Полная версия:

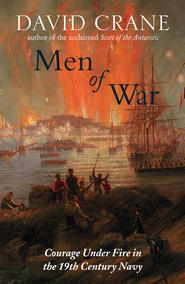

Men of War: The Changing Face of Heroism in the 19th Century Navy

But even if this ‘bigoted’ Hydriot community was a world unto itself – impervious to anything Hastings had to offer, complacently sure of its own superiority, and independent of any central authority – it was still all there was, and at first light on 20 April Hastings and Jarvis sailed over to the desolate Corinth isthmus to present their credentials to Greece’s new president. On their first arrival they were received with a distinctly cautious civility by Mavrocordato, but it was only after further audiences with the Ministers of Marine and War had produced nothing that Hastings learned why. ‘Monsieur le Prince,’ he immediately wrote in protest – and one can hear a certain irony in the use of that title from a descendant of Edward III addressing the heir to a long line of Turkish ‘hired helps’ in the Danubian provinces –

I have determined to take the liberty of addressing your Highness in writing, as I found you occupied when I had the honour of presenting myself at your residence yesterday. I shall speak with freedom, convinced that your Highness will reply in the same manner.

I will not amuse you with recounting the sacrifices I have made to come to serve Greece. I came without being invited, and have no right to complain if my services are not accepted. In that case, I shall only regret that I cannot add my name to those of the liberators of Greece; I shall not cease to wish for the triumph of liberty and civilization over tyranny and barbarism. But I believe that I may say to your Highness without failing in respect, that I have a right to have my services either accepted or refused, for (as you may easily suppose) I can spend my money quite as agreeably elsewhere.

It seems that I am a suspected person because I am an Englishman. Among people without education I expected to meet with some prejudice against Englishmen, in consequence of the conduct of the British government, but I confess that I was not prepared to find such prejudice among men of rank and education. I was far from supposing that the Greek government would believe that every individual in the country adopted the same political opinions. I am the younger son of Sir Charles Hastings, Baronet, general in the army, and in possession of a landed estate of nearly £10,000 a year. The Marquis of Hastings, Governor-General of India, was brought up by my grandfather along with my father, and they have been as brothers. If I were in search of a place I might surely find one more lucrative under the British government in India, and less dangerous as well as more respectable than that of a spy among the Greeks. I venture to say, your Highness, that if the English government wishes to employ a spy here, it would not address a person of my condition, while there are so many strangers in the country who would sell the whole of Greece for a bottle of brandy …

What I demand of your Highness is only to serve, without having the power to injure, your country. What injury can I inflict on Greece, being alone in a ship of war? I must share the fate of the ship, and if it sink I shall be drowned with the rest on board.

Hastings was never to know that Jarvis was behind his cool reception – he had warned Mavrocordato against the help of Perfidious Albion – but the letter had its effect, and on 30 April he at last got permission to sail with the fleet in Tombazis’ corvette, the Themistocles. He recorded his belated introduction to the laissez-faire time-keeping of the Greek navy with characteristic irritation: ‘In the morning we commenced getting under way & hauling out of the harbour. In fifteen years of service I never beheld such a scene. Those of the crew who chose to come on board did so – the rest remained on shore & came off as it suited their convenience.’

If Hastings’s exasperation was understandable, it was hopelessly academic, because by the time the Hydriot fleet finally sailed, they were not just hours but weeks too late to prevent the single greatest tragedy of the whole revolution. The initial object of the fleet was the Greek maritime power base of Psara, but beyond that, just four miles from the Asian mainland, lay another island with a profoundly different tradition and population, whose name over the next months was to become a byword across Europe and America for barbarism and horror.

In the first stages of the uprising, Chios – the peaceable, mastic-growing Shangri La of the Aegean where Occidental fantasy and Eastern reality came as close to being one as they ever have – had done all it could to keep out of a war it could not possibly hope to survive. In the years before the revolt the Turks had left the government of the island more or less completely to its inhabitants, but Ottoman indulgence always came with a bow-string attached, and when in March 1822 the island was reluctantly sucked into the conflict, the Porte responded as only it could. ‘Mercy was out of the question,’ wrote Thomas Gordon, the friend of Hastings and great philhellene historian of the war, ‘the victors butchering indiscriminately all who came in their way; shrieks rent the air, and the streets were strewed with the dead bodies of old men, women and children; even the inmates of the hospital, the madhouse, and the deaf and dumb institution, were inhumanely slaughtered.’

The Turks had landed on 11 April, and less than a month after a slaughter that had left 25,000 dead and slave markets from Constantinople to the Barbary coast glutted with Greek women and boys, all that was left of the old idyll was a wilderness of smouldering villages and unburied corpses. ‘We landed contrary to my opinion,’ Hastings wrote from the Themistocles on 8 May, his impotent anger, as it so often would, recoiling onto the Greek fleet and his fellow volunteers,

for we had no intelligence & … had reason to suppose the Turks were here in numbers … We landed & I wished to establish some order – place a sentinel on the eminence … keep the people together etc but I had to learn what Greeks were. Each man directed his course to the right or left as best pleased him. After rambling about without any object for two hours we reassembled near our boat & when about to embark, four refugees – men – appeared on the eminence above us creeping cautiously towards a wall & some muskets were seen. This was justly calculated to create suspicion. Our men called to us to get into the boat – we did so – all except Jarvis who always pretended to know better than his superiors & those who had seen service … No doubt when Jarvis [the two men had already almost come to a duel] has seen some service he will learn that the duty for an officer is to provide for the protection of his own men as well as the destruction of the enemy. However the confusion I saw reign during this alarm disgusted me with Greek boating – every one commanded – everyone halloed & prepared his musquet & no one took the oars – nobody attempted to get the boat afloat, so the boat was ground fore & aft.

The men on the clifftop turned out to be Greek, but with Hastings and his party finding only three other survivors – two women and a child hiding among the decomposing corpses – revenge was only a matter of time. ‘While I was on board the Admiral,’ he wrote four days later, at sea again in the narrow channel between Chios and mainland Asia,

I beheld a sight which never will be effaced from my memory – A Turkish prisoner was brought on board to be interrogated & after he had answered the questions to him, the crew came and surrounded him, insulting language was first used, the boys were made to pull him by the beard & beat him, he was then dragged several times round the deck by the beard & at length thrown living into the sea. During this horrid ceremony the crew appeared to take the greatest delight in the spectacle, laughing & rejoicing & when he was in the water the man in the boat astern struck him with the boat hook. This sight shocked me so much that I could not help letting them see I disapproved of it: but I was told it was impossible to prevent it & that letting the sailors see my disapproval would be apt to expose me to their revenge.

Mr Anemet a gentleman serving on board the Minerva was on board the Admiral & gave me shocking details of the massacre of the men of a boat they took that morning; after sinking the boat with grape shot they picked up some of the wounded who floated, with two Greek women who were prisoners in the boat & escaped unwounded. The wounded were senseless, but the Greeks did not consider that to kill them at that moment was cruel enough; they therefore revived them & afterwards one of the women with her own hands cut the throats of two of them; the others after torturing greatly, they hung & even heaped their revenge on the bodies. The Turks I was told defended themselves with great courage. The one I saw massacred, uttered no complaint, made no supplication nor acted meanly in any way, true he trembled greatly, but it must be remembered he was surrounded, had already been half drowned & hauled round the deck by the beard; as it was it is not surprising that his nerves should have a little failed him.

‘What marvellous patriotism is to be found in Greece!!!’ Hastings was soon scrawling – the words heavily underlined – on the twenty-fifth, after a rumour reached the ship that the Ottoman fleet were planning an assault on the most remote and exposed of the three Greek naval centres at Psara.

The report … greatly alarmed the men on board our ship, who appeared resolved gallantly to run away & leave their countrymen to have their throats cut in case the attack should take place – quells animaux! … I was sorry to find also that the Franks [i.e. the Western philhellenes] on board the other ships were conducting themselves in a manner not at all likely to gain the esteem of the Greeks, eating, drinking & smoking seemed to be their principal occupations.

All that Hastings asked was the chance to fight, but as the summer dragged on with only a single Greek success to show for it, that seemed as remote as ever. A half-hearted night attack on the Turkish ships under a bright May moon came to nothing, and after a stretch of blockading work off the Turkish-held Nauplia – where Hastings met ‘the famed Baboulina’, revolutionary Greece’s bloodthirsty cross between a Parisian tricôteuse and a vision-free Jeanne d’Arc – he made a final, Cochrane-esque bid to bully Miaulis, the Greek commander, into action. ‘I saw the Admiral this evening,’ he wrote on 6 July, back at Hydra again, where he found himself stranded among the scheming philhellene ‘scum of the earth’ that had made it their home while he had been away with the fleet,

and presented him with a plan for endeavouring to take a frigate – the idea was to direct a fireship & three other vessels upon a frigate during the night & when near the enemy to set fire to certain combustibles which should throw out a great flame; the enemy would naturally conclude they were all fire-ships … However, the admiral returned it to me … without even looking at it or permitting me to explain it to him and I observed a kind of insolent contempt in his manner, which no doubt arose from their late success [an action with a fireship against a Turkish vessel] – for the national character is insolence in success & cowardice in distress. This interview with the admiral disgusted me more than ever with the service – They place you in a position in which it is impossible to render any service, and then they boast (amongst themselves) of their own superiority and the uselessness of the Franks (as they call us).

There was in fact to be one last chance for Hastings, and it came almost before the vitriol in his journal had had time to dry. A couple of days after his rejection by Miaulis the Themistocles again put to sea, and on 15 July was giving chase to a small flotilla of enemy sakolevas south of Tenedos, when a rogue wind took her close in under a cliff heavily manned by Turks. ‘These troops opened a sharp but ill-directed fire of musketry on the deck of the Themistocles,’ George Finlay later wrote – there is, typically, no mention in Hastings’s journal of his own role in the action –

and on this occasion a total want of order, and the disrespect habitually shown to the officers, had very nearly caused the loss of the vessel. The whole crew sought shelter from the Turkish fire under the bulwarks, and no one could be induced to obey the orders which every one issued … Hastings was the only person on deck who remained silently watching the ship slowly drifting towards the rocks. He was fortunately the first to perceive the change in the direction of a light breeze which sprang up, and by immediately springing forward on the bowsprit, he succeeded in getting the ship’s head round. Her sails soon filled, and she moved out of her awkward position. As upwards of two hundred and fifty Turks were assembled on the rocks above, and fresh men were arriving every moment … her destruction seemed inevitable, had she remained an hour within gun-shot of the cliff … Though they had refused to avail themselves of his skill, and neglected his advice, they now showed no jealousy in acknowledging his gallant exploit. Though he treated all with great reserve and coldness, as a means of insuring respect, there was not a man on board that was not ready to do him any service. Indeed the candid and hearty way in which they acknowledged the courage of Hastings, and blamed their own conduct in allowing a stranger to expose his life in so dangerous a manner to save them, afforded unquestionable proof that so much real generosity was inseparable from courage, and that, with proper discipline and good officers, the sailors of the Greek fleet would have had few superiors.

It was something, but not what Hastings had come east to achieve. But then, the Greece that was taking shape while he fretted away the summer on the Themistocles was hardly the country that even the most pragmatic philhellene had hoped for. Little might have happened at sea, but on land it had been a different story. On 16 July a philhellene army under the command of General Normann, a German veteran of the Napoleonic Wars who had fought at Austerlitz on the side of the Austrians, and on the retreat from Moscow with Napoleon, was destroyed at Petta, and with it went the last vestiges of authority remaining to the central government and the Westernised Mavrocordato. From now on the revolution and the new Greece would belong to the victors of Tripolis and a dozen other massacres – to the captains who had reneged on every guarantee of safe conduct they had ever given; who had roasted Jews at the fall of Tripolis, and transposed the severed heads of dogs and women; to the men who could spin out the death of a suspected informant at Nauplia for six days, breaking his fingers, burning out his nails and boiling him alive before smearing his face with honey and burying him up to his neck. It was enough, as one embittered English philhellene put it, to make a volunteer pray for battle, in the hope of seeing the Greeks on his own side killed.

VI

There is no year in the history of the Greek War of Independence so difficult to comprehend as that of 1822. In the first months of the rebellion the Ottoman armies had been too busy with the rebel Albanian Ali Pasha in Ioannina to give the Greeks their full attention, but from the day in early February that Ali’s head was delivered to the Porte and two armies were despatched southwards from their base in Larissa – one down the western side towards Missolonghi, and a second down the east towards Corinth, Nauplia and the Morean heartland of the insurgency – Greece and the Greek revolt looked almost certainly doomed.

The stuttering failure of the western army would not directly involve Hastings, but the collapse of the eastern expedition under the command of Dramali Pasha was another matter. Early in July 1822 Dramali’s army of 23,000 men and 60,000 horses had swept unchecked across the isthmus and on to Argos, but within weeks it had virtually ceased to exist as a fighting force, reduced by starvation, disease, incompetence and unripened fruit to an enfeebled rabble facing the dangers of a humiliating retreat through the passes, crags and narrow gorges of the Dervenakia to the south of Corinth.

The retreat of Dramali’s army was to give the Greeks under Colocotrones – the ruthless scion of a long line of Turk-hating bandit chiefs – their greatest victory of the war, and one that would have been still greater without the lure of the Ottoman baggage trains. With more discipline not a single Turkish soldier could have made it back to Corinth alive; even as it was the bones of Dramali’s troops would litter the mountainsides and gullies for years to come, left to whiten where they had fallen, hacked down in flight or – a tableau mort that titillated the imagination of Edward Trelawny – perched astride the skeletons of their animals, fingers still clenched around the rotting leather of their reins.

The one great prize along the eastern coast still in Ottoman hands at the end of July was the citadel of Nauplia, and that too was only courtesy of their Greek enemy. If the Greek captains had honoured some of their earlier promises the town would have given in long before, but with nothing to hope for from surrender but death or worse, its emaciated garrison – too weak even to man the upper ramparts – had held on even after all hope of rescue was gone, a pitiable testament to the cruelty, ineptitude and greed of their besiegers.

And to their cowardice, Hastings reckoned, because in spite of its towering position, grace and size – partly because of its size – Nauplia’s Palamidi citadel could never have been held by its Turkish garrison against any sustained assault. Hastings had first inspected the fortress from the deck of the Themistocles at the beginning of July, and in the last days before Dramali’s retreat had quitted Hydra with a ‘soi disant’ philhellene frigate captain and incendiary, Count Jourdain, to see if there was any more fighting to be had with the land army than there was with the fleet.

He and Jourdain had sailed to Mili, or ‘the Mills of Lerna’, on the western side of the gulf, and on 27 July were sent across to the tiny island fortress of Bourdzi to reconnoitre the position. ‘We found an irregular old Venetian fortress,’ Hastings noted of the island – the traditional home of the Nauplia executioner in peacetime and a suicidal death-trap to anyone trying to hold it in war –

mounting 13 guns of different calibres & in various conditions – it is entirely commanded by the citadel which could destroy it on any occasion – more particularly as all its heavy guns bear on the entrance of the harbour … The shore on the Northern side of this fort is not distant more than two thirds gun shot, so that the enemy could throw up batteries there which could open a cross fire on this miserable place & destroy it in one day as the walls [are] in a state of decay & the carriages of the guns scarcely able to bear three discharges.

For the next week this dilapidated and useless fortress, floating only a few hundred yards offshore under the guns of the Palamidi fortress, was home for Hastings and a motley crew of Greek and philhellene companions. There seemed no earthly reason why he or anyone else should be asked to hold the position, but there was a streak of masochistic pride about Hastings that served him well under duress, and the more ludicrous the task and the heavier the fire the more determined he was to sit it out ‘while any danger existed’.

The first incoming shots had been so wayward, in fact, that he assumed they were signal guns, but a ‘smart & not badly directed fire’ soon disabused him of that idea. ‘Our guns opened in return,’ he recorded, ‘but want of order obliged us shortly to desist – The men were not stationed at the different batteries so that each went where they pleased & it pleased the greater number to hide themselves.’

With their batteries ill-sited, the gradients sloping in the direction of the recoil, their mortars rusted through, Jourdain’s ‘inflamable balls’ useless, and the carriage wheels broken, this was perhaps no surprise, and one more smart artillery exchange was enough to send the fifty Greeks who had reinforced the fort scuttling for the other side of the gulf. ‘One of the Primates, Bulgari, observed that we were at liberty to quit or remain as we thought proper,’ Hastings recorded that night in his journal, alone now except for four other foreign volunteers equally determined to brave it out, ‘& begged us to consider that we remained by our own choice – We remained though convinced we could do nothing unless we were furnished with means of heating shot red for burning the houses.’

At a severely rationed rate of seven shots an hour, they had shells enough for seven days, but the Turks were under no such restraint and a heavy bombardment over the next two days rendered the fort virtually hors de combat. By 4 August Hastings was concerned enough to send a message across the bay that they risked being cut off, and two days later, to the distant sounds from the Dervenakia of the slaughter of Dramali’s army, he finally decided that they had done enough. ‘The reiterated insults I had received made it painful to a degree to remain,’ he wrote from the Mills after their escape in a Greek vessel,

& I should have left the place long ago, had the fire not been so continually kept up on the place. At 4 therefore I quitted the fort with the other gentlemen & proceeded alongside the Schooner but here they would not allow us to approach, however being highly outraged I seized a favourable opportunity & jumping from the boat seized the chain plates of the Schooner & mounted on deck – there I preferred my complaint to the Members of the Govt on board, they replied as usual with a shrug of the shoulders saying ‘what can you expect from people without education!!’

As Greece slid inexorably into chaos, with Colocotrones in the Morea and Odysseus Androutses, the most formidable and devious of the klephts, in mainland Roumeli, rampantly out of control, the next twelve months were as bleakly pointless as any in Hastings’s life. After five fruitless days at the Mills he had decided that he could be better employed on Hydra, but within the week he was again back on land, crossing and recrossing the Morea in a restless search for a leader who might impose some structure on the enveloping turmoil. ‘I was glad to find that Colocotroni’ – the ‘hero’ of Tripolis and the Dervenakia – ‘was disposed to make a beginning towards introducing a little regularity,’ he wrote on 5 October, in Tripolis in time to witness the town en fête for the grotesque anniversary celebrations of the horrors of 1821, ‘& I find that having been Major of the Greek corps in the English service [in the Ionian Isles], he is able to appreciate the advantages resulting from regular discipline … After mass we visited him, he appeared extremely acute & intelligent & perhaps (not withstanding the character which the Govt give him) is better able to govern than they are – the abuse heaped upon him by the Hydriots evidently arises from jealousy of his influence & success.’

For a good English Whig Hastings was perhaps becoming more tolerant of despotism and ‘strong government’ than was good for him, but then again a journey through the parched and devastated Morea in the autumn of 1822 was not going to provide a lesson in the virtues of constitutional government. After leaving Tripolis and Colocotrones he made his way south-west to Navarino and Messina, filling his journal as he went with anything and everything from the number of trees in Arcadia (28,000) to the sight of a Kalamata beggar – amputated feet in hands as he crawled through the marketplace – or the latest example of Greek perfidy. ‘The Turks had obtained terms of capitulation,’ he recorded of the surrender of Navarino’s Turkish garrison,

by which it was stipulated that the lives of the garrison should be spared, that they should be permitted to carry away 1/3 of their property & be transferred to Asia on board Neutral Vessels – But no sooner had the Greeks taken possession of the Fortress than they massacred the greatest number of the inhabitants & transported the rest to a rock in the harbour where they were starved to death … It is confidently asserted that the bishop issued his malediction on those Greeks who failed to massacre the Turks.