemists or old Army types that made up the rest of the outfit. He had actually read the poetry of T. S. Eliot, and Somerset Maugham’s novels!”6