Полная версия:

Born to Be Posthumous

According to Gorey, “the Victorian and Edwardian aspect” of his work had its origins in “all those 19th-century novels I’ve read and [in] 19th-century wood engraving and illustration.”9 But there was a more elusive quality that seduced him as well, “the strange overtone” nineteenth-century illustrations have taken on over time.10 The Victorian era bore witness to the birth of the mass media, inundating British society with a flood of mass-produced images. Many of those images are still floating around, in one form or another, and Gorey was drawn to the uncanniness of all those transmissions from a dead world—specifically, to their unsettling combination of coziness and creepiness, which Freud called the unheimlich (literally, “unhomelike”).

It was that same quality, he thought, that seduced the surrealist artist Max Ernst, who with the aid of scissors and paste conjured up dreamlike vignettes from Victorian and Edwardian scientific journals, natural-history magazines, mail-order catalogs, and pulp literature. Gorey was profoundly influenced by Ernst’s wordless, plotless “collage novels,” of which Une Semaine de Bonté (A week of kindness, 1934) is the best known. Seamlessly assembled from black-and-white engravings, Ernst’s images look like scenes from silent movies shot on some back lot of the unconscious: a bat-winged woman weeps on a divan, oblivious to the sea monster beside her; a tiger-headed man brandishes a severed head, fresh from the guillotine. “I was very much taken with [nineteenth-century illustrations], in the same way that I presume Max Ernst was,” said Gorey. “I mean, all those things that Ernst used in his collages can’t have looked that sinister to people in the 19th century who were just leafing through ladies’ magazines and catalogues. And, of course, now they look nothing but sinister, no matter what. Even the most innocuous Christmas annual is filled with the most lugubrious, sinister engravings.”11

Gorey started drawing even earlier than he started reading, at the age of one and a half.12 “My first drawing was of the trains that used to pass by my grandparents’ house,” he remembered.13 Benjamin St. John Garvey and Prue (as Ted’s stepgrandmother, Helen Greene Garvey, was known to the family) lived in Winthrop Harbor, an affluent suburb north of Chicago on the shores of Lake Michigan. Their house was on a bluff, overlooking the Chicago and North Western railroad tracks. Describing his infant effort, he recalled, “The composition was of various sausage shapes. There was a sausage for the railway car, sausages for the wheels, and little sausages for the windows.”14

Gorey, who saw much more of his mother’s side of the family than he did his father’s, seems to have had fond memories of his visits to Winthrop Harbor: family photos show him squatting by an ornamental pond, peering at a flotilla of lily pads; trotting alongside his grandfather as he mows the lawn.

All of which has the makings of what Gorey assured interviewers was a disappointingly “typical sort of Middle-Western childhood.”15 Before his birth, however, his grandparents starred in a gothic set piece—a messy divorce—that must have scandalized the Garvey clan, especially since the Chicago papers gave it front-page play. (Benjamin was vice president of the Illinois Bell Telephone Company, and his marital melodrama made good copy.) Whether any sense of things hushed up crept into the corners of Gorey’s consciousness, we don’t know, though it’s tempting to locate the sense of things repressed that pervades his work—the furtive glances, the averted gazes—in the grown-ups’ whisperings about scenes played out behind closed doors.

Gorey’s grandmother Mary Ellis Blocksom Garvey had divorced his grandfather in 1915; it was the unhappy denouement of a marriage buffeted by accusations of madness and counteraccusations of forced stays in sanitariums, where Gorey’s grandmother was restrained in a strait-jacket and left to languish in solitary confinement, she claimed. “tried to drive me insane,” wife asserts in suit, the Chicago Examiner blared. phone man kept her in sanitarium until reason fled, she declares.16

The divorce sowed discord among the Garvey children. Ted’s cousin Elizabeth Morton (known by her nickname Skee*) remembers him talking about his mother and her siblings fighting. Skee’s sister, Eleanor Garvey, thinks “it was a fairly volatile family.”

Asked by an interviewer if he was an only child, Gorey said, “Yes. And in childhood I loved reading 19th-century novels in which the families had 12 kids.”17 Then, in the next breath: “I think it’s just as well, though, that I didn’t have any brothers or sisters. I saw in my own family that my mother and her two brothers and two sisters were always fighting. There were so many ambivalent feelings. And then my grandmother would go insane and disappear for long periods of time.” (Madness and madhouses recur throughout Gorey’s work: an asylum broods on a desolate hill in The Object-Lesson; the protagonists of The Willowdale Handcar spy a mysterious personage who may or may not be the missing Nellie Flim “walking in the grounds of the Weedhaven Laughing Academy”; Madame Trepidovska, the ballet teacher in The Gilded Bat, loses her reason and “must be removed to a private lunatic asylum”; Jasper Ankle, the unhinged opera fan who stalks Madame Caviglia in The Blue Aspic, is “committed to an asylum where no gramophone [is] available”; Miss D. Awdrey-Gore, the reclusive mystery writer memorialized in The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, may or may not have gone to ground in “a private lunatic asylum”; and on and on.)

In later life, Gorey adopted Eleanor and Skee as surrogate siblings. “I felt as if I were his little sister,” says Skee. “Since we never had a brother, and he never had any siblings …” She trails off, the depth of feeling in her voice unmistakable. “I think that’s why he liked being here, ’cause it was like having sisters,” she decides. (By “here,” she means Cape Cod, where Gorey spent summers with his Garvey cousins from 1948 on, moving there for good in 1983.) Cousins are the most frequent familial relations in Gorey’s stories; make of that what you will.

The childhood Gorey insisted was “happier than I imagine” was troubled by tensions in his parents’ marriage, too. Class frictions between the Garveys’ aspirational WASPiness and the Goreys’ cloth-cap Irishness complicated things. Who knows how Ted negotiated the transition from his well-heeled grandparents’ suburban idyll, in Winthrop Harbor, to the corner-pub world of his Gorey relatives?

Unsurprisingly, the group psychology of families—relations between husbands and wives, the interactions of parents and children—is fraught in Goreyland. Parents are absent or hilariously absentminded, like Drusilla’s parents in The Remembered Visit, who, “for some reason or other, went on an excursion without her” one morning and never returned. Of course, neglectful parents are vastly preferable to the heartless type, a more plentiful species in Gorey stories. In The Listing Attic, we meet the “headstrong young woman in Ealing” who “threw her two weeks’ old child at the ceiling … to be rid of a strange, overpowering feeling”; the Duke of Daguerrodargue, who orders the servants to dispose of the puny pink newborn that nearly killed his wife in child-birth; and the “Edwardian father named Udgeon, / whose offspring provoked him to dudgeon,” so much so that he’d “chase them around with a bludgeon.”

Kids growing up in households where adults are inscrutable and unpredictable learn that keeping their mouths shut and their expressions blank is the shortest route to self-preservation. (Burying your nose in a book is another way of making yourself invisible.) Gorey’s people are almost entirely expressionless, their mouths tight-lipped little dashes; they barely make eye contact and shrink from displays of affection. Conversation consists mostly of non sequiturs; awkward silences hang in the air. Alienation and flattened affect are the norm.

The only truly happy relationships in Gorey’s books are between people and animals: Emblus Fingby and his feathered friend in The Osbick Bird, Hamish and his lions in The Lost Lions, Mr. and Mrs. Fibley and the dog they regard as a surrogate child when their infant disappears from her cradle in The Retrieved Locket. None of which is at all surprising: Gorey’s fondness for his cats was at least as deep as his affection for his closest human friends, probably deeper. Asked by Vanity Fair, “What or who is the greatest love of your life?” he replied, “Cats.”18 Perhaps the warmest bonds are between animals, as in The Bug Book, the only Gorey title with an unequivocally happy ending. In it, a pair of blue bugs who live in a teacup with a chip in the rim are “on the friendliest possible terms” with some red bugs and yellow bugs, calling on each other constantly and throwing delightful parties. They’re all cousins, of course.

In 1931, another not entirely ordinary incident ruffled the placid surface of Gorey’s “perfectly ordinary” childhood. He was six, but his precociousness enabled him to skip first grade and enroll as a second grader. The school in question was a parochial school; Gorey had been baptized Catholic. Saint Whatever-It-Was (no one knows which of Chicago’s parochial schools he attended) was loathe at first sight. “I hated going to church and I do remember I threw up once in church,” he recalled. “I didn’t make my First Communion because I got chicken pox or measles or something and that sort of ended my bout with the Catholic church.”19

The temptation to see Gorey’s suspiciously well-timed illness as a verdict on the faith is tempting, especially in light of his terse response to the question, “Are you a religious man?”: “No.”20 His brief spell in Catholic school didn’t leave him with the usual psychological stigmata, he claimed—“I’m not a ‘lapsed Catholic’ like so many people I know who apparently were influenced forever by it”—but it does seem to have put him off organized religion for good.21

A subtle anticlerical strain runs through Gorey’s work: cocaine-addled curates beat children to death, nuns are possessed by demons, unfortunate things happen to vicars. In Goreyland, immoderate religiosity is soundly punished: Little Henry Clump, the “pious infant” of Gorey’s 1966 book of the same name, is pelted by giant hailstones, succumbs to a fatal cold, and lies moldering in his grave, all of which make the narrator’s assurance that Henry has gone to his reward sound like a laugh line for atheists. Saint Melissa the Mottled, a book Gorey wrote in 1949 but never got around to illustrating (Bloomsbury published it posthumously, with images filched from his other books), is a gothic hagiography about a nun noted not for good works but for Miracles of Destruction. Given to dark designs involving blowgun darts, Melissa graduates, in time, to “supernatural triflings” such as the withering of the Duke of Dimgreen’s arm and a seagull attack on two young girls. In death, she becomes the patron saint of ruinous randomness. She’s just the sort of saint you’d dream up if you believed, as Gorey did, that “life is intrinsically, well, boring and dangerous at the same time. At any given moment the floor may open up. Of course, it almost never does; that’s what makes it so boring.”22

In fact, the floor was always opening up in Gorey’s early years.

For example, after his less-than-successful year in parochial school, his parents sent him to Bradenton, Florida, a small city between Tampa and Sarasota, to live with his Garvey grandparents for the following year.

Why? It is, as they say in Catholic theology, a Mystery.

In the fall of ’32, he entered third grade in Bradenton, at Ballard Elementary. He seems to have landed on his feet, catlike, in alien surroundings: he made new friends, had a dog named Mits, was a devoted reader of the newspaper strips (“I get all the Sunday funnies, but I want you to send down the everyday ones,” he wrote his mother), and earned high marks on his schoolwork.23

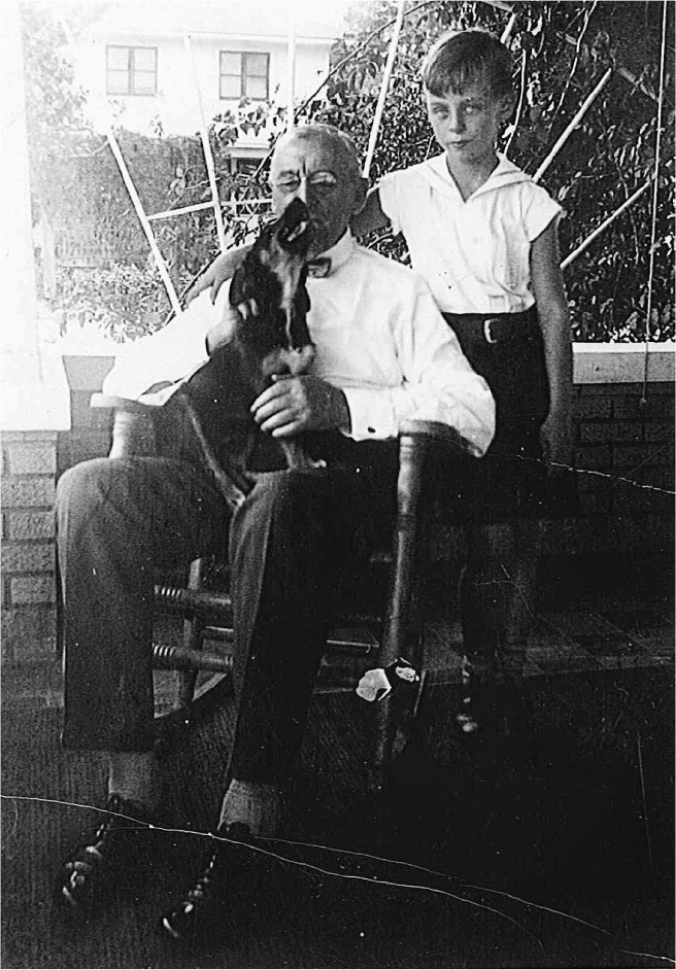

But a December 1932 photo of him with his grandfather Benjamin Garvey tells another story. Sitting in a rocker on what must have been the Garveys’ porch or patio, the old man gazes benignly, through wire-rimmed glasses, at the dog on his lap, petting him; Mits—it must be Mits—arches his back in an excess of contentment. Ted stands behind him, a proprietary hand on his grandfather’s shoulder. He regards us with the same penetrating gaze, the same unsmiling mien we see in his posed photos as an adult. It is, to the best of my knowledge, the only picture of Gorey touching someone in an obvious gesture of affection.

Gorey, age seven, in Bradenton, Florida, with his maternal grandfather, Benjamin S. Garvey, December 1932. (Elizabeth Morton, private collection)

Returning to Chicago in May of ’33, eight-year-old Ted was packed off to something called O-Ki-Hi sleepaway camp, an “awful” experience he managed to survive by spending all his time “on the porch reading the Rover Boys.”24

Clearly there was more than enough unpredictability and inexplicability in his world to inspire his life’s goal, as an artist, of making everybody “as uneasy as possible, because that’s what the world is like.” “We moved around a lot—I’ve never understood why,” he told an interviewer when he was sixty-seven. “We moved around Rogers Park, in Chicago, from one street to another, about every year.”25 By June of 1944, when he left Chicago for his army posting to Dugway Proving Ground, outside Salt Lake City, he’d called at least eleven addresses home: two in Hyde Park, five in Rogers Park, two in the North Shore suburb of Wilmette, one in the city’s Old Town neighborhood (in the Marshall Field Garden Apartments), and one in Chicago’s Lakeview community.26 He’d been bundled off to Florida twice, the second time to Miami, where in 1937 he attended Robert E. Lee Junior High, returning to Chicago for the summer of ’38. All told, he’d gone to five grammar schools by the time he enrolled in high school.

In later years, Gorey would structure his everyday life through unvarying routines, some of them so ritualized they bordered on the obsessive-compulsive. It’s hard not to see them as a response to the rootlessness of his early years—existential anchors designed to tether a self he often experienced as unmoored, disconcertingly “unreal,” given to “drift.” Compulsive in the colloquial if not the clinical sense of the word, Gorey’s daily rituals may have provided a reassuring predictability, and thus a sense of stability, to a man marked by the frequent, never-explained disruptions that kept yanking the rug out from under him during his childhood.

Looking back from the age of seventy, he still couldn’t make sense of his family’s apparently arbitrary movements around the city. “I never quite understood that. I mean, at one point I skipped two grades at grammar school, but I went to five different grammar schools, so I was always changing schools … which I didn’t like. I hated moving and we were always doing it. Sometimes we just moved a block away into another apartment; it was all very weird.”27

In 1933, the Great Depression hung on the mental horizon like a thunderhead, darkening American optimism. It was the year the economy hit rock bottom, with one in four workers out of a job. And then there was the waking nightmare of the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby. A year ago that May, a horrified nation read the news of a truck driver’s accidental discovery of the infant’s badly decomposed body, partly dismembered, his head bashed in. Charles Lindbergh was one of the most famous people in the world; the child’s abduction on March 1, 1932, and the unfolding story of the Lindberghs’ fruitless negotiations with the kidnapper, mesmerized America, as did the manhunt that followed the gruesome discovery of Baby Lindy’s remains.

Ted couldn’t have been oblivious to the crime of the century, as the papers dubbed it. Maybe he followed the unfolding horror story in the Chicago Daily News, as his soon-to-be high school classmate Joan Mitchell did: the baby snatched from his bed in the dead of night; the creepy, barely literate ransom note (“warn you for making anyding public or for notify the Police”).28 Mitchell was sick with fear that bogeymen would spirit her away, too. And not without reason: her family was well-to-do, and Illinois, in the Depression years, was ground zero for kidnappings. Ransom payments from the rich were low-hanging fruit for gangsters, who grabbed more than four hundred victims during 1930 and 1931 alone, more than in any other state in the nation.29 The abductions in Gorey’s little books—Charlotte Sophia carried off by a brute in The Hapless Child, Millicent Frastley snatched up by man-size insects in The Insect God, Eepie Carpetrod lured to her doom by the serial killers in The Loathsome Couple, Alfreda Scumble “abstracted from the veranda by gypsies” in The Haunted Tea-Cosy—may be post-traumatic nightmares reborn as black comedy.

Gorey’s awareness of the horrors of everyday life may have been heightened by his father’s experiences as a crime reporter, too. By the time Ted was born, Ed Gorey was covering politics, but it’s not inconceivable that the younger Gorey overheard his father reminiscing about his days on the police beat, writing stories like the ones Ben Hecht filed at the Chicago Daily Journal—gruesome fare such as the tale of a “Mrs. Ginnis, who ran a nursery for orphans in which she murdered an average of 10 children a year,” and the one about the guy who dispatched his wife, lopped off her head, and “made a tobacco jar of its skull,” as Hecht recalled.30 Then, too, as a newspaperman, Ed Gorey would have been a voracious reader of the dailies; it’s easy to imagine his son riveted by the big black headlines screaming from his father’s morning paper, never mind its lurid front-page photos. Could Ted have acquired his appetite for true crime at the breakfast table? The imperturbable voice in which he narrates his tales of fatal lozenges, deranged cousins, and loathsome couples sounds a lot like a poker-faced parody of police-beat reporting, with its terse, declarative sentences and just-the-facts deadpan.

At the same time, there’s no denying the echoes, in his “Victorian novels all scrunched up,” of nineteenth-century fiction, with its whispered intrigues and buried scandals. His vest-pocket melodramas owe a debt, too, to what were known in Victorian England as penny dreadfuls or shilling shockers—cheap, crudely illustrated booklets featuring serialized treatments of unfolding crime stories. And then there were the detective novels Helen and Ed Gorey read by the bushel. “Both my parents were mystery-story addicts,” Ted remembered, “and I read thousands of them myself.”31 Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Margery Allingham, and Dorothy L. Sayers left their imprint on Gorey’s imagination—Christie’s books especially, with their characteristically English blend of snug domesticity and penny-dreadful horrors. “Sinister-slash-cozy,” Gorey called it.32

Christie became the infatuation of a lifetime, and her take on the tea-cozy macabre is a pervasive influence. Gorey’s devotion to the Queen of Crime was absolute, impervious to the passage of time and undeterred by snobbish eye rolling. “Agatha Christie is still my favorite author in all the world,” he said when he was pushing sixty.33 By the time he’d reached seventy-three, he’d read every one of her books “about five times,” he reckoned.34 Her death left him desolate: “I thought: I can’t go on.”35

On top of all that, he grew up in Prohibition-era Chicago—Murder City, in newsroom patois. For much of Gorey’s childhood, Al Capone and his adversaries made the mental life of Chicagoans look like one of those spinning-headline montages in period movies. The horror of bloodbaths like the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre, in which hit men lined gangsters up against a garage wall and raked them with machine-gun fire, reverberated in the mass imagination.

Given the time and place he grew up in, and his father’s days on the police beat, it’s hardly surprising that Gorey, asked why “stark violence and horror and terror were the uncompromising focus of his work,” replied, “I write about everyday life.”36

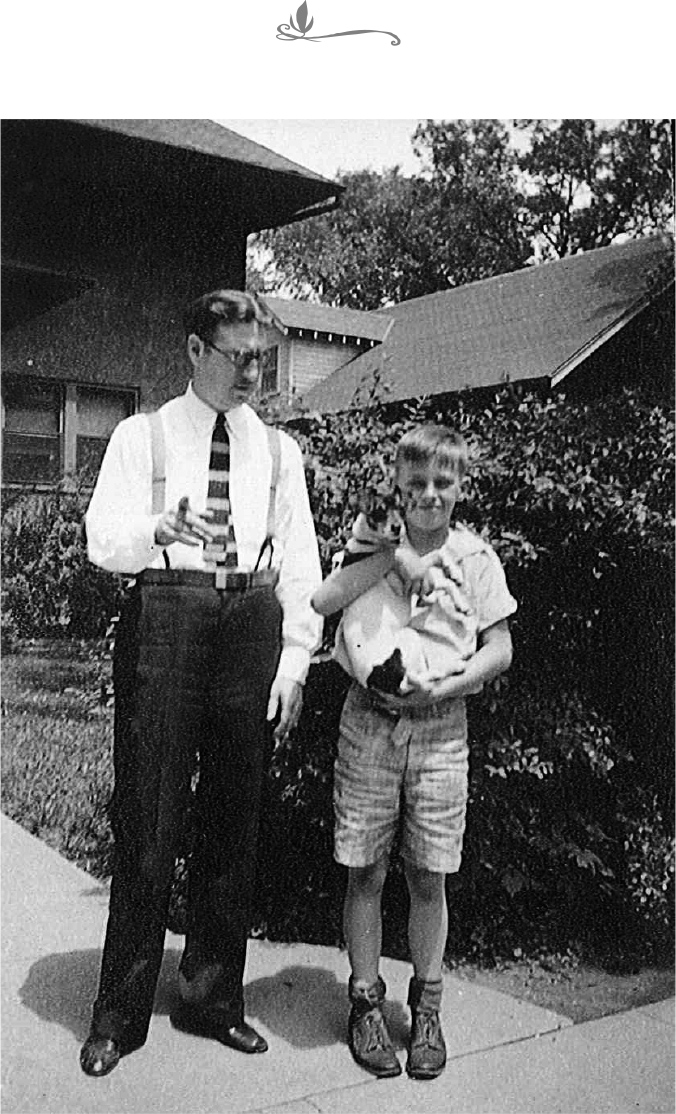

Ted with his father, Edward Leo Gorey, in Wilmette, Illinois, circa ’34–36. Gorey is somewhere between nine and eleven.

(Elizabeth Morton, private collection)

Sometime around April 16, 1934, the Goreys moved from 1256 Columbia Avenue, in the North Side neighborhood of Rogers Park, to the snug, tree-shaded North Shore suburb of Wilmette. (Little is known about Ted’s time on Columbia Avenue beyond the fact that he spent fourth grade at Joyce Kilmer Elementary School, a short walk from the Goreys’ red-brick apartment building, and that he received straight Es—for “excellent”—on his progress report.)37

This change of address was weirder than most, since his father had just landed a new job, not in Wilmette but in downtown Chicago. In 1933, he’d reinvented himself as publicity director of two luxury hotels, the Drake and the Blackstone. Both were bywords for elegance, playing host to champagne-by-the-jeroboam high rollers, backroom deal makers, and even presidents. Why Gorey’s father moved his family farther from his workplace, to the suburbs north of the city, is a puzzler.

Maybe he wanted a better life for his family, a piece of the gracious living advertised by North Shore realtors. The Goreys’ rental was “a cube shaped elephant grey stucco house” at 1506 Washington Avenue in West Wilmette, with “an upstairs sunroom that managed to have windows on all four sides,” as Ted recalled it.38 In the fall of ’34, he enrolled in the sixth grade at Arthur H. Howard School, a cross between an elementary and a junior high school that spanned kindergarten through eighth grade. He was nine years old. How he managed the trick of skipping fifth grade we don’t know; presumably, he tested out of it. As in Bradenton, Ted fit right in. “He does very superior work … with apparent ease, and socially he is well adjusted,” his homeroom teacher, Viola Therman, noted on his spring ’35 report card.39 She was, she wrote, “anxious to see what he will accomplish with an activity program in the form of the puppet play [he is] now planning”—a revealing aside in light of the puppetlike nature of Gorey’s characters and his fascination, near the end of his life, with puppet shows, which he staged in Cape Cod theaters with his hand-puppet troupe, Le Théâtricule Stoïque.

As of June ’36, the Goreys had moved across town to the Linden Crest apartments at 506 5th Street, a block from the 4th and Linden El stop.

That September, Ted enrolled in the eighth grade at a nearby junior high, the Byron C. Stolp School, a shorter walk from his new address than Howard. Gorey, famously not a joiner as an adult, was the quintessential joiner in junior high: alongside his photo in the 1936–37 edition of the Stolp yearbook, Shadows, he’s listed as assembly president as well as a member of the typing club, the Shakespeare club, the glee club, and, not least, the art club.

Gorey’s art teacher at Stolp was Everett Saunders, a former WPA painter and dedicated mentor to would-be artists. Saunders oversaw the art club, whose ranks included Warren MacKenzie and, improbably enough, Charlton Heston. MacKenzie would grow up to be a master potter whose Japanese-influenced clayware is prized for its understated beauty. Now ninety, he remembers Heston as “a real poser,” a characterization confirmed by Heston’s Stolp yearbook photo, in which the man who would be Moses, sporting a budding pompadour, gives the camera an eighth grader’s idea of a smoldering gaze. (What can it mean that “Gorey always claimed with a straight face,” according to his friend Alexander Theroux, that “Charlton Heston was ‘the actor of our time’”?)40

MacKenzie, who coedited the 1937 Shadows, recalls Gorey’s “really funny” cartoons for the yearbook’s club pages. Ted executed nine full-page line drawings, among them a picture of a cat in an artist’s smock and beret holding a palette and a dripping paintbrush (for the art club); a cat in an eyeshade, sweating bullets, up against a deadline from hell (for the journalism club); and a feline Romeo in a Renaissance cape, tearfully pacing his balcony under a crescent moon (for the Shakespeare club). They’re cute in a Joan Walsh Anglund meets Harold and the Purple Crayon way that clashes with our image of what’s Goreyesque.