скачать книгу бесплатно

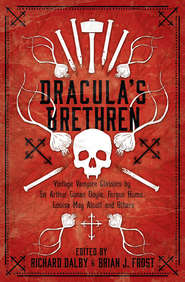

Dracula’s Brethren

Richard Dalby

Brian Frost J.

Neglected vampire classics - including tales by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Louisa May Alcott and others. Selected by Richard Dalby and introduced by Brian J. Frost.In 1897, Bram Stoker’s iconic DRACULA redefined the horror genre and had a significant impact on the image of the vampire in popular culture. But encounters with the undead were nothing new: they had electrified readers of Gothic fiction since even before Victorian times.DRACULA’S BRETHREN is a tribute to those early writers, a collation of 19 archetypal tales written between 1820 and 1910, many long forgotten, celebrating the vampire stories that both inspired and were inspired by Bram Stoker’s iconic novel.A companion to Richard Dalby’s definitive anthology, DRACULA’S BROOD, itself 30 years old, these rediscovered stories are a genuine treasure trove for classic thrill-seekers and all lovers of supernatural fiction.

The frontispiece from the 1820 edition of ‘The Bride of the Isles’.

Copyright (#ulink_c54647ae-2284-5a1f-8a00-35a010ae412c)

HARPER

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Selection, Introduction, and Notes © Richard Dalby and Brian J. Frost 2017

Cover design and illustration by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216481

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008216498

Version: 2017-04-05

Contents

Cover (#u8e801586-4f2a-52a9-a530-18a0a3b2dc5a)

Title Page (#u05a3feb0-c18a-56aa-8659-22ef3a60b91a)

Copyright (#u80f29762-beb3-5fa4-80b1-e5b350bdecb4)

Introduction (#u5adde8f4-6d31-5455-b220-28a30066d79e)

The Bride of the Isles by Anonymous (1820) (#uc8ab0dd0-108b-5f09-9ebd-5c46dc719d77)

The Unholy Compact Abjured by Charles Pigault-Lebrun (1825) (#u0dc2e44c-cd52-585f-8ca3-6b91b9c4d57d)

Viy by Nikolai Gogol (1835) (#u997b085b-b3ae-5b8f-ae78-775ee49c9dba)

The Burgomaster in Bottle by Erckmann-Chatrian (1849) (#litres_trial_promo)

Lost in a Pyramid; or, The Mummy’s Curse by Louisa May Alcott (1869) (#litres_trial_promo)

Professor Brankel’s Secret by Fergus Hume (1882) (#litres_trial_promo)

John Barrington Cowles by Arthur Conan Doyle (1884) (#litres_trial_promo)

Manor by Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1884) (#litres_trial_promo)

Old Aeson by Arthur Quiller-Couch (1890) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Mask by Richard Marsh (1892) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Last of the Vampires by Phil Robinson (1893) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Story of Jella and the Macic by Professor P. Jones (1895) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Ring of Knowledge by William Beer (1896) (#litres_trial_promo)

A Beautiful Vampire by Arabella Kenealy (1896) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Story of Baelbrow by E. & H. Heron (1898) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Purple Terror by Fred M. White (1899) (#litres_trial_promo)

Glámr by Sabine Baring-Gould (1904) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Vampire Nemesis by ‘Dolly’ (1905) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Electric Vampire by F. H. Power (1910) (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Editors (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Editor (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_0dd95f54-ce0e-53ff-a50c-118ce3904587)

ARRANGED chronologically, the nineteen stories in this anthology are culled from books and magazines published between 1820 and 1910, a period noted for producing some of the finest vampire tales ever written. The first vampire story to make a significant impact on European literature was ‘The Vampyre,’ by John William Polidori, which set a precedent by depicting the vampire as an aristocrat. Erroneously attributed to Lord Byron when it was first published in the April 1819 issue of The New Monthly Magazine, this story subsequently inspired a surge of popular interest in vampires and established the vampire’s image as a fatal lover.

In 1820 the French author Cyprien Bérard penned a novel-length sequel to Polidori’s story, titling it Lord Ruthwen ou les Vampires. This, in turn, formed the basis for James R. Planché’s play The Vampire; or, The Bride of the Isles, which had its first performance on the London stage in August 1820. Not long afterwards an anonymously-written short story adapted from the play, bearing the title ‘The Bride of the Isles: A Tale Founded on the Popular Legend of the Vampire,’ was put on sale by an enterprising Dublin publisher. Better than most vampire tales written in the early 1800s, its inclusion in the present volume marks its first appearance in an anthology exclusively devoted to vampire fiction.

The earliest known vampire story by an American writer, Robert C. Sands’ ‘The Black Vampyre: A Legend of Saint Domingo’ (1819), broke new ground by featuring a mulatto vampire. A more significant innovation, the introduction of the female vampire into prose fiction, is the main claim to fame of Ernst Raupach’s ‘Wake Not the Dead,’ which was, for many years, falsely attributed to Johann Ludwig Tieck. A cautionary tale about the folly of bringing the dead back to life, it was originally published in Leipzig in 1822, and received its first English translation a year later when it was included in Popular Tales and Romances of the Northern Nations. Less well-known is the quaintly titled story ‘Pepopukin in Corsica,’ in which a disagreeable suitor is sent packing by inspiring in him a dread of vampires. Originally published in 1827, in The Stanley Tales, Vol. 1, where it was credited to ‘A. Y.’, it was recently claimed that the author these initials belonged to was Arthur Young. Another story from the 1820s, this time by a French writer, is ‘The Unholy Compact Abjured’ (1825), by Charles Pigault-Lebrun, in which a soldier seeking shelter for the night encounters demonic vampires in a spooky chateau.

Russian literature’s first major contribution to the vampire canon was Nikolai Gogol’s ‘Viy,’ which comes from his 1835 collection Mirgorod. Described by Edmund Wilson as ‘one of the most terrific things of its kind ever written,’ it is about a young philosopher’s frightening encounter with a witch-vampire and monstrous winged creatures under the control of the King of the Gnomes. The most famous vampire story from the 1830s is undoubtedly ‘La Morte Amoureuse’ (1836), by the French author Théophile Gautier. Anthologised many times under different titles (e.g. ‘Clarimonde,’ ‘The Dreamland Bride,’ and ‘The Beautiful Dead’), it tells of a young priest’s illicit relationship with a dead courtesan, whose beguiling revenant draws him into a fantastical dreamworld and nightly sucks small quantities of his blood to sustain her life-in-death existence.

Meanwhile, in America, Edgar Allan Poe was turning out a string of morbid horror tales, several of which dealt with unusual forms of vampirism. In ‘Ligeia’ (1838), for instance, he introduced the idea of mental vampirism, linking it with the allied theme of metempsychosis. The ill-fated title character, a beautiful, highly intelligent woman, gradually wastes away as a result of her husband’s obsessive desire to know her completely; but, in a final twist, retribution for this subconscious act of vampirism seems likely when the dead woman’s spirit possesses the body of her marital successor, suggesting that the roles of vampire and victim will shortly be reversed. A variation on the same theme occurs in another of Poe’s stories, ‘The Oval Portrait’ (1845), in which an artist totally absorbed in capturing an absolute likeness of his lovely young bride is unaware of the devitalising effect it is having on her frail constitution, and fails to notice that with each sitting the woman’s life force is ebbing away. Psychic vampirism of an even more bizarre kind is the underlying theme of Poe’s masterpiece, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (1839). In this story the psychic vampire is the ancestral home of the Usher family, and its victims are the current occupants, Roderick Usher and his sister Madeline. By some hideous process, the ancient mansion – a sentient stone organism impregnated with the evil emanations of past generations of Ushers – is having a devitalising effect on the doomed couple, bringing the horror of madness into their lives. These three stories, along with two others utilising the vampire theme, ‘Morella’ (1835) and ‘Berenice’ (1835), were collected together in Dead Brides: Vampire Tales (1999).

A story by one of Poe’s contemporaries, James Kirke Paulding’s ‘The Vroucolacas,’ has, in the past, attracted the curiosity of vampire aficionados due to its extreme rarity, but since it has become accessible on an internet website any hopes that it might turn out to be a forgotten gem have sadly been dashed. Originally published in the June 1846 issue of Graham’s Magazine, it is about a frustrated suitor pretending to be a vampire in order to win the hand of his sweetheart. Vampiric possession is the theme of Erckmann-Chatrian’s ‘The Burgomaster in Bottle,’ which first appeared in the French journal Le Démocrate du Rhin in 1849. Since then, this story has strangely been overlooked by compilers of vampire anthologies, a situation finally rectified by its inclusion within these pages. The most frequently anthologised vampire tale from the 1840s is ‘The Mysterious Stranger,’ the bloodsucking villain of which, Azzo von Klatka, is thought to have been the model for Count Dracula. Formerly uncredited, it has recently been established that the author of this story was a little-known German writer named Karl von Wachsmann, and it first appeared in print in 1844, which is much earlier than was previously supposed. Hereditary vampirism is the theme of Aleksey K. Tolstoy’s ‘Upyr,’ which was first published in 1841 under the pseudonym ‘Krasnorogsky.’ Also worth a brief mention is the vampire episode from Alexandre Dumas’s The Thousand and One Phantoms (1848), which usually bears the title ‘The Pale Lady’ when it is published separately.

Novels with a vampire as the central character were something of a rarity in the first half of the nineteenth century, and the only one remembered today is Varney the Vampyre; or, The Feast of Blood, which was originally published in weekly instalments between 1845 and 1847, coming out in book form immediately afterwards. The vampiric hero-villain of this long, rambling narrative is Sir Francis Varney, a tall, gaunt figure with cadaverous features, who is made even more frightening to look at by his glassy eyes, taloned hands, and fang-like teeth. He is also incredibly strong, can move about rapidly, and is a master of disguise. Even on those occasions where he is seemingly killed, he is subsequently revived by the Moon’s rays, allowing him to resume his nefarious activities. Finally, after an interminable series of escapades, Varney becomes tired of his life of horror, and ends it all by throwing himself into the crater of Mount Vesuvius. Currently available in a number of paperback editions, in which the novel’s authorship is attributed to either James Malcolm Rymer or Thomas P. Prest, this crudely-written ‘penny dreadful’ is really only noteworthy for the influence it had on later writers, who reworked the variations on the vampire theme which it had introduced.

In comparison with the previous decade, the 1850s were lean years for vampire fiction. The only work of any significance was Charles Wilkins Webber’s Spiritual Vampirism (1853), which had the distinction of being the first novel to have psychic vampirism as its theme. The following decade was more fruitful, producing some notable short stories featuring female vampires. Of these, none are more highly regarded than Ivan Turgenev’s ‘Phantoms’ (1864), the hero of which is repeatedly visited at night by a phantasmal female figure, who he suspects is secretly sucking his blood. The first vampire story by an Australian author, ‘The White Maniac: A Doctor’s Tale’ (1867), by Mary Fortune, centres on events that take place inside a strange house where everything in it is coloured white. A doctor’s desire to solve the mystery leads to the shocking discovery that this has been done by the owner of the property to placate his ward, a beautiful young noblewoman, who suffers from a rare type of anthropophagy, making her prone to homicidal rages whenever she sees something coloured scarlet. One of the earliest appearances of the ‘vamp’ – the name usually given to a heartless, man-eating seductress – was in ‘A Vampire,’ an episode in G. J. Whyte-Melville’s Bones and I; or, The Skeleton at Home (1868). Calling herself Madame de St Croix, this insatiable sexual vampire has remained youthful and desirable over many years and has acquired a string of lovers, all of whom have died in mysterious circumstances. On more traditional lines is William Gilbert’s ‘The Last Lords of Gardonal’ (1867), in which a nobleman is attacked by his beautiful bride on their wedding night, unaware that she has been brought back to life by a wizard’s magical powers, and can only survive in her present state by sucking her husband’s blood.

Vampirism of a much more unusual kind occurs in Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Lost in a Pyramid; or, The Mummy’s Curse’ (1869). In this chilling tale an ancient curse is activated when a seed found in a mummy’s wrappings is planted, and the white flower it bears slowly absorbs the vitality of a young woman after she pins it to her dress. One of the least effective stories from the 1860s is ‘The Vampire; or, Pedro Pacheco and the Bruxa’ (1863), by William H. G. Kingston. Although the main narrative is preceded by a fascinating account of the activities of vicious Portuguese vampires called Bruxas, their non-appearance in the story itself is something of a letdown.

The only vampire-themed novels from the 1860s remembered today are Le Chevalier Ténèbre (1860) and La Vampire (1865), both of which were written by Paul Féval. In the earlier novel, two notorious male siblings, one a ghoul, the other a vampire, periodically emerge from their 400-year-old graves and go on the rampage. The later novel features the equally formidable Countess Addhema – a pale, fleshless old woman with a bald pate – who is temporarily transformed into a ravishing beauty every time she applies to her bare skull a living head of hair torn from one of her beautiful young female victims. Féval added to his tally of vampire novels in the following decade, penning La Ville Vampire in 1874. A parody of early nineteenth century Gothic novels, its unlikely heroine is the real-life author Ann Radcliffe, who mounts an expedition to find the legendary vampire-infested city of Selene, hoping to rescue a friend who has been taken there following her abduction by the evil vampire lord Otto Goetzi.

The first story to feature a lesbian vampire was Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘Carmilla’ (1871). In this frequently anthologised classic a young woman named Laura is visited nightly in her bedchamber by the new house guest, the alluring Carmilla, and is drawn into an increasingly intimate relationship with her. Thereafter, Laura’s health declines, raising fears that she is the victim of a vampire. It eventually transpires that Carmilla is the revenant of Countess Mircalla Karnstein, who has been dead for more than one hundred and fifty years.

In the 1880s – looked on today as the beginning of supernatural fiction’s golden era – there was a noticeable broadening of the vampire story’s scope. For example, bigotry, and the tragic circumstances that may arise from it, provides the basis for Eliza Lynn Linton’s ‘The Fate of Madame Cabanel’ (1880), in which a young Englishwoman living among superstitious French peasants is brutally murdered after being mistaken for a vampire. In contrast, Phil Robinson’s ‘The Man-Eating Tree’ (1881) is about an arboreal vampire poetically described as ‘a great limb with a thousand clammy hands.’ In another offbeat story, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs’ ‘Manor’ (1884), a drowned sailor’s corpse becomes reanimated and issues from its grave at night to suck the blood of a youth who had been in a homosexual relationship with the dead man. A unique story from 1886 which is still capable of sending shivers up and down readers’ spines is Guy de Maupassant’s ‘The Horla,’ the narrator of which fears he has become the plaything of an invisible vampire. Psychic vampirism is the theme of Frank R. Stockton’s ‘A Borrowed Month’ (1886), in which a young man suffering from a debilitating illness discovers that, by the force of his will, he can draw energy and vitality from his friends. Psychic vampirism of a more sinister kind is practised in Conan Doyle’s ‘John Barrington Cowles’ (1884); this time the perpetrator is a beautiful, sadistic woman who luxuriates in her ability to destroy her lovers.

Sabine Baring-Gould’s ‘Margery of Quether’ (1884) is, without doubt, one of the oddest vampire stories in English literature. Satirising the politics of its day – with many references to the controversial reforms to the land laws – it was popular for a while, but soon sank into a lengthy period of obscurity. However, since its inclusion in Vintage Vampire Stories (2011) this story’s cynical humour can now be savoured once again. A more conventional story, Aleksey K. Tolstoy’s ‘The Family of the Vourdalak,’ draws its inspiration from Serbian folklore. Originally written in 1839, but not published until 1884, it tells of a French diplomat’s frightening encounter with vampires, which happens when he stops for the night at a village, and discovers it is deserted apart from a single family, all of whom have been transformed into vampires after the head of the household was bitten by one.

Two other significant stories from the 1880s are ‘Ken’s Mystery’ (1883), by Julian Hawthorne, and ‘A Mystery of the Campagna’ (1887), by ‘Von Degen’ (pseudonym of Anne Crawford). In the former, the hero becomes romantically entangled with a legendary vampiress after travelling with her into the past through the agency of a magic ring; and, in the latter, a composer holidaying in Italy becomes the victim of a centuries-old vampiress whose sarcophagus is concealed in an underground burial chamber.

As might be expected from one of the most fertile periods in the history of supernatural fiction, the final decade of the nineteenth century yielded a rich harvest of vampire stories, several of which are among the finest ever written. Particularly outstanding is Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘The Parasite,’ which is a compelling tale about a psychic vampire. Originally published in Harper’s Weekly, 10 November–1 December 1894, it revolves around the machinations of a frail, middle-aged spinster who is able to control the thoughts and actions of other people by her amazing mental powers. In particular, she conceives a passion for a university professor, whom she hypnotises in an attempt to make him reciprocate her love, eventually resorting to vampiric possession when this ploy fails.

One of the few stories from the 1890s to feature a psychic vampire of the male gender is ‘Old Aeson’ (1890), by Arthur Quiller-Couch, which tells how a man who gives shelter in his home to a decrepit stranger soon lives to regret his charity when his guest usurps his position in the household by stealing his youth and most of his substance. Two other stories from the 1890s with psychic vampirism as their main motif are ‘A Modern Vampire’ (1894), by W. L. Alden, in which an author has his energy drained by a pretty young woman he has befriended; and ‘A Beautiful Vampire’ (1896), by Arabella Kenealy, whose central character, a menopausal woman, steals beauty and sexual energy from those around her in order to remain attractive to members of the opposite sex.

New medical procedures being introduced around this time may have inspired ‘Good Lady Ducayne’ (1896), by Mary E. Braddon. In this lacklustre yarn a latter-day Elizabeth Bathory has survived well beyond the normal lifespan by getting her private physician to inject her with blood he has drained from his employer’s young female companions, all of whom fade away and die. A far superior story by this author is ‘Herself’ (1894), which was included in Vintage Vampire Stories after years of undeserved neglect. Set in Italy, it chronicles the gradual decline in health of a bubbly young woman after she becomes morbidly enraptured by an antique mirror, which steals some of her vitality every time she gazes into its depths.

A female vampire of royal blood, who comes to life and sucks the blood of an Englishman after her ancient resting-place is disturbed, is featured in ‘The Tomb Among the Pines’ (1894), an uncredited story which was initially published in the British periodical Household Words. One of the most exotic vampiresses from the 1890s is the evil enchantress in ‘The Crimson Weaver’ (1895), by R. Murray Gilchrist. Incredibly old yet stunningly beautiful, she lures a knight into her magical domain and kills him horribly after enslaving him with a kiss. Similarly, in Arthur Quiller-Couch’s ‘The Legend of Sir Dinar’ (1891) an Arthurian knight seeking the Holy Grail is held in thrall by a beautiful vampiress who steals his youth. There can be no doubt, however, that the deadliest female vampire from this period is Annette, the central character in Dick Donovan’s 1899 story ‘The Woman with the “Oily Eyes”.’ An irredeemably evil monster in womanly form, she attracts upright men against their will and brings about their destruction, using her mesmeric eyes to subjugate them. Another story from 1899, Vincent O’Sullivan’s ‘Will,’ is notable for its effective use of the ‘biter bit’ scenario. Similar in style to Poe’s macabre tales, it tells how a man with an irrational hatred for his wife relentlessly draws out and absorbs her life force by gazing at her intently for hours on end, until eventually she dies. The tables are turned, however, when the dead woman constantly haunts her husband, sapping his will to live.

One of the most unconventional vampire stories from the late Victorian era is ‘A Kiss of Judas’ by ‘X. L.’ (pseudonym of Julian Osgood Field). First published in 1893, it is based on the curious legend of the Children of Judas, the substance of which is that the lineal descendants of the arch-traitor are prowling about the world intent on doing harm to anyone who offends them. Luring their victims into their clutches by any means necessary, they kill them with one bite or kiss, which is so deadly it drains the blood from their bodies, leaving a wound on the flesh like three X’s, signifying the thirty pieces of silver paid to Christ’s betrayer. Another offbeat story is Count Eric Stenbock’s ‘The True Story of a Vampire,’ which comes from his 1894 collection Studies of Death. Count Vardalek, whose activities this story chronicles, is a male version of Le Fanu’s Carmilla, but whereas she was homoerotically attracted to another woman, Vardalek has similar feelings about a young boy.

‘The Priest and His Cook’ and ‘The Story of Jella and the Macic’ are two folkloric tales that have recently been extracted from The Pobratim, an 1895 novel by Professor P. Jones. The former appeared for the first time in Vintage Vampire Stories, and the latter makes its debut in the present volume. Two better-known stories from the 1890s that have turned up in vampire anthologies on more than one occasion are ‘Let Loose’ (1890), by Mary Cholmondeley, and ‘The Death of Halpin Frayser’ (1891), by Ambrose Bierce. Both are difficult to classify, but a case for including them in the vampire canon can be made if one views them as stories about the dead returning to wreak vengeance on the living, using methods akin to vampirism. There are, however, no such doubts about the eligibility of H. B. Marriott Watson’s ‘The Stone Chamber’ (1898) to be categorised as a vampire story. Set in rural England, it tells how guests staying at Marvyn Abbey awake in the morning feeling exhausted and have red marks on their necks, a tell-tale sign that they have been preyed upon by a vampire.

Stories about vampires of the non-human kind were also popular during the final decade of the nineteenth century. For instance, in H. G. Wells’ ‘The Flowering of the Strange Orchid’ (1894), a collector of exotic plants is attacked by a bloodsucking orchid growing in his hothouse; while in Fred M. White’s ‘The Purple Terror’ (1899) a group of explorers are menaced by vampire-vines in the Cuban jungle. Even more loathsome is the vampire-like monstrosity in Erckmann-Chatrian’s ‘The Crab Spider’ (1893), in which animals and people who enter a cave at a German health resort are attacked and have their bodies drained of blood by a giant arachnid. In another fascinating story, Sidney Bertram’s ‘With the Vampires’ (1899), explorers journeying up the Amazon encounter cave-dwelling vampire bats. The same geographical location is also the setting for Phil Robinson’s ‘The Last of the Vampires’ (1893), in which a German trader comes across a huge vampire-pterodactyl, to which human sacrifices are made.

A psychic detective whose cases sometimes involved vampire-like phenomena is Flaxman Low, who appeared in a series of allegedly real ghost stories in Pearson’s Magazine between 1898 and 1899 under the byline of E. & H. Heron, a pseudonym used by the mother-and-son writing team Kate and Hesketh Prichard. In ‘The Story of Baelbrow,’ for instance, Low investigates mysterious deaths at a reputedly haunted house, and discovers that a previously ineffectual spirit-vampire has become a deadly killer by activating an Egyptian mummy in his client’s private museum. In another exploit, ‘The Story of the Moor Road,’ a malevolent elemental becomes palpable after absorbing an invalid’s vitality; and, in ‘The Story of the Grey House,’ guests staying at a secluded country house are strangled and drained of blood by a demoniacal creeper growing in the shrubbery.

The 1890s was also a productive decade for vampire novels, but apart from a select few most are forgotten today. Towering above them all is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which, since its launch in 1897, has gone on to sell millions of copies around the world and is undoubtedly the most influential vampire novel ever written. Surviving changes in fashion and numerous indignities at the hands of clumsy editors, it has, over time, earned itself a unique place in the vampire canon, and has deservedly achieved the status of a classic of English literature. The enduring appeal of this novel is primarily due to its sensational plot and Stoker’s spellbinding narrative power, but it is also noteworthy for two other reasons. Firstly, it has systemised the rules of literary and cinematic vampirology for all time, and secondly we have in Count Dracula the definitive incarnation of the human bloodsucker.

The only novel from the 1890s to rival Stoker’s magnum opus in popularity is H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), which was the first novel to feature alien vampires. For the benefit of those who haven’t read Wells’ classic, or are only familiar with the plot through watching adulterated film versions, the vampires are the invading Martians, who, we learn, turned to vampirism after their digestive tracts atrophied almost completely, making them solely reliant on blood for sustenance. Initially they preyed on their fellow Martians, but when supplies of the life-giving fluid became exhausted they were forced to look beyond their own planet for survival, and found just what they needed on neighbouring Earth.

J. Maclaren Cobban’s Master of His Fate (1890), which was strongly influenced by Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, concerns the tragic fate of a scientist who has discovered a formula that enables him to renew his youth by absorbing energy from other people merely by touching them. However, as the necessity to absorb larger amounts of energy arises, he is forced to commit suicide to prevent the deaths of his ‘donors,’ who include the woman he loves. Another novel probably inspired by Stevenson’s split-personality classic is Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). While not usually thought of as a vampire, Gray can quite legitimately be likened to one in view of his destructive, self-indulgent lifestyle, an essential part of which is the consumption of other people’s life-energy in order to gain eternal youth. Vampirism of a similar nature is practised in H. J. Chaytor’s The Light of the Eye (1897) and L. T. Meade’s The Desire of Men: An Impossibility (1899). In the former, a man’s eyes have the power to suck out people’s vitality, while Meade’s thriller revolves around weird experiments in a strange house, where the aged regain their lost youth at the expense of the young. Other novels from the 1890s with vampirism as the main or subsidiary theme are: The Soul of Countess Adrian (1891), by Mrs Campbell Praed; The Strange Story of Dr Senex (1891), by E. E. Baldwin; Sardia: A Story of Love (1891), by Cora Linn Daniels; The Fair Abigail (1894), by Paul Heyse; The Lost Stradivarius (1895), by J. Meade Falkner; Lilith (1895), by George MacDonald; The Blood of the Vampire (1897), by Florence Marryat; In Quest of Life (1898), by Thaddeus W. Williams; and The Enchanter (1899), by U. L. Silberrad.

The only vampire novels from the first decade of the twentieth century of any significance are In the Dwellings of the Wilderness (1904), by C. Bryson Taylor; The Woman in Black (1906), by M. Y. Halidom; and The House of the Vampire (1907), by George Sylvester Viereck. In the first of these, a party of American archaeologists is attacked vampirically by the revivified mummy of an Egyptian princess; while the novel by the pseudonymous M. Y. Halidom features a glamorous seductress who has retained her beauty and youthful appearance for centuries by sucking the blood of her lovers. In contrast, the vampire in Viereck’s novel – an arrogant, self-centred writer – acts like a psychic sponge, stealing the most creative thoughts of his protégés and passing them off as his own.

A short story from the turn of the century which has remained popular over the years is F. G. Loring’s ‘The Tomb of Sarah.’ First published in the December 1900 issue of Pall Mall Magazine, it centres on the nocturnal activities of an undead witch who has been accidentally released from the confinement of her tomb during renovations to a church. For a while her nightly forays in search of blood cause great concern among the local community, but she is eventually caught and permanently laid to rest by the time-honoured ritual of driving a stake through her heart. A much more sensational story from this period, Richard Marsh’s ‘The Mask’ (Marvels and Mysteries, 1900), is about a homicidal madwoman adept in the art of mask-making who transforms herself into a raving beauty and tries to suck the blood of the story’s hero. Female vampires are also featured in two stories in Hume Nisbet’s collection Stories Weird and Wonderful (1900). In ‘The Vampire Maid’ a weary traveller finds lodgings at an isolated cottage on the Westmorland moors, only to be preyed on during the night by the landlady’s vampire daughter; and in ‘The Old Portrait’ a woman depicted in a painting comes to life and tries to suck out the vitality of the picture’s owner with a long, lingering kiss. Offering more substantial fare, Phil Robinson’s ‘Medusa,’ a well-crafted story from Tales by Three Brothers (1902), is about a seductive femme fatale who feeds on the life force of her male admirers. A more subtle threat is posed in Mary E. Wilkins Freeman’s ‘Luella Miller’ (1902), the title character of which unconsciously absorbs the vitality of her nearest and dearest, causing them to languish while she blooms. On more traditional lines is F. Marion Crawford’s vampire classic ‘For the Blood is the Life’ (1905), in which a gypsy girl returns from the dead to vampirize the man who had spurned her love. In another first-rate story, R. Murray Gilchrist’s ‘The Lover’s Ordeal’ (1905), a young woman challenges her fiancé to pass through an ordeal before she will consent to marry him. This involves spending the night at a haunted house; but, unbeknown to the couple, a beautiful vampiress is lurking in one of the rooms, waiting patiently for her next victim to come along. An inconsequential piece, by comparison, is ‘The Vampire,’ by Hugh McCrae, which was originally published under the pseudonym ‘W. W. Lamble’ when it appeared in the November 1901 edition of The Bulletin.

One of the Edwardian era’s finest vampire stories is ‘Count Magnus,’ by M. R. James, which has been anthologised many times since its debut in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904). Among this author’s spookiest tales, it chronicles the events leading up to the gruesome death of an English scholar, who becomes a doomed man after delving too deeply into suppressed legends about a notorious seventeenth-century Swedish nobleman. A minor story, ‘The Vampire’ (1902), by Basil Tozer, has seemingly sunk into oblivion, a fate that may well have befallen Frank Norris’s ‘Grettir at Thorhall-stead’ (1903) had it not been rescued from obscurity by fantasy historian Sam Moskowitz, who reprinted it in his 1971 anthology Horrors Unknown. Not entirely original, Norris’s story is a retelling of an episode in Grettir’s Saga, in which the legendary Icelandic hero has a fateful encounter with a vampire. Coincidentally, the same episode also provided the inspiration for Sabine Baring-Gould’s ‘Glámr,’ which was included in his A Book of Ghosts (1904). Another vampire story from this collection is ‘A Dead Finger,’ in which the hapless protagonist is preyed on by the disembodied spirit of a dead man, which is gradually stealing his vitality in an attempt to create a new body for itself. On similar lines to this story are Luigi Capuana’s ‘A Vampire’ (1907), which describes how the disembodied spirit of a woman’s deceased husband attempts to suck the blood of her infant child; and Lionel Sparrow’s ‘The Vengeance of the Dead’ (1910), in which a thoroughly evil man has, since his demise, existed in a state of life-in-death by stealing vitality from the living and transferring it to his corpse. More ambitiously, the unscrupulous scientist in C. Langton Clarke’s ‘The Elixir of Life’ (1903) has isolated the vitic force and found a way to transfer it from others to himself, thereby attaining a kind of immortality. More conventional in their treatment of the vampire theme are ‘The Vampire Nemesis’ (1905), by ‘Dolly,’ and ‘The Singular Death of Morton’ (1910), by Algernon Blackwood. In the former story a suicide is reincarnated as a giant vampire bat; and, in the latter, two men holidaying in France encounter a sinister woman, who lures one of them to a cemetery and sucks all the blood from his body.

Some of the best stories from the Edwardian era feature vampires in unusual guises. In Morley Roberts’ ‘The Blood Fetish’ (1909), for example, a severed hand lives on as an independent entity by absorbing the blood of both animal and human victims. In another morbid tale, Horacio Quiroga’s ‘The Feather Pillow’ (1907), a young woman has all the blood gradually sucked out of her by a monstrous insect secreted inside the pillow on her bed; and in F. H. Power’s ‘The Electric Vampire’ (1910) a mad scientist creates a giant, electrically-charged insect which feeds on blood. Even more bizarre is Louise J. Strong’s ‘An Unscientific Story’ (1903), in which a professor who has succeeded in breeding the ‘life-germ’ in his laboratory soon realises the folly of his experiments when his creation grows at a fantastic rate and within a short time forms itself into a humanoid creature which exhibits a craving for blood.

The first anthology to gather together a sizeable number of stories from this golden age of vampire fiction was Richard Dalby’s Dracula’s Brood (1987), which contained twenty-three rare stories written by friends and contemporaries of Bram Stoker. Then, after years of searching through dusty old books and defunct magazines, Richard and fellow vampire enthusiast Robert Eighteen-Bisang compiled an even rarer collection of stories for their 2011 anthology Vintage Vampire Stories. Now, after more diligent searching, Richard and I have put together this stunning new collection of stories, nearly all of which have been unavailable for many years, and include several forgotten gems whose resurrection from an undeserved obscurity should finally bring them the recognition they deserve.

BRIAN J. FROST

THE BRIDE OF THE ISLES (#ulink_42704a7c-fedd-5fae-8534-ca853e52b260)

A Tale Founded on the Popular Legend of the Vampire

Anonymous

When this story, which is based on James Robinson Planché’s play The Vampire; or, The Bride of the Isles, received its first publication in 1820, the publisher, J. Charles of Dublin, took the liberty of falsely attributing it to Lord Byron, and the real author is unknown. Nevertheless, it is an excellent example of the bluebook or ‘Shilling Shocker,’ which were the terms usually used to describe short Gothic tales published in booklet form during the early 19th century. Retailing between sixpence and a shilling, they were about four by seven inches in size, and their closely printed pages were stitched into a cover made of flimsy blue paper. These luridly illustrated publications were especially popular with members of the lower classes, many of whom craved the thrill of reading stories revolving around shocking, mysterious and horrid incidents, but couldn’t afford to buy expensive Gothic novels, which were often published in three volumes. A copy of the rare 1820 first edition, complete with its coloured frontispiece, fetched £2000 at auction three years ago.

‘THOUGH the cheek be pale, and glared the eye, such is the wondrous art the hapless victim blind adores, and drops into their grasp like birds when gazed on by a basilisk.’

THERE IS A popular superstition still extant in the southern isles of Scotland, but not with the force as it was a century since, that the souls of persons, whose actions in the mortal state were so wickedly atrocious as to deny all possibility of happiness in that of the next; were doomed to everlasting perdition, but had the power given them by infernal spirits to be for a while the scourge of the living.

This was done by allowing the wicked spirit to enter the body of another person at the moment their own soul had winged its flight from earth; the corpse was thus reanimated – the same look, the same voice, the same expression of countenance, with physical powers to eat and drink, and partake of human enjoyments, but with the most wicked propensities, and in this state they were called vampires. This second existence as it may not improperly be termed, is held on a tenure of the most horrid and diabolical nature. Every All-Hallow E’en, he must wed a lovely virgin, and slay her, which done, he is to catch her warm blood and drink it, and from this draught he is renovated for another year, and free to take another shape, and pursue his Satanic course; but if he failed in procuring a wife at the appointed time, or had not opportunity to make the sacrifice before the moon set, the vampire was no more – he did not turn into a skeleton, but literally vanished into air and nothingness.

One of these demoniac sprites, Oscar Montcalm, of infamous notoriety in the Scotch annals of crime and murder (who was decapitated by the hands of the common executioner), was a most successful vampire, and many were the poor unfortunate maidens who had been sacrificed to support his supernatural career, roving from place to place, and every year changing his shape as opportunity presented itself, but always chosing to enter the corpse of some man of rank and power, as by that means his voracious appetite for luxury was gratified.

Oscar Montcalm had seen, and distantly adored in his mortal state, the superior beauty of the Lady Margaret, daughter of the Baron of the Isles, the good Lord Ronald; but, such was his situation, he had not dared to address her; however, he did not forget her in his vampire state, but marked her out for one of his victims, in revenge for the scorn with which he had been treated by her father.

Lady Margaret, though lovely and well proportioned, entered her twentieth year unmarried, nor had she ever been addressed by a suitor whom she could regard with the least partiality, and with much anxiety she sought to know whether she should ever enter into wedlock, and what sort of person her future lord would be. With credulity pardonable to the times in which she lived, and the narrow education then given to females, even of rank, she consulted Sage, Seer and Witch, as to this important event; but it is not to be wondered at that she met with many contradictions, everyone telling a different tale. At length urged on by the irresistible desire to pry into futurity, she repaired with her two maidens, Effie and Constance, to the Cave of Fingal, where, cutting off a lock of her hair, and joining it to a ring from her finger, she cast it into the well, according to the directions she had received from Merna, the Hag of the mountains, who had instructed the fair one as to this expedition.

No sooner was the ring flung into the well than a dreadful storm arose; the torches, which the attendant maidens had borne, were extinguished, and the immense cave was in utter darkness: loud and dreadful was the thunder, accompanied by a horrid confusion of sounds, which beggars description.

Margaret and her companions sunk on their knees; but they were too stupefied with horror to pray, or to endeavour to retrace their way out of this den of horrors. Of a sudden, the cave was brilliantly illuminated, but with no visible means of light, for there were neither torch, lamp, or candle. Solemn music was heard, slow and awfully grand, and in a few minutes two figures appeared, one heavy, morose in countenance, and clad in dark robes, who announced herself as Una, the spirit of the storm, and touching a sable curtain, discovered to the view of Margaret the figure of a noble young warrior, Ruthven, Earl of Marsden, who had accompanied her father to the wars. Again the storm resounded, the curtain closed, and the cave resumed its darkness; but this was only transient – the brilliant light returned – Una was gone, and the light figure, dressed in transparent robes, sprinkled over with spangles remained. With her wand she pulled aside the curtain, and a young man of interesting appearance was visible, but his person was a stranger to the fair one. Ariel, the spirit of the Air, then waved her hand to the entrance of the cave, as a signal for them to depart, and bowing low, they withdrew, amid strains of heart-thrilling harmony, rejoiced to find themselves once more in an open space, and they happily returned in safety to the baron’s castle. The Lady Margaret was well pleased with what she had seen, as promising her two husbands, though she was somewhat puzzled by calling to mind a couplet that Ariel had repeated three or four times, while the curtain remained undrawn.

‘But once fair maid, will you be wed,

You’ll know no second bridal bed.’

What could this mean? Surely she would never stoop to illicit desires or intrigue? She thought she knew her own heart too well.

The vampire had seen into the designs of Margaret to visit the Cave of Fingal, and he sought out Ariel and Una, to whom, by virtue of his supernatural rights, he had easy access. The spirit of the air would not befriend him, but the spirit of the storm assisted him to pry into futurity; and to suit his views, she presented the figure of Ruthven, Earl of Marsden. In the meantime, Marsden had the good fortune to save Lord Ronald’s life in the battle, and the wars being ended, or at least suspended for a time, he invited the gallant youth home with him to his castle, to pass a few months amid the social rites of hospitality and the pleasure of the chase.

The Lady Margaret received her father with dutiful affection, and gratitude to providence for his safe return, and she beheld young Marsden with secret delight; but when informed that he had preserved the baron from overpowering enemies, her gratitude knew no bounds, and she looked so beautiful and engaging, while returning her thankful effusions for the service he had rendered her father, that the earl could not resist the impulse, and from that hour became deeply enamoured of the lovely fair one.

Marsden’s rank and birth were unexceptionable but his fortune was very inadequate to support a title, which made him (added to the love of military glory) enter into the profession of arms, of which he was an ornament.

Margaret was the only child, and her father abounding in wealth and honours; it might therefore be presumed that an ambition might lead him to form very exalted views for the aggrandisement of his heiress; and so he had, but perceiving how high his preserver stood in the good graces of his darling child, and that the passion was becoming mutual, he resolved not to give any interruption to their happiness, but if Marsden could win Margaret to let him have her, as a rich reward for the service he had performed amid the clang of arms.

Parties were daily formed by the baron for the chase, hawking, or fishing, while the evening was given to the festive dance, or the minstrels tuned their harps in the great hall, and sang the deeds of Scottish chiefs, long since departed, amongst whom the heroic Wallace was not forgot.