Полная версия:

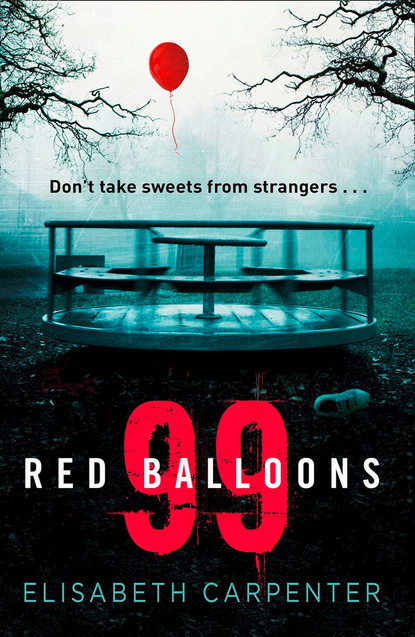

99 Red Balloons

Emma gets up quickly, glass in hand, and sways slightly. She collapses in front of the television, landing on her knees.

Mum sits forward on her chair, but doesn’t get up.

‘Emma. Are you okay? Have you drunk too much?’

I look at Mum through narrow eyes. What goes on in her head? Emma can drink as much as she wants; she doesn’t need policing right now.

‘I’ve got to find that DVD,’ says Emma.

When I get up I feel dizzy. My glass clinks on the mantelpiece as I place it between the photographs of Dad and the one of Grace and Jamie last Christmas – their faces covered in pudding and cream after they’d pretended to be cats, eating from a saucer on the floor.

I kneel down next to Emma and flick through the DVD cases in the drawer under the television.

‘The one from last year,’ she says, but I know which one – it’s the only one they had transferred to DVD from Matt’s phone. We both have a copy. I thank God that Jamie is upstairs, so he doesn’t have to see everyone like this.

‘What are you doing, Emma?’ Mum gets up and stands behind us. ‘You’re just torturing yourself.’

I can tell without looking that she’s got her hands on her hips. Three sighs later, she leaves the room and stomps upstairs.

‘Here it is.’

Emma wrestles the case open and opens the disc tray of Grace’s Xbox. She doesn’t move from the floor as the video of Christmas past takes over the television. The camera travels from the Christmas tree to the door to the hallway. Grace appears in her pyjamas, with strands of her shoulder-length hair in a golden halo around her head.

‘You haven’t started without me, have you?’ she says.

‘Course we haven’t, sleepyhead.’ Matt’s voice booms through the speakers.

Grace walks over to the tree, which has at least fifty presents underneath it. She stands with her back to the camera, putting both hands on her head.

‘He actually came!’ She turns round, her eyes glistening. ‘I told Hannah he was real and she didn’t believe me, Daddy.’

The camera turns to the floor while her little feet run to Matt and she jumps onto his lap. The screen goes black for a couple of seconds before Grace is pictured sitting cross-legged on the carpet, yanking open a present wrapped with too much Sellotape.

‘What is it?’ It’s Emma – the camera pans to her at the kitchen doorway, looking flushed and wearing an apron covered with smears of food.

‘Socks,’ shouts Grace off camera.

Emma rolls her eyes, turns round and walks into the kitchen.

The camera goes back to Grace, holding up the socks.

‘They’re Minions! I love them!’

She rips off the cardboard and puts them on. She stomps in a circle.

‘I’m trampling all over my Minions,’ she says, laughing.

Next to me, Emma grabs the Xbox controller and presses pause. It leaves Grace with one foot in mid-air and a huge smile on her lovely face. My hands are soaking wet and I realise that my tears have been dripping onto them.

Emma throws the controller onto the floor. I take the glass of wine from her hands just in time as she buries her face in them.

‘Why didn’t I watch her open her presents? I only saw her open the Xbox and that was it.’ She sobs into her sleeve. ‘I’m a terrible mother. I don’t deserve her.’

I rub her back. It doesn’t feel enough. I want to magic Grace from where she is now and back into this room. My heart hurts.

‘But you had the dinner to cook for everyone,’ I say. ‘She loves your roast potatoes.’

It’s such a shit thing to say. It makes her cry even more.

‘When she comes back,’ she says, ‘I’ll make them for her every day.’

Her cries are so loud and so heartbreaking. I pull her towards me and we cry together.

Mum is upstairs comforting Emma. Jamie went to sleep an hour ago and Matt’s sitting on the sofa, his head resting on the back, his eyes looking to the ceiling. I step over his outstretched legs and sit next to him. I lean back into the sofa, feeling a brief flutter of comfort from the soft cushions around me. It’s so quiet that the ticking clock is the only sound.

The times I have been here, when Grace has been watching the Disney channel, playing her dance game on the console or getting cross with Minecraft— stop, stop. Don’t think about it. I can’t go under too, not when they need me.

I wipe my face with both of my sleeves and try to muffle my sniffs with the tissues constantly balled up in my hand. I don’t know what to say to Matt. He brings his head down.

‘About that text,’ he says. ‘The emails …’

‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘I don’t want you to think that that was all I thought about when the police took the laptop – that I wasn’t thinking about Grace. It’s just that I’d been at work and—’

‘I know. Don’t give it a second thought.’

‘I’m sorry about shouting at you before.’ He breathes in, and his chest rises. He turns his head towards mine. ‘We shouldn’t have started all of that anyway.’

I say nothing in return, but my face flushes.

‘I’d been at work,’ he repeats. ‘While Grace was being taken, or hurt, or God-knows-what – and for what? I work so hard for us, for our little family – and when it counted, I wasn’t even here for them.’

Emma and Matt’s lives are so far removed from mine. Jamie’s father sees him every Saturday night and Sunday, yet my son is never included in Neil and his new wife’s holidays. They put on expensive birthday parties that always put my homemade meal and birthday cake to shame. They invited Jamie for Chrismas the year before last and gave him at least thirty presents. I spent that Christmas with Mum. Jamie worried about me, but I couldn’t show how I really felt – I had to be happy for him being surrounded by Neil and Joanna’s families. It’s something Emma and I never had – a big family gathering. It’s something Jamie deserves.

Tears spring to my eyes again. Everything’s making me cry. I’m being over-sentimental. I wish I could be someone else sometimes.

Matt turns his head towards mine again. This time I turn and face him.

‘You’re always here, aren’t you?’ he says.

I frown.

‘I don’t mean that in a bad way. I mean, you’re always there for us. You work, you have Jamie. I don’t know how you do it on your own. You’re so strong.’ He reaches out his hand. With his index finger he strokes my cheek. ‘So strong.’

I sit there for a few seconds. Feeling the warmth of his hand near my face. What must it be like to have that all the time, to have someone close to you with affection at the flick of a finger?

I gently move his finger away with my hand.

‘I’m not as strong as you think.’

He brings his hand down and folds his arms.

‘Emma’s so cold.’

I don’t know where to look. My cheeks are on fire. Emma hasn’t mentioned any problems between them, but then she hasn’t said much about anything for the past few weeks.

‘Shit,’ says Matt. ‘I don’t mean now. I mean before. Before Grace.’ He leans forward and rests his forehead in his hands. ‘What the fuck am I talking about? I’m so sorry, Steph. You always bear the brunt of my shit. Why am I even thinking about it, let alone saying it?’

I’ve known Matt longer than I have my ex-husband. It’s only since last Christmas that I became nervous around him.

We were sitting next to each other at the table. Emma was flitting about, appearing busy when all the food was already laid out. I was wearing the red dress I’d worn to my work’s Christmas party, and had my hair cut shorter so it rested on my shoulders.

‘You’re looking great today, Steph,’ he said, smiling at me. ‘I think being single suits you.’

He’d never commented on my looks before. It was such a harmless remark, but it surprised me so much that I didn’t reply and my face burned. I was relieved when Emma finally sat down, but from that moment, whenever he talked to me, it was as though there was no one else in the room.

I don’t think Emma noticed – she always seemed so preoccupied with other things. I can barely glance at him now when others are around us, in case they guess how I feel.

When I first told Emma that Neil had left, she came round to my house straight away, dragging Matt with her. When she went upstairs to talk to Jamie, Matt sat on the chair by the window – the one Neil usually sat in.

Matt looked around the living room – at the bits and pieces Neil and I had bought over the years; the mantelpiece that gave the impression of a happy marriage – the wedding photograph, the candles, that stupid figurine of a couple dancing that Neil’s mother bought.

Matt clasped his hands together; he looked awkward, as though he didn’t know what to say to me. He hardly ever visited my house, I was always the one going there. He didn’t suit sitting in it.

‘I don’t know the details, Steph,’ he said. ‘But I’m so sorry.’

‘Did Neil say anything to you about it?’

‘God no! To be honest we don’t really talk outside of family gatherings. I don’t think he likes me that much.’

He was right. Neil never had anything good to say about Matt. ‘Full of himself; I’m sure he’s going a bit thin on top; putting on a bit of weight is our Matt.’ Neil could be a right bitch. I wrote it off as harmless jealousy at the time; he was nice to Matt’s face – overly so, to the point that it appeared a little obsequious. Neil hadn’t attended the last few family meals; he was always working on some important project. I should’ve noticed him quietly removing himself from my family.

‘I’m here for you, Steph,’ said Matt. ‘Anytime you need to talk.’

It was strange hearing him say I. Whenever Emma and Matt usually spoke it was as a collective: ‘We’re getting this for Grace’; ‘Are you coming round to ours?’ Neil and I never talked like that.

I lean forward and look at him now – this man I have known for as long as Emma has. When I think about it, Emma had been rather distracted – she does that sometimes when she’s having a hard time at work and doesn’t want to bother anyone with her troubles. ‘Everyone has better things to think about than my problems,’ she always says, but she doesn’t mean it. Perhaps she includes Matt in everyone.

My hand reaches over to him; it hovers for a few seconds before I pat his back. I can’t do anything else.

Chapter Fourteen

The only words I’ve said to George since the ferry are yes, no and thank you. And we’ve been driving for over a hundred hours or whatever it is. I’m usually a chatterbox in the car – Mummy would have told me to keep it zipped at least twenty times if she were driving me. My bum is burning I’ve been sitting on it for that long.

‘Come on, kid.’ He keeps trying to talk to me. ‘I’m getting bored driving, listening to bloody French radio stations. You’re not still mad at me, are you?’

He was mad at me, but I can’t say that. He’d tell me off again. He can just turn. I’ve seen grown-ups do that. I keep trying to guess to myself how old he is. He’s older than Daddy, but not as old as Gran. His hair is black, but it has loads of streaks of grey, and he’s either got a lot of hair gel in it, or it needs washing. That’s what Mummy says about Daddy’s, though he doesn’t wear hair gel much these days.

Tears come to my eyes when I think of Mummy and Daddy. They’ll be missing me by now. Are they really waiting for me in Belgium? George won’t let me talk to them on the phone. It would be good to hear their voices, then I won’t miss them as much.

I have to blink really fast to stop the tears. I daren’t ask George about Mummy any more. Every time I do, he shouts at me. For the fiftieth fucking time, stop talking about Mummy and Daddy. I’ll leave you in a field if you’re not careful. It was dark when he said that.

Out of the window, the land is flat. It’s like I can see for miles, but I can’t see England. We’re nowhere near the sea.

‘When are we stopping for food?’ It’s my tummy that told my mouth to talk. My brain didn’t want it to.

‘Ah, so it does speak.’ He reaches over to the passenger seat and puts a cap on his head. It’s not a nice cap like Abigail from school got from Disneyland, but a beige one – like a grandad would wear. ‘Once we cross the border, we’ll stop off somewhere. Promise. We just have to get past these bastards.’

He’s the only man I’ve ever met that would do swearing in front of a kid. My gran would have a coronary if she heard him.

In front of us, cars are lined up in rows. There are little houses in the middle of the road that everyone is stopping beside. George turns round.

‘Listen, kid. They might call you by a different name, but it’s just a game. We’re playing at pretend. If you win, and they don’t guess your real name, then I’ll buy you some sweets after your dinner. Deal?’

I nod. I just heard different name and sweets. I’m quite good at pretending. In my first school play, I was Mary – and I didn’t have to say anything. All the grown-ups believed I actually was Mary. ‘George’ might not even be his real name; I said it twice ten minutes ago and he didn’t reply. He was probably ignoring me again.

He can’t sit still in his seat. He must have ants in his pants. He turns round again.

‘Are you all right? Just be calm, everything will be okay.’

I am calm.

He wiggles his fingers on the steering wheel.

‘Come on, man. You can do it. Ten grand, ten grand. All the booze I can drink. Come on, man.’

He thinks he’s whispering, but he’s not doing it properly.

The car stops. George winds down the window, and says something. It’s not English.

He hands them some paper, but I can’t see what’s on it. He told me to look out of my side, so I can’t peek too much.

A face appears at the window. A man with a grey beard. He’s wearing a flat hat, like a policeman’s. He points at me and makes circle shapes with his hand. It makes me laugh.

‘He’s telling you to wind the window down.’ George doesn’t sound mad, or happy.

I grab the handle with two hands and wind it round until the window is halfway down. The man squints at me. He’s really close, but his nose doesn’t come through the window. Is he a policeman? Shall I tell him that I’ve lost my mummy? I wish I knew how to speak the way George does. I’m trying to smile but my eyes are watering.

He stands back up and walks slowly round the car. He bends down to talk to George.

‘Die Kind ist acht?’

He’s talking like they sing in that song. I wish I knew more words than ninety-nine red balloons.

‘Ja weiß ich,’ says George. ‘Wir hören dass die ganze Zeit. Das arme Kind ist klein für ihr Alter.’

The man in the uniform laughs, but I can’t hear what he says back. I wouldn’t be able to understand it anyway. The guard hits the top of the car twice and says, ‘Willkommen zurück nach Deutschland.’ And we drive away.

After three minutes, George flings off his cap. He bangs the steering wheel three times with his fists. ‘Get the hell in! We did it, kid. That was the worst one – they’re right tough sods, those German border bastards. We’ve only gone and fucking done it. We’re in Germany, little one!’

Germany? My mummy’s never been to Germany before. Why would she be here?

I look out of the window, and it’s raining.

So are my eyes.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов