Полная версия

Полная версияGreater Britain

Savages though they be, in irregular warfare we are not their match. At the end of 1865, we had of regulars and militia seventeen thousand men under arms in the North Island of New Zealand, including no less than twelve regiments of the line at their “war strength,” and yet our generals were despondent as to their chance of finally defeating the warriors of a people which – men, women, and children – numbered but thirty thousand souls.

Men have sought far and wide for the reasons which led to our defeats in the New Zealand wars. We were defeated by the Maories, as the Austrians by the Prussians, and the French by the English in old times – because the victors were the better men. Not the braver men, when both sides were brave alike; not the stronger; not, perhaps, taking the average of our officers and men, the more intelligent; but capable of quicker movement, able to subsist on less, more crafty, more skilled in the thousand tactics of the bush. Aided by their women, who, when need was, themselves would lead the charge, and who at all times dug their fern-root and caught their fish; marching where our regiments could not follow, they had, as have the Indians in America, the choice of time and place for their attacks, and while we were crawling about our military roads upon the coast, incapable of traversing a mile of bush, the Maories moved securely and secretly from one end to the other of the island. Arms they had, ammunition they could steal, and blockade was useless with enemies who live on fern-root. When they found that we burnt their pahs, they ceased to build them; that was all. When we brought up howitzers, they went where no howitzers could follow. It should not be hard even for our pride to allow that such enemies were, man for man, in their own lands our betters.

All nations fond of horses, it has been said, flourish and succeed. The Maories love horses and ride well. All races that delight in sea are equally certain to prosper, empirical philosophers will tell us. The Maories own ships by the score, and serve as sailors whenever they get a chance: as deep-sea fishermen they have no equals. Their fondness for draughts shows mathematical capacity; in truthfulness they possess the first of virtues. They are shrewd, thrifty; devoted friends, brave men. With all this, they die.

“Can you stay the surf which beats on Wanganui shore?” say the Maories of our progress; and, of themselves: “We are gone – like the moa.”

CHAPTER VI.

THE TWO FLIES

“As the Pakéha fly has driven out the Maori fly;As the Pakéha grass has killed the Maori grass;As the Pakéha rat has slain the Maori rat;As the Pakéha clover has starved the Maori fern,So will the Pakéha destroy the Maori.”THESE are the mournful words of a well-known Maori song.

That the English daisy, the white clover, the common thistle, the chamomile, the oat, should make their way rapidly in New Zealand, and put down the native plants, is in no way strange. If the Maori grasses that have till lately held undisturbed possession of the New Zealand soil, require for their nourishment the substances A, B, and C, while the English clover needs A, B, and D; from the nature of things A and B will be the coarser earths or salts, existing in larger quantities, not easily losing vigor and nourishing force, and recruiting their energies from the decay of the very plant that feeds on them; but C and D will be the more ethereal, the more easily destroyed or wasted substances. The Maori grass, having sucked nearly the whole of C from the soil, is in a weakly state, when in comes the English plant, and, finding an abundant store of untouched D, thrives accordingly, and crushes down the Maori.

The positions of flies and grasses, of plants and insects, are, however, not the same. Adapted by nature to the infinite variety of soils and climates, there are an infinite number of different plants and animals; but whereas the plant depends upon both soil and climate, the animal depends chiefly upon climate, and little upon soil – except so far as his home or his food themselves depend on soil. Now, while soil wears out, climate does not. The climate in the long run remains the same, but certain apparently trifling constituents of the soil will wholly disappear. The result of this is, that while pigs may continue to thrive in New Zealand forever and a day, Dutch clover (without manure) will only last a given and calculable time.

The case of the flies is plain enough. The Maori and the English fly live on the same food, and require about the same amount of warmth and moisture: the one which is best fitted to the common conditions will gain the day, and drive out the other. The English fly has had to contend not only against other English flies, but against every fly of temperate climates: we having traded with every land, and brought the flies of every clime to England. The English fly is the best possible fly of the whole world, and will naturally beat down and exterminate, or else starve out, the merely provincial Maori fly. If a great singer – to find whom for the London stage the world has been ransacked – should be led by the foible of the moment to sing for gain in an unknown village, where on the same night a rustic tenor was attempting to sing his best, the London tenor would send the provincial supperless to bed. So it is with the English and Maori fly.

Natural selection is being conducted by nature in New Zealand on a grander scale than any we have contemplated, for the object of it here is man. In America, in Australia, the white man shoots or poisons his red or black fellow, and exterminates him through the workings of superior knowledge; but in New Zealand it is peacefully, and without extraordinary advantages, that the Pakéha beats his Maori brother.

That which is true of our animal and vegetable productions is true also of our man. The English fly, grass, and man, they and their progenitors before them, have had to fight for life against their fellows. The Englishman, bringing into his country from the parts to which he trades all manner of men, of grass seeds, and of insect germs, has filled his land with every kind of living thing to which his soil or climate will afford support. Both old inhabitants and interlopers have to maintain a struggle which at once crushes and starves out of life every weakly plant, man, or insect, and fortifies the race by continual buffetings. The plants of civilized man are generally those which will grow best in the greatest variety of soils and climates; but in any case, the English fauna and flora are peculiarly fitted to succeed at our antipodes, because the climates of Great Britain and New Zealand are almost the same, and our men, flies, and plants – the “pick” of the whole world – have not even to encounter the difficulties of acclimatization in their struggle against the weaker growths indigenous to the soil.

Nature‘s work in New Zealand is not the same as that which she is quickly doing in North America, in Tasmania, in Queensland. It is not merely that a hunting and fighting people is being replaced by an agricultural and pastoral people, and must farm or die: the Maori does farm; Maori chiefs own villages, build houses, which they let to European settlers; we have here Maori sheep-farmers, Maori ship-owners, Maori mechanics, Maori soldiers, Maori rough-riders, Maori sailors, and even Maori traders. There is nothing which the average Englishman can do which the average Maori cannot be taught to do as cheaply and as well. Nevertheless, the race dies out. The Red Indian dies because he cannot farm; the Maori farms, and dies.

There are certain special features about this advance of the birds, beasts, and men of Western civilization. When the first white man landed in New Zealand, all the native quadrupeds save one, and nearly all the birds and river-fishes, were extinct, though we have their bones, and traditions of their existence. The Maories themselves were dying out. The moa and dinoris were both gone; there were few insects, and no reptiles. “The birds die because the Maories, their companions, die,” is the native saying. Yet the climate is singularly good, and food for beast and bird so plentiful that Captain Cook‘s pigs have planted colonies of “wild boars” in every part of the islands, and English pheasants have no sooner been imported than they have commenced to swarm in every jungle. Even the Pakéha flea has come over in the ships, and wonderfully has he thriven.

The terrible want of food for men that formerly characterized New Zealand has had its effects upon the habits of the Maori race. Australia has no native fruit trees worthy cultivation, although in the whole world there is no such climate and soil for fruits; still, Australia has kangaroos and other quadrupeds. The Ladrones were destitute of quadrupeds, and of birds, except the turtle-dove; but in the warm damp climate fruits grew, sufficient to support in comfort a dense population. In New Zealand the windy cold of the winters causes a need for something of a tougher fiber than the banana or the fern-root. There being no native beasts, the want was supplied by human flesh, and war, furnishing at once food and the excitement which the chase supplies to peoples that have animals to hunt, became the occupation of the Maories. Hence in some degree the depopulation of the land; but other causes exist, by the side of which cannibalism is as nothing.

The British government has been less guilty than is commonly believed as regards the destruction of the Maories. Since the original misdeed of the annexation of the isles, we have done the Maories no serious wrong. We recognized the claim of a handful of natives to the soil of a country as large as Great Britain, of not one-hundredth part of which had they ever made the smallest use; and, disregarding the fact that our occupation of the coast was the very event that gave the land its value, we have insisted on buying every acre from the tribe. Allowing title by conquest to the Ngatiraukawa, as I saw at Parewanui Pah, we refuse to claim even the lands we conquered from the “Kingites.”

The Maories have always been a village people, tilling a little land round their pahs, but incapable of making any use of the great pastures and wheat countries which they “own.” Had we at first constituted native reserves, on the American system, we might, without any fighting, and without any more rapid destruction of the natives than that which is taking place, have gradually cleared and brought into the market nearly the whole country, which now has to be purchased at enormous prices, and at the continual risk of war.

As it is, the record of our dealings with the Queen‘s native subjects in New Zealand has been almost free from stain, but if we have not committed crimes, we have certainly not failed to blunder: our treatment of William Thompson was at the best a grave mistake. If ever there lived a patriot he was one, and through him we might have ruled in peace the Maori race. Instead of receiving the simplest courtesy from a people which in India showers honors upon its puppet kings and rajahs, he underwent fresh insults each time that he entered an English town or met a white magistrate or subaltern, and he died, while I was in the colonies – according to Pakéha physicians, of liver complaint; according to the Maories, of a broken heart.

At Parewanui and Otaki, I remarked that the half-breeds are fine fellows, possessed of much of the nobility of both the ancestral races, while the women are famed for grace and loveliness. In miscegenation it would have seemed that there was a chance for the Maori, who, if destined to die, would at least have left many of his best features of body and mind to live in the mixed race, but here comes in the prejudice of blood, with which we have already met in the case of the negroes and Chinese. Morality has so far gained ground as greatly to check the spread of permanent illegitimate connections with native women, while pride prevents intermarriage. The numbers of the half-breeds are not upon the increase: a few fresh marriages supply the vacancies that come of death, but there is no progress, no sign of the creation of a vigorous mixed race. There is something more in this than foolish pride, however; there is a secret at the bottom at once of the cessation of mixed marriages and of the dwindling of the pure Maori race, and it is the utter viciousness of the native girls. The universal unchastity of the unmarried women, “Christian” as well as heathen, would be sufficient to destroy a race of gods. The story of the Maories is that of the Tahitians, and is written in the decorations of every gate-post or rafter in their pahs.

We are more distressed at the present and future of the Maories than they are themselves. For all our greatness, we pity not the Maories more profoundly than they do us when, ascribing our morality to calculation, they bask in the sunlight, and are happy in their gracelessness. After all, virtue and arithmetic come from one Greek root.

CHAPTER VII.

THE PACIFIC

CLOSELY resembling Great Britain in situation, size, and climate, New Zealand is often styled by the colonists “The Britain of the South,” and many affect to believe that her future is destined to be as brilliant as has been the past of her mother country. With the exaggeration of phrase to which the English New Zealanders are prone, they prophesy a marvelous hereafter for the whole Pacific, in which New Zealand, as the carrying and manufacturing country, is to play the foremost part, the Australias following obediently in her train.

Even if the differences of Separatists, Provincialists, and Centralists should be healed, the future prosperity of New Zealand is by no means secure. Her gold yield is only about a fifth of that of California or Victoria. Her area is not sufficient to make her powerful as an agricultural or pastoral country, unless she comes to attract manufactures and carrying trade from afar, and the prospect of New Zealand succeeding in this effort is but small. Her rivers are almost useless for manufacturing purposes owing to their floods; the timber supply of all her forests is not equal to that of a single county in the State of Oregon; her coal is inferior in quality to that of Vancouver Island, in quantity to that of Chili, in both respects to that of New South Wales. The harbors of New Zealand are upon the eastern coasts, but the coal is chiefly upon the other side, where the river bars make trade impossible.

The coal that has been found at the Bay of Islands is said to be plentiful and of good quality, and may be made largely available for steamers on the coast; the steel sand of Taranaki, smelted by the use of petroleum, also found within the province, may become of value; her own wool, too, New Zealand will doubtless one day manufacture into cloth and blankets; but these are comparatively trifling matters: New Zealand may become rich and populous without being the great power of the Pacific, or even of the South.

The climate of the North Island is winterless, moist, and warm, and its effects are already seen in a certain want of enterprise shown by the government and settlers. I remarked that the mail steamers which leave Wellington almost everyday are invariably “detained for dispatches:” it looks as though the officers of the colonial or imperial government commence to write their letters only when the hour for the sailing of the ship has come. An Englishman visiting New Zealand was asked in my presence how long his business at Wanganui would keep him in the town. His answer was: “In London it would take me half an hour; so I suppose about a week – about a week!”

In Java, and the other islands of the Indian archipelago, we find examples of the effect of the supineness of dwellers in the tropics upon the economic position of their countries. Many of the Indian isles possess both coal and cheap labor, but have failed to become manufacturing communities on a large scale only because the natives have not the energy requisite for the direction of factories and workshops, while European foremen have to be paid enormous wages, and, losing their spirit in the damp, unchanging climate of the islands, soon become more indolent than the natives.

The position of the various stores of coal in the Pacific is of extreme importance as an index to the future distribution of power in that portion of the world; but it is not enough to know where coal is to be found without looking also to the quantity, quality, cheapness of labor, and facility for transport. In China (in the Si Shan district) and in Borneo, there are extensive coal fields, but they lie “the wrong way” for trade. On the other hand, the Californian coal – at Monte Diablo, San Diego, and Monterey – lies well, but is bad in quality. The Talcahuano bed in Chili is not good enough for ocean steamers, but might be made use of for manufactures, although Chili has but little iron. Tasmania has good coal, but in no great quantity, and the beds nearest to the coast are formed of inferior anthracite. The three countries of the Pacific which must, for a time at least, rise to manufacturing greatness, are Japan, Vancouver Island, and New South Wales, but which of these will become wealthiest and most powerful depends mainly on the amount of coal which they respectively possess so situated as to be cheaply raised. The dearness of labor under which Vancouver suffers will be removed by the opening of the Pacific Railroad, but for the present New South Wales has the cheaper labor; and upon her shores at Newcastle are abundant stores of a coal of good quality for manufacturing purposes, although for sea use it burns “dirtily,” and too fast, the colony possesses also ample beds of iron, copper, and lead. Japan, as far as can be at present seen, stands before Vancouver and New South Wales in almost every point: she has cheap labor, good climate, excellent harbors, and abundant coal; cotton can be grown upon her soil, and this, and that of Queensland, she can manufacture and export to America and to the East. Wool from California and from the Australias might be carried to her to be worked, and her rise to commercial greatness has already commenced with the passage of a law allowing Japanese workmen to take service with European capitalists in the “treaty-ports.” Whether Japan or New South Wales is destined to become the great wool-manufacturing country, it is certain that fleeces will not long continue to be sent half round the world – from Australia to England – to be worked, and then round the other half back from England to Australia, to be sold as blankets.

The future of the Pacific shores is inevitably brilliant; but it is not New Zealand, the center of the water hemisphere, which will occupy the position that England has taken in the Atlantic, but some country such as Japan or Vancouver, jutting out into the ocean from Asia or from America, as England juts out from Europe. If New South Wales usurps the position, it will be not from her geographical situation, but from the manufacturing advantages she gains by the possession of vast mineral wealth.

The political power of America in the Pacific appears predominant: the Sandwich Islands are all but annexed, Japan all but ruled by her, while the occupation of British Columbia is but a matter of time, and a Mormon descent upon the Marquesas is already planned. The relations of America and Australia will be the key to the future of the South.

…On the 26th of December I left New Zealand for Australia.

APPENDIX.

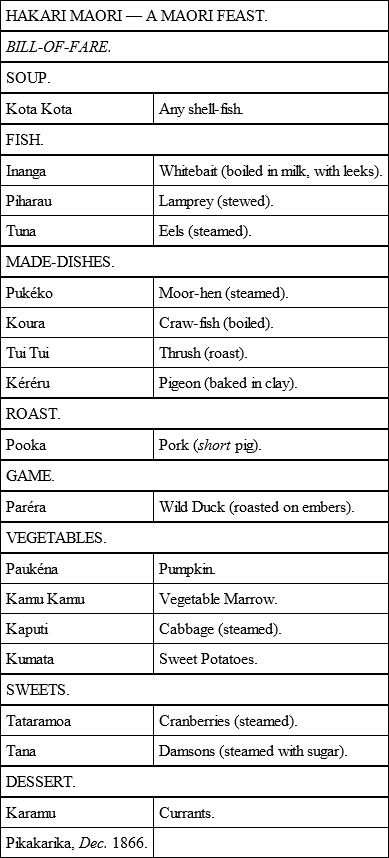

A MAORI DINNER

FOR those who would make trial of Maori dishes, here is a native bill-of-fare, such as can be imitated in the South of England:

PART III.

AUSTRALIA

CHAPTER I.

SYDNEY

AT early light on Christmas-day, I put off from shore in one of those squalls for which Port Nicholson, the harbor of Wellington, is famed. A boat which started from the ship at the same time as mine from the land, was upset, but in such shallow water that the passengers were saved, though they lost a portion of their baggage. As we flew toward the mail steamer, the Kaikoura, the harbor was one vast sheet of foam, and columns of spray were being whirled in the air, and borne away far inland upon the gale. We had placed at the helm a post-office clerk, who said that he could steer, but, as we reached the steamer‘s side, instead of luffing-up, he suddenly put the helm hard a-weather, and we shot astern of her, running violently before the wind, although our treble-reefed sail was by this time altogether down. A rope was thrown us from a coal hulk, and, catching it, we were soon on board, and spent our Christmas walking up and down her deck on the slippery black dust, and watching the effects of the gale. After some hours the wind moderated, and I reached the Kaikoura just before she sailed. While we were steaming out of the harbor through the boil of waters that marks the position of the submarine crater, I found that there was but one other passenger for Australia to share with me the services of ten officers and ninety men, and the accommodations of a ship of 1500 tons. “Serious preparations and a large ship for a mere voyage from one Australasian colony to another,” I felt inclined to say, but during the voyage and my first week in New South Wales I began to discover that in England we are given over to a singular delusion as to the connection of New Zealand and Australia.

Australasia is a term much used at home to express the whole of our Antipodean possessions; in the colonies themselves the name is almost unknown, or, if used, is meant to embrace Australia and Tasmania, not Australia and New Zealand. The only reference to New Zealand, except in the way of foreign news, that I ever found in an Australian paper, was a congratulatory paragraph on the amount of the New Zealand debt; the only allusion to Australia that I ever detected in the Wellington Independent was in a glance at the future of the colony, in which the editor predicted the advent of a time when New Zealand would be a great naval nation, and her fleet engaged in bombarding Melbourne, or levying a contribution upon Sydney.

New Zealand, though a change for the better is at hand, has hitherto been mainly an aristocratic country; New South Wales and Victoria mainly democratic. Had Australia and New Zealand been close together, instead of as far apart as Africa and South America, there could have been no political connection between them so long as the traditions of their first settlement endured.

Not only is the name “Australasia” politically meaningless, but geographically incorrect, for New Zealand and Australia are as completely separated from each other as Great Britain and Massachusetts. No promontory of Australia runs out to within 1000 miles of any New Zealand cape; the distance between Sydney and Wellington is 1400 miles; from Sydney to Auckland about the same. The distance from the nearest point of New Zealand of Tasman‘s peninsula, which itself projects somewhat from Tasmania, is greater than that of London from Algiers: from Wellington to Sydney, opposite ports, is as far as from Manchester to Iceland, or from Africa to Brazil.

The sea that lies between the two great countries of the south is not, like the Central or North Pacific, a sea bridged with islands, ruffled with trade winds, favorable to sailing ships, or overspread with a calm that permits the presence of light-draught paddle steamers. The seas which separate Australia from New Zealand are cold, bottomless, without islands, torn by Arctic currents, swept by polar gales, and traversed in all weathers by a mountainous swell. After the gale of Christmas-day we were blessed with a continuance of light breezes on our way to Sydney, but never did we escape the long rolling hills of seas that seemed to surge up from the Antarctic pole: our screw was as often out of as in the water; and in a fast new ship we could scarcely average nine knots an hour throughout the day. The ship which had brought the last Australian mail to Wellington before we sailed was struck by a sea which swept her from stem to stern, and filled her cabin two feet deep, and this in December, which here is midsummer, and answers to our July. Not only is the intervening ocean wide and cold, but New Zealand presents to Australia a rugged coast guarded by reefs and bars, and backed by a snowy range, while she turns toward Polynesia and America all her ports and bays.