Полная версия:

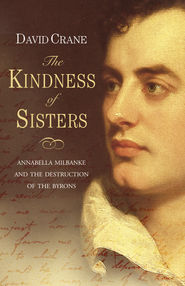

The Kindness of Sisters: Annabella Milbanke and the Destruction of the Byrons

‘You ask “if I am sure of myself”’ he had already written to Lady Melbourne ten days earlier, after first hesitantly broaching the idea of Annabella to her in a letter from Cheltenham on the 13th,

I answer – no – but you are, which I take to be a much better thing. Miss M. I admire because she is a clever woman, an amiable woman & of high blood, for I still have a few Norman & Scotch inherited prejudices on the last score, were I to marry. As to Love, that is done in a week (provided the Lady has a reasonable share) besides marriage goes on better with esteem & confidence than romance, & she is quite pretty enough to be loved by her husband, without being so glaringly beautiful as to attract too many rivals.39

At the beginning of October Lady Melbourne approached her niece on his behalf, and on the 12th received Annabella’s refusal from Richmond, complete with a ‘Character’ of Byron explaining her decision. ‘The passions have been his guide from childhood,’ she wrote, up on her ‘high stilts’ as her aunt described her,

and have exercised a tyrannical power over his very superior intellect. Yet among his dispositions are many which deserve to be associated with Christian principles – his love of goodness in its chastest form, and his abhorrence of all that degrades human nature, prove the uncorrupted purity of his moral sense.

There is a chivalrous generosity in his ideas of love and friendship, and selfishness is totally absent from his character. In secret he is the zealous friend of all human feelings; but from the strangest perversion that pride ever created, he endeavours to disguise the best points of his character. When indignation takes possession of his mind – and it is easily excited – his disposition becomes malevolent. He hates with the bitterest contempt; but as soon as he has indulged those feelings, he regains the humanity which he had lost – from the immediate impulse of provocation – and repents deeply.40

It is difficult to be sure of Byron’s real feelings at this rejection, or even whether he knew himself, but whatever they were he would never have dropped the tone of cool worldliness with Lady Melbourne that had become their common language. ‘Cut her! My dear Ly. M. marry – Mahomet forbid!’ – he wrote to her on receiving the news, anxious to allay any suspicion of resentment,

I am sure we will be better friends than before & if I am not embarrassed by all this I cannot see for the soul of me why she should – assure her con tutto rispetto that The subject shall never be renewed in any shape whatever, & assure yourself my carissima (not Zia what then shall it be? Chuse your own name) that were it not for this embarras with C I would much rather remain as I am. – I have had so very little intercourse with the fair Philosopher that if when we meet I should endeavour to improve our acquaintance she must not mistake me, & assure her I never shall mistake her … She is perfectly right in every point of view, & during the slight suspense I felt something very like remorse for sundry reasons not at all connected with C nor with any occurrence since I knew you or her or hers; finding I must marry however on that score, I should have preferred a woman of birth & talents, but such a woman was not at all to blame for not preferring me; my heart never had an opportunity of being much interested in the business, further than that I should have very much liked to be your relation. – And now to conclude like Ld. Foppington, “I have lost a thousand women in my time but never had the ill manners to quarrel with them for such a trifle.”41

The address on this letter – Cheltenham again – suggests, though, that Byron’s good humour was not simply feigned for Lady Melbourne’s benefit. He had gone to the fashionable spa town for the waters earlier in the summer, but long after it had been abandoned by most of London society he was still there, held by a growing fascination with that other ‘Aspasia’ of Regency England that he would have been reluctant to admit to Lady Melbourne, the beautiful, serially faithless forty-year-old Countess of Oxford, Jane Harley.

There is as much pseudo-psychological nonsense talked of Byron’s predilection for older women – as if everyone over the age of thirty were somehow identical – as there is over his fastidious distaste at the sight of a woman eating.* In the wake of Childe Harold it was inevitable that he should gravitate towards the great hostesses who dominated Whig society, but among even that disparate group it would be hard to imagine two women with less in common than Lady Melbourne and Lady Oxford, the one all caution, cynicism, and dynastic ambition, the other generous, impulsive, radical and careless of the proprieties she had so successfully defied from the first loveless years of marriage.

The daughter of a clergyman, Jane Scott had been born in Inchin, and at the age of twenty-two ‘sacrificed’, as Byron later told Medwin, ‘to one whose mind and body were equally contemptible in the scale of creation’43. If Lord Oxford had never been much of a match for his dazzling and ambitious wife, however, he was no gaoler either, and by the time that she began her affair with Byron the ‘grande horizontale’ of Whig political radicalism was already the mother of five children by as many fathers, ‘a tarnished siren of uncertain age’, as Lord David Cecil described her with patrician distaste,

who pursued a life of promiscuous amours on the fringe of society, in an atmosphere of tawdry eroticism and tawdrier culture. Reclining on a sofa, with ringlets disposed about her neck in seductive disarray, she would rhapsodise to her lovers on the beauties of Pindar and the hypocrisy of the world.44

Byron had first met her during the London season, but it was at Cheltenham and then at Eywood, the Oxfords’ country house in Herefordshire, that their friendship developed into the infatuation that absorbed him for the next six months. ‘She resembled a landscape by Claude Lorraine’, Lady Blessington – no ingenue herself – recalled him saying,

‘with a setting sun, her beauties enhanced by the knowledge that they were shedding their last dying beams, which threw a radiance around. A woman (continued Byron) is only grateful for her first and last conquest. The first of poor dear Lady [Oxford’s] was achieved before I entered on this world of care, but the last I do flatter myself was reserved for me, and a bonne bouche it was.’45

It is impossible to imagine Byron speaking of Lady Melbourne in this tone, but if Lady Oxford never exerted the same dominance over him as the ‘spider’ had done, in the sensual and intellectual licence of the ‘bowers of Armida’46, as he labelled Eywood, he found a retreat from any fleeting disappointment at Annabella’s rejection and the continuing assaults of Caroline Lamb. ‘I mean (entre nous my dear Machiavel)’, he had written to Lady Melbourne,

to play off Ly. O against her, who would have no objection perchance but she dreads her scenes and has asked me not to mention that we have met to C or that I am going to E.47

‘I am no longer your lover’, he wrote to Caroline herself, as good as his word, if the letter she reproduced in Glenarvon is the faithful copy of Byron’s that she claimed it to be,

and since you oblige me to confess it, by this truly unfeminine persecution, – learn, that I am attached to another; whose name it would of course be dishonorable to mention. I shall ever remember with gratitude the predilection you have shewn in my favor. I shall ever continue as your friend, if your ladyship will permit me so to style myself; and as a first proof of my regard, I offer you this advice, correct your vanity, which is ridiculous; exert your absurd caprices upon others; and leave me in peace.48

In spite of the callousness of this letter – a cruelty that forms the counterpart to Byron’s generosity – his relationship with Caroline had stirred him in ways that Lady Oxford never did. There is no disguising the sense of almost bloated content that runs through many of Byron’s letters from Eywood, and yet at some level both he and Lady Oxford knew that the demons that drove him were not ones that could be contained within Armida’s bowers or the boundaries of Whig politics she had marked out for him.

For all the sexual and intellectual freedom Byron enjoyed at Eywood, the affair with Lady Oxford was too tame ever fully to satisfy him. In all his most important relationships there had been an element of risk and social danger, but there was something almost institutional in the sexual abandon of Lady Oxford, a kind of licensed immorality that paradoxically took Byron closer to one branch of the Whig political establishment than he had ever been before.

And there was never a time, either, when Byron was more dangerous than when made aware of how little he wanted what English society had to offer him. ‘I am going abroad again’, he announced in March 1813, in the middle of his affair with Lady Oxford,

… my parliamentary schemes are not much to my taste – I spoke twice last Session – & was told it was well enough – but I hate the thing altogether – & have no intention to ‘strut another hour’ on that stage.49

Byron was being partly disingenuous – for all the kind words that greeted his debut speech it had only had a limited impact – but his suppressed unease of this period was more than a defensive reflex to disappointment. It is clear from his own comments that he knew that he would never make a parliamentary orator, and yet it is hard to believe that success could any more have reconciled the creator of Childe Harold – still less the ‘Titan battling with religion and virtue’50 that Nietzsche admired in Byron – to the limitations of English public life and a career in politics.

If it seems inevitable that the young Nietzsche should be drawn to Byron – and in particular to the creator of the defiant Manfred – the quality that he most admired in him was the courage to follow his instincts that Lawrence also saw as the defining characteristic of the ‘aristocrat’. In his Hardy essay Lawrence wrote that ‘the final aim of every living thing … is the full achievement of itself’51, but as Byron’s affair with Lady Oxford guttered towards its untidy end, it was precisely that goal of self-realisation – the supreme ambition of the Romantic imagination – that he recognised with an ever increasing clarity he could never achieve in England.

In an age that is as ready to recognise the tyranny of sex as ours is, it is possibly enough to point out that for a man of Byron’s sexual ambivalence a country that still sent homosexuals to the gallows was no place to be. From the publication of the spurious ‘Don Leon’ poems in the mid-nineteenth century, Byron has always been an icon and spokesman for homosexual freedom, and yet the vital thing in this context is not so much the question of his sexual identity per se – who now cares? – but the wider issues of creative fulfilment or frustration with which it was inevitably and intimately bound.

For Byron, as for Lawrence, the test of ‘being’ was ‘doing’, and as the year dragged on he was conscious of how little he had achieved as a poet. For all his aristocratic disdain for the business of versifying he was keenly aware that he had ‘something within that “passeth show”’52, and yet for a man whose lameness, childhood and sexual ambiguities all supremely equipped him to challenge political, moral, or physical injustice in every form he found it, he had precious little to show. The adolescent anger of English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, which he had long since repudiated? The stagey and harmless posturing of Childe Harold? A clutch of cautiously disguised tributes to the dead Cambridge chorister, Edleston? ‘At five-and-twenty, when the better part of life is over’, he wrote in his journal,

one should be something; – and what am I? nothing but five-and-twenty – and the odd months.53

But if, in these early months of 1813, Byron still lacked what Lawrence called the ‘courage to let go the security, and to be54’, this sense of self-dissatisfaction and estrangement was gradually pushing him towards a crisis. As early as May he was writing to Lady Melbourne of the need to escape a world that was stifling him, and at the end of June he returned with increased irritation to the same theme. ‘I am doing all I can to be ready to go with your Russian’ [Prince Koslovsky, a visiting Russian diplomat], he told her,

depend upon it I shall be either out of the country or nothing – very soon – all I like is now gone – & all I abhor (with some few exceptions ) remains – viz – the R[egent] – his government – & most of his subjects – what a fool I was to come back – I shall be wiser next time.55

It is a curious, if somehow irrelevant, thought that Byron might have gone abroad in the summer of 1813, either with the Oxfords to Sicily as was planned at one time, or farther east to the Levant. Byron himself had such a strong sense of his own destiny that even with the benefit of hindsight it is hard to see his life in any other shape than that which it finally took, and if this ignores those elements of chance and sloth that right up to his death might have disposed of him in a dozen different ways, one only has to picture him for a moment harmlessly cruising the Mediterranean to recognise the inherent implausibility of the vision.

Because if Byron was to grow as a man or a poet, he did not need simply to escape England, but to smash with a complete and final violence everything that held him to it. In his relationship with Caroline Lamb during the previous year he had come dangerously close to doing this, and while he had pulled back from the edge then it was only a matter of time before he recognised that the conformist elements in his nature could never be squared with the vocation for opposition he claimed as the Byron birthright.

‘I have no choice’ – Byron put the words in Manfred’s mouth – and it is this sense of necessity that attracted both Lawrence and Nietzsche to the dramatic parabola of Byron’s life and career. There is of course a world of difference between the Lawrentian ‘aristocrat’ and the iibermensch that Nietzsche hailed in the figure of Manfred. Yet if Lawrence’s ultimate concern was with fulfilment in the deepest and most human sense of the word, he never shirked the fact that for an outsider of Byron’s stamp that inevitably meant war. ‘This is the tragedy’, Lawrence wrote,

… that the convention of the community is a prison to his natural, individual desire, a desire that compels him, whether he feels justified or not, to break the bounds of the community, lands him outside the pale, there to stand alone, and say: ‘I was right, my desire was real and inevitable; if I was to be myself I must fulfil it, convention or no convention …’56

It is this sense of inevitability that gives the air of a ‘phoney war’ to the period of Byron’s affair with Lady Oxford. When at the end of June she left England with her husband he confessed that he felt more ‘Carolinish’57 about it than he had expected, despite the fact that for all her attractions she could no more satisfy him than Caroline Lamb herself had done before her.

Still less could one of the great regnantes of Whig society answer his need for a rupture with everything that held him to England. It did not, though, matter. By the time that Lady Oxford finally sailed, on 28 June, the one woman had re-appeared in his life who could fill both roles: a woman who by her birth and temperament was not only uniquely placed to define the full nature of Byronic rebellion but also to meet with a peculiar psychological and emotional fitness what Lawrence called ‘the deepest desire’ of life,

a desire for consummation … a desire for completeness, that completeness of being which will give completeness of satisfaction and completeness of utterance.58

The woman in question was the Hon. Mrs Augusta Leigh, the twenty-nine-year-old daughter of Byron’s father by his first, scandalous, marriage to Amelia Darcy, Baroness Conyers in her own right and the wife of the heir to the Duke of Leeds, the Marquess of Carmarthen.

The son of that famous sailor and womaniser, ‘Foulweather Jack’, ‘Mad Jack’ Byron seemed ‘born for his own ruin, and that of the other sex.’59 Six years before Augusta’s birth, the dazzling and wealthy Marchioness had met and fallen for him, picnicked with him one day and abandoned her husband for him the next, living defiantly with him in a ‘vortex of dissipation’60 until a well-publicised divorce left her free to marry him and move to France.

Whatever fondness his son might retain for his memory, ‘Mad Jack’ was as callous a rake as eighteenth-century gossip portrayed him, with all the Byron charm and none of its generosity. For five years he lived off his wife’s fortune in either Chantilly or Paris, but when shortly after Augusta’s birth he lost wife and income together, Jack Byron abandoned the child to the first in a long succession of guardians and relatives, and set off on the predatory hunt for another heiress that finally led to Bath and Catherine Gordon.

For a few months, as a four-year-old, Augusta lived with her father and his pregnant new wife at Chantilly, but from the moment she was handed over to her grandmother, Lady Holderness, she left behind the depravation and uncertainty that was Jack Byron’s only obvious legacy to his children. During the crucial years when Catherine Gordon and her son were struggling under the indignities of poverty and isolation, the orphaned Augusta was growing up among a clutch of aristocratic relations into a tall and graceful girl, ‘light as a feather’, with a long, slender neck and heavy mass of light brown hair, a fine complexion, large mouth, retroussé nose, beautiful eyes, gentle manner, and a pathological shyness that eclipsed even that of her unknown Byron half-brother.61

If these formative years among her Howard cousins and the half-brothers and sisters of her mother’s first marriage gave Augusta an uncritical, aristocratic ease that Byron never matched, as a grounding in emotional subservience they had more corrosive consequences. There was a fundamental docility to her character that probably ran deeper than any social conditioning, but for a girl of such natural reticence and limited prospects, a childhood of gilded dependence in the great houses of her relations can only have compounded the instinct for self-surrender that was to mark her adult life.

It was an instinct confirmed, too, when after a six-year courtship she finally married her feckless cousin, George Leigh, and sank into a life of straitened domesticity from which she never escaped. Colonel George Leigh has always had one of those roles in the Byron story that never quite swells even to a walk-on part, but for his wife at least he was real enough, an irascible and incapable husband and father in equal measure, a cavalry officer whose career ended in financial scandal and a gambler whose sharpness, even in the world of Newmarket and the circles of the Prince of Wales, placed him on the wrong side of social acceptability.

It can seem at times as though Augusta only existed in and through other people, so it is little wonder that a woman with such a genius for self-effacement has always proved hard to pin down. From the first day that her character was dragged into the public domain it has been open season on her, but after a hundred and fifty years of legal and biographical prodding she remains as elusive and unknowable as ever, leaving behind only a kind of erotic charge that is as close as we can get to her, an impression of femininity so endlessly and placidly accommodating as to obliterate all individuality.

A ‘fieldsman’, Thomas Hardy wrote in Tess, is never anything more than a man in a field but a woman is continuous with the natural world, and something of that universality clings to the finest surviving image we have of Augusta Leigh. There is little contemporary evidence to suggest she ever looked like Hayter’s lovely drawing of her, but in the languor and passivity of that face, the tilt of the head and the long curve of the neck, he has surely left us the essential Augusta – the ‘sleepy Venus’ of Byron’s Don Juan, the Zuleika of The Bride of Abydos, the mother of seven children by a husband she hardly ever saw – the woman whose idle and easy sexuality could disturb and attract both men and women every bit as much as her half-brother’s flagrant aggression.

Augusta had first met Byron when she was a girl of seventeen and he an awkward and overweight schoolboy of thirteen. From their first exchanges of letters the two were natural allies in his endless battles with his mother, but in spite of a protective – and on his side almost seigneurial – affection they saw very little of each other as children. At the age of seventeen Augusta was already infatuated with her Leigh cousin, and as Byron himself moved from Harrow to Cambridge and then on to his travels in the east she inevitably became more of an idea than a reality to him.

In the long run there could have been nothing more dangerous than this legacy of intimacy and distance, and no more vulnerable time for Augusta to re-enter his life than the summer of 1813, when his affair with Lady Oxford was petering out and Caroline Lamb was taking her last melodramatic revenge. The correspondence between Byron and Augusta for the preceding months is missing, but it seems almost certainly his idea that she should come up to London. She had written to him the previous January in need of money to meet her husband’s gambling debts, and although financial troubles over Newstead left Byron in no position to help, his answer emphasises the sad hollowness she alone would fill. The ‘estate is still on my hands’, he began a long list of complaints, ‘& your brother not less embarrassed …

I have but one relative & her I never see – I have no connections to domesticate with & for marriage I have neither the talent nor the inclination – I cannot fortune-hunt nor afford to marry without a fortune … I am thus wasting the best part of my life daily repenting and never amending … I am very well in health – but not happy nor even comfortable – but I will not bore you with complaints – I am a fool & deserve all the ills I have met or may meet with.62

There was something prophetic in that last line, because almost from the moment she arrived in London, Byron seems to have been bent on disaster. If ‘form’ is anything to go by, he would inevitably have turned to someone on the rebound from Caroline and Lady Oxford, but if anyone might have done, Augusta seemed to offer everything, the excitement of novelty and the comfort of familiarity, the danger of the forbidden with the guarantee of safety implicit in her name.

Because above all she was a Byron, and for someone so self-absorbed and yet utterly lacking in self-love as her brother that was an irresistible attraction. In the years since their childhoods he had formed some of the most intense friendships of his life, but it was only with a more attractive version of himself, as he now saw Augusta, a woman with so many of the same mannerisms and the same shyness, that he found his deepest, almost platonic desire for completion realised. ‘For thee, my own sweet sister’, he addressed her,

in thy heart

I know myself secure, as thou in mine;

We were and are – I am, even as thou art –

Beings who ne’er each other can resign;

It is the same, together or apart,

From life’s commencement to its slow decline

We are entwined – let death come slow or fast,

The tie which bound the first endures the last!63

With her endless good-humour and sense of fun, her charm and talent for nonsense – her ‘damn’d crinkum-crankum’64 as he called it – Augusta also represented a simple release from the tensions of London life. Almost immediately she became an integral part of his routines, included in his invitations and plans, the novel half of a double-act that was part spontaneous and part calculation. ‘If you like to go with me to ye. Lady Davy’s tonight’, he wrote in a note that nicely captures the blend of pride and vanity with which he looked on her,